Jason M. Barr September 16, 2020

Hong Kong on the Hudson?

When we think of New York City, we think of Manhattan and its supertall skyscrapers. As a result, we believe that New York is one of the densest places on Earth: a Hong Kong on the Hudson. And yet, craning our necks upwards diverts our attention from another fact. New York is not very dense at all when you look towards the horizon. Once you get out of Manhattan and past the historical outer-borough neighborhoods, you will find a distinctly suburban city. The landscape comprises block after block of one- and two-family homes, strip malls, and wide, car-friendly streets. New York is thus a tale of two cities—the skyline and the sprawl-line.

An Urban Greenhouse?

The “competition” between density and sprawl leads us to the question of which is worse for the environment, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, in particular. Skyscrapers are frequently criticized as emitting too much CO2—their size and heights make them particularly carbon-intensive. Because their facades contain broad surface areas of glass, they absorb a tremendous amount of sunlight, which means higher cooling needs, and more greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, running elevators, with heavy steel cables, is energy-intensive; the taller the building, the more CO2 production from vertical transportation.[1]

But when one discusses the carbon footprint of tall buildings, it’s vital to distinguish between the building itself and the occupants. Even the most efficient structure may be carbon-heavy if those inside use excessive amounts of energy. All else equal, wealthier households will consume more than lower-income ones, generating more carbon from their lifestyles. It is necessary to try to hold all things equal, if possible, to understand the impact of building heights per se.

Plastics, Benjamin

But, of course, free-standing houses in the suburbs have their problems. Since they are relatively large, they tend to have fewer people per square foot, requiring more electricity and fuel per person. Additionally, people who live out in the city’s less dense place are more dependent on their automobiles. Crave a pint of Ben and Jerry’s Cherry Garcia at 11:00 pm? You have to jump in your vehicle to get to the local supermarket. Need to get to work? It’s more convenient to drive since public transportation is thinner or less efficient out in ‘burbs. In this way, suburban homes are inherently linked to automobile transportation. You can have suburbs without cars, and perhaps you can have cars without suburbs.

The Efficient City

When discussing the trade-off between height and sprawl, however, we first must begin with a discussion of what urban form “should” look like if a city is going to efficiently allocate its valuable land to different uses. While much of city planning is about trying to arrange the city into neatly compartmentalized zones, economists have shown that cities are pretty good—though not perfect—at self-organizing themselves so that land is used in the best manner as possible.

The economics of urban form begins with the idea that land, as private property, is bought and sold in the marketplace. The question is, who pays for it, and at what price? To make things simple, let’s “anchor” the city with a central business district. Here land values are the highest. The reason is that businesses need to cluster together to perform better. Finance firms must be down on Wall Street. Marketing firms need to be on Madison Avenue, and so on. And they pay for the right to be there.

In general, the fundamental location decision for professional service-oriented businesses, who earn the lion’s share of the city’s income, is whether to remain in the cluster or not. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, midtown office rents averaged around $80 per square foot ($861 per m2). A firm could leave the center and save a lot of money. Office rents in downtown Newark, New Jersey, or Stamford, Connecticut, by comparison, are about half of that. But at what price? At the cost of losing an international reputation, access to the high paying clients, and a more skilled labor pool.[2] In short, firms in the center pay to play.

The Commute

These business districts draw workers who commute from their homes. For the most part, employees cannot pay more in rent than their employers, so most folks reside outside the business districts. But far away is the vital question. Here the decision, again, involves a trade-off. The longer the commute, on average, the cheaper the housing, since its less convenient. If you want a three-bedroom, two-bath house with a backyard, you need to expect to be traveling up to an hour to work each way.

That’s the fundamental trade-off that generate the city’s basic “spatial structure,” where people typically live and work (with the recognition that we are abstracting here for simplicity). High prices in the center generate high land values that naturally produce taller buildings, which at their heart, are an efficient use of land. Similarly, larger houses in the suburbs represent the perks of living further away—people get more space, both inside and out. Thus, even suburban living is usually an outcome that reflects households’ preferences and can be an efficient land use.

