Jason M. Barr February 27, 2024

[Note: Starting Monday, March 4, 2024, Gerard Koeppel and I will be co-teaching a six-week online course on the history of the Manhattan grid plan for the Gotham Center for New York City History. More information and registration can be found here.]

Planting the Seeds

In April 1811, New York’s Street Plan Commission created the now-famous grid plan—but on paper only. The commissioners handed the City their map and said, “Goodbye and good luck.” Two of them, Simeon De Witt and Gouverneur Morris could now focus on their Erie Canal work. And the third, John Rutherfurd, was never very interested in the position.

The municipality had to find a way to make the plan a reality, and somehow, it did. As historian Hilary Ballon writes,

The miracle of the 1811 plan was that it was enforced. It took about sixty years for the grid to be built up to 155th Street, sixty years during which mayors and administrations, interest groups and aesthetic values frequently changed and might have undermined the plan—but the grid prevailed.

Randel Returns

However, the Common Council was not completely lost. They still had John Randel, Jr, who surveyed Manhattan for the Commission since 1808. Nobody knew Manhattan better, and with his expertise and diligence, he was best qualified to figure out where the streets and blocks would actually go. At age 23, Randel was hired by the Common Council, as its chief engineer to make the grid plan a reality.

Randel remains an enigmatic figure. While highly motivated and brilliant, he was also a crank. He spent much time and coin in litigation against those he thought were cheating him of his due. Though Randel would go on to other surveying and engineering projects, his work in Manhattan was arguably the high point of his career.

Nonetheless, we can take a few minutes to chat with him.

“Q&A” with John Randel, Jr.

Q: When you were doing your surveying work, did you encounter any troubles?

A: Col. Richard Varick, who was Mayor of the city of New York for the twelve years from 1789 to 1801, always became bail for my appearance at Court, when, in the absence of the Commissioners, I was arrested by the Sheriff, on numerous suits instituted against me as agent of the Commissioners, for trespass and damage committed by my workmen, in passing over grounds, cutting off branches of trees, etc., to make surveys under instructions from the Commissioners. The persons who instituted those suits were a few of the numerous opponents of the field of operations of the Commissioners, which included their property in the then new Plan for the city, many of whose descendants have been made rich thereby.

Q: Were you able to fully complete your work?

A: The time within which the Commissioners were limited by Statute to make their Plan of the streets, avenues, and public places on Manhattan or New York island, and also to lay out the same upon the ground, being barely sufficient to enable them to comply with the letter, although not fully with the spirit of the Statute, by only making the Plan therefor…without locating the whole of any one of the avenues permanently upon the ground; and also by establishing on the ground only one point in some part of 16 out of the 155 streets laid out on their Plan, which subsequently required and received 1,549 marble monumental stones and 98 iron bolts, at their several intersections with the avenues; and directing that the spaces between all the streets falling between each two of those points named and described by them therefor, should be of equal breadth, without specifying the breadth of any of those spaces, or locating any of those streets permanently upon the ground.

Q: After the Commissioners submitted their street plan in April 1811 did you have to look for another job?

A: The Commissioners reported to the Corporation this insufficiency of time to complete their work, and recommended that, as their Secretary and Surveyor I had become acquainted with the ground, and the Plan for laying out the same, I should be employed to complete the work according to it.

In accordance with this recommendation of the Commissioners, I was employed under contract with the City Government to lay out those streets and avenues and public places upon the ground, according to the Plan reported therefor, and to place monumental stones and iron bolts at their several intersections—these amounted to 1,647—and also to survey and make maps of the possession, fences, and bounds of real estates, and of all buildings upon that part of New York Island on which I had placed monumental stones and bolts, all of which work…I completed about the year 1821.

Q: Did you ever see any famous New Yorkers on your way to work?

A: Our office at Christopher street was, at the time, more than a mile north of the settled part of the city, which then terminated south of Lispenard’s Salt Meadow (now Canal street). And during the time it remained there, I boarded in the city, and in going to the office I almost daily passed the house on Herring street (now No. 293 Bleecker street) where Thomas Paine resided, and frequently, in fair weather, saw him sitting at the south window of the first story room of that house….”

