Jason M. Barr January 15, 2018

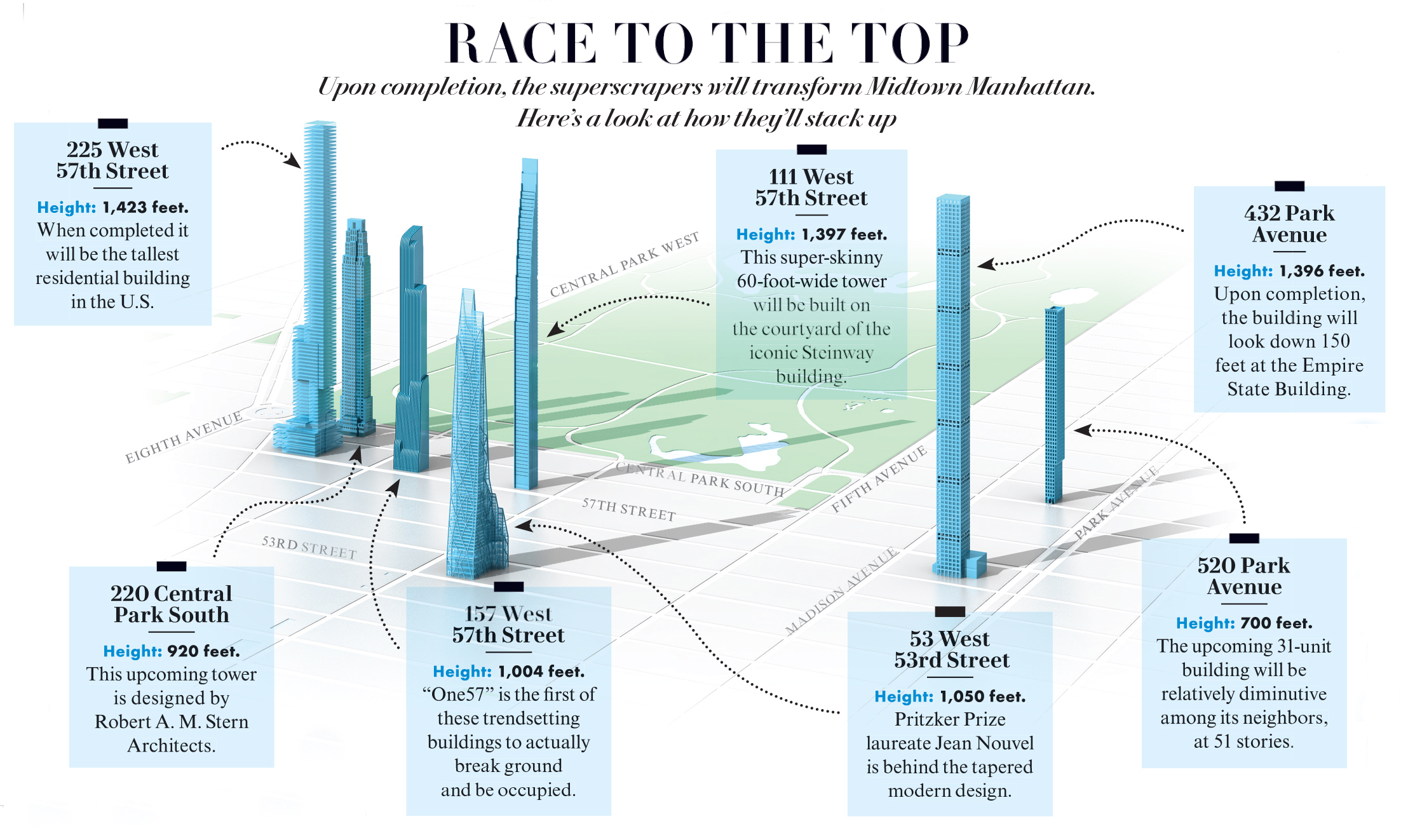

In the last decade, New York has seen the emergence of a new skyscraper type—supertall, superslim, ultra-luxury residential condominiums. As discussed in previous posts, the combined forces of new technology and economic demand have made them profitable projects. However, they have attracted their share of controversy, riling up feelings of anger and frustration in certain quarters.

Each of the many complaints, however, falls into one of three categories: (1) the buildings are the result of the machinations of corrupt plutocrats; (2) they erode the quality of city life; and (3) they damage housing affordability. Let’s discuss each in turn; and then focus on what’s to be done.

