Jason M. Barr June 30, 2025

What is the best way to keep housing affordable?

Well, to the former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio (2014-2021), the obvious answer was to restrict landlords’ ability to raise rents. Given the severe housing shortage, building owners are seemingly in a position to gouge those who can least afford it; therefore, the conventional wisdom is that the best policy response is to prohibit rent increases.

The culmination of de Blasio’s affordability agenda was the 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA), which provided “the strongest protections for New York’s tenants in decades.” When passed, de Blasio announced the new rules with great fanfare as a victory for the low-income resident.

The law was intended to help renters. However, it is, in fact, harming them. HSTPA is driving the slow but inexorable decay of the low-income housing stock.

The 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA)

Among its long list of tenant protections, the law repeals several types of rent increases. Landlords can no longer decontrol units that are either high-rent or have high-income renters. The law also ended a vacancy bonus, which allowed landlords of rent-regulated units to collect an automatic rent increase of up to 20% upon vacancy. And just as importantly, only 2% of any major capital improvements can be passed along to tenants through higher rents. In other words, building owners must absorb the costs of upgrading their buildings. And, of course, rent-stabilized units must still have their rents increased by no more than that set by the Rent Guidelines Board.

Sounds great, right? What’s not to love now that the government prevents tenants from getting massive rent increases?

Well, the answer is: Be careful what you wish for. By limiting rental income while raising costs, HSTPA is squeezing landlords on both ends, making it particularly challenging to make ends meet in this high inflationary environment.

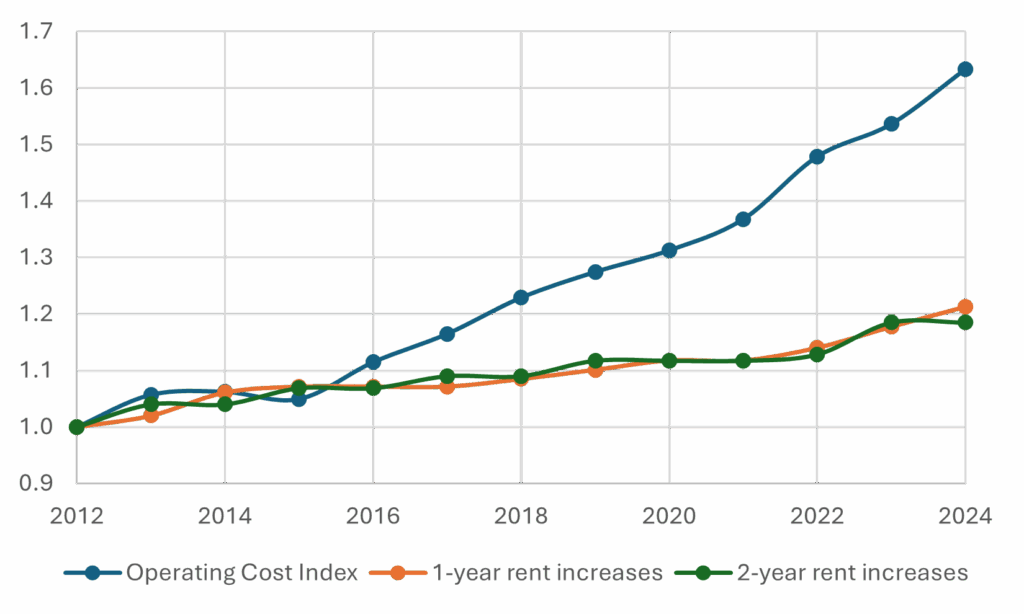

One way to see this is to examine the annual increase in allowable rents (limited by the Rent Stabilized Guidelines Board) in relation to the operating costs of apartment buildings. From 2012 to 2024, rents, through the allowable RGB increases, have risen by about 20%. At the same time, the cost of operating apartment buildings has increased by about 63%. In the past, some of these additional costs could have been offset by rent increases on empty units or those that were decontrolled. But no longer.

The Impact of the Law on Building Maintenance

Given the “big squeeze,” there are only a few options left for building owners. One such option is to defer maintenance and upkeep. Although there’s evidence that owners are falling into the red and that buildings are becoming close to worthlessness from an financial perspective, the question remains: Is HSTPA driving the deterioration in New York’s affordable housing stock?

