Jason M. Barr January 31, 2018

As the income of Planet Earth continues to rise, the construction of tall buildings proceeds apace. Many cities around the world are increasingly housing their residents in highrises. Skyscrapers are seen as way to provide shelter to growing urban populations without resorting to sprawl and which can potentially provide more park space, and other urban benefits.

In China, for example, the economic reforms instituted in 1978 have unleashed the greatest internal migration in world history. Millions of rural residents have moved to cities seeking employment in factories and the growing service sector. The city of Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta was mostly farmland in 1980 and today is one of the world’s largest cities.

In the United States, large cities, like New York and San Francisco, suffer from affordability problems; highrise construction offers a possible solution, as well as opportunities to make these cities more resilient against climate change.

Though highrise living can provide benefits to societies across the world, it begs the questions: what is it like to live in one, and is the experience positive or negative? Here, I aim to focus on one particular angle—the psychological dimension.

The Perceptions of Highrise Living

The perception in the United States about highrise living is decidedly mixed. On one hand, living in skyscrapers is seen as a status symbol. That one could afford to live in luxury apartment building in New York, Chicago, or San Francisco suggests power and status. As income inequality rises, tall living is increasingly used to show off wealth.

On the other hand, experiences in public housing projects have driven the perception that tall buildings for the poor are an unmitigated disaster. The Pruitt-Igoe complex, completed in St. Louis in 1956, looms large in the public consciousness. The segregation and concentration of the urban poor into the housing complex, combined with mismanagement, created an even worse environment than the old tenements they replaced. All 33 buildings—each only 11 stories—were demolished in the mid-1970s.

The Consequences of Highrise Living

In 2007, Professor Robert Gifford of the University of Victoria, published an article, “The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings,” in the journal Architectural Science Review. Dr. Gifford’s interest was to review the literature on the psychological impacts of tall buildings on their occupants. His manuscript surveys nearly 100 studies that investigate whether highrises improve or diminish well-being and mental health.

Each study focuses on answering a question about whether tall buildings increase or diminish one of the following dimensions: housing satisfaction, psychological stressors (“strain”), suicide, behavior problems, crime and fear of crime, positive social relations, or helpful child rearing.

Dr. Gifford’s literature survey appears to be, if not exhaustive, then representative of the field up until 2002. Given this, I performed a kind of meta-review of the articles by grouping the listed studies into one of three categories, based on his description of each one.

First is the “positive” group, where a study concludes that highrise living offers some positive outcome in people’s lives. The second is the “negative” group, where highrise living is found to make residents lives worse off in some respect. Third is the “mixed or neutral” category, where the results suggest either a benign outcome, or both positive and negative outcomes.

The Findings

The results were not encouraging. Of the 99 studies reviewed, only 17 measured a positive outcome for the research question; 55 measured negative effects, and 27 were mixed or neutral. Across these different categories, a large number of studies found that people living in highrises suffer from greater mental health problems, higher fear of crime, fewer positive social interactions, and more difficulty with raising their children.

For example, on highrise living and depression, Gifford writes:

More serious mental health problems have tenuously been related to building height. In an English study, mothers who lived in flats reported more depressive symptoms than those who lived in houses (Richman, 1974). Rates of mental illness rose with floor level in an English study (Goodman, 1974). Psychological symptoms were more often present in high rises (Hannay, 1979).

And on child rearing, he concludes:

The problems range from fundamental child development issues to everyday activities such as play. For example, a Japanese investigation (Oda, Taniguchi, Wen & Higurashi, 1989) concluded that the development of infants raised above the fifth floor in high-rise buildings is delayed, compared to those raised below the fifth floor. The development of numerous skills, such as dressing, helping and appropriate urination was slower. Children who live on higher floors also go outside to play less often (Nitta, 1980, in Oda et al., 1989).

The Caveats

Certainly, there is much to be concerned about. However, several caveats must be applied to the overall conclusions from the article (and which are discussed in Dr. Gifford’s article). First is that the bulk of the research has studied highrise living in declining U.S. cities in from the 1960s to 1980s in public housing projects. Public housing was an attempt at both social engineering and government provision of affordable housing. The Federal government required that the housing was only for the poorest of the poor and encouraged racial segregation.

If you study occupants in Pruitt-Igoe, for example, how much of what you are seeing is from the nature of the height of the building itself versus other architectural aspects? Or how much comes from the much larger, and potentially more serious, issues of the extreme concentration of poverty in isolated urban pockets, where jobs are declining, educational opportunities are lower, and racism rears its ugly head?

