Jason M. Barr January 20, 2021

You’re So Vain?

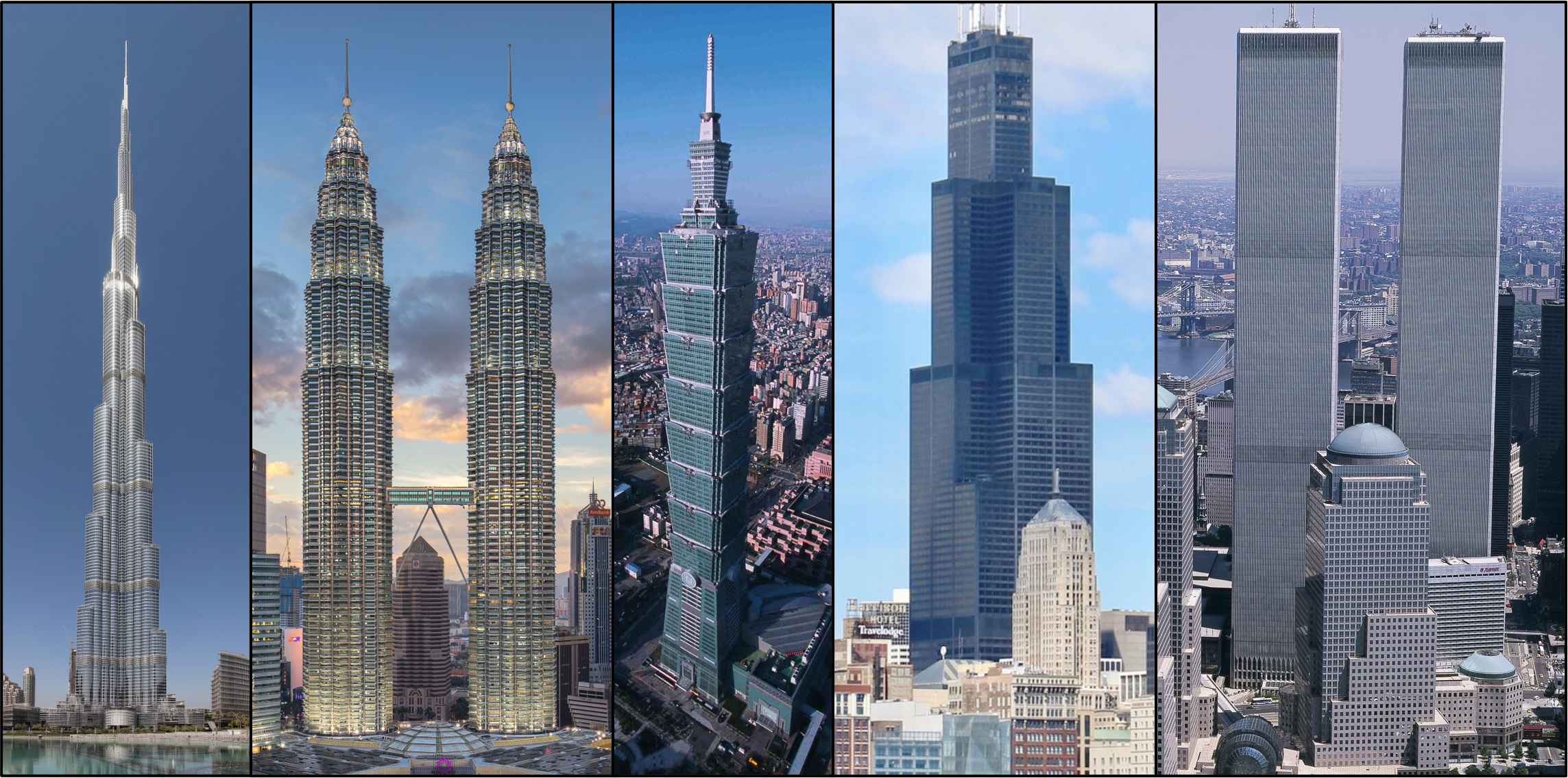

On January 4, 2010, the Burj Khalifa officially opened its doors. At 828 meters (2,717 feet) it became the world’s tallest building by a long shot. It overtook the previously tallest building, the Taipei 101, by 302 meters (991 feet). The only rub: Much of Burj is empty space—the top third is a 243-meter (797-foot) spire—where no human will likely ever work or live.

