Jason M. Barr April 10, 2019

[This is part two of a three-part series on New York’s first zoning regulations, enacted in 1916. Part I focuses on the history of the regulations. This post revisits the reformers’ thinking through the lens of modern economics. Part III will argue that the ideas and rules from 1916 helped to set the stage for today’s NIMBYism and housing affordability problems.]

From the point of view of public advantage the distribution of population is very important. Most of the evils of city life come from congestion of population. In precisely the measure that the city’s population can be distributed will those evils be mitigated. As the number of families housed per 50-foot lot increases:

(1) The provision of light and air, so essential to health, vitality and comfort decreases.

(2) The opportunities for personal contact and thus for the spread of communicable disease increase.

(3) Noise and confusion incident to increased street traffic increases.

(4) Each family suffers more and more from the noises from neighboring families.

(5) Privacy is diminished.

(6) The children have less and less opportunity for outdoor play.

(7) The danger from fire, both to life and property, is increased.

(8) The transit lines become more and more congested during the rush hours.

It is therefore essential in the interest of the public health, safety, comfort, convenience and general welfare that a housing plan be adopted that will tend to distribute the population and secure to each section as much light, air and relief from congestion as is consistent with the housing of the entire population for a considerable period of years within the areas accessible and appropriate for housing purposes.

– Final Report of the Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, City of New York, 1916

At the turn of the 20th century, urban reformers looked around and did not like what they saw. The central city was too congested. Tall buildings were shooting up too rapidly, placing unsuspecting neighbors in shadows and drawing more traffic. The city’s poor were packed too tightly in the slums, causing diseases, vice, and more poverty. And factories were spewing pollution willy-nilly. The reformers thus came to one conclusion: density was bad. The solution: scatter the population. They must be drawn (or pushed?) into single-family housing surrounded by greenery, not only for their individual betterment, but for the good of the whole.

The Birth of Zoning

As a result of their ideas, in 1916, New York City enacted the first comprehensive set of regulations on land use for any city in the United States. It was “comprehensive” because the rules were applicable to every single piece of property within the municipal boundaries. Other places, like Chicago, Boston, and Los Angeles had experimented with specific building controls in particular districts, but New York was the first to implement rules city-wide.

The decision was to carve up the city into three different types of zones, that regulated height, usage, and lot coverage, respectively. There was nothing inevitable about the choice of land use regulation through zoning, but it was what the city chose to do, based on the political economy of reform at the time. To propose something too restrictive or aggressive would have meant instant veto by those constituents harmed. To do nothing was unacceptable. In the end, the reformers devised a compromise plan—a set of proscriptive real estate rules about what could not be built, and to let the market take care of the rest.

In Lieu of Planning

As historian Keith Revell argues, the zoning founders favored direct planning—concerted actions by the government that would deconcentrate the population—but this was too hard a sell in laissez-faire New York. They couldn’t force people to move, and they couldn’t violate the sanctity of private property. So, they did the next best thing—they regulated real estate construction, while grandfathering what was already built. The new structures had to take up less space, both on the lot and in air, with the aim of reducing the number of occupants per acre of land. Vast swaths of New York City were going to be suburbs, whether the people wanted it or not.

Enter Economics

Here I want to revisit their thinking about population density. Over the last century, economists have developed a rigorous approach to understanding human behavior. They use the methods of the social sciences to investigate cause and effect. I would like to argue that we should employ them to reevaluate the policy actions of the past. The decisions that the reformers made a century ago continue to impact our lives. They established the ground rules for urban land-use policies, and many of our current ones have emerged from them. In essence, their actions generated what economists call path-dependence. They laid down the road on which we now walk. We should review this path to see if was a good one.

Also, the reformers, because of their passion and vociferation, have dominated the historiography. They painted a very dark picture about life in the central cities, while offering utopian pastorals of the suburbs. Take the advocate Jacob Riis, who took his camera into the slums of the New York and revealed how “the other half” lived. He depicted the worst of the worst but was not able to see the true economics of these areas. As a result, we inherited a collective belief that these neighborhoods were terrible, terrible places with little thought to the benefits they were providing. Or, as Charles Madison writes in the preface of a 1971 reprint:

What Riis saw in the late 1870’s and 1880’s was the cankered fruit of decades of callous exploitation and neglect by rapacious landlords in connivance with venal and vapid politicians.

