Jason M. Barr July 15, 2020

Captain Kirk: It exists on the hate of others.

Mr. Spock: To put it simply. And it has acted as a catalyst, creating this situation in order to satisfy that need.–In “Day of the Dove,” Star Trek (S3:E7)

E Pluribus Unum?

America in the 21st century is a deeply divided country. Looking back at the nation’s long history of economic growth and technological improvements, one might have thought that the political, social, and economic divisions among us would have been considerably lessened by now.

There are, to be sure, many bright elements. Healthcare is vastly improved as compared to a century ago. New technologies have created more free time and given us additional social, political, and economic freedoms to decide what to do with our time and personal resources. The tremendous income generated by our economic system has allowed more people than ever before in the history of humanity to enjoy cultural activities, literature, art, and nature. Computing technologies provide a degree of interconnectedness never witnessed in human history.

And yet, despite these advances, the full promise of democracy and economic growth has not been completely realized. Our democratic institutions are increasingly controlled by those with the money and resources to steer policies in their favor. After declining for a half-century, income inequality reversed itself, and today the wealthiest one percent garner about a quarter of the nation’s income. In 2017, the U.S. dumped 6.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into our atmosphere. The legacy of American slavery and the racism it created remains a wound on the body politic. And just as importantly, modern media technology, instead of being used solely for the improvement of the common good, is exploited to divide and engender hatred between us.

Star Trek and the Fear of Hate

Gene Roddenberry, who created Star Trek, saw, in 1966, the world at a pivotal moment—one with boundless possibilities for its future, yet one still trapped by excessive greed and aggression. The starship Enterprise, in the original series (TOS), captained by James T. Kirk in the 23rd century, roamed the galaxy encountering species that either tested humanity’s progressiveness or presented foils. These encounters were continued in the 24th century in The Next Generation (TNG) with Captain Jean-Luc Picard at the helm of the Enterprise.

The show offered two contrasting visions: first was a kind of “paradise on Earth,” where we retain our freedoms and individualism to seek out maximum fulfillment, but only on the condition that we also check our hatred. Second, by presenting an array of other societies, be they Klingon, Romulan, Cardassian, and so on, we could better understand the hazards of succumbing to violence. The main lesson is that hatred and division can destroy all that we have gained through hard work, cooperation, technological improvements, and faith in democratic institutions. The warnings remain as relevant today as half a century ago.

The Market for Hatred

Homo sapiens, through its evolutionary past, is programmed to create psychological divisions between those perceived as in-groupers versus out-groupers. Members of the ingroup tend to trust each other and collectively work toward the welfare of the whole. On the other hand, those they perceive as outsiders are viewed as potential threats. The social emotion of hatred is the extreme feeling of anger toward those who are perceived as “the other.”

These feelings are directly tied to perceptions of fairness. We all desire equal access and opportunities or to be treated similarly in similar situations. Hatred develops when one group perceives that the fairness rules are being skewed. Hatred, of course, exists within all of us, but not everyone has it triggered. Collectively, as the wealth of the humans of Planet Earth has grown, we have, bit by bit, replaced war and divisions with commerce and cooperation.

Enter the Hate Entrepreneur

However, because our latent instincts for hatred remain, they can be exploited by a “hate entrepreneur,” who “sells” hate through modern media technology. Knowing that there exists a latent demand, hate entrepreneurs can peddle hate through the distribution of false information about the other, in exchange for power, adulation, and profit. The consumer of hate consumes the false information because it stokes feelings of being treated unfairly, despite their being part of a “majority” group.

Hate and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

In most situations, we go to the marketplace for goods like milk or computers because it offers a win-win proposition. A seller brings milk to the market and gains a profit. The buyer gets to enjoy a milkshake. And that’s that. Those who prefer another beverage are not affected in any way by the transaction. But the market for hate is very different. The group that hates harms their fellow humans in some way, either through unequal treatment, generating fear, or by producing outright violence. The gains to the hate consumer occur directly on the backs of others, forcing the victims to respond in some way to preserve their well-being.

This situation introduces what economists call the Prisoner’s Dilemma, illustrated with the following story. Two robbers are caught in the act of robbing a house. They are both hauled off to separate jail cells. The police say to the first one, “If you confess to the crime, you can go home, and your accomplice will go to jail for ten years. But, if you remain silent, and your accomplice confesses, you will go to jail for ten years, and your accomplice goes free. However, if you both remain silent, you will each go to jail for two years. And if you both confess, you will each go to jail for four years.”

What Would You Do?

Are you willing to remain silent? What incentive does your accomplice have to keep his mouth shut? If he knew that you were going keep quiet, he would blame you and walk free. If he knew you were going to rat him out, he would also blame you, since going to jail for four years is better than ten. In the end, the “rational” thing to do is for both robbers to confess to the crime. As a result, they each go to jail for four years. But if each chose to remain silent, they would have collectively done better for themselves. But they can’t—because they are apart and are unable to coordinate their actions (or enforce them).

