Jason M. Barr February 5, 2019

Today, just over half of the world’s population lives in cities. By the middle of the 21st century this figure will likely be near 75%. The future is decidedly urban. Those who care about the well-being of humanity must naturally be concerned with how cities work; for when they function well, people are happier and healthier (and other species as well).

The Dream of Urban Utopia

At least since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, when the skies were black with coal dust, and poor factory workers huddled together in squalid housing, city planners and utopians dreamt of manufacturing the well-ordered city. They envisioned a place where each worker has access to clean air, open space, and roads laid out in a rational manner. They advocated for better living through planning—the imposition of top-down solutions to urban problems.

At the national level, the planning of entire economies has come and gone. Experiments with socialism in the Soviet Union and China, for example, have ended in failure. Yet, the urge to impose plans and rules on cities remains strong—an urge deeply rooted in the DNA of local government, be it through zoning, strict building regulations, or detailed glossy planning documents that seek to dictate the future city form.

Order without Design

But those who study the economics of cities remain skeptical that order can be imposed from above. As Alain Bertaud argues in his masterful book, Order without Design, strict planning doesn’t work for nations, and it doesn’t work cities. Yet, to this day, the planners of the world just don’t trust the marketplace. They observe disorder and conclude it must be bad. Bertaud sees otherwise. The market does create order, but only if we let it.[1]

For over a half-century, Bertaud was a city planner. His first job, in 1965, was as an “Urban Inspector,” charged with issuing (or denying) housing permits in Tlemcen, Algeria. Over the years, he rose to the position of Principal Urban Planner at the World Bank. Throughout his long career, he has helped plan or consult on numerous projects in cities of all stripes and sizes from those in socialist Russia and China to Haiti and India. He has observed much about the way cities work, or not.

The Blind and the Paralytic

During his professional journeys, he also attempted to gain deeper insights about cities by studying economics. As he chronicles in his book, this was an unusual route; most planners know very little economics and they remain uninterested in the subject. For him, however, it was a chance encounter with an urban economist while working in Port-au-Prince that set him on the path. Even so, his research also led him to conclude that while economists have generated deep insights in the into the nature of cities, they are not engaged with the daily problems of running a bustling metropolis:

We are facing a strangely paradoxical situation in the way cities are managed: the professionals in charge of modifying market outcomes through regulations (planners) know very little about markets, and the professionals who understand markets (urban economists) are seldom involved in the design of regulations aimed at restraining these markets. It is not surprising that the lack of interaction between the two professions causes serious dysfunction in the development of cities. It is the story of the blind and the paralytic going their owns ways: The planners are blind; they act without seeing. The economists are paralyzed; they see but do not act. (p. 2)

The argument of the book is thus quite simple: that planners and economists should work together when developing urban policies. That much seems reasonable—who would dispute that two heads are better than one? But the next premise is likely a harder pill to swallow—that the city planners of the world need to learn and understand how markets work. This is particularly difficult because economics says that the planning profession has gotten things wrong. There are only a limited number of reasons planners should intervene. The rest can, and should, be taken care of by the market itself.

Insights from Urban Economics

Bertaud argues that urban economic theorists—through the use of math-based models—have generated several vital conclusions that need to be mastered if cities are going to function better.

The City as Labor Market

First is the need to view the city—fundamentally—as a labor market, as an agora or bazaar where residents can easily find matches between their own skills and the needed skills of employers. Successful matching is the path to higher incomes and the end of poverty.

Maximum Flexibility

Second, the city-as-labor-market requires maximum mobility and flexibility, so that people and businesses can find each other, and they can readjust their matches and housing as circumstances change. Geographic mobility is the route to social and economic mobility.