Q: Some people think the Grid Plan was the worst planning mistake of all time. What is your view?

A: This Plan of the Commissioners, thus objected to before its completion, is now the pride and boast of the city; and the facilities afforded by it for buying, selling, and improving real estate, on streets, avenues, and public squares, already laid out and established on the ground by monumental stones and bolts, at the cost of the city; and of greater width and extent, safety from conflagrations, beautiful uniformity and convenience, than could otherwise have been obtained…and admitting free circulation of air through them; thereby avoiding the frequent error of laying out short, narrow, and crooked streets, with alleys and courts, endangering extensive conflagrations, confined air, unclean streets, etc. must have greatly enhanced the value of real estate on New York Island, thus laid out on the Commissioners’ Plan.

Implementing the Grid

After Randel placed his markers—mostly in the middle of people’s farm or even at their front doors—the plan had to be put into action. In the 27 years from 1830 to 1856, there were nearly 200 openings of road segments or public squares. A road would be constructed when property owners formally petitioned the government. Then the work began: Trees were torn down, the ground was dug up, and the land was leveled to the proper grade.

But such a process was not easy. The land had to be created if the street was in a valley. The bedrock had to be chipped away if it was on a hill. Manhattan was also crisscrossed with streams and ponds. Most of the time, they were filled in with dirt and rubble from removing the hills.

The Tab

Initially, owners had to bear the burden of the costs. First, they were credited for the value of their property taken for the street, and then they were charged 70% of the cost of creating it. If there was a difference, it had come out of the landowners’ pockets. While many of them, no doubt, were angry that they had to pay a significant fraction of the expense, the process of assessing property owners for improvements on and around their property was an age-old tradition that went back to the Dutch and British colonial days as well. After the Civil War, as the city’s government became larger and more “governmental,” the City picked up half the costs.

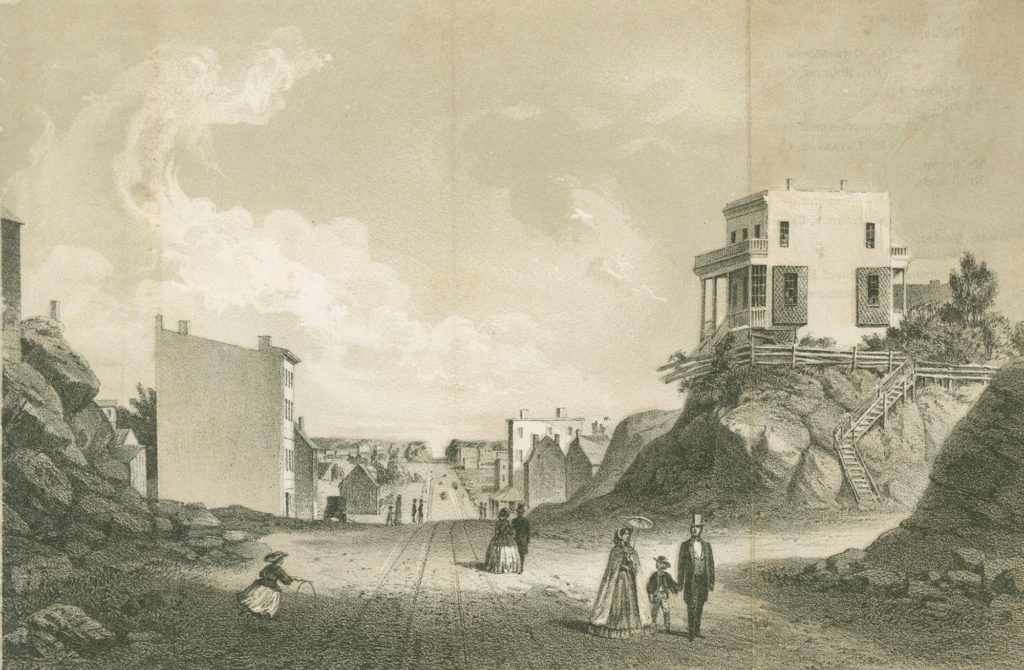

The Mountain Myth

For example, an 1861 drawing of the newly formed Second Avenue at the newly formed 42nd Street illustrates this transformation. The avenue appears as a kind of urban gorge, enclosed by steep hills of bedrock. On the east side, a solitary farmhouse is perched 20 feet atop an extrusion of schist. A temporary wooden staircase strapped to the rock allows access to the domicile. The image has helped fuel the conventional wisdom that the grid plan was a great leveler, tearing the city down to a uniform, flat topography. But to what extent is this true?

