Jason M. Barr March 18, 2024

[Note this post is a part of a series on the history of New York’s grid plan. The entire series can be found here.]

Manhattan 1.0

In 1811, the Street Plan Commissioners produced Manhattan’s grid system. Accompanying their map was a brief set of remarks highlighting their decisions. First, they felt a gridiron plan was best because “straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in.”

Second, they believed there was little need for abundant park space because “those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan island render its situation, in regard to health and pleasure as well as to the convenience of commerce, peculiarly felicitous.” Lastly, they decided to stop at 155th Street because “it is improbable that (for centuries to come) the grounds north of Harlem Flat will be covered with houses.”

Manhattan 2.0

Ironically, one man in the second half of the 19th century would be largely responsible for “reversing” or adjusting those choices in Manhattan and beyond. That man was Andrew Haswell Green, one of New York’s most important but least-known leaders who helped to shape, both literally and figuratively, the path that New York would take in the second half of the 19th century.

Green would oversee the creation and expansion of Central Park from 1857 to 1870. He would also be responsible for laying out a street plan north of 155th Street and would help influence street planning and parks in the Bronx. In essence, he was Grid Commissioner 2.0, altering New York’s landscape beyond the repetitive street layout.

Just as importantly, he was a forceful advocate for the city’s physical expansion, which led to New York first annexing the Bronx and then, in 1898, to the final joining with Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island to create the City of Greater New York. The new municipality would have the power to plan and layout streets and coordinate transportation and infrastructure, enabling Gotham to become one of the world’s greatest cities.

Andrew Haswell Green

Green was born in 1820 on the family farmstead near Worcester, Massachusetts. He moved to New York when he was 15 and eventually studied law under the tutelage of Samuel Tilden, a well-known lawyer and politician. After a successful law practice, Green moved into government service, emerging as one of New York’s most influential civic leaders. Though he was a Democrat, he was opposed to the corruption and excesses of the Tammany Hall wing. His sweeping plans gained wide support from Albany’s republicans and city reformers eager to check Tammany’s corruption and provincialism.

Green was known as an honest and capable administrator. If anything, he had a reputation for extreme frugality, as he strongly felt that the government should administer public works with the least amount of expenditure. New York City historian Thomas Kesner describes him as,

Self-righteous in the extreme, he kept few friends while gaining many admirers for his versatile skills in municipal planning and his undoubted integrity. Severe, demanding, caustic in debate, with a reputation for cantankerousness, he could be very persuasive in person and even more so in his writing, which had greatly improved over the years.

His first foray into public service was as a member of the Board of Education from 1855 to 1860, becoming its president in 1857. Then, he was drafted into the state-appointed Central Park Commission in 1857, which was charged with creating a green oasis on Manhattan Island.

As Green biographer George Mazaraki, writes,

Indeed, for the twenty years between 1857 and 1877, he would be identified with almost every major project aimed at municipal improvement, ranging from Central Park and Brooklyn Bridge to New York’s annexation of a portion of lower Westchester and the reform of municipal administrative practices.

In 1870, Green moved into citywide government as comptroller and was instrumental in rehabilitating the City’s budget after years of graft, corruption, and a general feeding at the public trough during the reign of Tammany leader, William “Boss” Tweed.

The Rise of Central Park

After 1811, as the grid began to “eat” Manhattan, it became clear to many that the street plan was a juggernaut, devouring the natural world in its path and ignoring many of Manhattan’s topological and ecological features. Streams were buried, hills were leveled, marshes drained, and forests cut down.

