Jason M. Barr and Ronan C. Lyons October 22, 2025

The citizens of New York City are gearing up to pick a new mayor. On one side stands a candidate riding a wave of anger among those struggling to pay the rent and make ends meet. Realizing that land is at the heart of the city’s political economy, this candidate is promising to break the grip of entrenched property interests.

Lined up to oppose him are the traditional business elites. Wary of a program that could upend–they would argue–the city’s economic success, the establishment is using its significant institutional resources to back a perceived moderate Democrat. At the same time, the Republicans spot an opportunity to win amidst a split electorate.

But wait, what year are we talking about?

On the one hand, we could be talking about the 2025 mayoral election with socialist candidate Zohran Mamdani, who is leading in the polls against former Governor and Democrat Andrew Cuomo and former Guardian Angels leader and Republican Curtis Sliwa (with incumbent Mayor Eric Adams having recently dropped out due to his widespread unpopularity).

On the other hand, the year could be 1886, when Henry George, running on the United Labor Party ticket, campaigned on a radical platform of reforming how real estate should be taxed. He ran against the establishment, though pro-reform candidates, Democrat Abram Hewitt and Republican Theodore Roosevelt. Losing in his first bid, George ran again for mayor in 1897. However, he died of exhaustion just days before the polls opened.

In both campaigns, George ran on what he called the single tax platform—reforming real estate taxation to be fairer to workers and to encourage urban growth.

Perhaps it’s time to revive his campaign.

History Redux?

There are fascinating connections between the current race and the one from fourteen decades ago, especially regarding real estate taxes. Today, the press is abuzz with speculation about what Mamdani will do if elected. One such headline wonders, “Real Estate tax system in New York’s property tax system is broken. Could Zohran Mamdani fix it? The piece writes,

A number of housing advocates and even landlord groups have speculated in recent weeks that a Mamdani mayoralty could finally force action on the city’s property-tax system, which is widely acknowledged to be broken. The infamously complicated 50-year-old structure generally overtaxes large multifamily rental buildings and homeowners in working-class neighborhoods while undertaxing homes in gentrified areas like Park Slope and the East Village, as well as expensive condos and condominiums.

Henry George and the Land Tax

Born in Philadelphia in 1839, George left school at 14 to work as a clerk at an importer, which allowed him to travel to Australia and India. He hoped to strike it rich during the California Gold Rush, but arrived too late. He then had a checkered career as a journalist, editor, and publisher throughout the 1860s and 1870s. However, he was a lifelong autodidact, especially in economics. In 1879, he published his classic work, Progress and Poverty, which argued that a key source of economic hardship for the working class was the existence of private property.

George witnessed land speculators buying vacant or under-utilized lots—doing nothing with them—and flipping them for considerable profit. Thus, in his view, the speculator was a kind of leech, benefiting from the actions of others—from neighbors and city residents more broadly—who were increasing land values, no thanks to the speculator.

As George argues,

Here is a lot in the central part of San Francisco, which, irrespective of the building upon it, is worth $100,000. What gives that value? Not what its owner has done but the fact that 150,000 people have settled around it. This lot yields its owner $10,000 annually. Where does this $10,000 come from? Evidently from the earnings of the workers of the community, for it can come from nowhere else.

The Land Value Tax

George’s solution to the “speculator problem” was the Land Value Tax (LVT), also called the Single Tax. In George’s view, the value of the structure on the property would not be taxed at all. The entire tax bill would be based solely on the land value. In his radical position, he felt that the government should tax 100% of the land’s annual value, generated by the $10,000 in income per year in the example above. In George’s view, this was akin to abolishing private property, since the income that produced that value would be fully taxed.

There were two reasons why taxing the land at 100% would be a benefit to society. First, as he states, is that

Land is not an article of production. Its quantity is fixed. No matter how little you tax it there will be no more of it; no matter how much you tax it there will be no less. It can neither be removed nor made scarce by cessation of production. There is no possible way in which owners of land can shift the tax upon the user.

In other words, taxing land does not distort the economic incentives for production and construction, since land is a fixed and finite resource; if you tax it, there will be no reduction in what’s offered up for productive use. Unlike more mobile forms of wealth–which can flee to tax havens if given the incentive and opportunity–the acres of Manhattan aren’t going anywhere.

