Jason M. Barr August 6, 2019

Note: This two-part series is adapted from chapters seven and eight of my book, Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers (OUP, 2016), which is based on research (here and here) performed with Troy Tassier of Fordham University.

The Bedrock Myth

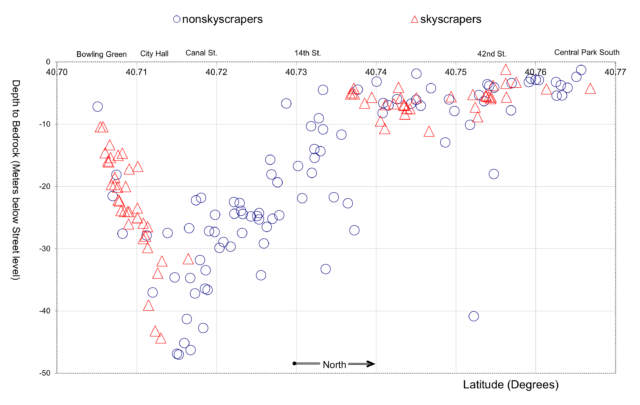

An aerial view of Manhattan reveals the shape of its curious skyline: a cluster of skyscrapers Downtown and another one in Midtown, but few in between. The conventional wisdom is that skyscraper developers gravitated to these areas because access to bedrock near the surface made it easier to create foundations.

As discussed in Part I of this series, this conventional wisdom is false—a confusion of correlation with causation. Lower Manhattan, in fact, had some of the worst geological conditions in the island. Because the bedrock there is below the waterline, it is covered with wet sand. This required expensive foundation technologies—most notably caissons—to anchor skyscrapers to the bedrock. Developers willingly payed these costs because the rewards were so great—high rents from the many corporations clustered Downtown.

In the region just north of City Hall, where the bedrock was deeper down, developers had no interest in constructing tall buildings because they contained dense tenement districts. Here, the residents had no ability to pay the high rents needed to justify the costs of high-rise construction. If there was a demand for skyscrapers there, builders could have used caissons to create the foundations.

Looking back at the history of the skyline in the 1960s, geologists saw no skyscrapers where bedrock was deepest and made the false conclusion that it was their depths that scared off developers. But the truth is just the opposite: places with the deepest bedrock also had the lowest demand for skyscrapers.

The Midtown Myth

But this begs the question, if geological conditions where not influential, then what caused the rise of Midtown as the nation’s largest skyscraper district? Another conventional wisdom permeates the discussion: the location of Grand Central Terminal. Forced by city officials to keep its terminal north of lower Manhattan, in 1871, the New York Central Railroad opened a depot at its current location on East 42nd Street.

The story holds that this area developed as a natural focal point because it created a giant transportation hub. However, the problem with this argument is that the tracks were exposed until 1913, when they were electrified and covered. Before then, the neighborhood north of the station was polluted by coal-infused steam from the locomotives. Out of the seven crosstown streets passing through the railroad’s property, north of 42nd Street, only two were open for vehicles; the rest were for pedestrians.

Midtown 1.0: Madison Square

A closer look at building patterns before 1913 reveals that the Grand Central Terminal neighborhood was not of interest to skyscraper (and office) developers during the earliest years. The first skyscraper north of Downtown was the Flatiron Building completed in 1902. It was built on a triangular plot between Broadway, 5th Avenue, and 23rd Street. The first world-record-breaking skyscraper north of City Hall was the Metropolitan Life Tower, completed in 1909, on the corner of Madison Avenue and 23rd Street, across from Madison Square Park.

Founded in 1868, the company originally opened an office there in 1893. MetLife introduced the strategy of having its agents go door-to-door, collecting monthly premiums. Presumably, by having their offices at Madison Square, agents were much closer to their customers. Its success at that location prompted it to construct its tower; this strongly suggests that Madison Square was the center of business and commerce north of lower Manhattan. The Chrysler and Empire State Buildings, further north, were completed a generation later.