Class C Violations

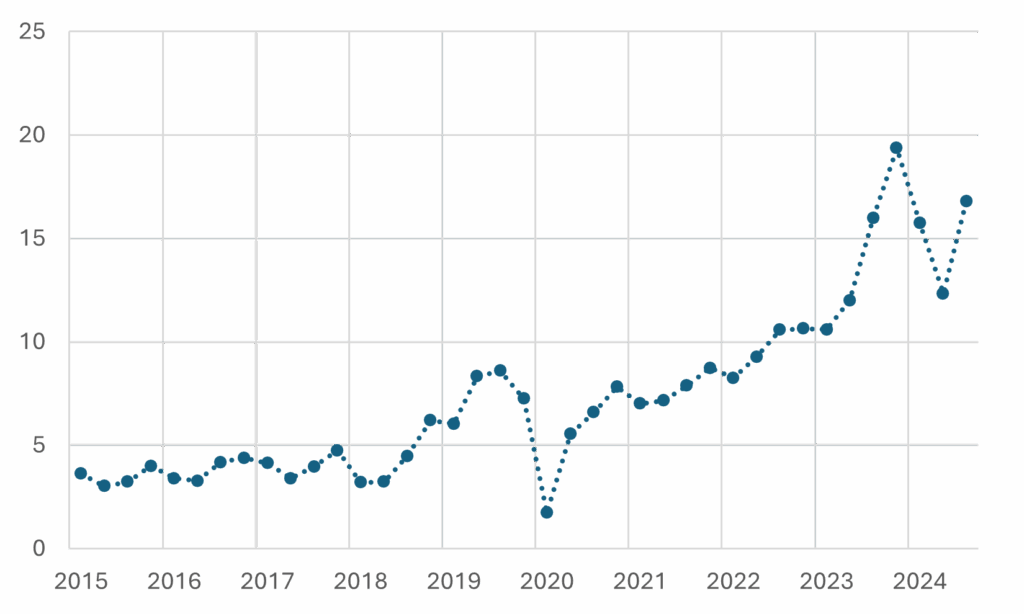

To investigate this question, we can look at building violations, particularly the worst and most harmful kind—those classified as Class C, which present “immediately hazardous” conditions. They include inadequate (or no) heat in the winter, rodents in the building, peeling lead paint in homes with small children, a lack of hot water, or the presence of mold or mildew. By law, property owners must correct these issues within 24 hours of receiving a violation notice.

Part of the problem, however, is trying to infer how much is coming from HSTPA versus profit loss from inflation, since the two things hit New York’s at around the same time. Either way, the data indicate a significant increase in Class C violations beginning in 2019.

Treatment and Control

To investigate if the law had a causal impact on building maintenance, we need to compare rent-stabilized buildings to a benchmark group that was not impacted by the law, while controlling for trends driven by inflation and other factors. To do this, I used two treatment-control groups, respectively. (Data sources and results can be found here.)

The first comparison is between apartment buildings that had at least one rent-stabilized unit in 2017 versus those that did not. The other is to compare rent-stabilized buildings to all other types of multifamily buildings, including condo and coop buildings.[1]

The Difference in the Difference

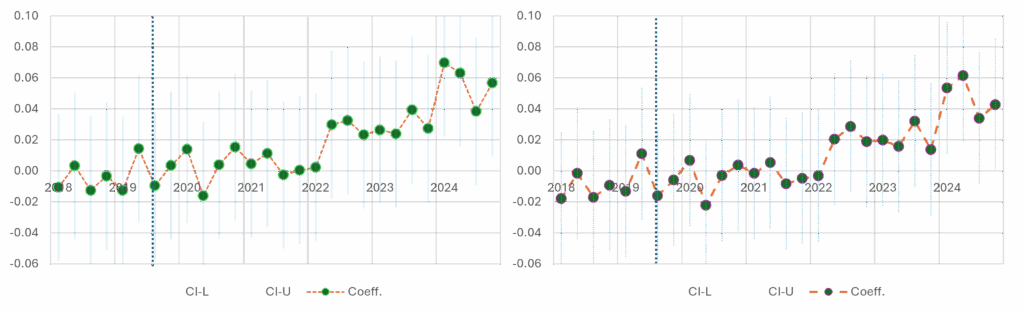

The figures below show the relative difference in Class C violations in quarterly increments from January 2018 to December 2024 (after controlling for a host of building, location, and general trends—more details here). The left figure compares the differences in Class C violations between rent-stabilized and non-rent-stabilized rental buildings in New York City.