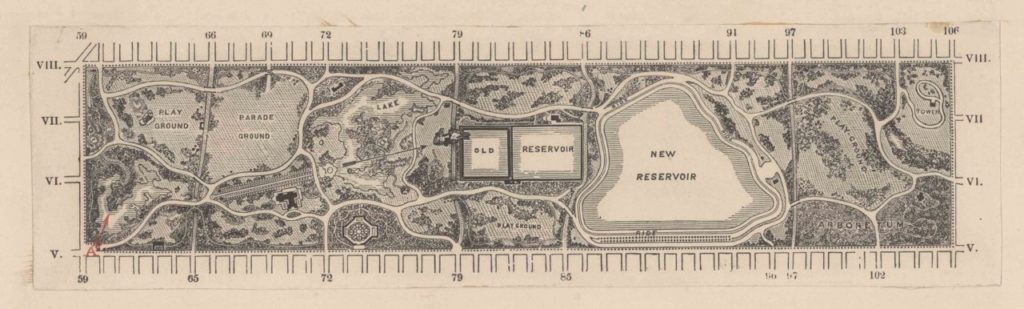

As a result, by the late 1840s, there was a movement for Manhattan to have a large park. In 1853, New York State passed a law to take 778 acres of land through eminent domain. In 1857, the state legislature established a Central Park Board of Commissioners to begin the planning process.

The Zeitgeist

Having a large park was seen as vital for many reasons. The first, of course, was to undo the omissions of the 1811 plan. But just as important was the social and economic context. Urban reformers witnessed the poverty and dislocations in neighborhoods like Five Points and the Bowery and felt the masses needed a becalming natural outlet.

In Europe, revolutionary activity was in the air. American reformers worried that without some palliative balms, the American apple cart could be, so to speak, easily turned over. The rich also wanted the pleasure grounds for their Sunday strolls and horse races. Collectively, the wealthy, the propertied interests who wanted to reap the benefits of higher land values, advocates for the poor, and urban reformers united to turn the movement into a reality.

A Green Park

Green was initially appointed a board member but then was made president and treasurer in 1858. In 1859, he became the park’s comptroller, a newly created position that allowed Green to be, effectively, the Central Park CEO. Under Green’s leadership, the Commission surveyed and assessed 34,000 lots owned by 561 property owners, 20% of which were owned by three families. The Commission paid $5 million for the parcels, three times what leaders assumed the park would cost. One-third of the park’s construction cost was paid for by abutting property owners through special tax assessments.

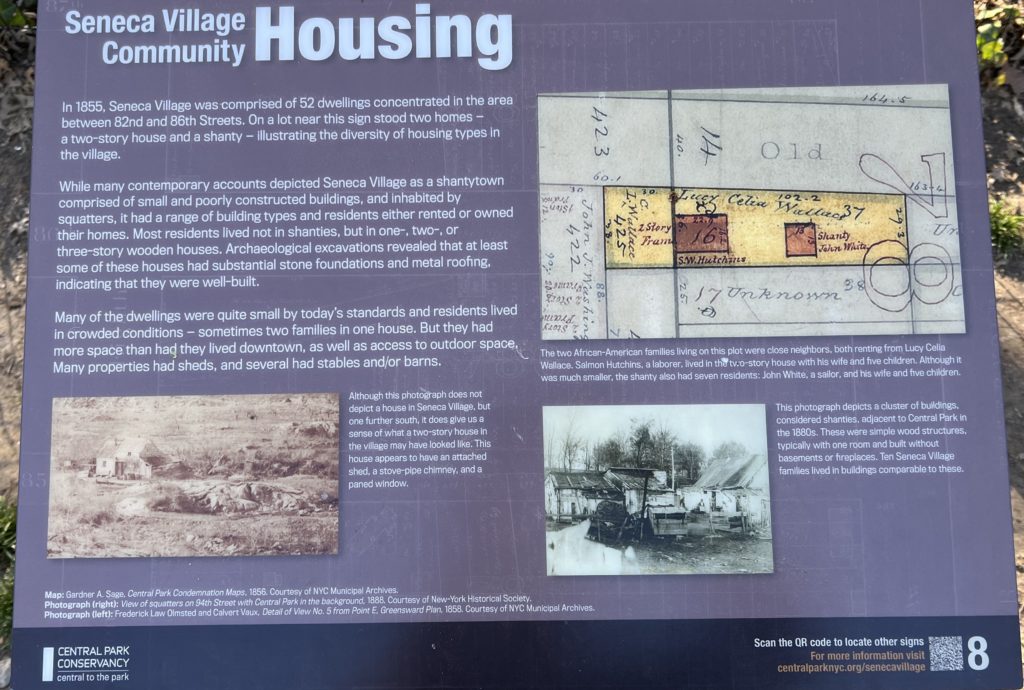

Squatters had to be removed. As historians Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace recount, “The sixteen hundred or so Irish, German, and blacks who lived on the land—dismissed and disparaged as ‘vagabonds and scoundrels’—were evicted by 1857.” Today, historians are recovering these residents’ forgotten histories.

