Jason M. Barr March 17, 2020

Your New Job

Imagine the governor of your state announces that she is going to create a brand-new city out of whole cloth. The state has purchased 200 square miles (519 km2) of farmland (around the size of Chicago) and will begin auctioning off lots for development. The governor is working with officials to build the transportation and infrastructure network. But she has turned to you with a critical mission: to formulate the regulations about building heights. Your job, as Chief Building Heights Planner, is to develop a series of plans about how dense or tall the structures can be throughout the city.[1] Where should you begin?

Options

You can think of the possibilities as existing along a continuum. On one side is to write no rules and allow buildings to be as tall or as dense as developers want. If someone builds a 100-story skyscraper in the middle of a leafy residential neighborhood, so be it. If builders cover 100% of the lot and put their neighbors in darkness, that’s okay too.

The other extreme is to order the city entirely. Say you build a 3D model in your office and arrange the exact scale, density, and height for every structure. There can be no deviation. Building #1 must go here and must be so many stories. Building #2 must go there and have exactly so many floors, and so on.

Option three, of course, is somewhere in between, where you designate some rules on height and density, and let the real estate community figure out the rest. But even within this option, there’s a wide spectrum. Do you set limits for everyone? Do you restrict hieght in some places but not others?

How FAR Can You Go?

After doing a little research, you find one popular regulatory tool is to limit the so-called floor area ratio (FAR).[2] The FAR dictates how much building space can be constructed based on the lot size. For example, in an older (pre-car) dense apartment-based neighborhood, the rules might specify a maximum FAR of 3. This means that on a 2,000 square foot (186 m2) lot, the most a new building can have is 6,000 square feet (557 m2) of living space.

If we assume, for example, that each household in the building rents 600 square feet (58 m2), then that building will have ten units. A FAR increase to 4, means the structure can be 8,000 square feet (743 m2), with 13 units. If each apartment, on average, holds two people, the FAR-3 building has 20 people, and the FAR-4 building has 26 people.

Building Heights

FAR limits say little about building heights directly. In a FAR-regulated city, the height is chosen by the developer, based on what works best for her. In the FAR-3 example, she can build a three-story building that takes up the entire lot, or she can erect a six-story building that covers only half the lot. Yet both will hold the same number of people.

Thus FAR limits mean that building bulk and height are substitutes—the taller the building goes, the narrower it must be, with more open space surrounding. This strategy presumably mitigates the negative impacts of tall buildings, such as shadows on neighboring properties. For these reasons, FAR regulations are popular among planners. They are a simple way to reduce the density of both people and buildings.

Wheel of FARtune?

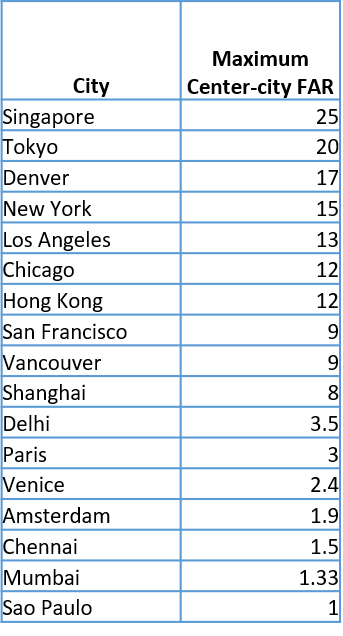

By how do planners choose the “correct” FAR values across the city? The answer is: they just pick numbers that seem right—usually some higher numbers in the central core (say 8 to 15), medium numbers in the dense residential rings (say 2 to 4), and much smaller figures further out (typically one or less). These values are often based on what “feels” appropriate, or are politically salable, and are not tied to any economic research that attempts to weigh the costs of restrictions versus their benefits. A survey of maximum FARs in central cities around the world shows that planners have chosen a wide range of numbers. Their arbitrariness is also supported by the research discussed below.

FARnomics: The Economics of FAR Regulations

Recently, economists have begun to question the wisdom of choosing urban FARs based on planners’ notions of what constitutes the “good” city. Economic analysis about FAR regulations starts with a series of questions: What would density look like without any FAR limits? Under what conditions would restrictions help improve city well-being? When would FAR restrictions make things worse?

The Order without the Design

As Alain Bertaud discusses in his 2018 book, Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, a bustling metropolis without any FAR restrictions will generate a natural order. In the central city, where land values are high, developers will be incentivized to provide taller builders on relatively small lots. As land values decline moving away from the center, buildings will get shorter, on average.