The difference between the actual or architectural height (excluding TV and radio antennae) and the highest occupied floor is what the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) has dubbed “Vanity Height.” They originally coined the term, with tongue in cheek, because some developers—presumably—have added a decorative element simply so they can brag about having a taller building. For the CTBUH, the de facto arbiter of official building heights, these elements create a conundrum.

The most famous recent examples of Vanity Height are the Petronas Towers (1998) and One World Trade Center (2014). When completed, the Petronas Towers took over the title as the world’s tallest building (until 2004) because of its spire. The highest occupied floor remains well-below the previous record holder’s top floor, the Willis (Sears) Tower (1974). To many, it seemed that to beat the record, you simply build a tall skyscraper, attach a glorified pole, and declare victory.

Similarly, One World Trade Center, in New York, is only the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere because of its 154-meter (505-foot) spire, which looks more like an antenna than an artistic statement. Its sole purpose, it appears, is to allow the skyscraper to rise 10 1,776 feet (541 meters), as a symbolic gesture to the birth (and hopefully continuance) of American Democracy.

Space Wasters?

In 2013, the CTUBH published an article discussing so-called Vanity Height. They showed that among a crop of 200-meter or taller buildings, several notable examples had spires or other architectural elements of at least 95 meters (312 feet), comprising 25% or more of their respective total heights. The article tickled the funny bone of the press, who went on a reporting rampage, producing such splashy headlines as, “Space-wasting ‘vanity’ skyscrapers revealed,” and “44 of the world’s 72 tallest buildings are cheating.”

Assumptions

While the 2013 article was meant as a jocular jab at some developers, the phrase has remained in the public sphere because it feeds the belief that skyscraper builders are only concerned about self-glorification and are unconcerned about other mundane things like profitability or urban well-being. The phrase “Vanity Height” implies that all structures with large vertical voids are—by definition—ego-borne. But this belief obscures other reasons for what is happening up top. The drivers and impacts of this extra height are more complicated.

Another implicit assumption is that skyscrapers are getting “vanier”—that builders are adding more of it now than in the past. The phrase fuels the idea that developers in the 21st century are engaged in an arms race to claim the prize. This suggests a degree of dissipative or wasteful competition—that by adding height to stand out, developers are spending resources to satisfy themselves, with no larger benefit to society. To what extent are these assumptions true? The answers will be revealed below when we look at the data.

From “Vanity Height” to “Symbolic Height”

Tall buildings serve many purposes beyond providing space for people to work, live, or play. They also convey information: Big corporations like to be in iconic buildings because they signal something about their business, such as their profitability or trustworthiness. Corporate headquarters are part of the larger need for branding because branding gives a certain level of assurance about what consumers get when they buy a company’s products. More broadly, companies that have national or international ambitions find they need to be in skyscrapers to signal their ability to compete in the global marketplace.

Cities like to have iconic structures because they increase tourism, foreign direct investment, and advertise that the city is a dynamic urban center. Architects, when designing tall buildings, also have multiple goals. They want to not only deliver an iconic structure to their clients but also seek to make their buildings aesthetically pleasing and meaningful. To architects, “Vanity Height” is often shorthand for the design up high.

I asked architect Ro Shroff, of 3MIX, who is involved in several tall building designs around the world, his thoughts:

I generally concur with the notion of Vanity Height, and it has almost become a de rigueur methodology for most architects, to “enhance” the proportions and appearance of the tower, and create some identifiable iconography to differentiate from other skyline cacophonies. This is accomplished either by extending the façade as a screen to hide the rooftop equipment or by creating unoccupiable voids, vertical spires, spiraling crowns or glowing lanterns, not too dissimilar from the design intents of the Empire State and Chrysler Towers in the 1930s.

Then there are developers who may want to have icons for their personal satisfaction or bragging rights. But this leads to an important question: Where do beauty and iconicity end and vanity begin? This is inherently unanswerable. Shroff adds, “Hopefully and presumably, such vanity exercises in ‘irrational exuberance’ by the architects or developers are also countered with fiscal responsibility, maintenance economics, and other checks and balances.”