The critical point of the Prisoner’s Dilemma is that individuals’ actions are not separate and independent of the collective whole. The decision of one can help or hurt someone else, depending on the action. The “dilemma” is that if they could work together to cooperate, they could do better than if they acted independently. The “freedom to choose” in this example means society is worse off—each person harms the other by being selfish. In a way, the consumption of hate is a form of Prisoner’s Dilemma. The haters gain a short run “victory,” but at the expense of fueling further divisions, which will lead to more conflict, or, in the extreme, war.

Star Trek and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

One of the themes that runs throughout the original series is that if humanity is to save itself, it must overcome its instincts for hatred. Mr. Spock is offered as a role model in this regard. Spock has suppressed (repressed?) his emotions so deeply that he is (nearly) incapable of feeling hatred (though it is severely tested on several occasions, such as in Plato’s Stepchildren (S3:E10) where he is mentally tortured to cry). He embodies the idea that only through logic and the dispassionate pursuits of science, art, and philosophy, can we peaceably co-exist.[1]

Implicitly, the show recognizes the nature of the Prisoner’s Dilemma by frequently depicting this “game,” and having the crew choose between “cooperate” (not killing) versus “defecting” or “cheating” (killing). But the show is also aware of something else that social scientists have discovered—that when the Prisoner’s Dilemma game is played repeatedly, frequently, and with little likelihood of ending soon: there is an opportunity for the players to learn to cooperate.

The reason is that the players face a new choice. If they select the selfish option now, they possibly relinquish any future benefits from cooperation because their rivals are not likely to cooperate in the future. On the other hand, when the benefits to cooperation are substantial and can be received over a long time (think of enjoying the fruits of peace), the temptation to “cheat” by being selfish can be avoided. Captain Kirk is frequently tested in some way by being forced to choose whether to kill “the other” because it seeks to kill Kirk. Each time, he suppresses his rage because he knows that getting the rush of victory now is not worth sacrificing the (possible) future gains of peace.

The Arena

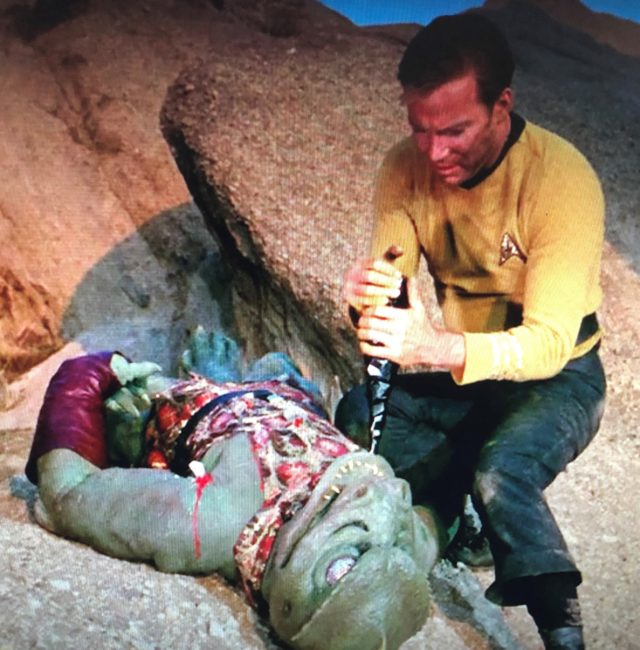

In the “Arena” (S1:E18), for example, Kirk finds himself on a strange planet face to face with the Gorn, a reptilian humanoid. They are required by an alien being to fight each other to the death. After a series of battles and cat and mouse chases, Kirk gains the upper and approaches the creature, drunk with rage, ready to kill him. But he does not—he checks his anger and refuses to kill. The alien being, Metron, is pleased. He appears and turns to Kirk:

Metron: By sparing your helpless enemy who surely would have destroyed you, you demonstrated the advanced trait of mercy, something we hardly expected. We feel there may be hope for your kind. Therefore, you will not be destroyed. It would not be civilized.

Kirk: What happened to the Gorn?

Metron: I sent him back to his ship. If you like, I shall destroy him for you.

Kirk: No. That won’t be necessary. We can talk. Maybe reach an agreement.

Metron: Very good, Captain. There is hope for you. Perhaps in several thousand years, your people and mine shall meet to reach an agreement. You are still half savage, but there is hope. We will contact you when we are ready.

The Evolution of Cooperation

In 1984, the political scientist, Robert Axelrod, published a book called “The Evolution of Cooperation.” In it, he describes an experiment that he performed. He asked several scientists to submit proposals for how they would play when engaged in a Prisoners Dilemma game that was repeated many times. They were asked to offer any type of strategy they wanted, and one which they thought would be successful (note that similar to the robbers example above, one can assign points to the different outcomes). For instance, they could submit, “always cooperate,” or “cooperate three times and then defect one time,” and so on.

He took the proposals and created a simulated battle. Each scientist’s strategy was pitted against the others in a series of one-on-one round-robin competitions. The strategy that earned the highest total score was called “Tit for Tat.” It said, start by cooperating and then from there play the same action that your rival played in the past round. If your opponent cooperated, then cooperate; if not, then don’t. This strategy rewards cooperation but also punishes a rival’s selfishness. It is simple and clear and can help the two players move to a situation where they are always cooperating.

