Jason M. Barr December 17, 2018

Note this is Part I of a series on the economics of skyscrapers. The rest of the series can be read here.

Clark and Kingston

In 1930, W. C. Clark and J. L. Kingston (CK), an economist and architect, respectively, published a book called, The Skyscraper: A Study in the Economic Height of a Modern Office Buildings. In this work, they act as a hypothetical developer of a Manhattan office skyscraper. Their aim was to determine a height for the structure which maximized the return, given the rents, and the costs of land and construction.

In fined-grained detail, they laid out the various elements of erecting such a building, including floor plans, and the all the different types of costs a builder must pay, from bricks, to elevators, to steel. For their analysis, they chose a large lot across the street from Grand Central Station, in the heart of Manhattan’s midtown business district.

The point of this exercise was to demonstrate that the supertall towers rising in Manhattan during the late 1920s were not “freak” buildings, but rather, were based on reasonable economic foundations.[1] They showed that when one did all of the accounting—comparing the income to the costs—the height that maximized the return was 63 stories. (Ironically, this is not that much different than today. One Vanderbilt, an office building currently under construction across the street from Clark and Kingston’s hypothetical lot, will rise 58 stories.)

The Skyscraper: A Study in the Economic Height of a Modern Office Buildings (1930).

Economic Height

In their book, they present a definition of what they called the Economic Height of the building, based on the writings of the engineer, J. Rowland Bibbins; and one that is still reasonable:

The true economic height of a structure is that height which will secure the maximum ultimate return on total investment (including land) within the reasonable useful life of the structure under appropriate conditions of architectural design, efficiency of layout, light and air, ‘neighborly conduct’, street approaches and utility services. (pps. 8-9)

Economic Height provides a useful guide (though not the only one) for understanding why skyscrapers get built, since this height is determined by the best balance between the revenues and costs. In general, going taller will generate more income, but will also add to the expense. In modern economics terminology, the economic, or profit maximizing, height is one where at the highest floor, the additional or marginal revenue from that floor just equals the marginal or additional cost to providing it. If built one floor higher, the cost of adding the floor will be greater than the revenue and will not be worth it. If less than that height, money is “left on the table,” since adding a floor would produce more income than it would cost to produce it.

It’s worth stressing is that a developer builds this optimal height to earn a profit. People and companies are willing to pay the high prices because of the needs they fulfill and the benefits they provide. Thus, Economic Height is a response to the demand; not the other way around.

Land Values and Building Height

As CK also demonstrate, there is a direct relationship between the cost of acquiring the land and the return on investment from a taller building. We can think of developers as a type of urban farmer; the more it costs to acquire a lot, the more they must intensely develop the land in order to receive enough income to compensate for the high cost of the location. Thus, around the world, we observe taller buildings in places that have higher land values.

Given this notion of Economic Height as a benchmark, we can then say that any building that is taller than this can be considered economically “too tall” in that it is higher than it “ought to be” for pure economic gain; and hence produces lower profits than a shorter building. The difference between the actual and Economic Height is what I call Symbolic Height.

Height in the 21st Century

Even though Clark and Kingston published their book nearly 90 years ago, the question of whether buildings are economically too tall remains as relevant today as it did during the Roaring Twenties. To look at the Economic Height at one location, Clark and Kingston

(funded by the American Institute of Steel Construction) hired a stable of expert consultants to help them analyze the problem. The ability of someone like myself to determine the Economic Height for even one building must come from publicly available data; and it’s virtually impossible to calculate it for many structures. However, we can make statistical inferences if we collect a large enough data set.

Skyscrapers around the World

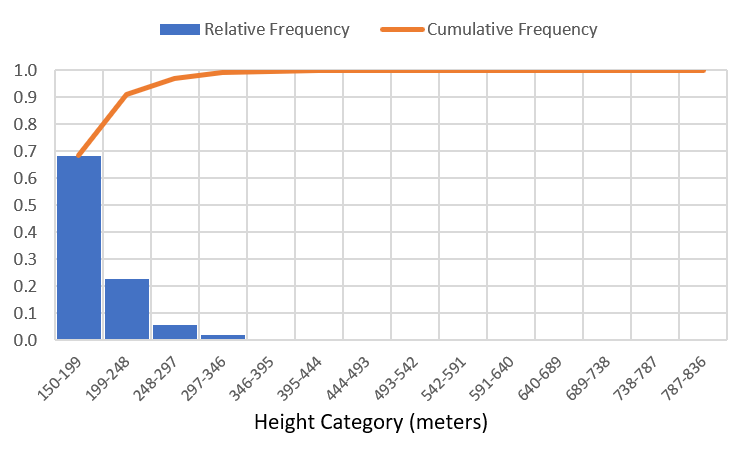

For convenience, let’s define a skyscraper as a building that is 150 meters (38 floors, on average) or taller (and just focus on 1960 to 2017). Now imagine that you were a giant and could “harvest” all the world’ skyscrapers and put them into a jumbo pile—like a child might make a pile of sticks of various lengths. Now in our little game, we pick up each skyscraper (stick) and measure its height. Then we place it in one of several bins or buckets. The first bucket will contain buildings that range from 150 to 199 meters. The second contains buildings 200 to 248 and so on. The last bucket ranges from 788 to 836 meters, and which contains the Burj Khalifa at 0.828 km tall.