The Information

The bottom line, however: We cannot say much about so-called Vanity Height by looking at a few buildings. We can cherry-pick and shout-out the ones that appear most egregious. But, as I show below, the data strongly support that relatively few buildings are as bad as we think.

This leads me to propose a new name for this type of height: Rather than Vanity Height, we should call it Symbolic Height, because it is height added to convey information of some kind.[1] This information can be literal, like broadcasting the name or logo of a corporation, or abstract, such as an aesthetic design or sculptural elements.

A Brief History of Symbolic Height

Symbolic Height has a long history and is older than the skyscraper itself. A review of this history demonstrates the multiple purposes that tall structures serve, the different types of information that they broadcast, and the benefits of the voids up high.

We can think of gothic church spires or old city hall clock towers. Sure, their heights were meant to announce the power of the institutions that created them, but they also served other purposes, especially related to telling time—church bells and clocks to telegraph the hour of the day. They also provided locational beacons—in a low-rise city, people could head for the center by moving toward the structure rising in the skyline.

Then there are towers, arches, and obelisks, built with no other purpose in mind than as symbols (with the occasional observation deck thrown it). Despite their “useless” objectives, do we complain that the Eiffel Tower is too tall or that the Washington Monument is a waste of resources?

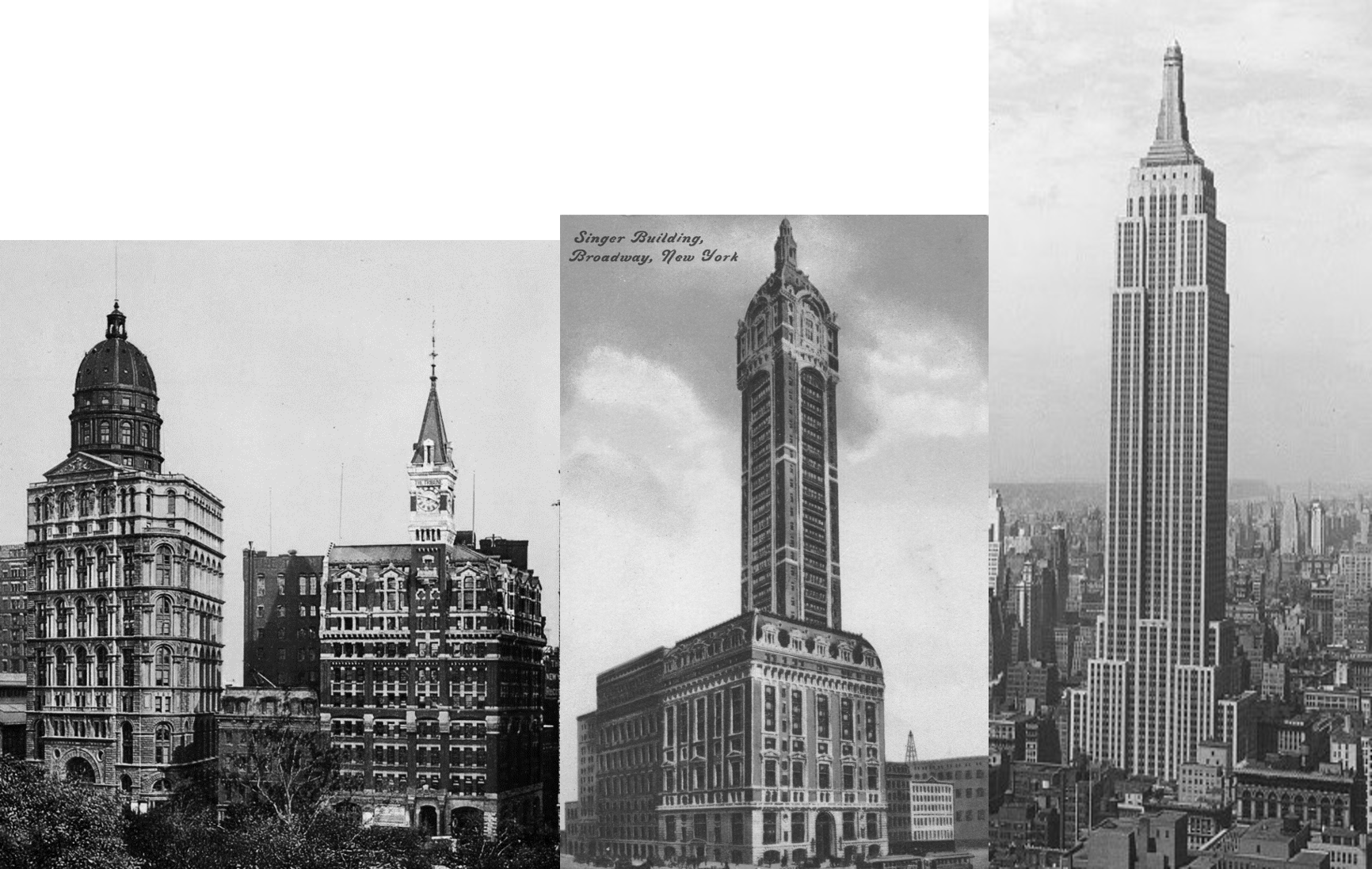

When the building technology to go tall was perfected, developers—be they corporations or individuals—realized they could add extra heights to convey information about the occupants or builders. The first record-breaking buildings in New York, such as the Tribune Building (1875) or World (Pulitzer) Building (1890) added decorative towers or domes to raise themselves above the fray and to express the power of their business or industry.

Early developers also added occupied towers. Both the Singer Building (1908) and Woolworth Building (1913) are large, bulky office building with extruded towers, which also play the role of Symbolic Height, though, in these cases, they also provided office space. It also shows that not all Symbolic Height is empty space or decorative spires.

