Jason M. Barr June 18, 2018

Have you heard the old joke about gravity—it’s not just a good idea, it’s the law! Ignore the law—say by jumping off a cliff in an attempt to fly—and suffer the consequences. The same can be said about supply and demand in economics—supply is not just a good idea, it’s the law. Evidently, when it comes to housing affordability, cities and nations world over are trying to ignore it at their own peril.

Today, there is a giant disconnect between the sentiments of economists and the residents of cities. There is near universal agreement among those in the economics profession that the more building restrictions a city has, the greater are its housing prices. There is a vast amount of evidence to demonstrate this.

Yet residents who are worried about affordability don’t seem to quite get the nature of the problem: restrict supply and price will go up. Instead, people go searching for villains—greedy landlords, wealthy developers, or middle class gentrifiers. While such targets are in plain sight and easy to scold, blaming them misses the point: housing market restrictions creates a fixed pie with winners and losers—where “rare” housing is redistributed to those with higher incomes. At the risk of exaggeration, severe restrictions turn the housing market into a kind of auction, where the highest bidder wins and everyone else remains empty handed. It doesn’t have to be this way.

The Law of Supply

What exactly is the Law of Supply? Very simply, it says that if prices rise then, in the short and medium run, businesses will deliver more products to the marketplace. A higher price incentivizes producers to increase production because it generates more revenue. In the longer term, if prices remain high, this will induce more firms to enter the market. The additional output will then cause prices to fall or moderate.

Here, in the 21st century, living in a world dominated by the market provision of goods and services, the law of supply is taken for granted in nearly all aspects of our lives. When we go to the store we know that milk will be on the shelves. When we go shopping for a new car we don’t even bother to think that maybe no cars will available. The reason is simple, the dairy farmers and the car makers of the world can offer their products at reasonable prices, while making a profit.

We take Adam Smith’s dictate as a self-evident truth: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” The baker supplies bread because he can earn a profit. In nearly all aspects of our lives we let the market do its thing, and it utterly banal and uncontroversial.

But somewhere along the way, people seem to have forgotten that the Law of Supply also applies to housing. If you make it hard for the market to provide it (or prevent the government from doing so as well), guess what happens? Prices remain high. At its heart, it’s really that simple.

Housing Supply: The Evidence

In their nearly-comprehensive review of the academic literature on the effect of land use and building regulations on housing prices, economists Joseph Gyourko and Raven Molloy (2015) conclude, “The vast majority of studies have found that locations with more regulations have higher house prices and less construction.”