The results show that, prior to 2019, there was no discernible difference in the trends. That is, the difference in violations between the two types of buildings were the same. However, after 2019, we observe a spike upwards—particularly from 2022 onward, which strongly suggests that HSTPA is incentivizing rent-stabilized building owners to under-maintain their buildings. A similar result emerges for rent-stabilized buildings as compared to all multifamily buildings, shown in the right figure (also note that I also controlled for trends in rental building violations in general).

Based on my calculations, before 2019, the probability that a multifamily property would have at least one Class C Violation each quarter was about 4%. After 2019, it increased to approximately 7-8%; from 2022 onward, it rose to the 15-20% range. My regression results suggest that approximately 30% of the rise in Class C violations since 2022 can be attributed to HSTPA, with the remainder resulting from operating cost inflation relative to allowable rent increases (and possibly higher interest rates).

Policy Responses

Policy decisions regarding rents have been largely driven by the fact that two out of our three residents in New York City are renters. Given their supermajority in the housing policy space, they are more likely to score victories for their pro-tenant agendas, regardless of the impacts on or incentives to building owners.

Nonetheless, improving affordability—along with building quality and maintenance—is one of the most critical issues facing New Yorkers. But the cure for affordability is not to pit tenants against their landlords. Instead, the key is to focus on adding new housing supply—particularly in the missing middle.

If housing were so abundant that apartment vacancy rates consistently exceed 5% and thus ended the “housing emergency,” rent stabilization and HSTPA will be unnecessary. When landlords must compete for tenants, watch what happens: rents will moderate or fall, and buildings will remain well-maintained.

The reason why rent regulations have remained so important as a housing policy tool is that New York builds so few units each year (in the suburbs, it’s even worse). Recent upzonings, as part of the City of Yes—while an important first step—are likely to have only a moderate impact on supply. The City must be more aggressive in adding housing in neighborhoods where it’s needed the most—in the lower-income neighborhoods outside Manhattan’s core and in the suburban neighborhoods where one- and two-family homes dominate.

I have written on this topic before, so let me summarize some of the necessary policies:

Vacancy Targeting in Low-income Neighborhoods

If low vacancy is the driver of unaffordability, the government should develop strategies to increase supply (and vacancy) in the neighborhoods either through generous upzoning and subsidies, or by issuing ground leases to low- and middle-income housing developers on large lots purchased by the City.

Transit-oriented Development

Properties near commuter rail and subway lines—both within and outside the city—should be greatly upzoned to allow for apartment buildings. The upzoning need not be for high-rises—low- and medium-rise buildings can do the trick.

ADUs and Subdivisions

Homeowners in suburban neighborhoods throughout the region should be encouraged to build an extra unit or two on their properties, such as by converting a garage into a studio apartment or by subdividing a home.

Master Planning

Housing supply and affordability, transportation, schools and services, and parks are interconnected. Today, city governance deals with each of these virtually independently—it’s time that the City plans to create all these upgrades simultaneously.

Don’t Punish, Incentivize

The solution to the affordability crisis is not to punish landlords; instead, it’s to encourage the construction of new housing. New York has always been a city of strivers. The Statue of Liberty stands in the harbor as a symbol of Gotham’s openness. To honor the spirit of Lady Liberty, it’s time to build more housing, and to stop implementing policies that are analogous to spitting into the wind.

Thanks very much to Cristina Scofield, whose research on the Mitchell Lama housing and Class C violations was helpful in inspiring this blog post.

—

[1] Data on rent-stabilized buildings, however, is not very detailed. Every year, the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB) lists buildings that have at least one rent-stabilized unit. The purpose of the database is to assist prospective tenants in their search for an apartment. But beyond that, we don’t know how much income landlords have from rent-stabilized units or what fraction of the building is rent-stabilized.

Great post Jason. Perhaps send to the attention to our probable new mayor.

Thanks! You’re right- I should do that.

Only wish Mamdani read this!