And yes, developer and ego-based competition has driven buildings to be taller than they would otherwise be. The developers of the Empire State Building (1931) added a 61-meter (200-foot) dirigible mooring mast to lock in the world record, while Walter Chrysler added the 56-meter (185-foot) stainless steel spire—“the Vertex”—to beat out the Bank of Manhattan Building (1930) at 40 Wall Street. However, without this competition—this “Vanity Height”—the city would feel a little emptier.

There are examples around the world of practical uses for the voids up top. The Ping An Tower, in Shenzhen, contains a mass tuned damper that helps stabilize the building against wind forces. In the observation deck of the Shard, one can look up into the “Vanity Height,” hovering above; the experience helps enhance the pleasure when viewing the London skyline.

The Opposite is Also True

Not every record breaker or supertall has Symbolic Height. Both the Twin Towers (1972/3) in New York and the Willis (Sears) Tower (1974) have near-zero additional space above the top floor. Architectural modernism after World War II was a movement away from overt expressions of decorative height. The idea was that record breakers speak their intentions simply by being tall towers. Today, the view of “Billionaires Row” from Central Park shows wide architectural variety on top. 432 Park Avenue—like the former Twin Towers—just stops, with no decorative elements. A few blocks away, the rising Steinway Tower has a tapering, almost two-dimensional, 90-meter (295-foot) crown. Vanity or art? Perhaps both.

Symbolic Height: A Look at the Data

Despite some interesting examples here and there, we cannot say much about Symbolic Height, on average, because no one has analyzed more than a handful of buildings. To this end, using the CTBUH database of tall buildings, I have performed a statistical analysis to look at the patterns of Symbolic Height for about 2,000 skyscrapers worldwide.

The goal is to answer a set of related questions: Is Symbolic Height—the difference between the architectural height and the height of the highest occupied floor—a systematic part of the tall building universe? What has been happening to Symbolic Heights, on average, over time? Has it been rising, as is commonly assumed? Does the data support the idea of dissipative or wasteful competition among developers? And lastly, are China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) the worst offenders, as people commonly assumes? (Data sources and statistical results are here.)