Which bucket has the most buildings? And what does this suggest? According to the CTBUH, there were 4,162 skyscrapers built between 1960 and 2017. It turns out that the vast majority of tall buildings are less than 200 meters (68.3%). Only 23 are 400 meters or taller. Statistically speaking if you were to randomly pick a skyscraper constructed since 1960, the probability that you would select a building greater than 400 meters is about one-half of one percent. The vast majority of buildings are “regular-talls” (under 50 stories); while the number of “super-talls” is minuscule, in comparison. The super-giants, while most visible from media accounts and their appearances in skylines, only make up a tiny, tiny fraction of the world’s skyscrapers.

The Drivers of Economic Height

The evidence suggests that the bulk of the world’s skyscrapers are consistent with the notion of Economic Height. This is not to say that all skyscrapers reflect the best balance between the costs and benefits, but it is to say that the majority of the world’s skyscrapers have a strong economic rational, in that they are catering to a demand for building height. So what are the key economic drivers of skyscrapers?

Economic Growth

Most important is the process of economic growth and urbanization. The more economic activity there is in a city or region the more central locations become vital because people and business need to cluster near each other to more efficiently produce the goods and services that our modern economies require. The skyscraper shrinks space so that hundreds if not thousands of people can be at the same geographic coordinates at the same time. The tremendous demand to be in the central city creates a kind of “battle for place”—if more people want to be at a central location than can be accommodated, the price of that location rises. As land values rise, so does Economic Height, and skyscrapers rise as a result.

The ability of a country to build skyscrapers is directly related to the size of its economy. Once a country hits a threshold, in terms of its gross domestic product, there is then a very strong relationship between both the number of skyscrapers it has and the height of its tallest building. Arguably the greatest predictor of the height a country’s tallest building is the number of highrise buildings it has; and the greatest predictor of the number of tall buildings is the size of its economy.

The Cost of Construction

Today’s skyscraper technology is the result of a 130-year learning curve. Innovations in design, materials, and engineering, combined with lower labor costs in the developing world, make them attractive investments. While there has been no systematic research on the evolution of (inflation-adjusted) marginal or per-floor costs over the entire 20th and early 21st centuries, the evidence we do have suggests that these costs have been declining.

In Manhattan during the early years of skyscraper construction, between 1900 and 1920, I estimate that the marginal or additional cost of adding another floor averaged about 7%; between 1921 and 1931 this cost dropped to about 3%. In other words, in New York City, during the Roaring Twenties it was getting much cheaper to add extra floors. Builders were responding accordingly by adding more floors; this can explain, in part, the building boom of the era.

Costs around the World

Fast forwarding to the 21st century, it’s instructive to look at a few recent examples. In January 2010, the world’s tallest building, the Burj Kalifa (163 stories) was completed. Its total construction costs was only $1.5 billion, or $9 million per floor. The comparatively expensive 128-floor Shanghai Tower, completed in 2015, cost $2.4 billion, or $18 million per floor. Contrast that with the 2009 58-story Bank of America Tower in Manhattan, which cost $1.76 billion, or $37 million per floor. While a few examples do not prove anything, it does illustrate that Asian countries can pay less to get more, in terms of building height. In New York and other U.S. cities, it seems to be the case that the cost reductions from technological progress are offset by the rising cost of labor and materials. In Asia, rapid economic growth, and intense urbanization, combined with lower building costs and an eagerness to employ innovations in design and construction, are driving building booms in their cities.

Are Megatall Buildings Good or Bad?

But what about the megatall giants like the Burj Khalifa, the Shanghai Tower, or the Taipei 101? They must be wasteful projects, with little economic rational, right? I would argue that the answer is not so clear, and that maybe we should not be so hasty to judge. Stay tuned.

Continue reading. The rest of the series can be read here.

—

[1] I would add a few caveats to their conclusion. First, they only analyze one hypothetical building on a very large lot of land in the center of midtown. So their ability to generalize is some what limited. And, second, to the extent that land values and office rents might have been inflated because of over-optimism and an overheated stock market in the late-1920s, means that their resultant height might have been too high.

[…] this is Part IV of a series on the economics of skyscrapers. Part I can be read here, Part II here, and Part III […]