For example, the land between 82nd and 85th Streets on the west side of the park was the home to Seneca Village, which was a successful lower-income cluster of dwellings far north of the city proper. One resident was Andrew Williams, the first African American to purchase land in the area in 1825. He lived in the village with his family and other black residents.

Green and Greensward

To find a design, the Central Park Commissioners sponsored a competition. Green was a leading voice that led to the choice of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s design. As Mazaraki writes, “[T]heir Greensward Plan proposed a reformer’s vision—a space designed to school both patrician and plebeian cultures by transmitting, almost subliminally, civilized values and a ‘harmonizing and refining influence.’”

No commercial activity was allowed inside its boundaries. Four transverse roads would be built below grade to allow the park to remain seamless from south to north. Within its acreage, there would be a wide range of uses, from promenades to wooded glens and hills to open fields.

Olmsted was also chosen as the park superintendent to oversee the implementation of his plan. Olmsted, whose vision was expansive and expensive, would frequently butt heads with Green, who sought to keep those expenses in check. They would fight and argue, but the finished product was a masterpiece.

As Kessner writes,

The creation of Central Park formed Green’s apprenticeship in city planning. He mastered its every detail as well as the larger vision. For the ten years that he presided over the Central Park Commission, Green set aside his other work to give the project his full attention. He was the commission’s workhorse and its most forceful member. “No one but Green knows,” Olmsted wrote of his sometime adversary, “or will take the trouble to inform himself, of the facts bearing on any question of policy sufficiently to argue on its effectuality….Not a dollar, not a cent, is got from under his paw,” Olmsted would complain regarding his prickly nemesis, “that was not wet with his blood & sweat.”

However, Green was not such a spendthrift that he was blind to opportunities as they arose. He advocated for expanding the park’s northern edge when he saw that the Commissioners could buy the land from 106th to 110th Streets before it was developed, thus adding 65 acres. To encourage the arts, Green invited the Metropolitan Museum of Art to build on the grounds. And Green was instrumental in creating the zoo.

Beyond the Park

Thanks to the success of Central Park—an example par excellence of a well-executed public work with a sublime design—the Central Park Commission was given control of planning outside of the park. In 1858, Green made the case for the opening, widening, and improving of the streets and avenues bounding the park in parallel to the park’s opening. This was particularly important because the northern part of the city was only at 42nd Street, with only a single paved road—Seventh Avenue—above it. The Park Commission opened Seventh Avenue from 110th Street to Harlem River, along with Central Park East and West.

The Park Commission was also permitted to make changes in the widths, directions, and grades of streets on the Upper West Side. It could also redesign the area entirely if so desired. In an 1865 report, Green expressed his doubts about the grid plan:

It is not too much to say, that [the 1811 Commissioners] carried to an extreme, a system well enough adapted to the tolerably level ground of the lower part of the city. They found something similar to it already existing in the neighborhood of the Seventh Ward and they fixed it upon irregular and precipitous portions of the island to which it was not at all adapted. The Commissioners failed to discriminate between those localities where their plan was fit, and those to which its features were destructive, both in point of expense and convenience.

The Upper West Side

Despite his desire to do away with the grid plan on the rocky and hilly Upper West Side, his hands were tied. Though the area was composed of little more than hamlets separated by few country seats and small farms, the streets and blocks had already been marked for creation, and to undo what the grid plan established would have been too disruptive.