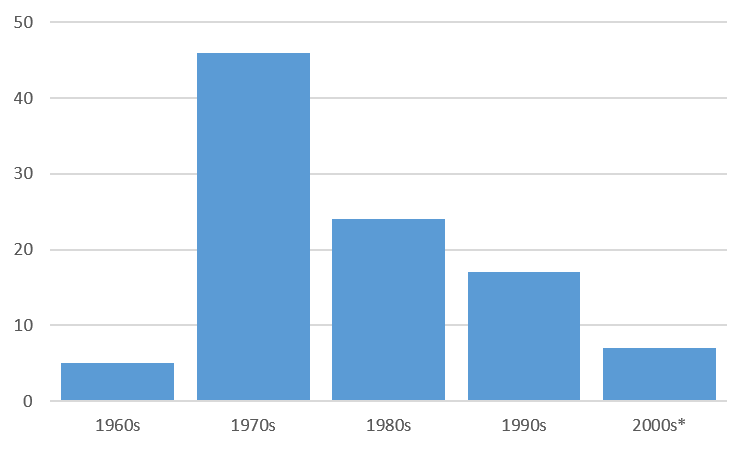

In fact, a review of the publication dates of the studies shows that the 1970s was a Golden Age for research on the psychological impacts of highrise living, just when the United States was realizing the horrible mistakes it made in its public housing policies. Now that many cities have stabilized their populations and reduced crime and urban blight, it is time to revisit the effect of building form on well-being. The increasing use of big data also offers tools not available in the first big wave of tall building research.

Disentangling Cause and Effect

Furthermore, the discovery of cause and effect between housing design and measures of psychological well-being is particularly challenging. People feel strongly about the kinds of housing they want, and, in general, they cannot be randomly assigned for experimental reasons. Randomly provided housing may engender a feeling of loss of control, which can diminish how they feel about that particular housing and about themselves.

As Professor Gifford points out, those groups subject to random assignment, such as members of the military and college students in dorms, are unrepresentative of the larger urban populations that we seek to understand. They know their housing is temporary and expect random outcomes as part of their personal experiences.

More broadly, when trying to tease out the effects of highrise living, we need to know how people acquired their housing in the first place. If public highrises, for example, are the most readily available form of cheap shelter, it may be that people chose to live in them, despite not preferring to be there. If lower income people have a higher proportion of mental health issues, then one might not able to disentangle whether highrise living was the cause or the effect of a particular problem.

Towards a More Livable Highrise

Despite these caveats, the literature on happiness and urban design, as well as the lessons learned from public housing, offer knowledge and experience for making cities more livable. Highrise living doesn’t need to be for everyone, but the key point is that, for many people, residing in the central city or close to transportation hubs, jobs, and urban amenities is important. A way to allocate these valuable locations is to build taller. Yet, if highrises are built only for the wealthy it contributes to the gentrification of neighborhoods and the loss of opportunities for those with lower incomes.

Dr. Gifford’s literature review also offers a useful guide to the things that are important to residents or that can promote suffering if not eliminated. People’s happiness and mental health depend on not only what happens in the street, but also what happens inside their residences, as well as the liminal spaces between street and residence.

First is a feeling of safety, as no one wants to live in a building that encourages criminal activity or violence within the structure. Just as importantly, is that people want their buildings or neighborhoods to foster positive social interactions—to have both a sense of community and social support in times of need. Children need access to play spaces, and other children. Residents also require proximity to nature and greenery.

Building the Future

Architects, engineers, and developers must work with government officials to find rules and inducements that can create highrises that satisfy people’s needs. Take child rearing, for example; as discussed above, many studies have shown that children have a harder time in highrises, presumably, because, by living higher up, they are farther away from the things they need for healthy development. Problems like this, through good design, could be mitigated, such as having community and play rooms spread throughout the building or encouraging mixed-use buildings that have schools and child-friendly resources on the lower (or upper) floors.

There is a growing awareness among real estate professionals that highrises need to provide not only shelter but also promote mental health and helpful social interactions. Architects are also trying to bring green spaces up into the buildings themselves. There is a nascent “greenwalls” movement, where plants and trees are attached to the facades of structures. The question becomes how to apply this technology across the income spectrum.

The aim of social science is not only to disentangle cause and effect, but also to learn from human actions and policies that worked and did not work. That the government’s experiences with the Projects backfired does not mean we should give up on public and/or highrise housing for lower income residents. Nothing is more important than housing that promotes good mental health, and we have an obligation to learn from our mistakes and make sure they don’t happen again.