By Jason M. Barr October 7, 2017

What was the world’s first skyscraper? If you do have an answer, you would be, most assuredly, wrong (sorry). Any skyscraper that we claim as the “first” is merely a convenience—a social convention to provide a simple answer to a complicated question.

But why would it be wrong? For two reasons. First, there is no universal definition of a skyscraper. Is it a relatively tall building, or a building that rises above some threshold (say 80, 90, or 100 meters), or perhaps both?

Alternatively, is it based on the materials and technology used? This definition leads to the second problem. After the Civil War, there were many buildings that incorporated some innovation, and thus we can point to any one of those structures to suggest it was the Original Skyscraper.

The most popular answer is that the ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, completed in 1885, was the first true skyscraper. Why? Because the belief is that it was the one—the iphone of real estate—that fundamentally altered the world by applying the currently-available technology in a new way.

Most significant is that the architect, William Le Baron Jenney, had the key insight to use iron (later replaced by steel) framing. Previously, large buildings used the walls to bear the load of the structure. But as the need for taller buildings arose in the late-19th century, this approach was no longer practical. The higher the building went, the thicker would be the walls on the lower floors, eating into the rentable space and rendering the project unprofitable.

However, in some sense, Jenney’s structure was a prototype, since the iron beams were embedded in the masonry walls, which also helped carry the load. Later buildings would use pure steel frames, or skeletons, while the walls were mere “curtains,” only needed to keep the elements out.

Historian Carl Condit writes,

The utilitarian advantages of steel framing were enormous and immediately obvious to architects, builders and owners. First was the possibility of getting rid of a supporting wall, with a consequent reduction in weight and an immense increase in height. The steel necessary to carry a tall building weighs only one-third as much as bearing masonry for an equal number of stories. The virtually unlimited increase in glass area, up to 100 per cent of coverage, allowed the maximum admission of light. The slender columns and wide bays offered greatly increased freedom in the disposition of interior space. Economy in cost of materials together with speed and efficiency of construction convinced even the most skeptical owners of the superiority of steel or wrought-iron framing.

In 1889, New York City soon entered the skyscraper game with the construction of the Tower Building at Lower Broadway. Architect Bradford Lee Gilbert also had an Eureka moment on how to build tall on the narrow lot. In 1905, he recalled that,

One day the idea came upon me like a flash that an iron bridge truss stood on end was the solution to the problem.

Gilbert’s building, also, was not a pure skyscraper, since the top floors included load-bearing masonry walls. New York and Chicago each tried to say they were the first. But after reviewing the evidence, Sarah Landau and Carl Condit write,

The only fair conclusion to be drawn is that architects, engineers and builders in New York, Chicago and Minneapolis were simultaneously and independently developing the iron skeleton system.

While the steel skeleton—and elevator—are perhaps the sine qua non of the skyscraper, there are also about a dozen or so systems that go together to create the whole skyscraper machine. Necessary is the technology for wind bracing; anchoring the structure to the ground; fireproofing; heating, cooling, and ventilation; plumbing; and lighting and electrical wiring. Based on his research, Condit concludes,

If we are tracking down the origins the skyscraper we have certainly reached the seminal stage in New York and Chicago around the year 1870.

So 1870, 1885 or when? Well, the debate about which was the first can be tedious, but here are other candidates that have been put forth.

In 1870, the Equitable Life Assurance Society completed its 7-story headquarters in lower Manhattan. Its revolutionary idea: include two steam-powered elevators for the office tenants. Perhaps for the first time in human history, businesses paid more money to rent the higher floors than the lower ones. Again, Landau and Condit:

All the exceptional features of the Equitable Building—its elevator-predicated height, “fireproof” constructions, extensive iron framing, large window area, and rent-free owners quarters—justify the title “first skyscraper.”