Symbolic Height Around the World

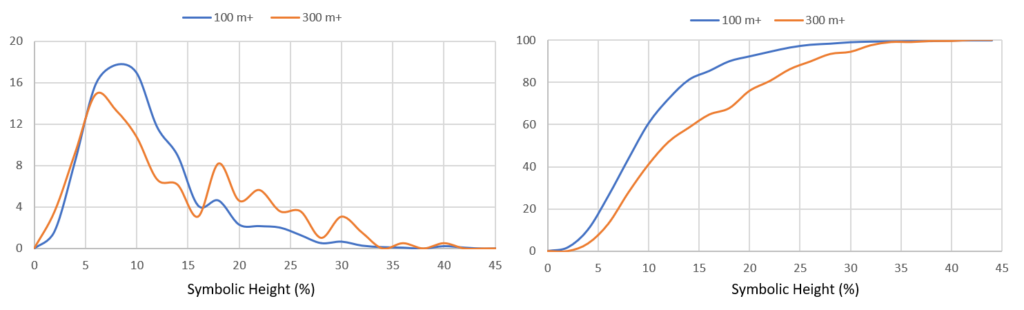

The answer to the first question is “no.” The average Symbolic Height, as a fraction or percent of total height, for buildings around the world of at least 100 meters is about 10% (with a median of 8%). In other words, on average, Symbolic Height represents only 10% of the total structure’s height, which suggests it typically plays a very small role. For supertall skyscrapers of 300 meters (984 feet) or taller, that average is still quite low at 12% (median of 9.7%).

This is not to imply that all tall buildings have a Symbolic Height of only 10%. There is a degree of variation—mostly on the low end. 75% of 100-meter or taller buildings in the database have a Symbolic Height of 12.5% or less. Only 5% have a Symbolic Height above 22%. For those at or above 300 meters, the numbers are similar: 75% of these buildings have a Symbolic Height of 18% or lower. Only 5% have 28% or higher.

Symbolic Height Over Time

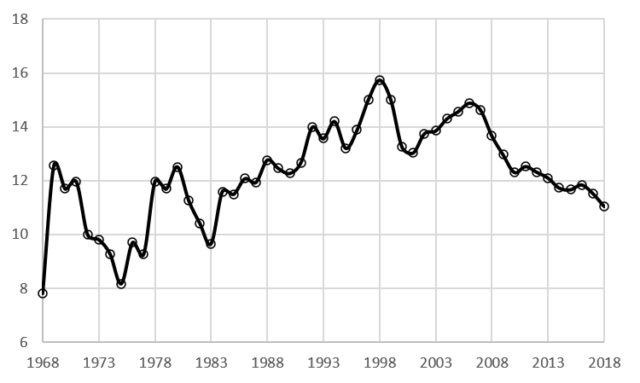

What about over time? Is Symbolic Height growing? Again, the answer is “no.” Using this data, I have created a Symbolic Height Index (analysis here), which gives the average Symbolic Height around the world each year, relative to the long run global average of 10%, after controlling for building location and use. The results suggest, first, that is no long run trend, but rather is cyclical. The Index peaked in the 1997 (a year when no new world record breakers were built), before Asian countries dove into the skyscraper game. As places like China and the UAE ratcheted up the tall building construction in the 2000s, the Index moved up until 2006 (before Global Financial Crisis) and has been falling ever since.

The Index also reveals relatively muted movements. Even in robust times, when more developers were adding extra height, the highest amount above the average was 7 percentage points. In other words, the data suggest that Symbolic Height is based on fashion or tastes, rather than developers need to systematically outdo each other. The findings also suggest that “irrational exuberance” is punished in the long run.

