Jason M. Barr August 23, 2018

[Author’s note: This is the second of at least two blog posts about Jane Jacobs and her book, The Death and Life Great American Cities. The first one can be read here.]

The Visions of Saint Jane

In 1961, Jane Jacob published her seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In it, she decries large-scale interventions by the government, and promotes small-scale ideas to create diverse and vibrant neighborhoods. She believed in the power of the people to naturally bring order to the bustling city. Since then, Jacobs has become the Patron Saint of Livable Cities. Her book serves as a kind of the bible for the movement.

Jacobs’ main argument is that the best neighborhoods have several key elements. They have mixed uses; contain mostly low-rise buildings of various ages; foster walkability; and are active 24 hours a day. Her appeal is seductive because she offers people a better way to live, beyond the stultifying suburbs or bland city neighborhoods built after World War II.

The Chaos Revolution

I would like to argue, however, that her words have never been, nor likely will ever be, truly applied in full. To implement them as she describes would be nothing short of revolutionary—a revolution that most people, even her followers, would not care to see to fruition.

As I discuss in another post, Jacobs had a libertarian streak. She protested against the big schemes of government, and felt that, with a limited number of policy and planning tweaks, a neighborhood could reach its true potential. But these tweaks were mostly about nudging people into achieving their personal ambitions. They were about establishing the institutional framework for the actors (or “ballet dancers”) to go about their own business, with few rules on what they could or could not do, including with their property.

In essence, Jacob’s philosophy was that of letting go—of removing barriers and restrictions—and allowing the people and the market to decide the best outcomes. When maximum freedom is permitted, the neighborhood becomes like the trust fall game—if you let go and lean back, the neighborhood will catch you. The mothers will look out for each other’s kids, and the shopkeepers will be the guardians of the street. But you must let go; you must let the chaos of daily urban living take hold, and from out of this chaos, order and peace will naturally emerge.

Letting Go

Today, the world that she envisioned—the one she lived in on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village circa 1960—is no longer appealing to the majority of parents with young children (if it ever was then). Actually, it is actually quite frightening. In this world, kids are to have the run of the city. They are able to be out on the streets at any time, with the freedom to zoom from the playgrounds to the stoops, into and out of the shops, and to roam the alleys and byways of the city.

The streets are to be noisy with the sounds of life: the marching of workers to their jobs; the hawking cries of street vendors; and the jukebox music oozing from the honky tonk joints. In the early morning, the wind will radiate the fragrance of fresh bread baking in large industrial ovens; while in the evenings, the smells of a thousand roasted chickens emanate from a thousand apartment kitchens.

Neighborhoods must be open to all comers. Floors or buildings must be freely converted into shops, bars, factories, breweries, apartments, or whatever the economic demand draws forth. It is a place where moms take their infants out in strollers in the morning, laborers with lunch pails fill the streets during noon; kids run wild after school; locals do their shopping in the afternoon; while at night, the interlopers arrive to drink down a few beers or to listen to live music. The cycle is repeated day after day.

In short, this world requires two key elements: children must have the run of the streets (and sidewalks), and there can be very few restrictions on the kinds of economic activity and people in the neighborhood. I ask you: Are you ready for this where you live?