Based on my statistical analysis of Manhattan, however, the results suggest that rather than a great leveling, the island was subject to a great smoothing. In fact, about two-thirds of all blocks had changes of less than 10 feet, and 40 percent had average elevation changes of less than 5 feet. The modal change was to add between 0 and 10 feet, which was also due to infill along the riverbanks. Nearly as much of the island was “brought up” as it was “brought down.” Valleys needed to be filled in while the hills were lowered. The average change across all blocks, in fact, was an increase of elevation of 1.7 feet.

The Lots Myth

Another myth that pervades the historiography is that the plan created the typical small lots of 25 feet by 100 feet. In 1894, noted architect Ernest Flagg voiced a popular belief about Manhattan’s lot sizes: “The greatest evil which ever befell New York City was the division of the blocks into lots of 25 x 100 feet…for from this division has arisen the New York system of tenement-houses, the worse curse which ever afflicted any great community.”

Flagg was lamenting that builders chose not to erect housing on larger lots, which, he argued, would have alleviated over-crowding and disease. While he was not commenting on the grid plan per se, it is easy to see how people have come to confuse Manhattan’s small lots as emanating from the plan itself. Today, the common perception remains that the small lots were a result of the plan. But the grid plan had nothing to say on this matter.

The Real Story

The ubiquity of the (approximately) 25 x 100 square foot plot size was a mainstay of land subdivisions long before 1811; it was the de facto standard from the earliest time of settlement and never existed in any legal statutes.

Instead, decisions about lots and blocks were made on an ad hoc basis based on the residents’ incentives. 25 x 100 square feet represented the best balance between several competing considerations. A two- or three-story house of a 20- or 25-foot width and 50-foot depth would be a reasonable size, with a functional backyard with space for a privy and a rainwater cistern. Additionally, wooden joists used to support the floors could not be longer than 25 feet without having to add internal columns to support the floors. If a family wanted a house larger than 25 feet across, it would have added a new expense. For most homeowners, the additional space was not worth the cost.

When the Commissioners chose their block sizes of either 800 or 920 long feet by 200 feet wide, they implicitly encouraged this age-old tradition to continue. Landholders would subdivide the blocks into two equal north-south halves of 100 feet each, and then the lots on each side would be subdivided equally into 20 or 25 feet and sold off as individual parcels. Even today, nearly 40% of Manhattan’s lots retain their “standard” size, but don’t blame the grid plan.[1]

Remapping

Since the grid plan was initiated as an idea—as a piece of paper—it could, in principle, be altered, and altered it was. The 19th century would witness several changes to the original blueprint—not so many that they would fundamentally re-form what it was, be enough to add a modicum of diversity to the pattern. Alterations took two types—additions to the avenues and changes to public spaces.