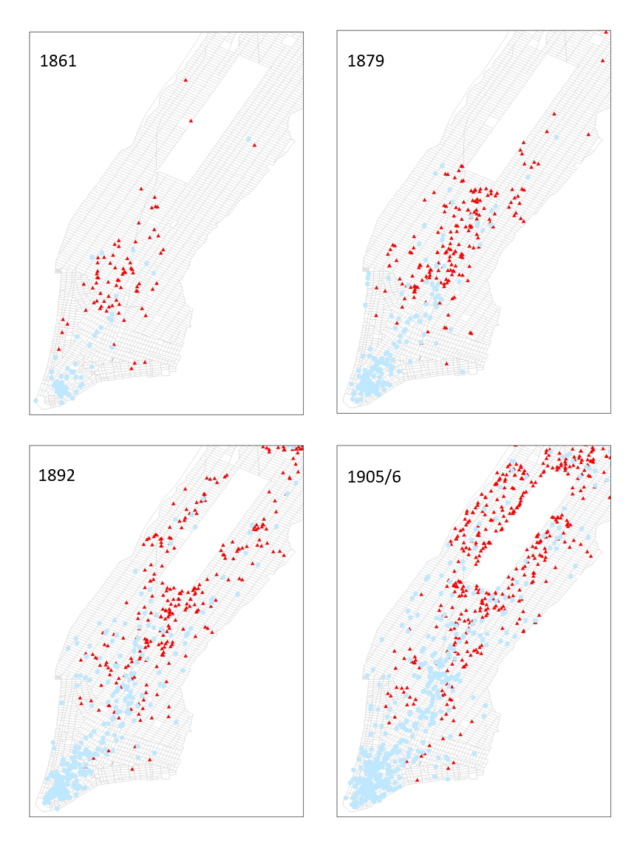

The “Jump”

The figure below shows the pattern of skyscraper construction during this generation. Each dot represents a building that is 80 meters (262 feet) or taller. The figure on the left shows that during the decade or so between 1890 and 1901, all the skyscrapers were constructed Downtown, the sole exception being the tower of Madison Square Garden. Then, suddenly, starting in 1902 there was a “jump” where skyscraper completions were evenly divided between Downtown and Midtown. The maps indicate that around the turn of the 20th century there was a tipping point, where developers saw opportunities north of 14th Street that did not exist in the decade prior, despite the fact that little had changed in the neighborhood around Grand Central Terminal, which would not be rebuilt and completed until 1913.

The graph also reveals that Midtown construction was split between two areas. The first was between Union and Madison Squares, from 14th Street to 26th Streets; the second area was along 42nd Street, running west from Grand Central to Times Square. But the greatest concentration was around Madison Square.

The corridor along 42nd Street was likely influenced by two changes occurring in the first two decades of the 20th century. First, as mentioned above, was Grand Central Terminal. Second was the completion of the first subway line, which began at City Hall, ran up to Grand Central Terminal, then cut across 42nd Street to Times Square, and from there up Broadway. The line may have influenced the early shape to some degree, since developers and businesses saw opportunities along the lines. But as I will argue below, these transportation developments, while playing a supporting role in the rise of Midtown, were not the cause of its emergence.

The Birth of Commuting

To understand the reason for Midtown’s birth, it’s necessary to go back in time—to the 1830s, actually. This was the period when the seeds of Midtown were being planted. Up until that time there was no such thing as mass transit. Most people got around on foot. Horse-pulled coaches were available, but they were relatively expensive and limited in capacity.

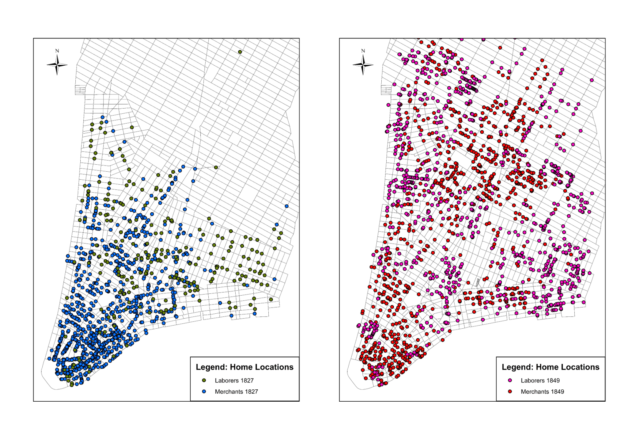

The pedestrian city, as a result, generated a particular urban landscape. The wealthy tended to live closer to the very tip of Manhattan, near the port and seat of government. Here they could easily walk between their homes and their employment. The poor, on the other hand, could not afford to live in the center; as a result, they tended to cluster along the outer fringes of the city, which was then the area just north of City Hall. Without mass transit, the city had the opposite layout as to what we normally see today. The rich lived in the center and the poor lived on the periphery.

