Jason M. Barr May 31, 2018

A growing body of research demonstrates that across the United States there is significant variation in household greenhouse gas emissions.[1] Regionally speaking, the “sweet spots” are those places with warm winters and cool summers, such as California.

Within regions, however, CO2 emissions have an inverted u-shape. Starting in the rural areas, household carbon production tends to be low or moderate. Moving toward suburban areas, emissions rise and then peak. They then fall in the densest central parts of the city.

The reason is due first to income. Wealthier neighborhoods in the suburbs have larger houses, which need to be heated in the winter and cooled in the summer. Second is related to driving patterns. People who live in the suburbs spend more time commuting, and using their cars for shopping and other daily activities.

Inside central cities, a few things are at work to lower a neighborhood’s greenhouse gas emissions. First is that people are more likely to live in smaller units—in apartment buildings or multifamily houses. This means simply that they consume less space, which generates, on average, fewer greenhouse gases. Just as importantly, people in dense urban areas are more likely to walk or take public transportation, both of which produce less CO2 per person.

Leaving Grand Central Station

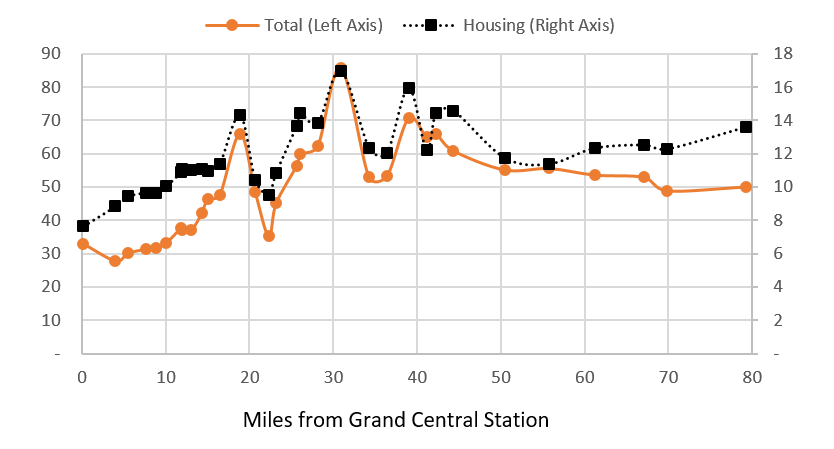

Imagine now that you are in Grand Central Station in the heart of midtown Manhattan about to board a train going north on the Harlem Line. If you measured the average household CO2 emissions in the neighborhood or town around each train stop, you would notice the inverted u-shape (shown in Figure 1).

In the heart of Manhattan and the Bronx, greenhouse gas production per person is low, but steadily rises as you travel outward into the suburbs, peaking in the wealthy suburb of Chappaqua (there’s a dip in White Plains, a small city 20 miles north of midtown). After that, the towns are more rural in character and less likely to be in the zone of influence of New York City. In short, urban density is good for lowering emissions (and households in the suburbs should pay for their harm).

Building Shape and GHG Emissions

Returning to the big city, however, where there are lots of skyscrapers, an important questions remains: How do tall buildings influence greenhouse gas emissions? We can imagine that the size of a building matters—more space means more emissions. But what about height?

Let’s say we have two 100,000 square foot buildings. But one is 10 stories, with floor plates of 10,000 square feet, while the other is 20 stories, with 5,000 square foot floors. Does the taller one have different emissions than the shorter one? To investigate this question, we turn to data provided by New York City.

Local Law 84

New York’s Local Law 84 was passed in 2010 with the goal of benchmarking water and energy usage, as well as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The law mandates that specific structures—mostly large apartment buildings and commercial properties—participate.

In total, about 2.3 billion square feet of private sector real estate and over 281 million square feet of public sector real estate is tracked (nearly half of the city’s 5.5 billion square feet of building space). However, one and two family houses are omitted. Of the nearly 830,000 structures in New York City, about 70% are comprised of one or two family homes (though they contain less than half of the total floor area).