The Externalities

But, of course, the story does not end there. In the central city, tall buildings can generate negative “externalities”—unintended side-effects. The most cited ones are crowded streets, shadows, fears of gentrification, and the emission of greenhouse gases. On the other hand, sprawl also has negative impacts, including traffic congestion, racial and ethnic segregation, and greenhouse gas emissions from larger houses and extra driving.

The problem of externalities that one person’s decisions about where and how to live frequently do not consider the impact on others. When was the last time, for example, that you decided not to drive your vehicle because you feared that you would slow down other drivers when you got on the highway? If you and others thought that way, there would probably be no rush hour traffic! Or have you ever decided not to use your car one day simply because you knew that gasoline combustion produces a slight amount of odorless, colorless carbon dioxide that would enter the great flow of air that covers our planet? Not likely.

The point is that sometimes in life, you make a decision that impacts other people in a nearly imperceptible way. However, when thousands of people are doing this, the outcome is strongly felt—in this case, through rising temperatures and more erratic and dangerous weather patterns from CO2 emissions. So which kind of living—in the skyline or along the sprawl-line—is worse for climate change?

Carbon Production in New York City’s Housing Market

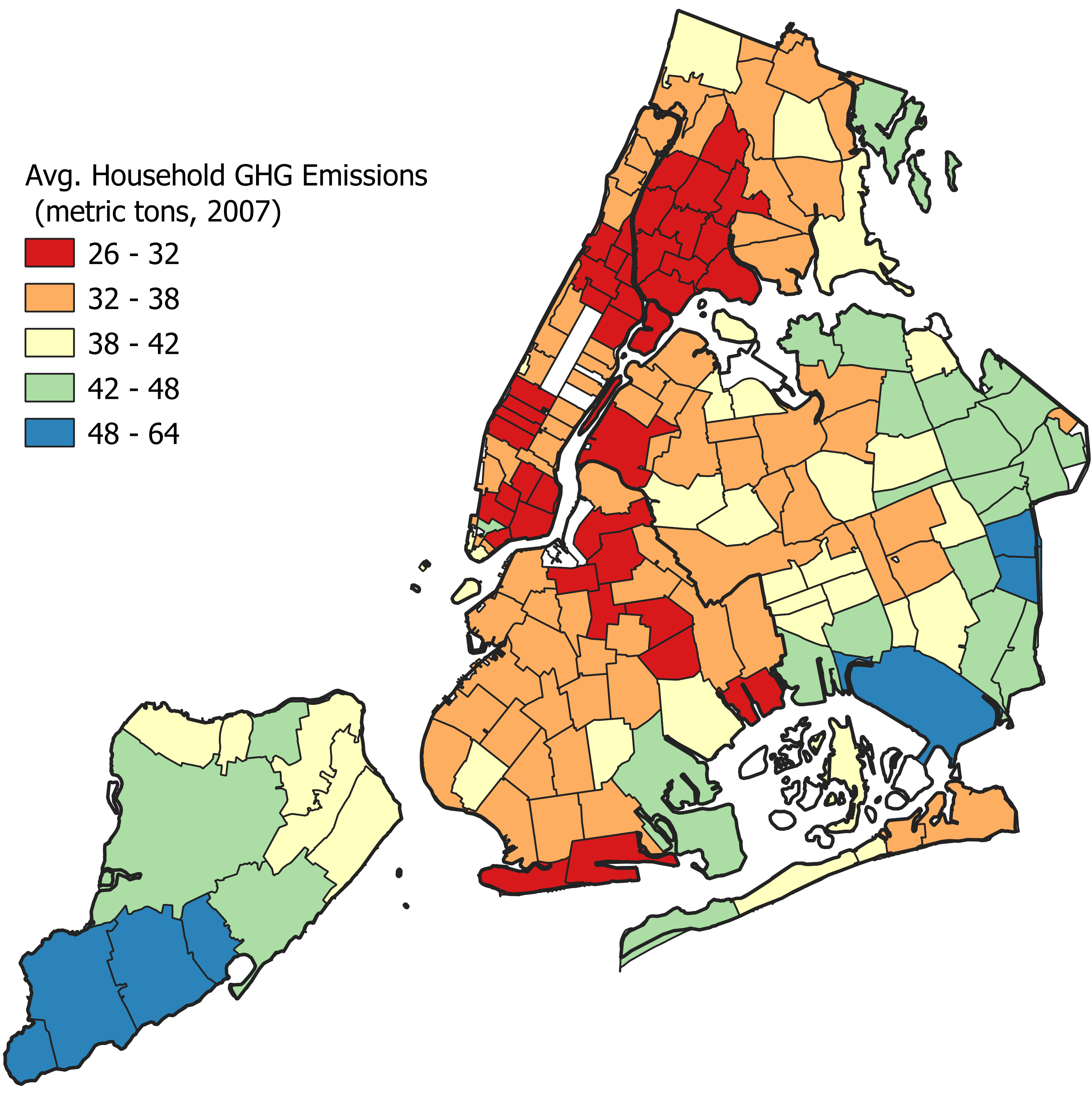

To answer this question, we need to investigate how residential building types affects greenhouse gas production, controlling for, or holding constant, other factors that might get in the way. To this end, I combined two data sets to analyze this question for New York City (the details and analysis can be found here). One part has the estimated average household CO2 production for each zip code. The other part comes for the NYC Department of City Planning and contains information about building heights and floor areas.