Star Trek and Tit for Tat

This tit-for-tat strategy was implicitly suggested, for example, in “A Taste of Armageddon” (S1:E23). Kirk and crew beam down to the planet, Eminiar VII, where their leader, Anan, warned them to stay away. They find the inhabitants engaged in a brutal war with neighboring planet Vendikar—but by computer. Each time the enemy hits, they must send their “causalities” to a disintegration chamber. For centuries, each society has maintained this status quo, as being better than actual war. Kirk, in the end, destroys the computer. Anan is horrified.

Anan: You realize what you have done?

Kirk: Yes, I do. I’ve given you back the horrors of war. The Vendikans now assume that you’ve broken your agreement and that you’re preparing to wage real war with real weapons. They’ll want do the same. Only the next attack they launch will do a lot more than count up numbers in a computer. They’ll destroy cities, devastate your planet. You of course will want to retaliate. If I were you, I’d start making bombs. Yes, Councilman, you have a real war on your hands. You can either wage it with real weapons, or you might consider an alternative. Put an end to it. Make peace.

Anan: There can be no peace. Don’t you see? We’ve admitted it to ourselves. We’re a killer species. It’s instinctive…

Kirk: All right. It’s instinctive. But the instinct can be fought. We’re human beings with the blood of a million savage years on our hands, but we can stop it. We can admit that we’re killers, but we’re not going to kill today. That’s all it takes. Knowing that we won’t kill today. Contact Vendikar. I think you’ll find that they’re just as terrified, appalled, horrified as you are, that they’ll do anything to avoid the alternative I’ve given you. Peace or utter destruction. It’s up to you.

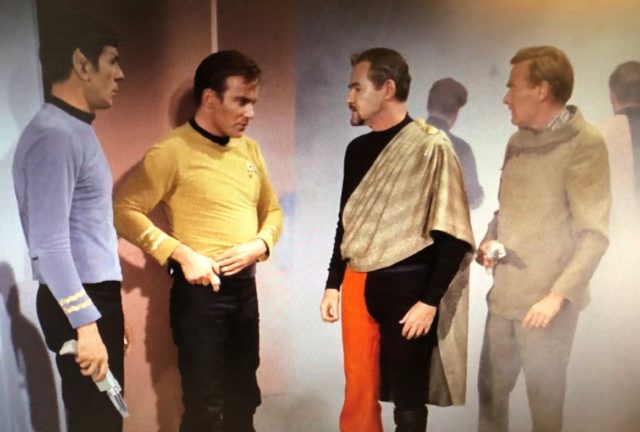

Recognizing the Hate Entrepreneur

Hate, however, can only be stoked and grow by the work of the hate entrepreneur who peddles it for his gain. The TOS episode, “Day of the Dove” (S3:E7) remains timely. A strange alien entity starts antagonizing the Enterprise’s crew, but makes it seem the work of the rival Klingons, who also think the Enterprise is victimizing them. Each time someone is harmed, the entity heals them so the fighting can be renewed. The entity feeds off the negative energy and violence. Realizing its modus operandi, Kirk must convince the Klingon leader, Kang, to cease hostilities, which he is loath to do.

Kirk: All right. All right. In the heart. In the head. I won’t stay dead. Next time I’ll do the same to you. I’ll kill you. And it goes on, the good old game of war, pawn against pawn! Stopping the bad guys. While somewhere, something sits back and laughs and starts it all over again.

McCoy: Let’s jump him.

Spock: Those who hate and fight must stop themselves, Doctor. Otherwise, it is not stopped.

…

Kirk: Be a pawn, be a toy, be a good soldier that never questions orders.

…

Spock: All fighting must end, Captain, to weaken the alien before our dilithium crystals are gone.

…

Kang: Out! We need no urging to hate humans. But for the present, only a fool fights in a burning house. Out!

A Future of Peace?

So, which future will we choose? One where our society continues to permit the hate entrepreneurs to peddle their faulty wares, or one where we recognize the hate entrepreneurs for what they are? The lesson of the Prisoner’s Dilemma is that there are two ways to achieve the everyone-cooperates outcome. One is that we can collectively agree to work together (and also punish any “defectors”); and the other is to set the stage so cooperation can naturally emerge over repeated interactions.

In the first case, this would require that citizens vote into national office leaders who make laws against peddling false information, just as it is illegal to falsely label consumer products. In the second case, the “defectors”—the consumers of false information—must be willing to switch their actions and to give “cooperation” a try. They must see the future rewards of working together are greater than any short-term rewards of selfishness. Again, this requires leadership, if not outright, legislation.

We can at least begin by revisiting the lessons of Star Trek, which dramatically shows us that hate and paradise on Earth are inherently incompatible.

Continue reading other posts on Star Trek and economics here.

—

[1] Though Dr. McCoy is continually reminding Spock that by having no emotions, he is also unable to enjoy the benefits of human emotions, such as love.