Birth of the Nimby

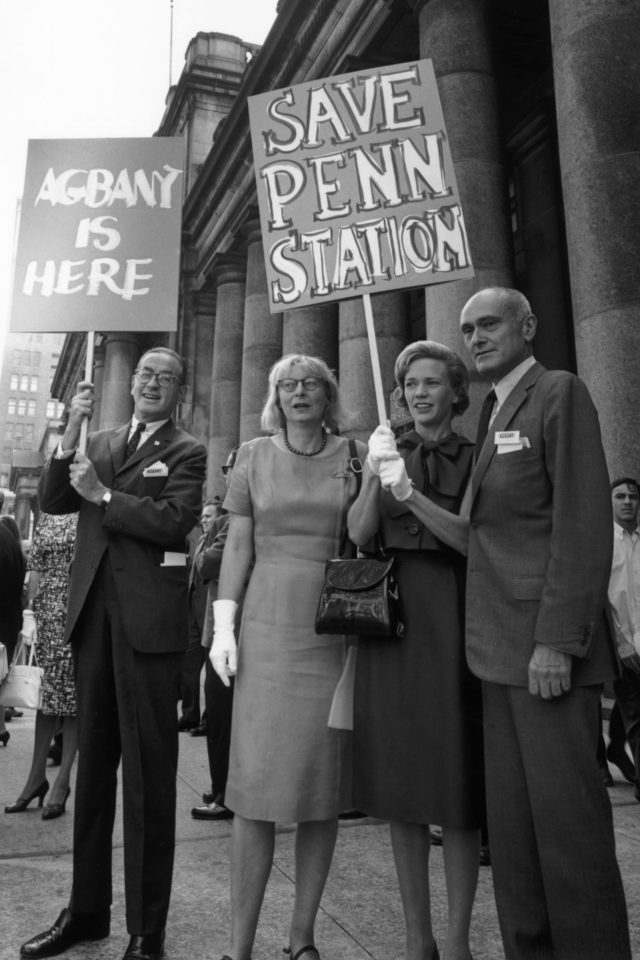

Like all good prophets, Jacobs’ words were just specific enough to engender a movement, but not so much so as to remove room for interpretation. As a bible of livable cities, her book offers both the proscriptive and the prescriptive. The forbidden commandments are the ones related to “Thou shall not allow large-scale government projects”: no slum clearance, no public housing projects, and no freeways in the heart of downtown. The paternalistic plans of city officials destroy vibrant neighborhoods and replace them with monotony, crime, and hopelessness. Saint Jane gave people the encouragement and justification they needed to stop the Robert Moseses of the world, and to prevent the demolition of beloved landmarks and neighborhoods.

This is all well and good. Self-determination is an important right. But the next step, according to Saint Jane, is to implement the prescriptive rules—a series of limited actions that local governments should take to foster diversity. These include shortening city blocks and widening sidewalks; voucher-like programs to encourage the private development of low- and moderate-income housing; fostering buildings of various ages, sizes, and heights; and constructing civic buildings within the urban fabric, rather than in isolated barren plazas.

These policies, on the surface, seem easy enough to implement. But they are just the superficial elements of true Jacobsism. It’s easy to pay lip service to them because few are opposed to things like wider sidewalks. But to do as Jacobs commands means relinquishing control to the chaos of dense urban life—something residents today have neither the desire nor the incentive to do.