Symbolic Height by Country

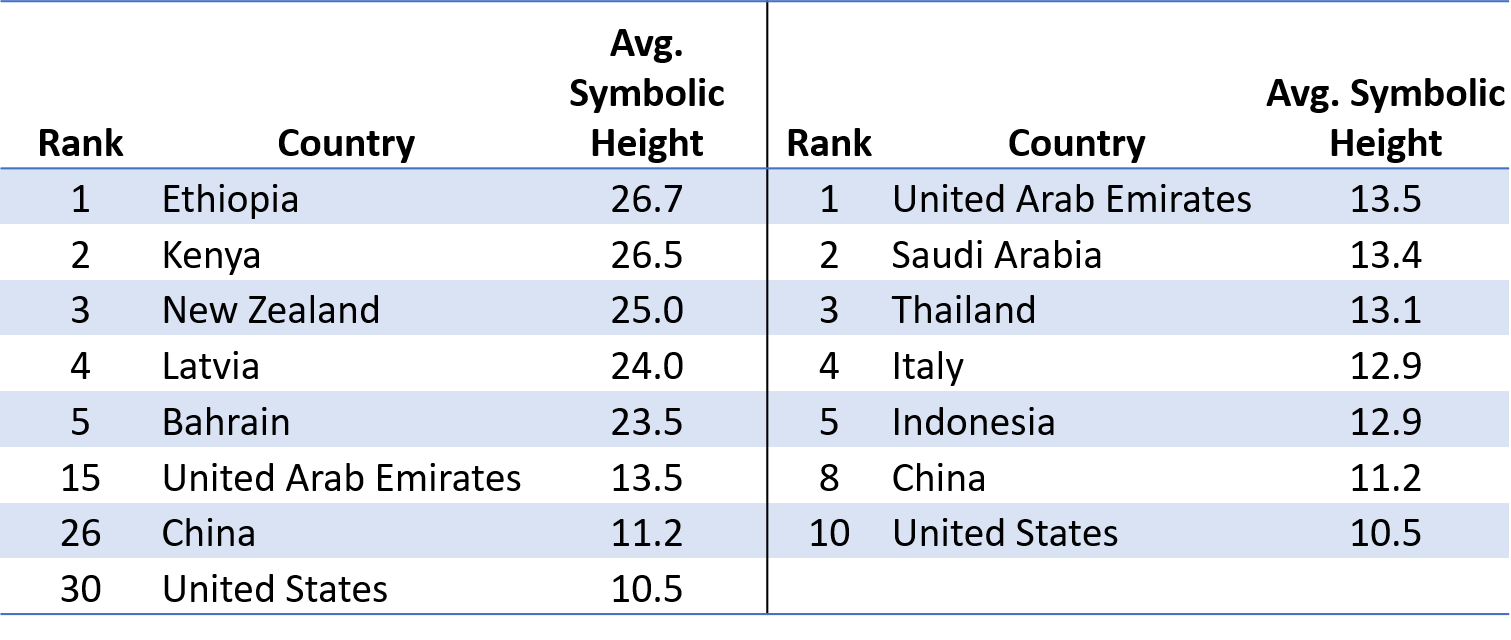

Which countries are the most egregious on average? The results of the statistical analysis are surprising. Among the 64 countries that have built at least one skyscraper since 1966, the top three are Ethiopia, Kenya, and New Zealand, with average Symbolic Heights of at least 25%. The UAE, China, and the United States are in the middle of the pack.

Just focusing on countries that have built at least ten skyscrapers, the UAE and China rise in the rankings. But their averages are still not that far above the global average of 10%. In short, when it comes to Symbolic Height, these countries about average. Among the public perception, China and the UAE appear to be “bad” because there are a handful of notable extreme cases. However, by focusing on those, we lose the skyline for the skyscrapers.

Variety is the Spice of Life

Given there is a certain cache to having a nominally taller building, the “stick-a-pole-on-it-and-declare-victory” type skyscraper is not likely to go away anytime soon. But a review of the broader evidence suggests that these types of buildings are the exception rather than the norm. There’s also little evidence that developers are engaged in a dissipative battle royale to beat each other for the title. So what if there are a few too-tall buildings out there? The variety alone makes it worth the cost.

Thanks to Maria Thompson for editorial assistance.

—

[1] Note that in my book, Building the Skyline (2016), and a previous blog post, I defined Symbolic Height in a slightly different manner. There, Symbolic Height was the difference between the actual or architectural height and the profit maximizing or economic height based on revenues and construction costs. Thus, Symbolic Height can include extra floors above the profit amazing height in addition to decorative elements or spires. Given that the two definitions of Symbolic Height are likely to be fairly close, on average, it can be a reasonable substitution for the definition of Vanity Height.

[…] excellence while also acting as symbols of economic prosperity and urban advancement. However, the symbolism associated with skyscrapers remains a topic of spirited debate. Some argue that these “towers of power” reinforce […]