But then in the 1830s, this began to change. First came the horse drawn omnibus in 1829—a large stagecoach outfitted for mass transit. Next, in 1832 came the horse drawn streetcar, which was driven on rails embedded in the road. The streetcar produced less friction and was thus able to move more people with fewer horses. In short, these transportation innovations created, for the first time in American history, the possibility for people to live further away from their homes and commute to work each day.

The First Inversion

New Yorkers embraced this opportunity. This resulted in what I call the First Inversion. In the 1830s, the wealthy began an exodus from their homes in lower Manhattan. But rather than simply shifting their residences a little to the north, outside the growing business district, they “jumped” over the working class neighborhoods, such as Five Points, and the Lower East Side into the less developed northern areas of the island, such as Washington Square and lower Fifth Avenue. The working classes remained in their historical enclaves because they could not, or would, not pay for mass transit. This transition created a new pattern. The business district was at the lower tip of the island. North of that were the crowded tenement neighborhoods. Above that were the middle- and upper-class residents, living in their townhouses.

Geology and Manhattan

As discussed in Part I, depths to bedrock did not play a role in the formation of Midtown. But this is not to say that geology, more broadly, was inconsequential. In fact, the geological roots of the city are strong, but not in the way most people think. Rather, the geological story of importance is the long history of plate tectonics, and the coming and going of glaciers during the various ice ages. These events created Manhattan Island—two miles wide and 13 miles long. The “tubular” shape of Manhattan, combined with the First Inversion, is what created Midtown 1.0.

Through the 19th century, as Manhattan’s population swelled, it reinforced the pattern after the Inversion. The immigrants pouring into the city went to the tenement neighborhoods, where housing was cheap and lower-skilled jobs most accessible. The middle and upper classes tended to move north on the island, and commute to work.

Manhattan’s Shape

Manhattan’s shape is different than most cities. Chicago, for example, is like a semi-plain, bounded by Lake Michigan. And the London region is flat expanse centered around the Strand. These “open” landscapes tend to generate a city with one main central business district, and residential rings around the core. But in Manhattan, these rings were more concentrated because the rivers blocked their outward expansion. As Manhattan moved north, and population and business density increased, land values rose more than it would have in a more circular city because economic activity was concentrated in a narrower band. This was the cause of Midtown’s rise as a skyscraper district at the turn of the 20th Century.

The Economic Roots of Midtown

After the First Inversion, the Madison Square neighborhood in the 1850s was a quiet well-to-do suburb, with townhouses lining the park, and with shops, theaters, and restaurants nearby. As the population continued its northward expansion, Madison Square became a central location for shopping and entertainment. Its continued popularity triggered a change in the 1880s. Clothing factories moved in to be close to the stores that sold their products. Insurance companies and banks moved in to be close to their customers. Townhouses were converted to hotels for tourists. The Broadway theater district was born. And so on. Soon the area around Madison Square was a bustling, heterogeneous district catering to consumers. Around the turn of the 20th century, the popularity of the neighborhood put pressure on land values, which then made erecting skyscrapers rational investments. Hence, the first skyscraper of Midtown, was the Flatiron Building at 23rd Street and 5th Avenue, giving birth to Midtown 1.0.

The Evidence

How do we know this? The evidence comes from an analysis of a data set collected about where people were living and working, and where businesses were operating, during the second half of the 19th century. New York, like many cities, annually produced directories, which listed the locations of people and businesses. Fortunately for researchers in the 21st century, the directories often listed both people’s residential and work locations, along with the nature of their employment. Other directories listed just businesses and their office locations. By collecting samples from these directories, we can follow the commuting patterns of people and the location decisions of firms. While more details are provided in my book or in my paper with Troy Tassier, the following graphs offer some evidence.