The law requires only the reporting of usage and emissions, but does not dictate that owners reduce CO2. The hope is that by forcing landlords to be informed, they may voluntarily take action, or that the information will put competitive pressure on owners if tenants demand reductions. The efforts appear to be working, as the evidence supports lower emissions over the last three years, though it is not clear why. It could simply be due to weather patterns or a recent law that forbids the use of the dirtiest kind of heating oil.

CO2 Emissions: Some Facts

New York City posts the building data. To this end, I downloaded it and combined it with other data published by the city. While the data set contains information on many types of buildings across the city, here we will focus only on residential buildings, specifically the category of “multifamily housing.” (Information about the data set and the statistical analyses can be found here.)

Let’s begin with some statistics. According to Jones and Kammen (2013), the average person in the U.S. produces about 20 metric tons of CO2 per year (about 48 metric tons per household). Also the average person in generates 5.6 metric tons of CO2 per year just from housing. (A typical garbage truck weighs 23 metric tons.)

Using the New York City data, the average apartment building produces 5.4 metric tons of GHGs per 1,000 square feet of building space. On average, each person in New York City occupies about 405 square feet of housing. This means that the average housing of GHG emissions per person is 2.18; about 61% less than the average across the U.S. It certainly suggests that multifamily housing produces lower emissions.

Emissions versus Height and Area

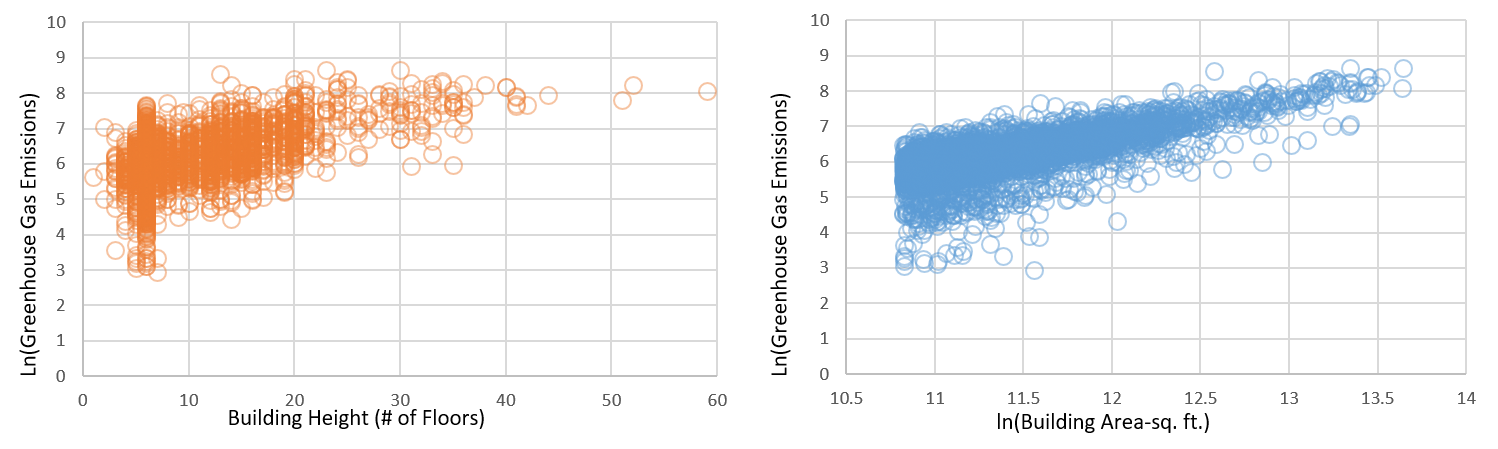

Using the New York City data, we cannot, however, compare single family houses to apartment buildings, but we can look at apartment buildings of various heights and sizes. Ultimately, the question we would like to answer is, how does housing form affect the per capita production of CO2? To begin, Figure 2 shows the relationship between total GHG production and building height (left), and building area (right), respectively for multifamily residences.

As one might expect, building height and area are both positively associated with CO2 emissions. But it is also likely that taller or larger buildings are occupied by people with higher incomes, who would naturally generate more CO2. Thus one of the key measurement problems is separating out the building form itself from the behavior of the occupants.