However, there remained some opportunities. Where Broadway curved around the park’s western edge, Green created a large oval, named Columbus Circle in 1892. Broadway was continued north to the end of the island and beyond. Green and the Commission also saw to Riverside Park’s creation along Manhattan’s western edge. The plan also included the windy Riverside Drive, running from 72nd to 129th Streets, and later extended to 158th Street

Olmsted and Vaux were drafted to create the plan. Riverside Park too is a masterful work, a narrow green oasis along the Hudson River, with multiple levels that make it feel more spacious than it is. Along Riverside Drive is a paved promenade. Below them are steep wooded slopes, and meandering paths. Below that are more promenades and public spaces. In the 1930s, the park was extended by Robert Moses to the shoreline, after the New York Central railroad tracks were covered.

North of 155th Street

By the mid-19th century, it was clear that the 1811 Grid Plan Commissioner’s projections that the land north of 155th Street would not be opened for a century was a bit off the mark. (They did not foresee the invention of rail-based mass transit, including railroads, streetcars, and elevated lines.) As a result, in 1851, the Common Council asked the street commissioner to create a plan for upper Manhattan. But there was no money allocated, and nothing happened.

Next, in 1860, a state law empowered a commission to formulate a street plan—especially to create something different than the grid plan. Olmstead and Vaux were hired as the landscape architects. However, in 1863, the Commission rejected their mandate and advocated for the continuation of the regular rectangular blocs.

The public’s outrage and property owners’ desire for better planning led to the Central Park Commission being awarded in 1865 the right to create a street plan north of 155th Street. The dramatic elevation changes, however, made it economically unfeasible to level the area. As Mazaraki writes,

The area’s rough and varied topography made any extension of the 1811 gridiron street pattern impossible. Elevated and exceedingly rocky in some parts, while low-lying in others, the expense of establishing a uniform grade would have been financially prohibitive even if technically possible.

A Thorough Review

Unlike the 1807 Commissioners, Green undertook a more detailed review of the topology and geographic and environmental conditions of the northern section. In 1868, he called for gridding areas in the flat valleys. However, looking at the highlands on the west side, Green questioned the cost of blasting cross streets through the rocks and the risk of making the grades so steep that the horse-drawn wagons would not be able to use the roads. As Mazaraki concludes,

Expecting that future traffic would tend to be longitudinal (north-south) he saw no need for numerous cross streets or the forcing of city lots into high ground. In this respect, Green made a major mistake. Not north-south, but east-west traffic would come to predominate and a series of lateral avenues would have served the region better.

The Commission planned three major north-south roads. It kept the historic Kingsbridge Road (which became Broadway) and created St. Nicholas Avenue out of what was formerly known as Harlem Lane. Green also proposed an eastern road that would run along the shoreline of the Harlem River. For this, a new bulkhead line was required. Where avenues such as Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh intersected with each other or with the shore drive to form small triangular plots, Green called for a series of small parks.

Green’s interest in parks also led him to preserve the views of the Hudson River from the hills of northern Manhattan. From this wish emerged an eight-acre park at Fort Washington Point, forming the kernel of today’s Fort Tryon Park. Later, between 1915 and the early 1940s, the City purchased the land that makes up the forested Inwood Hill Park at the northern tip.

In the end, Green created a hybrid plan. In the lowlands, the grid plan was continued, while in the highlands, the roads and blocks followed the land’s natural contours. However, unlike Manhattan below 155th Street, where all blocks had an east-west orientation, the northern plan has blocks with various directions that fit more naturally into the terrain.

Beyond Manhattan

One of the of the great ironies of the 1811 Grid Plan was that its call for leveling and paving nearly all of the island led to a strong pushback. New York would get its nature yet. Central Park, though thoroughly sculpted and arranged, is one of the world’s greatest green spaces. And just importantly, Manhattan’s growing density would generate a cry for more open spaces elsewhere. In the next post, we turn to the story of how the Bronx became the borough of parks, zoos, and botanical gardens.

Continue reading the rest of the series on Manhattan’s grid plan here.

Leave a Reply