A well-functioning land market will also create a predictable pattern for population density. Near the center, where land is expensive, households will live in apartment buildings. Further away, where lots are cheaper, people will occupy larger houses. Thus, density will be high near the center and fall from there. This outcome is based on the choices of households and represents what they prefer—better accessibility to the center versus more housing and open space further away. The price of land is the nexus between what households want and what kinds of real estate will be constructed. Overly burdensome regulations will distort land prices and prevent them from efficiently allocating housing demand with housing supply.

Key Assumptions

The optimality of this natural order is based on a few assumptions. First is that there are no negative spillovers or externalities from this arrangement. That is, the tall buildings in the city don’t create excessive shadows, promote hyper-congestion, or generate undue health or social problems. Additionally, economists assume that residents or visitors are indifferent to the building designs and shapes that would spring up when the real estate market is relatively open. Tall or dense buildings, it is assumed, don’t offend people’s aesthetic sensibilities.[3]

The presence of these possible harmful elements has been the driving force and justification for imposing FAR restrictions. City officials argue they are necessary to relieve congestion, provide open space, improve urban health, and make the city “beautiful.” But the economist would respond: if this is so, what are the “right” set of restrictions (assuming that restrictions are the best way to solve these problems) that best balances the trade-offs. The truth is, as of this writing, no one knows. The proper calculations have yet to be done.

The Case of New York

Take New York City as an example. The city’s FAR-based regulations were enacted in 1961. They were designed to reduce density as compared to the 1916 zoning codes, which were seen as not being restrictive enough. While small FAR changes (rezonings) in different neighborhoods occur from time to time, there has been no systematic change in the regulations in over half a century. In other words, the same FAR codes, more or less, are in effect today as when John F. Kennedy was President and when The Andy Griffith Show was one of the most popular TV shows in the nation. (If you’re young enough not to know what I’m talking about then I think I’ve made my point.) Once FAR regulations are imposed, they are nearly impossible to dislodge, despite mounting evidence that they are harming the city.

Furthermore, in 1961, when these regulations were set, planners with who felt that promoting the tenants of modernism was surely the path to urban utopia. Clearly, by 1975, when New York City was ready to declare bankruptcy (see “Ford to City: Drop Dead”), utopia was on the minds of few. Sticking with these outdated zoning rules is like trying to use a Commodore 64 computer to process “big data” data.

Estimating the Impacts of FAR Regulations

Recently, however, the urban economist Jan Brueckner, of the University of California-Irvine, and co-authors have studied the impacts of FAR restrictions around the world. His research asks the question: What are the costs of excessive FAR restrictions, imposed in the name of improving the common good?

Bengaluru (Bangalore)

Indian cities have some of the lowest central-city FAR values in the world. Planners have established them, evidently, as a backdoor way to impose their notion of a better city, and because officials couldn’t provide the city services needed to support a dense urban core. As Brueckner and Bertaud (2005) write, “It is believed that ‘excessive’ density results in a loss of environmental quality and increased traffic congestion. In addition, higher densities would place greater demands on urban infrastructure, which Indian cities, plagued by weak technical capacities and inadequate tax revenue, feel ill-equipped to provide at appropriate levels.”

Unlike New York (with a maximum central-city FAR of 15), and Shanghai (with a maximum central-city FAR of 8), Bengaluru has a central-city FAR capped at less than 1.5. This number is considered reasonable for a suburban residential neighborhood of garden apartments, but absurdly low for a central business district in a metropolis with 8.4 million people.

In their paper, Brueckner and Bertaud explore the economics of these excessive restrictions. They demonstrate that these FAR limits promote denser development in the suburbs than would otherwise be the case, and create larger, more sprawling cities. The attempt to limit building heights in the center to reduce congestion inadvertently creates more congestion by promoting more driving. If we think about the (lightly-regulated) city as a block of clay. The draconian FAR restrictions are tantamount to smashing the clay. The result is a flatter, wider entity.

They perform some calculations for Bengaluru, and find that the excessive sprawl reduces average household income from extra commuting by 2%. It’s also worth noting that, in recent years, Bengaluru has achieved an international reputation as a tech hub. Limiting densities may have other consequences, such as reducing the opportunities of firms and workers to interact and learn from each other. These restrictions are likely reducing citywide productivity than otherwise.