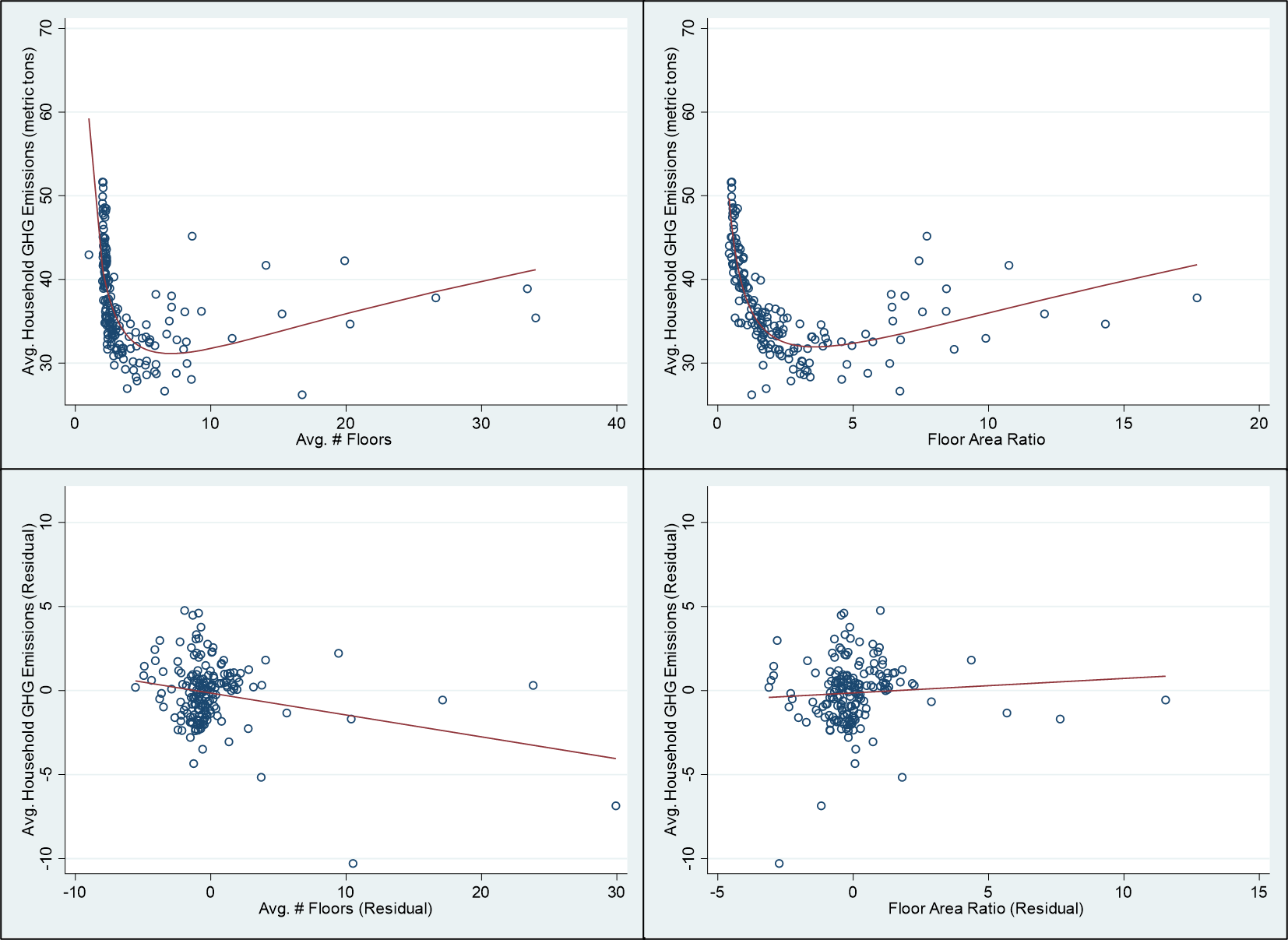

To see the impact of building form on GHG emissions, I performed a statistical (regression) analysis that looks at how average zip code building heights and floor area amounts impact GHG emissions, holding, other factors constant. First, the results show that, on average, without controlling for household income or driving behavior, there is a u-shaped relationship between heights or building areas and GHG production. The worst emitters live in free-standing houses in the suburbs and supertall buildings in the center—though the suburbs are worse in this regard (see the figure below).

However, after one removes the impacts of CO2 emissions from income and driving behavior, the relationship between building form and GHG emissions diminish greatly. General consumption patterns are are more important than if the unit is in the clouds or on the ground. In other words, the key to knowing whether a structure is GHG-efficient or not is to focus on two things: the average housing square foot per person in a neighborhood and its location relative the central city. Manhattan is much more energy-efficient than the other boroughs because people do so much less driving and live in smaller units.

The Right Policies

The lessons from this analysis are that, regarding household carbon production, building shapes matter less than income, driving frequency, and the amount of space that households occupy. As I have discussed before, the right policies need to be tied directly to consumer behavior and reducing dependence on automobiles (or getting rid of fossil fuels to power engines). Nonetheless, there are many in the planning community who advocate for “Goldilocks Density.” The perfect density—like New York’s Greenwich Village—they argue, should be imposed by fiat across the city. These areas have dense populations, but many lower-rise apartment buildings. The results of the analysis here, however, suggest that the theory of Goldilocks Density is misguided. Proponents look at the u-shaped CO2-building density curve and conclude that all places should have a residential floor area ratio (FAR) of three. But this like using a hammer to solve all carpentry problems.