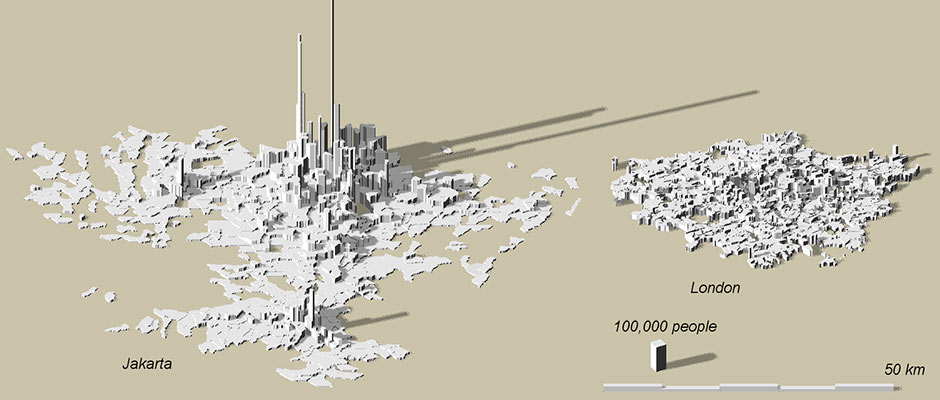

Population Density Emerges by Choice

Third, people don’t like to commute, and they are willing to pay higher housing costs to live close to their jobs. Therefore, long commutes must be compensated through lower-cost housing in the suburbs. If land markets operate properly, dense living in smaller units in the central city and less-dense living the suburbs is the result of households balancing the tradeoff, and thus choosing what’s best for them.

Sprawl is not Inherently Bad

Fourth, the footprint of the city—how far it extends into the countryside—is a result of the economics. Cities expand further out because residents have higher incomes, a more efficient transportation network, and/or a less productive agricultural hinterland. Sprawl is thus, at its heart, a result of free choice, and can be an efficient allocation of land.[2]

Land Markets are Vital

Lastly, labor markets and residential flexibility must be mediated through a well-functioning land market, where the prices of land reflect the relative demand for different locations throughout the city. When events change, the prices need to change too in order to incentivize repurposing the land for its most productive use.

Planning Reduces Flexibly

The planning profession, however, is more focused on limiting or restricting land uses and housing density. Rules are designed to preserve or prevent “bad” things from happening. Building height limitations are meant to lower density and shadows. Public housing projects are designed to give minimum size shelter to the poor. Zoning rules prevent single-family homes from being converted into apartment buildings. Bars and restaurants are banned from getting too close to residences.

The fundamental problem with these regulations is that, in an attempt to create order, they ignore the need for flexibility and density. Prohibiting or slowing down this flexibly drives unintended outcomes that are often worse than the problems they seek to solve. Bertaud offers numerous examples from his global sojourns. But here I highlight a few.

Cities with No Land Markets

Land use in China and Russia during their socialist eras keenly demonstrate—albeit in an extreme fashion—what transpired when order is imposed from above. Say a factory was originally placed in the city center. But if the factory’s technology became obsolete or its products were no longer needed, what happened to the abandoned building and lot? Not much. As Bertaud writes,

Because the land occupied by a firm was not recognized to have value per se, it could not be recycled for another use or passed to another user, who in a market economy, would have been bidding for it. As Chinese cities expanded, there were pockets of industrial land located close to the city center that could not be reconverted for other uses, because no mechanism existed to do so. (p. 13)

The point is that to function well, a city needs a relatively open market for land. The more restrictions placed on the land the less it can be used to serve the needs of its residents as times change.

Public Housing on the Urban Fringes

After the end of apartheid, the South African government embarked on a program to build affordable housing for the poor. As well-intentioned as the plan was, it ignored the underlying spatial structure of the country’s cities. By placing the housing in the suburbs where land was cheap, it could be built at lower cost, but was far away from employment nodes. As Bertaud writes,

The massive subsidized housing projects may have further fragmented the labor market of South African cities, contributing significantly to lower their productivity….[The] high unemployment rate cannot entirely be attributed to the poor location of the subsidized housing scheme, but certainly, this massive program of building individual housing units in widely dispersed communities with no economic and speedy means of transport did not help. (p. 273)

Master Plans

Today, the pull to create master city plans remains strong. Bertaud highlights one from Hanoi, created in 2010, called “Hanoi Capital Construction Master Plan to 2030 and Vision to 2050.” But as scientific and precise as the plan claims to be, it ignores the economic realities that are going to dominate the city in the 21st century. For example, it calls for a large agricultural belt for rice paddies just outside the western part of the central city. The noble intentions of protecting agricultural jobs and open space by imposing land uses will backfire:

The arbitrary assignment of workers to rural or urban jobs is solely based on planners’ choice and is therefore unlikely to be implemented: no zoning regulations can force people to work in one sector of the economy rather than another! It is very likely that in 2030, owners of rice paddy fields in the agricultural belt will face difficulties finding enough labor to work in their fields, because of competition with better paying urban jobs. (p. 135)

What Should Planners Do?

Bertaud argues that the need for urban planning is still crucial, but just not in the way most planners believe. Their job should be to perform four vital tasks, and leave the market to do the rest.