101 Indian Cities

In a 2012 paper, Brueckner and his collaborator, Kala Seetharam Sridhar, investigated the impact of FAR restrictions on urban sprawl for 101 municipalities throughout India. First, they find a wide distribution of maximum central-city FARs. The lowest city has 1, and the highest has 4.125. The average city in the sample has a central-city FAR of 2.87. Again, compared to other cities around the world, these figures are low.

They next study how these FAR restrictions impact the total land area of municipalities, which is a measure of urban sprawl. Based on their analysis, they conclude that if the average city in India raised its central-city FAR by one unit (e.g., go from 2 to 3), the, it would need 20% less land area to hold the same amount of people. Or, on the flip side, on average, a city that decides to lower its central-city FAR by one is generating an increase in its land area by 20%.

Land Values in China

A well-functioning land market is the main means by which the city orders itself. If land values rise at a specific place, it signals that the residents want taller buildings. If FAR regulations are overly tight, they can lower the value of land, which will then generate buildings that are economically “too short,” denying residents the opportunity to live and work in the location of their choice.

Brueckner, and his co-authors, Shihe Fu, Yizhen Gu, and Junfu Zhang, study the land market in China. Unlike the U.S., there is no private property. Instead, all the urban land is “owned” by the respective municipal governments, who sell long-term leases to developers (70 years for residential and 50 years for commercial). The revenue from these land-leases is used to fund infrastructure and other government projects.

Because municipal officials control this land, they can impose FAR regulations on the developers when they win the right to build. We tend to think of modern Chinese housing as mostly dense, high-rise apartments. This is true, but municipal officials frequently require developers to adhere to relatively low FARs of between 2 and 3. The effect is to create a Corbusian city of tower-in-the-park complexes.

Findings

To study the question of how these FAR restrictions impact land (lease) values, they constructed a very large data set with over 50,000 transactions across more than 200 cities from 2002-2011. Each land-lease transaction also includes the maximum FAR requirement. Across cities, they find that the average residential FAR is only about 2.4.

The authors also find that the higher the FAR restrictions, the greater it reduces land values. Loosening these restrictions would allow land prices to more accurately reflect the benefit of various locations throughout the city. The results suggest that the current FAR values are actually not allowing central locations to be as dense as residents would want.

The Trade-offs

Since Chinese officials lease the land, one would think they have the incentives to provide even looser FARs to increase their revenue streams. However, local leaders must balance the revenues from these land leases with the costs of building infrastructure. So the FAR restrictions may not only be related to notions of sound design principles but also limiting urban density growth to something that will not overly burden the current level of infrastructure. Or, as Brueckner et al. hypothesize, “In this sense, local officials behave as net revenue maximizers, taking into account the public costs associated with land development into account.”

However, if city size or budgetary issues were important than the data would show a relationship with FAR restrictions. But, based on their analysis, they do not find evidence that this is so. Instead, they find little explanation for FAR stringencies across China, aside from the fact that places with ancient historical sites are stricter. Their results seem to indicate that FAR limits are based on the preferences of city officials rather than on underlying economic principles.

Land Values in the United States

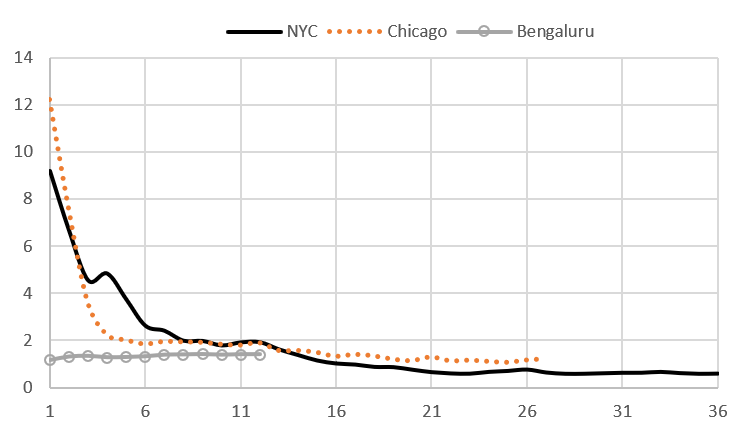

Brueckner and his co-author, Ruchi Singh (2020), study land values and FAR stringency across U.S. cities. The lower the average allowable FARs, the lower the land values are likely to be, and hence the greater is the “gap” between what residents want and what developers can supply. In particular, they investigate how FAR regulations impact land prices in New York, Chicago, Washington DC, Boston, and San Francisco from 2000 to 2018.