Retaining Control

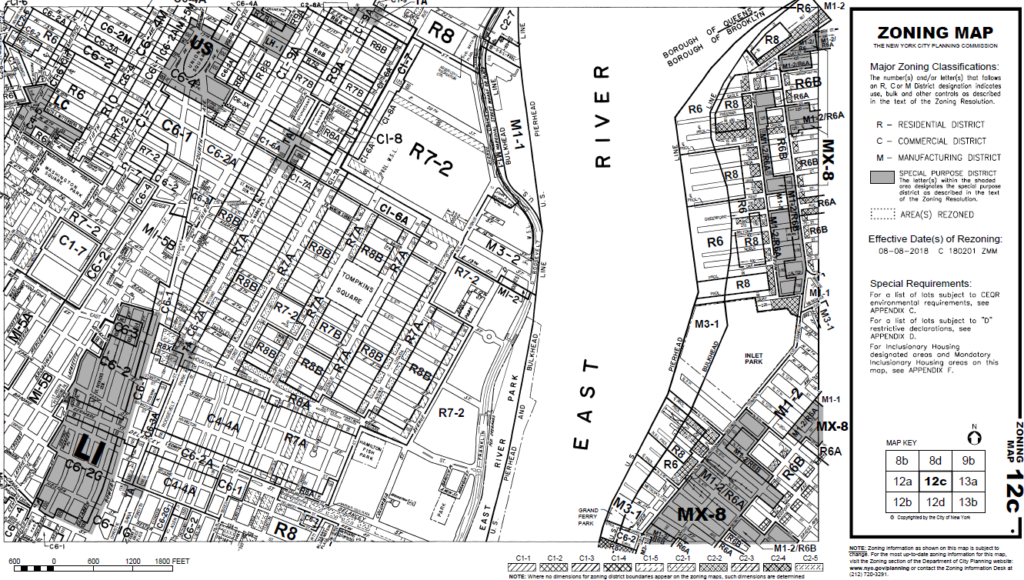

Over the years, they found that imposing the “Thou shall nots” was a successful strategy for keeping sweeping changes out of their neighborhoods. But the residents also found they still needed government to enforce the control they really wanted. For this, they turned to zoning: the set of land use rules that state, often in minute detail, what is and is not allowable on every lot in the city. Factories pollute and must be kept away; the children must be safe from strangers; noisy bars must be shutdown; and property values must be protected. By creating these restrictions, zoning became the weapon of choice to maintain order.

But the reason that Jacobs’ ideal neighborhoods like Hudson Street and the North End in Boston succeeded was because people never had “control” in the first place. They settled there because they offered cheap housing close to employment and immigrant enclaves. As people poured in, the real estate evolved to supply the different things that the residents needed, be it apartments, shops, or employment in factories.

Their success was maintained because the families stayed even after they had the income to move. They likely remained because of the amenities and cultural connections, and because their neighborhood cohesion allowed them to block the government bulldozer. But once they organized and told the world that they are the Temples of Saint Jane, it was all over. They took control and implemented controls. And that was that.

Saint Jane Lite

Yet through zoning and preservation to stop neighborhood changes, residents could argue they were following the Commandments of Saint Jane, even though they were demanding something she did not prescribe. It’s true that Jacobs opposed rapid change in a neighborhood’s features, but this was because she felt it uprooted people too quickly and sped up the loss of diversity. Her objective was to slow change in order to prevent homogeneous land uses, and to allow the city streets to provide their natural order. But this has been interpreted, for example, to mean that Greenwich Village should essentially be frozen in time and place.

To many, zoning and preservation offers Saint Jane Lite—a hybrid program of keeping government from tearing down neighborhoods, while also preventing its evolution. As a result, Jacobsism has morphed into giving new prescriptions meant to preserve the status quo and offer nominal gestures to her book without having to implement her philosophy full-scale, such as widening sidewalks, or limiting ground floor leases to only mom and pop shops.[1]

Goldilocks and the City

Another movement—the Goldilocks Density movement—has risen up as an offspring to Jacobsism. Its adherents promulgate high population density, but relatively low building density. Ideal examples include many neighborhoods in Paris and in New York, such as Greenwich Village and Washington Heights.

Population density is good for all sorts of reasons, including lower CO2 footprints, more social interactions, healthier lifestyles, and so on. The Goldilocks Density movement, however, does not negate my point. First is that the Goldilocks folks often make common cause with the preservationists who seek to stop neighborhood change in central cities. Second is the issue of letting go. Turning a low density suburban neighborhood into one with apartment buildings and greater walkability can be a good thing. But it will not change how people feel about controlling their neighborhoods. Residents will not go gentle into that good night when it comes to zoning.

Out of Chaos Comes Order?

I want to be clear that I support greater urban density, mixed-use neighborhoods, and walkability. Furthermore, I agree with many (though not all) of the sentiments put forth by Jacobs in her book. But her words are only as good as they are interpreted, and her teachings have been used to justify something that I do not think she ever intended.

In the end, what do we get from Saint Jane Lite? A lot of “Thou shalt nots,” a housing affordability problem, high economic and demographic segregation, and rising income inequality. This is not what the prophet ordered.

—-

[1] In in her book, Jacobs complains about people misunderstanding her ideas. She describes how she was frequently approached by developers gleefully telling her that they left room in their projects for the corner grocery story. Yet, she laments, that this was beside the point. To create vibrant neighborhoods meant more than checking a box for the Mr. Hoopers of the world.