Create Efficient Transportation Systems

First is to design and manage transportation systems to promote maximum flexibility and speed of movement. The book demonstrates that there is no one best way to do this, and each city needs to develop a method based on its history and the preferences of its residents. Cars can work as well as subways, if policies are correctly designed.

Public Goods

The next intervention relates to so-called public goods, such as parks, streets, and other infrastructure. Here planning is vital, as the city needs to provide them since the market will not. However, the trick is not to go overboard. Creating vast greenbelts that enclose the city and generate more rural space than is needed for recreation distorts incentives, reduces flexibility, and raises housing prices. Planners should be ready to add needed infrastructure as the demand for it emerges.

Externalities

Third is regulating the negative spillovers, or externalities, that arise from concentrated living. Driving, for example, generates congestion and pollution during rush hour, and contributes to climate change. Planners need to focus on how to accurately price the use of roads to minimize the negative impacts. Similarly, with building heights. If tall buildings create shadows, then the solution is not to impose arbitrary building height limits, but to adjust the incentives, say through (Pigovian) taxes, so people internalize their impacts on society at large.[3]

Constant Vigilance

Lastly, planners should maintain constant vigilance about the effects of regulations on cities. Rules that were designed decades ago and are no longer relevant should be removed. Planners thus need to regularly evaluate if the suite of rules and plans remain in harmony with the actual behavior and needs of its residents or if it hinders the market from doing its job. Building flexibility into the planning process will allow planners to solve problems as they crop up, without creating new ones along the way.

Politics is also the Problem

This book is important because it highlights the necessary relationship between economics and planning. Successful cities exist in the balance between the efficiency of markets and the curbing of its excesses or failures. Too much regulation increases housing prices, fosters poverty, and reduces social and economic mobility. Too little management can generate congestion, pollution, too little green space, and excessive uncertainty.

But one can’t but help think that it is not simply enough for planners to understand economics (and for economists to understand planning). Urban policies emerge from political decisions. In democratic societies, for example, policies are the result of a compromise to please—or not upset—as many constituencies as possible. So even when planners can design good policies, bad politics may drive decisions that prevent their implementation, or water them down into irrelevance or even harmfulness. It is one thing to design optimal policies, but quite another to incentivize people to go along with them. Allowing cities to reach their full potential requires flexibility, and flexibility means change. People resist change. Understanding the reasons for this is also vital for urban health.

The Future?

Bertaud’s book, I hope, will have an impact on the way planners see cities. Though I fear this will not be the case. My sense is that the planning profession views economics—the dismal science—as being out of touch with the nuts and bolts of running cities (and too mathematical). While economists feel that economic theory and statistical analysis is more important than the nuts and bolts of running cities.

Each field has its own perspectives and way of doing things, and which continue to be propagated through graduate programs, conferences, and professional and academic journals. To be respected in each profession requires one adhere to the rules of its respective game. The tyranny of disciplines locks practitioners into their own walled intellectual cities. Bertaud’s own path is the exception that proves the rule. His route was idiosyncratic, springing from his personal curiosity combined with a lucky encounter with a friendly economist.

A book like this is crucial, but change must also come from within the academies that train professionals. There needs to be more fundamental shifts in world views about the nature of urban policies and the practice of planning. New interdisciplinary programs that bring economists and planners together so they can learn from each other and allow policymakers to think more deeply about the role of land markets, and the nature of incentives and unintended outcomes would be a good start. It will take a lot more people like Bertaud to build momentum. So much rides on our ability to get cities right.

—

[1] Ironically, Jane Jacobs argued, in her 1960 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, that planners should not plan; that markets are the best way to create order. Yet, somehow, today Jacobs is the Patron Saint of Modern Planning. Her words were interpreted to mean that cities should preserve or promote the Greenwich Village neighborhood that she liked and deemed good. Planners have substituted Le Corbusier for Jacobs, but the impact on cities is just as real, albeit in a different way.

[2] As I have argued elsewhere, this issue is made somewhat more complex in the United States because of the heavy subsidies for car use and mortgage deductions which encourage sprawl. Furthermore, there is also evidence that while people like the idea of having big yards and free-standing houses, they appear to systematically overvalue them and undervalue the cost of commuting before purchasing a home. But given the large cost of moving, they often find themselves locked-in to a less desirable situation than they anticipated.

[3] Bertaud is not alone in his feeling that cities have over-regulated land markets. In the words of urban economist, Edward Glaeser, “Almost none of the land use regulations that cities have ardently adopted for over a century have been justified by any serious quantitative work. The existence of even the smallest externality, such as a shadow, has been seen as justification for massive interventions in the housing market.”