Theory

Today economics has two complementary modes of investigation. First is theory, which, usually, comprises a set of mathematical models or equations designed to investigate the relationship between the costs and benefits of taking different actions and the social or economic outcomes they generate, along with indications of whether they are “good” or “bad” (as defined by specific metrics).

Since World War II, economic theory as applied to cities has been a vibrant field and has created a cannon of ideas that help us think critically about both the costs and benefits of city life. At the time the zoning rules were being written, there was no such cannon. Reformers were unduly focused on the costs of city living and downplayed or ignored its benefits. Economic theory paints a much more nuanced picture of cities and suggests policies that can provide improvements without generating perverse incentives that do more harm than good.

Measurement

The other element of modern economics is that of measurement, what has come to be known as econometrics. Economists employ rigorous statistical analysis to decipher patterns and test hypotheses generated by the theory. The economics profession is deeply engaged in measurement to “witness” how, why, and when different incentives generate different outcomes. Thanks to improvements in computing and the availability of new data sources, econometrics has entered a kind of golden age. New types of analyses can be done, and new answers can be given to age-old questions.

Going in Blind

In the 1910s, when the city reformers were writing the regulations, they were, in some sense, going in “blind,” in at least two ways. First, they had no economic theory to guide them; and second, they had very limited tools for measurement (and virtually no tools for the study of cause and effect). This is not to say they didn’t do their homework. The reformers, and the various commissions they established, studied the ills of urban density in great detail. They reviewed the policies of other cities and they carefully itemized all the various problems befalling the metropolis. They interviewed experts in health, real estate, planning, transportation, etc., who offered their learned opinions on the problems at hand. These official also had behind them several decades of research on diseases and health problems from poor sanitation and drainage in the tenement neighborhoods.

But, they wrote the zoning rules and regulations simply from what they thought was “reasonable.” In other words, they just kind of made it up as they went along, based on what they saw in other cities around the world, what they could pass into legislation, and what would survive court challenges.

Hindsight Glasses: Reevaluating Population Density through the Lens of Economics

With this said, I want to play the game of “Hindsight is 20-20,” by looking back at their thinking and reevaluating it through the lens of modern economics. In particular, I want to focus on one key goal of the zoning plan—deconcentrating the population (and will discuss other elements in the next post). I want to argue that economic theory—and the evidence for it—strongly suggest that there are a just a handful of factors that drive population density across the city, and to ignore or fight against them leads to a worse-off place.

Today, arguably, the one model that unites all urban economists is the so-called standard land use model (also called the Alonso-Muth-Mills model, as it was developed and elaborated by these three economists. A synthesis is provided Jan Brueckner). It is, of course, an abstraction that removes many of the complicating details of urban existence. But through simplicity we can get to the core and draw forth the very essence of why cities exist and how they operate. Once we understand this, we can then focus how policies can help or hinder urban growth and well-being.

The model begins with the assumption that the fundamental problem of city life is that people need to make location decisions. Households must find employment and places to live, and businesses need to choose places for their production and to get workers to come these locations. The dilemma here is that not everyone can be at the same place at the same time—thus making geography itself a scarce resource that must allocated in some way. The model is designed to answer three questions. First, what is the end result of a market-oriented allocation process? Second, is the allocation “good,” according to some metric? And third, when there are some changes to incentives, how does space get reallocated?

Location, Location, Location!

First, we need to begin with the idea that price of geography is the result of an auction-like process. People and businesses bid for the right to occupy different locations throughout the city. The key insight of the model is that in a relatively free market household’s decision about where to locate are grounded in the trade-off between living close to work and having quick commute versus living far from work and having a long commute. The “balancing mechanism” is the price of land, and therefore, housing.

