Jason M. Barr January 2, 2018

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) recently issued its 2017 Year in Review for skyscraper construction around the world. As in prior years, the report has lead to a flurry of excited headlines. From The Times UK: “Taste for High Life Gives Rise to More Skyscrapers”; from ArchDaily.com: “The Results Are In: 2017 Was Another Record-Breaking Year for Skyscrapers,” and from CNN: “World Skyscraper Construction Hits All-time High.”

Implicit in these statements is that something is not quite right; that the world is being flooded with supertall structures must be due to nefarious, decadent, or irrational objectives. But, the truth, alas, is quite mundane. The increase in supertalls is a direct response to global economic growth.

This fact holds as true today, in the early 21st century, as it did a century ago. If we take a step back and look at the long history of skyscrapers, we can get a better perspective on when and where they are constructed. The first skyscrapers were built in Chicago and New York City starting in late-1880s as a way to accommodate the demand for office space in their respective central business districts.

The skyscraper was invented as a “machine that makes the land pay.” That is to say, land prices in New York and Chicago were so high at the time that developers aimed to build taller structures as a way to recoup the expense of paying for the land. However, the reason that land values were so high was that the Loop and Wall Street were booming at the end of the 19th century. These two cities were growing rapidly to accommodate the increasing trade and commerce that were contributing to America’s wealth.

The Threshold

Once a city or nation achieves an economic threshold, it then has the resources and economic demand to build a skyscraper. Technological progress over time makes the definition of “tall” creep up, but the logic of tall has not changed. It emerges from the supply and demand calculus. Increasing business, trade, and urbanization draw people to cities. Because of the strong forces of agglomeration, some locations become very valuable. This then incentivizes developers to build tall, which further increases the value of these central locations, increasing demand for more skyscrapers.

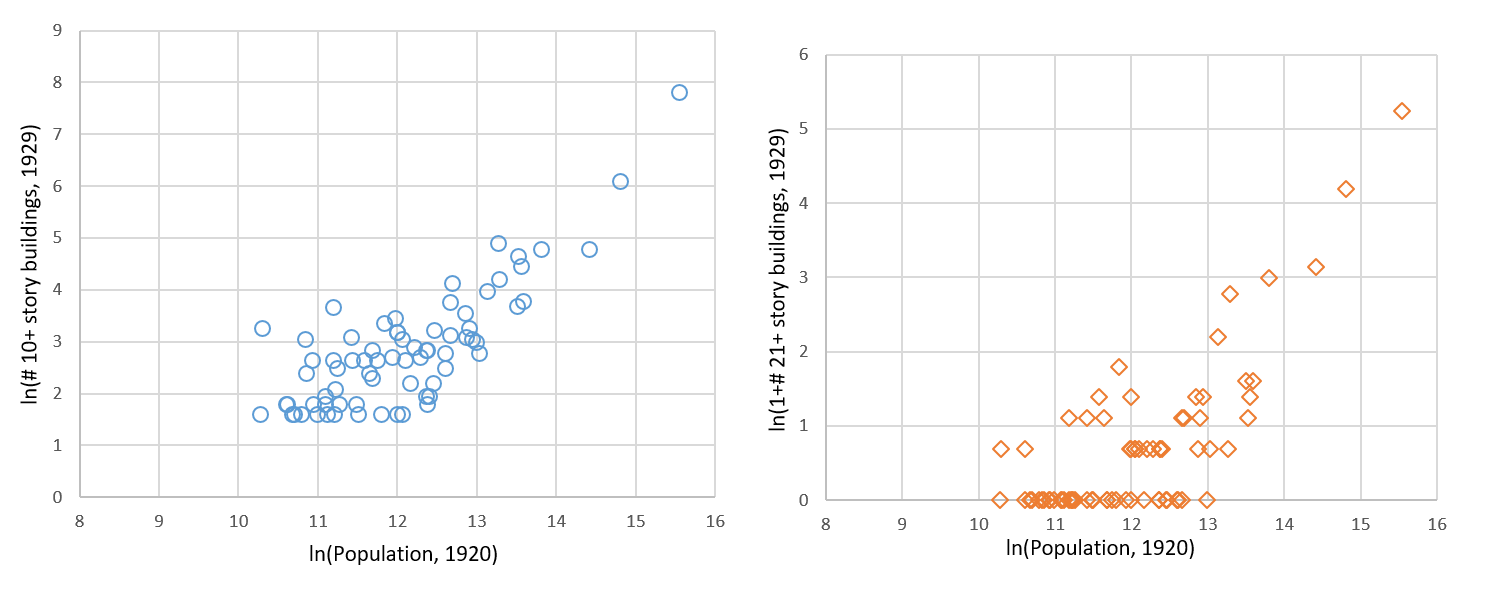

We can see this in America in the early 20th century. Figure 1 shows, for 72 cities, large and small–from Albany to Youngstown–the relationship between a city’s population and the number of tall buildings it hads. The left graph shows the number of structures that are 10 stories or taller in 1929 versus its 1920 population; the right graph shows the number of 21-story or taller structures versus its 1920 population (all variables are in natural log format).

While the relationships are not one-to-one, it is clear that larger, more productive cities have more tallr buildings (the same would be shown with each city’s gross city product, but I could not find such data). On average a 10% increase in population lead to having an 8.6% increase in the number of 10-story or taller buildings. Furthermore, a 10% increase in population increased the probability of having a 21-story or taller structure by 2.5 percentage points. Once a city’s population hit about 315,000 there was a 100% chance it had at least one very tall structure (except for Washington DC, which had strict building height laws).

That was nearly a century ago. Let us scale this up to nations today. Barely any poor countries have skyscrapers. North Korea, which has been trying to finish the Ryugyong Hotel since the late 1980s, stands as a monument to the exception that proves the rule. Skyscrapers, rather, emerge in rapidly growing countries.