Their analysis allows them to estimate the gaps. They find that New York City is supplying only about 70-77% of the demand. For Washington DC, this number is between 60 to 72%, which makes sense given that DC also has height caps. Boston is supplying around 78 to 83%. And Chicago is at 92 to 94%.

Interestingly, they find that San Francisco’s gap is only between 90 to 93% of what the market wants. Their findings are likely being driven by the relative stringency in each city’s central business district. The demand to live and work in Manhattan is quite strong.[4] Unlike San Francisco’s business district, which “competes” with Silicon Valley, Manhattan has few direct local competitors for its financial and tech services. Similarly for Chicago and Boston.

What Would you Do?

I asked Professor Brueckner to summarize the findings from his body of work. He indicates that, in short, city planners should be careful for what they wish for. He says,

FAR limits reduce housing supply, raise prices and lead to longer commutes. If there are no good reasons for the restrictions, such as better neighborhood ambience, the outcome is a loss for city residents.

As Brueckner’s research shows, the path to getting things right begins with measuring the costs of excessive restrictions. Not going too far with FAR stringency can help a city reduce the negative impacts of density, without eliminating or reducing its benefits. And now, with this in mind, what have you decided to do in your role as Chief Building Heights Planner? If you want to take a look at my planning ideas, you’ll have to stay tuned for a future post on the subject.

—

[1] You will be part of a team that is developing other rules, including building codes, requirements for health and safety, as well as regulations about land uses. Your decisions will be made in consultation with them.

[2] “Plot ratio,” “floor space ratio,” “floor space index,” “gross plot ratio,” and “site ratio” are other terms also used to designate the FAR.

[3] To the best of my knowledge, there is little research on how residents feel about different kinds of architecture, building shapes and arrangements, and their willingness to pay to be in these neighborhoods. Architects and planners, who have strong feelings about what is right and good, are usually the ones, along with politicians, writing the rules about building heights and densities. There is research to support the notion that walkability and mixed uses are good for residents’ well-being. These findings suggest that there is too much automobile usage and too many zoning restrictions. Good policies can reverse be undone by them as well.

[4] A similar 2019 study for New York City was performed by Brueckner’s student, Byunggeor Moon. Here Moon did the analysis with properties bought to be torn down, rather than vacant lots as in Brueckner and Ruchi (2020). Moon’s findings compare similarly to those of Brueckner and Ruchi.

The presumption in the article that Density is directly related with Higher FAR is not entirely true. In fact sometime it is the other way around If you compare per capita floor area in lower income residential areas and higher income residential areas. Even with lower FAR the population density is high in Slums or old City areas.

I agree with this point in general. But population density is determined by multiple things besides just the allowable FAR. Income and transportation access is also a problem. So in cities with a large low-income population and bad transportation networks, people will live densely. The FAR only limits the total building space, not how that space is carved up among different households. An apartment building with FAR one could have one family or 20, depending on how they subdivide the space. But throughout history, restrictive FARs were used in the hopes of limiting density. But without taking into account things like access to jobs and transportation mobility, those FAR restrictions can backfire.

Thanks for your comment.

-JB

What are your thoughts about eliminating FAR and density caps completely and replace with regulating building heights, building to building setbacks, on-site open space and maximum parking ratios.

Your question has motivated me think about writing a long answer in the form of a new blog post (however, given my current schedule, it will not be posted for a couple of months). My short answer is:

All zoning codes need to have some flexibility to reflect the demand conditions. When zoning regulations of any kind restrict supply too severely they cause prices to go up and increase the affordability problem.

Flexible zoning codes, however, must be paired with plans to upgrade infrastructure, transportation access, parks, educational facilities, etc, if population increases in a neighborhood.

Capping as a policy, in general, is not a policy that allows for flexibility. If there are caps, it makes the “squeeze” between demand and supply greater and then causes more sprawl and congestion.

By and large, I favor set backs based on street widths or “platform” style in highrise neighborhoods, with continuous street walls. Cities like New York are great at providing parks and open space, and so good policy should create new local parks as a function of population growth.

Lastly, I highly recommend Alain Bertaud’s book, “Order without Design.”