The urban spatial structure that naturally emerges from countless individuals’ decisions reflects their choices in the faces of various trade-offs. Yet sometimes these decisions generate externalities. The solution is to make producing the externalities more expensive so as to reduce them without fundamentally altering the freedom of individuals or households to make choices about what works best for them. While the suburbs may be stultifying to some, to others, it is paradise. At the same time, people who drive and consume big houses need to pay for the harm they impose onto Planet Earth. Similarly, living on the 50th floor of a skyscraper may offer incredible views, but the carbon generated must be paid for. In the end, maybe some new towers will not be as tall, and some new suburban houses will not be as palatial, but they will remain if they provide people with a more rewarding life.

Read other blog posts on cities and climate change here.

I am grateful for valuable research assistance form Shaojie Wang and Ujjaini Desirazu.

[1] Another issue not addressed in this blog is that carbon emissions from the construction sector and the production of CO2 in manufacturing materials like concrete or steel. Skyscraper construction might produce more carbon on a square foot or square meter basic because it uses more materials and requires more machinery. As discussed in the conclusion, policies should be designed to tax carbon-heavy manufacturing and incentivize those processes and materials that generate less CO2.

[2] This is not to say that some jobs can’t be outsourced or done from m home, but the vital, knowledge-based jobs, and the spontaneous productivity that emerges from being at the same place at the same time cannot be outsourced.

[…] publicado originalmente em Building the Skyline em 16 de setembro de 2020. Traduzido por Marcella Cutrim Fernandes de […]