The Machinations of the Plutocrats

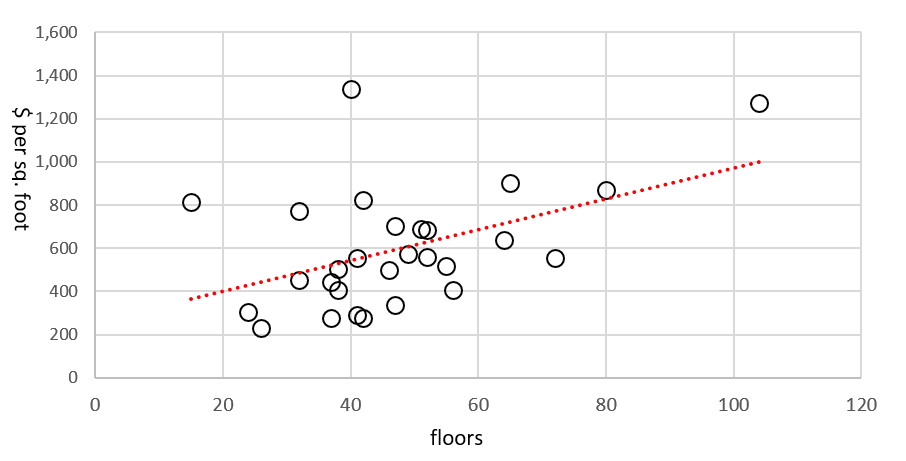

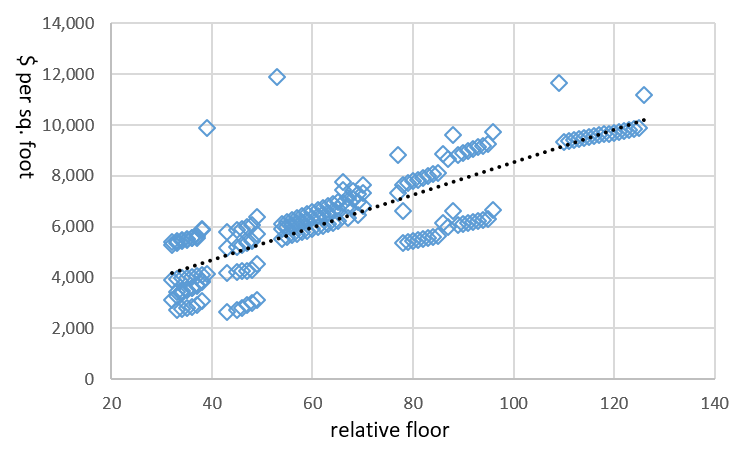

These supertall residential buildings represent nothing if not catering to the needs and wants of the ultra-rich. Condo prices generally range from $4,000 to $8,000 per square foot, while apartment prices across Manhattan average about $1800 per square foot. Headlines abound about those who pay one hundred million dollars or more for their units.

Investigations by the New York Times revealed that many apartments remain empty throughout the year, as they are purchased by foreign buyers who are just as interested in having a pied-à-terre as they are in hiding their ill-gotten gains. Many buyers use shell corporations to camouflage their identities, as luxury real estate is part of the money laundering chain.

Given the high returns on constructing these buildings, New York developers, it is argued, curry favor with city officials to build them, either by making campaign contributions or by promising to provide some token amenity, like a plaza or subway renovation, in exchange for the extra density.

The idea is that these skyscrapers represent a means by where corrupt rich buyers incentivize developers to further engage in corrupt real estate development so that the wealthy can protect their stolen gains.

Quality of Life

Another set of criticisms focuses on how they effect the urban fabric. Since many of the units remain empty most of the year, the vibrancy of street life that makes Manhattan so dynamic and compelling is, seemingly, being eroded. Empty buildings mean empty streets.

Relatedly, by replacing charming low-rise buildings that more organically mesh with the street line with cold towers set back in plazas, these structures erode the soothing feel of the city street. Lower rise buildings, it is argued, promote a kind of cozy urbanism—a scale that is more natural to the human soul. Large towers suck up this warmth by being too intimidating and creating dead space.

Another group of critics, especially those in the architectural community, feels they are just plain ugly. Finally, there are those who complain that they are thrusting shadows on Central Park.

Affordable Housing

The third set of criticisms has to do with housing affordability. First, constructing so many very expensive buildings, the argument goes, puts upward pressure on the prices of more modest buildings, reducing affordability in these neighborhoods. This can be called the contagion theory of housing prices; the supertalls are the “viruses,” which then “infect” the rest of the market with higher prices, exacerbating gentrification.

The second argument is that older, lower-quality buildings are torn down, thus displacing the local residents, who are forced to seek higher cost housing elsewhere. More broadly, by pouring money into the luxury market, developers then ignore construction in lower income sectors, which are badly in need of investment.

What’s to be Done?

In my opinion, much of the controversy surrounding their construction is a red herring. These buildings have become symbols of many current problems; but they are just that—symbols—projections of a collective frustration with housing affordability and income inequality, which are the real problems. Focusing on the superslims provides a convenient scapegoat, but the structures themselves are symptoms not the causes.

On Corruption

The biggest problem is that these apartments can be used as “safety deposit boxes” to hide illegal wealth. New York and the United States should not be in the business of “subsidizing” international corruption. Fortunately, steps are being taken that, hopefully, will mitigate the problem. In early 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department announced it would require title insurance companies to identify the names of those behind shell companies who buy high-end residential real estate with cash in six major metropolitan areas (including New York).