New Avenues

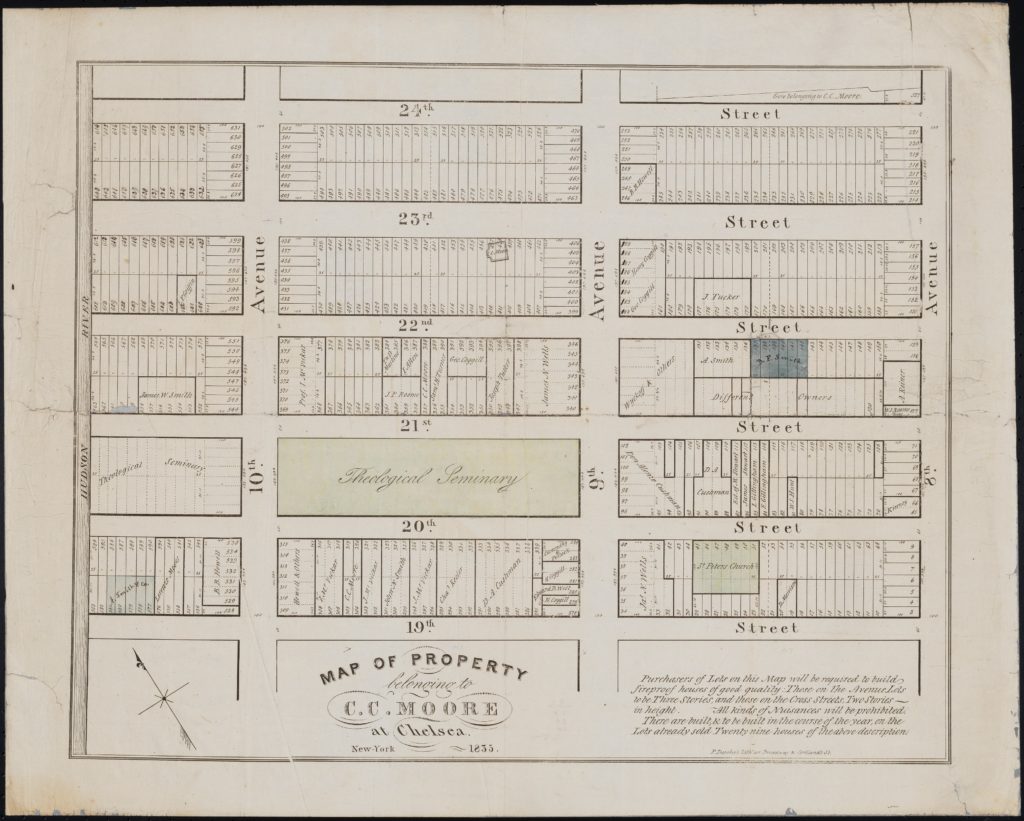

One of the earliest changes emerged from the efforts of wealthy landowner Samuel B. Ruggles, who owned property on the east side, north of 14th Street, which has subsequently become known as Gramercy Park. To increase the value of his holdings, Ruggles designed a small square with homes surrounding them. He also petitioned the Common Council to create a 75-foot-wide avenue from 14th Street to 30th that would then cut in half the blocks between Third and Fourth (later Park) Avenues. Ruggles named the new avenue Irving Place after his friend Washington Irving.

As grid historian Gerard Koeppel writes,

Ruggles’s plan looked good on paper but not the ground. A creek, the original Dutch “Crommessie” from where “Gramercy” derived, wound through one side of the property in a deep gulley surrounded by swamp; the other side was high hill. Ruggles eventually spent $180,000 dumping a million cartloads of hill into the valley, burying the creek and filling in the bogs.

Other landowners appreciated the smaller blocks created by Ruggles’s new avenue, giving them more valuable frontage. As a result, Irving Place was continued northward under the name Lexington Avenue, running up to East 132nd Street, where it intersects with the Harlem River. Similarly, Madison Avenue was mapped in the 1830s, partly from Ruggles’s urging. Madison divided Fourth and Fifth Avenues in half, and it also runs up the rest of the island.

Broadway

Broadway, a major thoroughfare since the Dutch days, was one of the most important nods to historical lock-in. The grid plan had no use for Broadway, and was “cut from the show.” However, Broadway north of 23rd Street (then called Bloomingdale Road) remained in use. In 1838, Broadway/Bloomingdale was officially re-mapped and folded into the street plan. From a planning perspective, Broadway’s diagonal run from 10th to 72nd Streets makes it interesting. When it intersects other avenues, it lends itself naturally to the formation of squares.

As a result, Broadway’s path has sparked the creation of Union Square, Madison Square Park, Herald Square, Times Square, Columbus Circle, and Verdi Square at 72nd Street. The beautiful Flat Iron Building—so named because its triangular shape was reminiscent of a clothing iron—was produced on the three-sided lot where Broadway intersects Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street. As a side note, Broadway today continues its run long outside of Manhattan, ending some 20 miles north of Gotham.