Not every rich country embraces skyscrapers—there are none in Norway or Denmark, for example—but again they are the exceptions. By and large, most rich countries find they have a need for them. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the number of 150-meter or taller buildings in 177 countries versus their respective GDPs (again in natural log format).

The figure strongly suggests that there is a threshold, here about $34.5 billion, which, once passed, leads to more skyscrapers. Once hit, there is very strong relationship between the size of an economy and the number of skyscrapers. In fact, on average, across countries, a 1% increase in a country’s GDP leads to a nearly 1% increase in number of skyscrapers.

The Global Growth in Skyscrapers

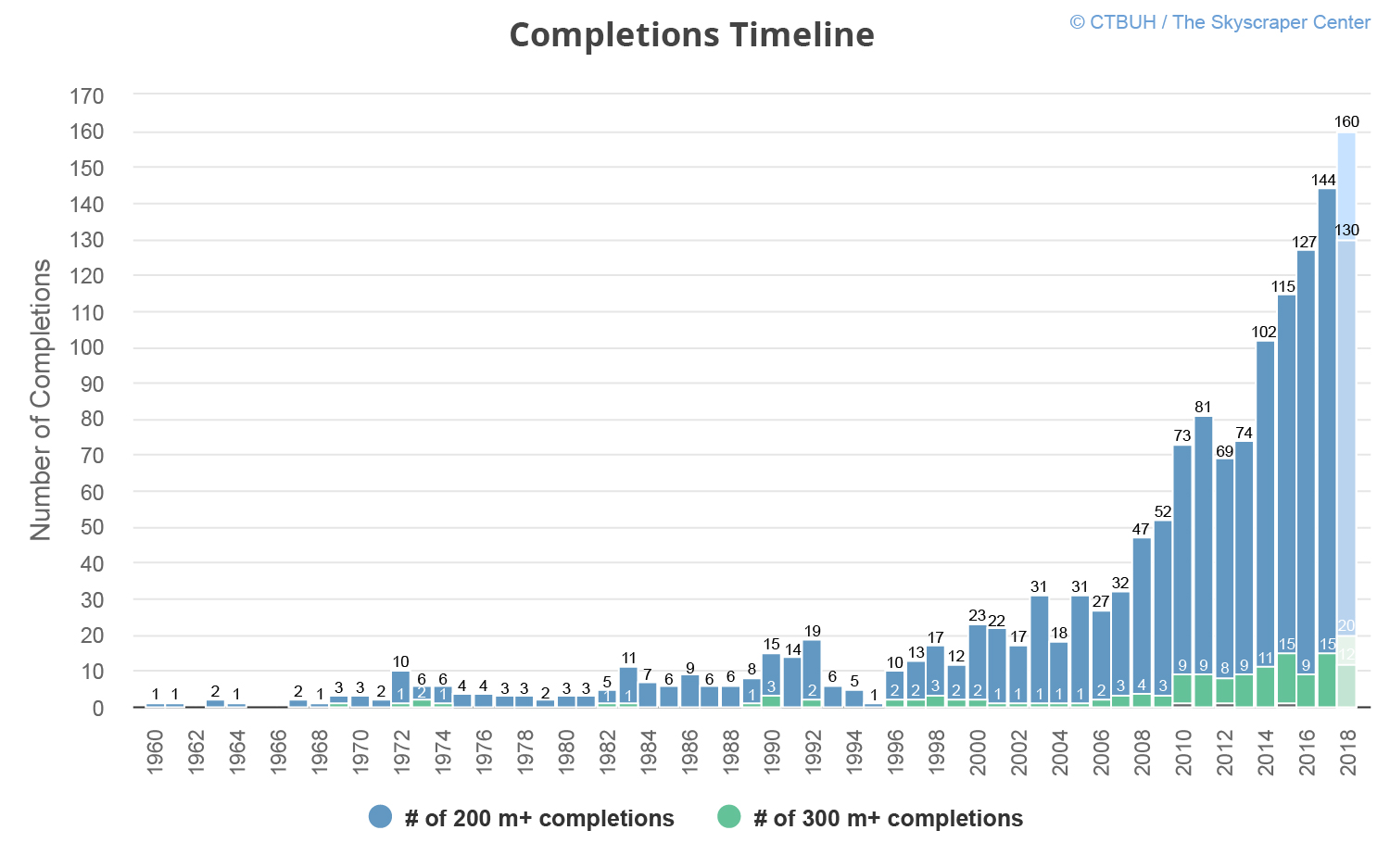

We can, in fact, zoom out one step further and look at this from a global perspective. Imagine that planet earth was one country. We can look at how the total number of skyscrapers completed on the planet each year is affected by global income growth.

To this end, I collected data on the number of tall building completed each year since 1960 (where here a tall building is one that is 190 meters or taller), and three other important variables: global gross domestic product (GDP), global population, and the fraction of the human population that lives in urban areas. I have created detailed notes on the data sources and analysis for the interested reader.

In short, global GDP, population growth, and urbanization can account for 92% of the variation in the number of skyscrapers completed each year. In other words, these three variables are the key to understanding why tall buildings are becoming both more numerous and taller. I find that, at the global level, a 1% increase in global economic growth leads to a more than 1% increase in skyscrapers, on average.

In 1960, global GDP was $11 trillion; today it is $72 trillion. What’s more, since 1960, global GDP has only declined in one year (in 2009 after the Great Recession). This is worth stressing again: despite the ups and downs of national economies, such as that of the U.S. and those in Europe, planet earth, as a whole, has experienced a rise in incomes every year for the last 56 years, save one. Each year that the world increases its income means that it will continue to add more and more skyscrapers.