A notable example is that of the Bank America Tower in New York in midtown. Opened in 2010, the 55-story skyscraper was praised for being one of the greenest in the city, earning a Platinum LEED Certification. But in 2013, thanks to Local Law 84, it was discovered that the building was actually one of the highest emitters of carbon dioxide in the city. The reason was the tenants—bankers tend to use energy intensive computers.

For us, however, the concern is with the structure itself. In order to estimate the impact of building form on GHG emissions, a statistical (regression) analysis was performed that investigates how building height and square footage impact total emissions, controlling for a host of other things that might affect carbon production.

To account for the effect of income and demographic characteristics, I measure the impact of the census tract on emissions. That is to say, buildings in high income census tracts are likely to have high emissions. Thus, my procedure implicitly controls for income and the GHGs that might come from richer tenants.

The Findings

The statistical analysis demonstrates a few key findings. First is that building area generates a “returns to scale” with respect to greenhouse gas emissions. A 10% increase in building area, generates about 7.1% increase in emissions. This means that, on a per person basis, larger buildings reduce the average carbon footprint of each occupant.

Take two apartment buildings identical in every way, except one is 100,000 square feet and the other is 110,000 square feet. Say the first building emits a total of 500 metric tons of GHGs per year. We would estimate that the second would generate 536 tons (an 7.1% increase). Assuming that each person occupies 400 square feet, then each of the 250 residents in the first building is emitting 2.17 metric tons of GHGs; while the second building has 275 residents, giving a per person emissions of 1.95, a 10% reduction.

The Height Effect

In regard to building height, holding the building area constant, an increase in one floor is associated with 1.9% increase in GHG emissions, on average. But, in truth, the effect of building height is a little more complicated in two important ways. First, is that while 1.9% is the average effect, there also seems to be a leveling off of emissions growth. That is to say, as buildings get taller the increases in emissions are lower. Going from say 10 to 11 floors has a greater increase that going from 20 to 21 floors, on average.

Second, a comparison of two buildings with the same building area, but different floor counts is only possible if we are looking at “marginal” differences. We cannot logically say that one building that is 20 stories taller than another, with the same floor area, has nearly 40% more emissions because, with reasonably sized buildings, going taller and taller means building skinnier and skinnier; one runs into limits about how small a building footprint can be. Typically, in New York City, building tall is only feasible if a developer amasses a large enough lot.

For this reason, it is important to investigate the interaction between height and size—that is, to account for the effect of building height, when one also increases the building area. After doing this analysis, I find that as buildings become taller (and larger) there is again a flattening effect—the increase in the size of the building reduces the impact of building height. (See here for estimates of the effect of building height for different size buildings).

So, on one hand, increasing building height increases per capita CO2 emissions, while on the other hand, increasing building size reduces per capita emissions; the per capita savings from doubling the size of the building offsets the doubling of the height (again, if we assume that all people consume 400 square feet of space, and that everyone has the same income and consumption patterns).

Remaining Questions

In summary, increasing building height does raise CO2 emissions, on average, but, because height and size are not independent in most cases, the net effect is not always clear. The statistical analysis here suggests that the size effect reductions can dominate the height effect increases.

But the results raise a few important questions. First, what is driving the height effect? One possibility has to do with the additional plant and equipment in taller buildings, including elevators. Another is the cost of heating and cooling that might come from more exposed facades.

Secondly, what happens to net GHG emissions if we take a typical suburban home and “place” it on top of a central city highrise? That is, what happens to carbon dioxide production if a suburban family leaves its single family home and moves to a newly built floor in a highrise? Is there a net saving in household carbon production?

These questions are to be taken up in future posts.

Sameera Jhunjhunwala provided valuable research assistance.

———————–

[1] For the purposes of this blog post, I’m going to use the terms “greenhouse gas” and “CO2” interchangeably. Carbon dioxide is the primary greenhouse gas emitted through human activities. In 2016, CO2 accounted for about 81.6% of all human-caused U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.