Parks

The original street plan called for relatively few parks, and over the 19th century, the “park scene” would change. First was the shrinkage: The extensive parade grounds at 23rd Street from Third to Seventh Avenues were scaled back to create Madison Square Park. Other squares on the street plan map were de-mapped at the urging of local property owners who wanted to sell their land on the free market.

However, places where the geology and topography dramatically changed and were unsuited for housing were converted to parks. For example, Morningside Park, which is situated where Manhattan’s geology shifts. The high ground on the west is Manhattan Schist. The low ground on the east is Inwood Marble. Because marble erodes faster than schist, the line where they meet creates a steep slope. In 1873, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux of Central Park fame were commissioned to put this sloped schist to good use.

In the case of St. Nicholas Park from 127th to 141st streets, it was originally land condemned for the construction of the Old Croton Aqueduct in 1885. New York State laws of 1894 and 1895 authorized the creation of a public park instead.

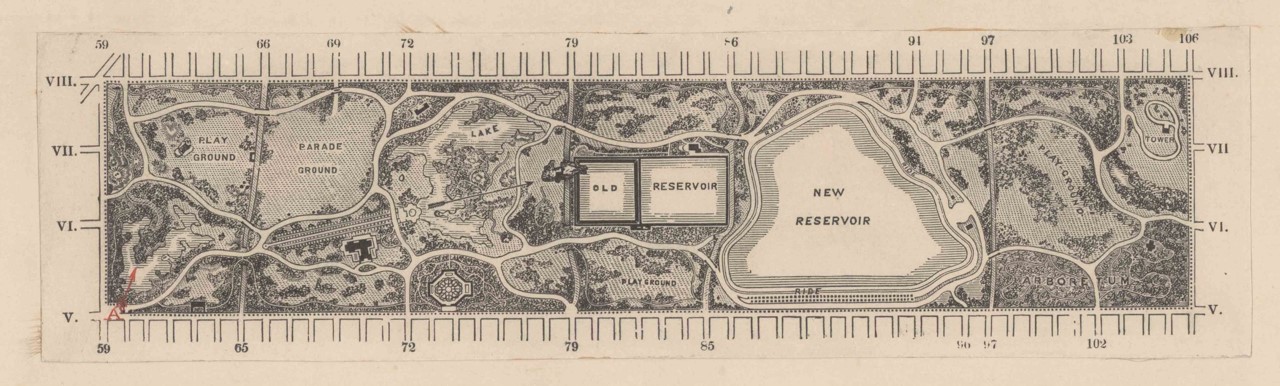

Central Park

But as the relentless pace of removing the city’s natural landscape continued, many wondered if their entire island would be soon covered in cobbles and bricks. The street plan commissioners’ claim that the rivers—“those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan island”—were enough to give Gotham open space and fresh air was not correct. The greatest irony of the grid plan, thus, was the creation of Central Park, one of the world’s best public spaces.

By the mid-19th century, several coalitions would unite to advocate for a large urban park. The rise of industrialization and the commitment formation of slums filled with impoverished immigrant workers generated political and economic strife. Reformers saw urban parks as a way for people of different stripes to come together, and for the working classes to be becalmed by nature’s charms. The wealthy also demanded park space, as the grid was eating up land for their peacock-style strolls and horse racing hobbies. Finally, were the property owners whose land would abut any such large park, and stood to gain from the rising property values.

In 1853, a state law initiated a park of 778 acres (later expanded to 843) in the center of Manhattan, where the land was rocky, and the City still owned significant acreage that was once the Common Lands. The Central Park Commissioners chose Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to implement their Greensward design. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Straight out of Manhattan

Though Manhattan has had an outsized role in Gotham’s history, it’s land area is only 7.5% of the city. It’s small stature but large influence begs the question: Was it’s unusual grid plan replicated in the other boroughs of New York? We will dive into this question in the next post. Stay tuned….

Continue reading the rest of the series on Manhattan’s grid plan here.

—

[1] Using the NYC PLUTO file, I counted the number of Manhattan lots between 15 and 30 feet wide and 90 by 110 feet wide. The results show that they constitute 16,800 out of 42,700 lots.

Leave a Reply