During 2016, the Treasury found that about 30% of the transactions covered by the program involved a buyer that was also the subject of a previous suspicious activity report. Whether this spotlight on the dark money is enough remains to be seen. The rich are certainly wily about finding ways to hide their money, and Donald Trump seems determined to give Planet Earth on a silver platter to his fellow billionaires.

On City Life

As for the supertalls ruining street life, I agree with Carol Willis, Director of the Skyscraper Museum, that there is little evidence of this in the neighborhoods where they are being built. Central Park South and 5th Avenue near the Plaza Hotel bustle with locals and tourists alike.

On the other hand, if you walk east a few blocks and stroll up Park Avenue north of 59th Street, there is no street life at all. Block after block are early 20th century luxury apartment buildings and very few pedestrians, save dog walkers and doormen. Yet no one complains that Park Avenue is soulless.

The “soulless streets” claim seems to emerge from the fact that people prefer the old to the new. I don’t disagree, but architectural preference cannot be used to dictate what gets built and what does not. Today the Gilded Age and Roaring Twenties apartments for the ultra-wealthy, such as the Dakota, the Beresford, and the San Remo, are charming and venerable. The superslims are labeled cold and distant.

Yet those venerable, old buildings were no less symbols of income inequality at the turn of the 20th Century as 432 Park Avenue is today. But Manhattan is not Manhattan without them. In a century hence, when 200-story buildings are going up, people will look at One57 and 432 Park Avenue with wistful nostalgia.

Shadows

As for the shadows problem, I agree that fewer shadows are better than more shadows, but all societies must balance various trade-offs. Limiting building height, will reduce shadows, but introduce other unintended consequences, including making super expensive buildings flatter and wider and gobbling up more of the older buildings on a street.

The 1961 zoning codes were specifically designed to help mitigate the shadows “externality” by limiting floor area and by allowing the sale of air rights. These rules force buildings to be narrower as they get taller, and they limit the total amount of floor area on a block. Unfortunately, some shadows in Central Park South is necessary. It is part of urban life. Having said this, a tax on empty billionaire apartments is a reasonable way to penalize people for hogging the sunlight when they are hardly ever in the city.

On Affordability

Do these houses contribute to an affordability problem? Only indirectly, but they are not the key culprits. The real problem, as, I have argued elsewhere, is that nearly 60% percent of housing in New York City is legally required to be one or two family homes. In other words, in many parts of the city, it is illegal to teardown a one-family house and replace it with, say, a five or ten-story apartment building.

The restriction of housing supply across the city puts tremendous pressures on housing prices. As long as the demand to live or invest in New York City exceeds the ability of the real estate community to supply housing, across the entire income spectrum, prices at all levels will increase. Only the rich can afford to pay those prices, while the middle and lower classes suffer disproportionately.

Gentrification is the result of upper income households using their higher income to box out lower income households in a city with a limited housing stock. It is easy for those evicted to blame their greedy landlords; it’s difficult to comprehend that tenants and landlords are tiny players in a market with nearly nine million people, and where everyday thousands of anonymous market transactions are taking place. All of us, seller and buyer alike, are embedded in this market system. Shouting at landlords and developers will not change the system.

A New Plan

The current zoning restrictions create a game of musical chairs, where the rich get “preferred access” to the chairs. The solution is that the city needs more “chairs.” Focusing on the superslims diverts attention away from that issue. The super-rich are not going to buy luxury condos in Elmhurst, Queens or Staten Island. How about more housing there, where it is needed? For this, we need a better, more enlightened housing policy from the city.

The claim that the new expensive condos create a price “contagion” is also a misleading diagnosis. Market prices move according to the laws of supply and demand. The superslims provide information about the demand by the wealthy and, as a result, condo prices are adjusted based on this demand. Sellers can raise prices all they want, but if there are no buyers, it is irrelevant.

Sadly, today, good economics make lousy politics. Change always has winners and losers, but without campaign finance reform, policymakers will have little incentive to think about the greater interests of the city, over doing what it takes to raise campaign cash. Vested interests and NIMBYism run deep in New York and it’s very hard to think large scale. The city desperately needs a new urban plan to reduce housing costs, improve transportation, and prepare for the effects of climate change. These kinds of plans can help erode inequality.

Why We Should Celebrate the Superslims

Rather than focusing on the towers as symbols of economic woes, we may want to consider their positive aspects. Manhattan is a global city, in part, because of the wonder of its skyline. Adding towers to midtown and downtown serve to enhance that skyline and allows the city to continue to grow and retain its iconic reputation.

The superslim towers represent novel creations, and decades from now we may look back and appreciate them in the way we appreciate the Chrysler or Empire State Buildings (though we may find this hard to believe today).

New York’s growth and success is due to its creativity and problem solving. So let us not blame these skyscrapers for the high cost of housing or rising income inequality, but rather let us begin by tackling the real underlying economic and political problems of the city.