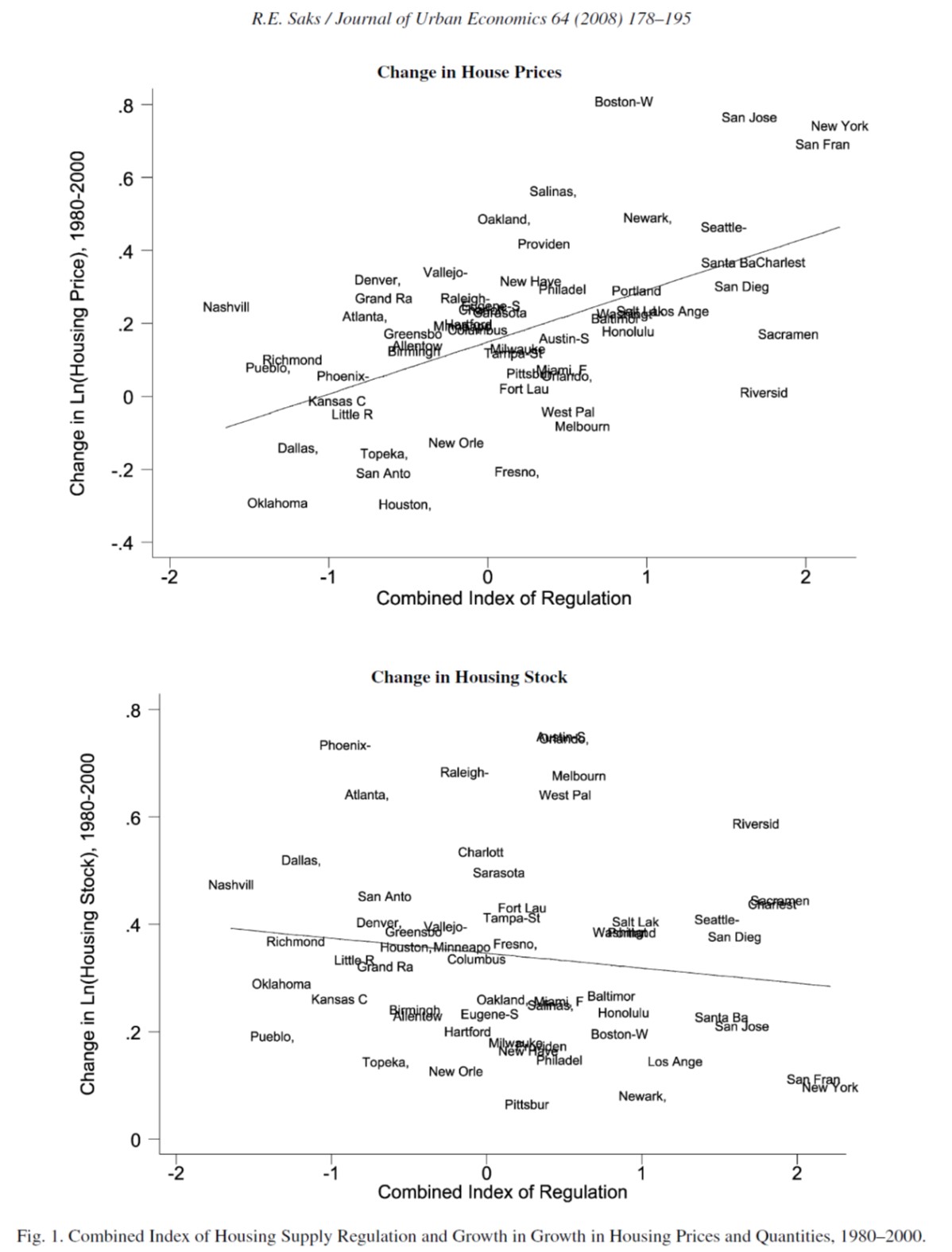

Research by Raven (Saks) Molloy (2008), for example, demonstrates this clearly. As Figure 1 shows there’s a positive relationship between the index of building regulation and the price of housing across urban areas in the United States. Her research also shows that higher housing prices act as a barrier that prevents economic growth. Places were housing is more expensive also have lower job growth.

Why the Denial about the Law of Supply?

Building regulations take many forms. They include the length of time and amount of paperwork needed to get a building permit; community power to veto new projects; and a suite of zoning rules, that can include restrictions on building heights, lot sizes, and the types of buildings at different locations. All these generate barriers to entry–they prevent builders from adding to the housing supply to match the demand.

The history of zoning shows that it has rational and reasonable origins. In the early 20th century, as the automobile made businesses much more mobile, homeowners asked their elected officials to embrace building restrictions as a way to protect them from factory pollution and other “incompatible” uses that might make a residential neighborhood unhealthy or unpleasant.

Along the way, it was discovered by homeowners that zoning had some unintended, beneficial side effects for them. By limiting construction and by requiring things like mandatory lot sizes and building height restrictions, it increased the value of their real estate investments. Furthermore, zoning was a legal means to keep out the poor and minorities from homogeneous neighborhoods. In the process of imposing all of these rules and regulations, restrictive zoning became the norm.

It has also made the Law of Supply a controversial issue. To suggest that a freer market do what it normally does when it comes to housing induces a fear of change–that adjusting to a world with more housing, taller buildings, and lower prices will negatively impact residents and their neighborhoods. Unlike milk or cars, property is fixed in space.

Living in a house also means living in a neighborhood—a complex ecology of real estate, infrastructure, institutions, and people (and raccoons, rats, squirrels, cats, and dogs, etc.). The general list of complaints is always about forces that can’t necessarily be controlled.

The Complaints

Such complaints include:

- New construction is going to ruin my home values.

- I like my neighborhood the way it is.

- Construction demolishes historical architectural gems.

- New housing will cause more traffic congestion, and place a burden on local services and schools.

- New housing is going to “tip” the neighborhood in the “wrong” direction.

- Taller buildings are bad for street life.

- New construction is loud and annoying.