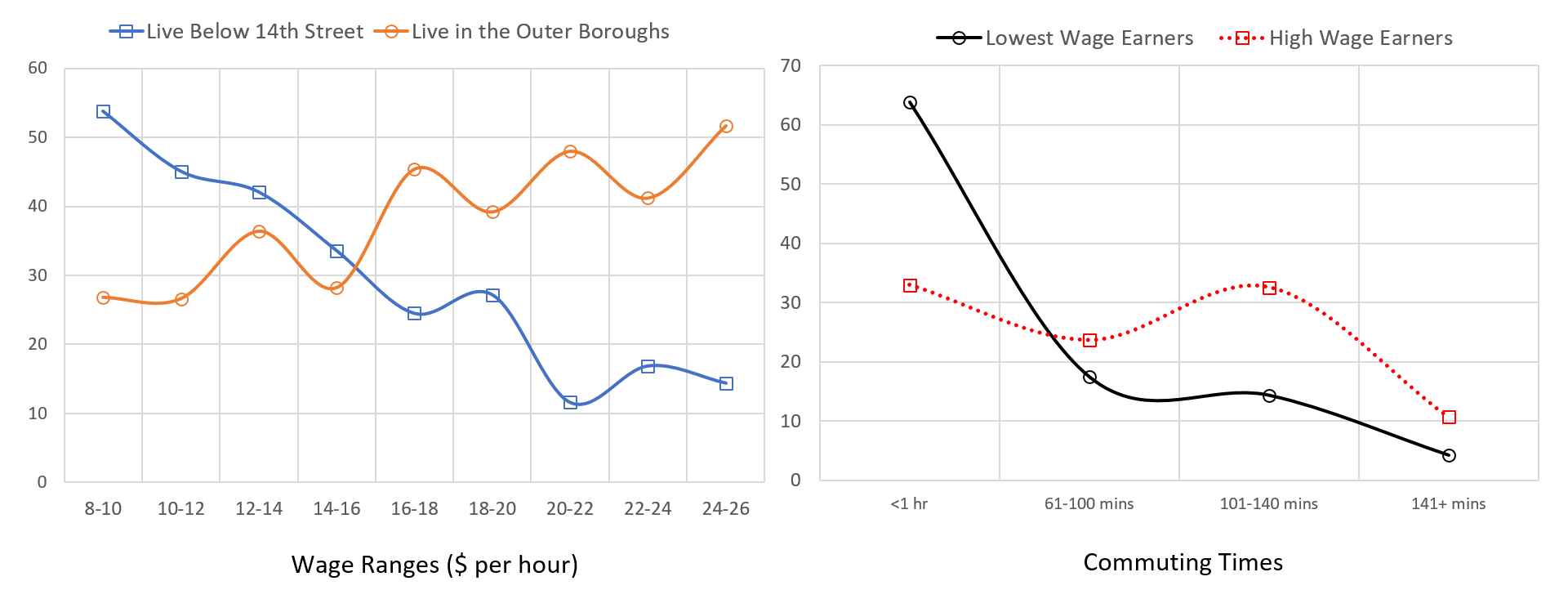

To be compensated for a long commute, households are willing to live further away only if housing is cheaper, and, which allows them a bigger house. If they move closer to the center, commuting becomes easier and so they bid up the price of housing for the right to have a lower commute. But more expensive housing means they must economize on it and live in smaller units. If lower income people have less money for commuting, they live closer to work in smaller units.

Developers respond to the higher price of land by building apartment buildings in the center. Where the demand is great but the ability to pay is low (in the tenements), they subdivide the apartments into very small units. Further away from the center, where the price of housing is cheaper (on a per square foot basis), developers provide one- and two-family homes on larger lots. They key point is that this tradeoff between access to work versus the price of housing is the vital “glue” that holds the city together and makes it function property. It generates the near-universal pattern of high density in the central city and low density in the suburbs. It creates order without design. But economies grow, incomes rise, and cities invest in transportation and infrastructure. The model shows how changes in these things alter the distribution of population to retain this order.