Another possibility is the Tribune Building, completed in New York in 1875. It was likely the first office building to use height to show off the power of its occupant, the New York Tribune—the brainchild of Horace Greeley. Media Studies expert, Aurora Wallace, writes,

The nine-story height ensured that the tower would be taller than any existing New York office building and was thus neither an arbitrary choice of height nor one based on the functional space requirements of the newspaper. The design and size of the Tribune building was primarily governed by the enhanced public image that would be garnered for the newspaper and only tangentially by the potential economic benefits of building tall.

Or perhaps the first skyscraper was the first building to actually receive the moniker “skyscraper.” Before they were applied to tall buildings, the word referred to other extremely tall or high phenomena, including sail masts, horses, and fly balls in baseball.

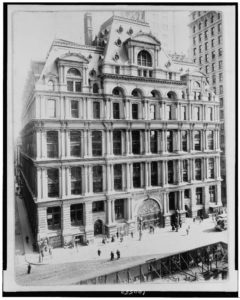

As late as 1883, the Chicago Daily was referring to a series of buildings in New York and Chicago as “sky-scrapers.” My searches through historical newspaper archives produced a December 19, 1882, New York Sun article entitled, “Another Sky Scraper Down Town,” which specifically refers to the construction of the Mutual Life Insurance Company building in Lower Manhattan, completed in 1884.

We can continue in this way ad naseum. While I, too, cannot provide a definitive answer, here’s my opinion. There are three characteristics that make a skyscraper a skyscraper: (1) a building that is significantly taller than typical buildings in a given locale; (2) uses an all-steel skeleton frame, and (3) satisfies an economic need.

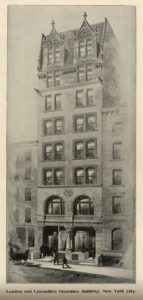

Based on this criteria, the first skyscrapers would be the 10-story Lancashire Insurance Building in New York (1890) and the 16-story Manhattan Building in Chicago (1891), designed by William Le Baron Jenney.

Regardless of which building is chosen, what is certain is that by 1890, most of the technological barriers to building height had been removed in a way that allowed for supertall structures which could rise beyond 15 stories. By the turn of the 20th century, 25 to 30 floors (100 meters) were at the vanguard.

In the next post, we will review the history of building height over the 20th century and see how the skyscraper grew up.

This is a wonderful blog post. I am curious about one issue: As I recall from some earlier writings along these lines, the notion of extremely tall structures was, of course, nothing new in the 1860-1900 period, but prior to that period they relied upon stone engineering (pyramids, etc). But one book which I cannot remember the name of nor the author, suggested that the birth of skyscrapers was somehow due to the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge completed in 1886. It’s suspension towers, at the time, completely dwarfed all the structures in lower Manhattan. Is there any validity to that? Perhaps you address that in your book, but it isn’t mentioned in this blog post. Perhaps also it is no particular real significance, but I thought I would bring it up. To an amateur’s perspective it does seem like a convincing idea.

I don’t know the source of the book on the Brooklyn Bridge, but I take your point. I think one of the reasons why the debate about the first skyscraper is so enduring is that there is no single definition of what make a skyscraper a skyscraper. In Gerard Peet’s article, for example, (http://global.ctbuh.org/resources/papers/download/321-the-origin-of-the-skyscraper.pdf), he argues for Rome’s Insulae Feliculua, as well as other structures built around the world in the 15th and 16th centuries. I guess the lesson: take your pick!

Perfect, re Insulae Feliculua. Yes and one could go back to the Tower of Babel, which never was built, as far as any archaeologist knows, or as you point out numerous other structures. I need to dig up that book with the bit about the bridge. The suspension towers are nearly 300ft (100m) tall, and they took quite some time to build, as you know–completed right around the same time as some of the iron and steel core buildings you mention. I suspect that there were entrepreneurs who didn’t quite find the upstaging of their businesses by a bridge particularly amusing. Also, recall that within those structures inside the Brooklyn Bridge towers are livable areas. I’ll try to find the reference and apologize for posting comments with nothing to back it up. In the end, maybe now it is far easier to discuss what scrapes the sky? But the origins of these ideas are important.

Enjoyed reading very much about the skyscrapers and looking back at the history of our nation thanks Paul Keating. Age 91