There’s a 101 reasons why every resident is against new housing in their neighborhood, yet this is tantamount to saying the affordability problem is someone else’s problem. This is a kind of Prisoner’s Dilemma game: what’s rational for the individual in the short run (vetoing change) is bad for everyone in the long run (including the naysayers).

What Can be Done?

The collective benefits of increasing population density and housing are huge. First housing costs will drop, saving people money, and likely increasing employment opportunities, and lowering income inequality. Fewer cars will be on the road; less greenhouse gases will be emitted; and potentially people will be happier and healthy.

To be clear, the answer is not to eliminate zoning and building restrictions. The government needs to regulate housing and land use to best balance the needs and well-being of all residents of the city. But the way to do it is to create a new plan that reflects the realities and needs of the 21st century (including the looming devastation from climate change).

Politicians do not want to make large scales changes because residents and leaders think short term—only about the world they have now and not the world they could have. Leadership—a rare skill—requires not only a vision of what a better future could look like, but also the skills and capabilities to bring people along to effectuate that shared vision. Doing nothing or making token changes is the easiest thing to do and feels like the best route. This is the status quo bias. The present becomes a reference point for what is normal, and deviation from this point generates anxiety because it is seen as moving to worse state.

A large scale change must have three properties: it must be comprehensive, fair and reasonable, and have provisions to compensate those harmed by the changes. In short, it must designed not only to move a city to better world, but also to alleviate the fear of change.

Comprehensive

The first element needs to be a rezoning of the entire city that encourages more density and mixed-used neighborhoods, including low-rise apartment buildings in the suburbs and highrise housing in the central city. Rezoning a few neighborhoods for more highrises in already dense neighborhoods will not do the trick. The entire housing stock of the city must expand by a wide margin. For example, economist Jerry Nickelsburg estimates that across California, more than three million new houses and apartments would need to be constructed to make housing affordable.

Second, it needs to also include a transportation plan that considers cars, buses, subways, and bicycles (including autonomous vehicles, and ridesharing) all at once. Housing and transportation go hand in hand. And, if people are told that their neighborhood might change, but because of improved transportation they will have easier access to more urban amenities and employment opportunities, they’ll start to see the benefits.

Lastly, there needs to be a plan for non-transportation related infrastructure. For example, a plan needs an “automatic trigger” to produce new schools when the population hits a specific threshold. Again, if people know that public goods were going to automatically be provided, they would not only come on board but they would be able to benefit from the changes. These new infrastructure projects can be paid for by the growth created by a denser city.

Fair

In order for a plan to been seen as fair, it should be created with as much input from as many constituents as possible. That is not to say everyone is going to get what they want. But the point is that a city is a diverse and complex system. It’s this diversity that makes cities so fascinating. Any city must therefore recognize the value of this diversity by allowing for a heterogeneous city, with a diverse set of land uses and building types.

Part of the reason why people reject changes is because they see it as unfair—that their neighborhood is being singled out, while other neighborhoods are left alone. The key to fairness is comprehensiveness. A new plan should relate to the entire city at the same time, so no one can claim that other groups are getting special treatment.

Compensatory

As I have discussed in a previous post, one of the ways to get buy-in is to establish a series of programs that will make the transition easier. People can’t just see a new urban plan as all pain and no gain; this is what gives rise to NIMBYism. To ease the transition, policies can include home-value insurance, renters saving accounts, renters moving fees, and payments (or reduced property taxes) for infilling or densifying a residential property.

Toward a Better, Afforadable City

In 1975, when the New York City government was on the brink of declaring bankruptcy, then U.S. president Gerald Ford threatened to veto any federal bailout package (and which prompted the Daily News to print its famous headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” though Ford never said those words). By this time large cities like New York were considered outdated and hotbeds of crime, vice, and poverty. The Hollywood idea of turning Manhattan Island into a federal penitentiary was not all that farfetched.

Today, large metropolises like New York have rebounded and are more important than ever to the national and international economies. Ironically, smartphone and internet technology, and the new industries they have spawned, have made big cites hotbeds of innovation and job growth.

This has created a situation where the demand to live in these areas has outstripped the real estate community’s ability to accommodate this demand. As a result, housing prices keep rising. Building regulations and zoning have created a game of “fixed pie-ism,” where people with higher incomes can buy their piece of the pie and the rest go hungry. The key is to expand the pie.

Repeat after me: “Supply, it’s not just a good idea; it’s the law!”