Transportation

If innovations in transportation, such as electrification for subways and trolleys, or automobiles, makes commuting faster and cheaper, all else equal, the model demonstrates that the population will naturally de-densify overtime. Simply put, faster commutes means living in leafier suburbs is more attractive. In 19th century New York, the default mode of commuting for the poor was walking. For deconcentration to take place, transportation must be cheap and fast.

Income

As incomes rise, people naturally want more housing (in economic parlance, housing is a so-called normal good). In this case they have two choices. First, they can stay put in the central city and occupy relatively more space. For example, the tenement dwellers might decide not to take in boarders, or they can rent two adjacent apartments and join them into one. Or again, they can move further out to the suburbs where housing is relatively cheap, and they can get more of it, as a result.

The Evidence

In summary, the model illustrates that density across the city is the result of people and businesses finding the best balance between being close to each other versus having more space. Close is expensive so they economize on space and live densely. Far away requires more time traveling back and forth, and so space is cheap and plentiful, with few people per acre. But if transportation becomes cheaper or incomes rise people will naturally choose less dense living conditions. What does the evidence say? Both for historical New York and modern times, across the world, the evidence strongly demonstrates this pattern.

Income

The standard model distinguishes between population density that arises from how much housing households can afford (more income means more housing) and how much floor area is provided per acre (more floor area more density). Building density, in and of itself, is not the only cause of population density because density is also influenced by income. Think of the apartment buildings along Central Park—they are dense structures, but each one contains relatively few people.

Jane Jacobs, in her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, argues that in her former tenement neighborhood in Greenwich Village, “unslumming” was occurring naturally as people used their rising incomes to refurbish and occupy more housing within the tenements. Older reports on immigration observed that once a certain level of social mobility was achieved (and which was obtainable in the “slums”), people naturally left the dense neighborhoods for airier climes. To quote one 19th century expert on immigration, Kate Holladay Claghorn,

Many tenements in Jewish quarters are owned by persons who formerly lived in crowded corners of others just like them; and from this population comes many and many a Broadway merchant and professional men in plenty. It is a common saying that from Hester Street to Lexington avenue [sic] is a journey of about 10 years for any given family.

Census Tract Evidence

Looking at New York today, a statistical (regression) analysis shows that much of the differences in population density across census tracts can be explained by two variables—the amount of building space per acre (more space, more density) and the median household income (higher income, less density). Applying these findings to the “slums” of 19th century New York would suggest that, holding building area constant, when tenement dwellers found their incomes doubled, the neighborhood would naturally de-densify by about 28%. Looking at the semi-skilled profession of bricklayers in New York, real incomes increased by 126% between 1880 and 1914. Even before zoning was implemented this rising income was likely driving large increases in the amount of housing consumed per family.

More broadly, nearly every single older industrial city in the world, experienced declining density over the course of the 20th century, be it London, Paris, Sydney, New York, or Chicago. More income has universally meant more housing per household, regardless of land use policies or location on the planet.

Transportation

A 1911 study on the concentration of factories and workers, found that low incomes were compelling workers to live within walking distance of their jobs because they couldn’t afford mass transit. The study found a clear pattern: as incomes rose, workers lived further away from the center (and spent more time commuting). They needed the income to pay for the daily travel.