Commuting in the 19th Century

The maps below show the residential and employment locations of people who worked in finance, insurance, or real estate (FIRE), or who were listed as corporate officers, such as president, treasurer, or secretary (we call them Corporate Service Workers). The maps demonstrate several things. First, the residential locations (triangles) of these workers were steadily moving northward over the course of the 19th century. In 1861, there was a large residential cluster around Washington Square Park and the bulk of the residences was between Washington and Madison Squares. But, the vast majority of job locations (dots) was in lower Manhattan. The 1879 map shows a steady northward movement of this population with the majority now living between 14th Street and Central Park South. Job locations, by and large, remained downtown.

The bottom two maps (1892 and 1905–1906) show a similar pattern: the FIRE and Corporate Service Workers were steadily moving northward. By 1905–1906, a large fraction was living on the Upper West Side and the Upper East Side, between Central Park South and Central Park North. Employment locations remained concentrated in lower Manhattan, though by 1892, we see a large presence of these office workers in midtown, providing evidence that white collar workers were steadily moving northward, while white-collar jobs, by and large, remained in lower Manhattan, although there was a growing presence in midtown. Specifically, note the largest presence of midtown employment locations were in the Madison Square and Washington Square areas (about halfway between the southern border of Central Park and the southern tip of Manhattan and well south of the Grand Central neighborhood). This suggests that this area was the center of midtown commerce at this time.

Business Clusters

We can also look at the locations of specific companies. The top graph below shows the concentration of bankers and advertising agents relative to the lower tip of the island. For example, the graph shows that in the three periods surveyed—1866, 1882 and 1898—about 90% of bankers in Manhattan remained in the Wall Street area. However, over the same period we see something quite different for newspaper publishers and architects.

In 1866 and 1888, they were still strongly clustered downtown. But then note the “jump” in 1898. During the period from 1888 to 1892, a large fraction of companies in these industries moved from lower Manhattan to the area three miles north of the tip. This was around Madison Square, far south of Grand Central Terminal (another mile to the north). The key thing to note is that certain types of firms left midtown—those that were dependent on residential consumers for their businesses.

Newspaper Publishers at the Turn of the 20th Century

Newspaper publishers present an interesting example as illustrated by the movements of two of New York’s most famous dailies: the New York Times and the New York Herald. Originally, they both resided in lower Manhattan at Newspaper Row near City Hall. In 1890, the New York Herald left lower Manhattan to move to 34th Street and 6th Avenue. At the time, the Real Estate Record and Builders Guide wrote,

As regards the gathering of local news we should judge the Herald will have no little advantage over its contemporaries…The upper part of the city is alive and active till past midnight…The reporters will be able to undertake more assignments, and those which are given to them can be covered more quickly, and, in case time is pressing, with greater thoroughness.

Similarly, in 1904, the New York Times left its headquarters near City Hall to move to 42nd Street and Broadway. Its movement prompted the renaming of that area from Longacre Square to Times Square. In both cases, these newspapers felt that being close to the action was paramount—here the “action” was local news and events taking place in the city’s social, retail, and entertainment center.

The Rise of Midtown

To summarize, Midtown’s birth is due to the growth of consumer-oriented businesses around Madison Square after the Civil War. By the 1880s, a critical threshold had been reached where particular office-based industries found it profitable to move there to be closer to consumers. Once those firms moved, Midtown emerged as an office-based district. By the turn of the 20th century, land values had risen high enough so that skyscrapers were then profitable investments. This process unfolded at least two decades before Grand Central Terminal was completed in 1913. And, of course, access to bedrock played no role. During the Roaring Twenties, Midtown moved northward.

Myth Busting

The next time someone tells you that Manhattan has two skyscraper districts because of either access to the bedrock or Grand Central Terminal, please tell them these are just myths and misconceptions. And then you can share with them the real reasons presented in this blog series. While stories about the mighty forces of nature, or the ego-driven construction schemes by Gilded Age Railroad Titans, may help to make New York’s history more exciting, the truth about its growth is equally dramatic. New York City has always welcomed the strivers, who left their native countries to seek their fortunes. The skyline is the product of countless people—rich and poor—driven to build a home in the New World. Manhattan Island beckoned and they it made it so.

Continue reading Part I of this series here.

I would like to thank Maria Thompson for valuable editorial assistance.