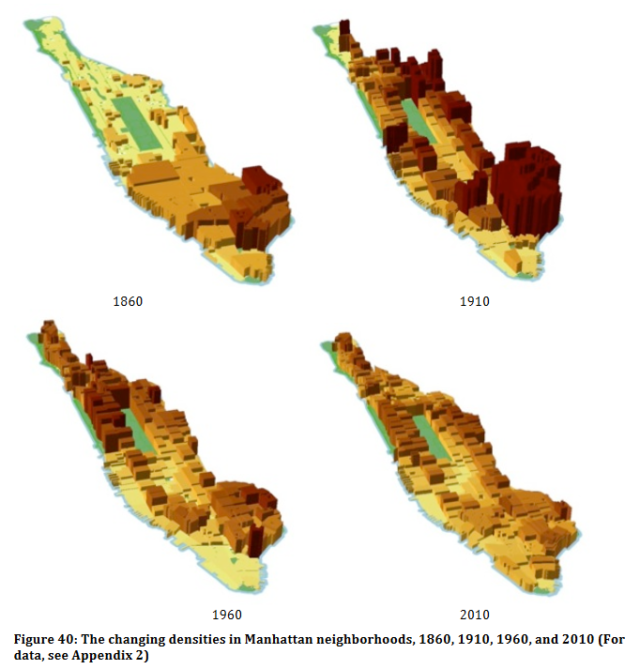

The degree of de-population of Manhattan after the opening of the subway suggests that it did more good for the residents in the overcrowded neighborhoods than any zoning reforms. Once workers, with their rising incomes, had access to fast and cheap mass transit, they took advantage of this and moved to the outer boroughs, where they re-formed their ethnic enclaves, in places like Woodlawn, Canarsie, Pelham Parkway, and Williamsburg, but in modern, larger units. Between 1910 and 1920, Manhattan lost 2% of its population, while the city as a whole saw a rise of nearly 18%. The fact that the island lost only 2% was due to the opening up of northern Manhattan to development after the 1 train was completed. The Lower East Side emptied out, losing nearly a quarter of its former residents.

Revisiting 1916

The growth of incomes and the investment in mass transit, via the subway, and street cars, were already doing the work that the zoning reformers were trying to accomplish through land use regulations. But why didn’t they see it? First, they were ideologically driven by a Garden City mentality. They couldn’t see apartment buildings as good for people, and they saw density as a driver of all that was bad about urban life. They wanted to impose suburbia on the metropolis and to do this they needed to create large swaths of land that would be reserved for one- and two-family homes—through limits on use, height, and lot coverage.

The zoning reformers were working in parallel, but independently of, the transit planners, when the subway was being built out into the far reaches of the metropolis (see Richard Plunz). The zoning planners knew that subway lines and streetcars would generate high density areas along the routes, and they feared these areas would become new Lower East Sides in Brooklyn or Queens. They didn’t fully understand that the economics of rising income and cheap transportation would generate density, but not the overcrowding they saw in Lower Manhattan.

As will I argue in more detail in the next post, this is not to say no reforms or interventions were best, but it is to suggest that their ideas of scattering the population through zoning, in hindsight, was well-intentioned, but somewhat misguided. The natural patterns of density are the result of the choice of individuals; as their circumstances change, they need to have the flexibility to readjust so they are just as well off.

Better Strategies

If you indirectly “force” people to occupy too much housing than they want because of limits on construction then you move them away from what they prefer and are worse off as a result. For example, if a city underbuilds apartments and overbuilds single family housing because of the zoning rules, it harms the poor by pushing them further away from their jobs and future opportunities by increasing the time and cost of commuting and reducing social and economic mobility. It also increases sprawl and forces the poor to over-consume the amount of housing that’s right for them and their budgets. Furthermore, restrictions on housing construction raises the prices for everyone. While the slums weren’t pretty–and there were many problems–they were places that fostered economic and social mobility, in part because of access to cheap housing close to work.

If the zoning framers wanted to do the most good for overcrowding, they should have focused their energies on working with transit planners to maximize the amount of fast and reliable transportation. They could have worked with labor groups and companies to raise the minimum wage or increase unionization rates. The optimal strategy was, and is, to focus on eliminating poverty and promoting upward mobility.

Ironically, for early 20th century New York, zoning did not generate large negative unintended consequences. Half of the city was yet to be built up, and so the urban hinterlands provided vast swaths of land for affordable housing near the subway lines (and for automobile drivers, who were yet to come). In essence, the zoning regulations of 1916 did not limit the city’s real estate growth, but it did establish the concept that restricting the total amount of housing was an acceptable policy goal. But in 1916, nobody could imagine the affordability problems to come a century later. The seeds had been planted, but they just took a century to flower.

Continue reading Part I of this series.