Second, since the community creates the land’s value, taxing it will return the resources to the community rather than to the “greedy” speculator.[1] As George writes,

A tax upon the value of land is the most equal of all taxes, not that it is paid by all in equal amounts, or even in equal amounts upon equal means, but because the value of land is something which belongs to all, and in taxing land values we are merely taking for the use of the community something which belongs to the community, which by the necessities of our social organization we are obliged to permit individuals to hold.

Penalizing the Space Invaders

George’s ideas still have wide currency. Rather than taxing away the entire land value, Georgists aim to reform the real estate tax system in a less dramatic manner. With the current real estate tax system, the tax is effectively a tax on two different assets, since it applies equally to both the land and the structure built on it. An increase of $1 in the value of either the land or the building will increase the tax bill in the same way.

For example, let’s say you add a room or suite to your house so your aging parents can live with you. The land value will not change, but the property value will rise because your home is now more valuable. Your tax bill will go up as a result, and you have just been penalized for doing something nice for your family. As a result, landowners are disincentivized from redeveloping or improving the structures on their land because doing so comes with higher taxes. Seen this way, it is perhaps unsurprising that the LVT has strong support among economists because of what George argued. Taxing the land’s value

- will not reduce the amount of land offered up for productive uses,

- is a way for the community to pay the tax and receive the benefits more fairly, and

- will disincentivize land owners from holding under-utilized land or failing to redevelop it to its most productive use.

A property owner’s tax bill will be proportionally less if the property is developed according to its highest and best use and therefore generates more income that can help offset the land tax. In policy circles, the most common proposal is a split-rate system that assigns relatively higher rates to the land’s value and lower rates to the structure’s value. But even a single tax on the land value could, in principle, generate the amount of revenue the municipality needs to run its operations.

Taxing the Apple

New York City follows the standard real estate tax practice of equally taxing both the land and the building’s value. But if you wade through the system of how the tax bills are determined, it’s clear that the current tax system is a mess, incredibly (and needlessly) complex. Different types of properties are valued and taxed differently, and then there’s a whole host of abatements and exemptions. The complex and byzantine nature of the property tax is a result of politics—the municipality needs to raise as much funds as possible from the real estate tax without angering voters. Therefore, the City has developed a system so arcane that it obscures the unequal and arguably unfair impact on its residents.

Assessing the Situation

The taxing process starts with an estimate of the market value of each property, which is the combined value of the land and structures. Then, based on a specific formula, the city determines the Assessed Value (AV) for each lot, which is a fraction of the market value used for taxation purposes.

For smaller homes (three units or less), the AV is 6% of the market value. For all other buildings, it’s 45% of the market value. However, because market values (and AVs) can be volatile, the law limits how much the market value can be increased for tax purposes.

In other words, the City phases in increases in AVs to create a “billable AV,” which is necessarily less than the actual AV. In addition, many properties also qualify for exemptions, which remove some fraction of the AV from being taxed. About one-third of all properties have a partial exemption; about 4% of all properties have a 100% exemption, such as those owned by religious institutions, the government, or educational institutions.

The City then produces four different tax rates for its four designated property types or classes. Class I are homes with three or fewer units.[2] Class II are apartment buildings, and condo and coop units. The third class covers utilities (such as electricity, communications or rail infrastructure), while Class IV covers commercial properties. The respective tax rates are applied to the net billable assessed values (total billable AV minus the exempt portion).

Still with us? Then there’s a suite of abatements that are applied that reduce the tax bill further, if you are fortunate enough to qualify for the abatements. These abatements reduce the property’s assessed value. In particular, the now-elapsed 421a tax abatement program gave substantial tax deductions for new multifamily construction.

Switching to a Land Value Tax in New York City

So far, so complex. But could it be simpler and fairer? This leads us to the key question: Could a land tax work in New York City? And if so, who would win and who would lose under such a scenario?

To answer these questions, we need to make some simplifications.

- We start by assuming that this exercise is “revenue-neutral,” i.e., the new LVT would need to generate the same income as before—the $36.9 billion that the City projects to get from the property tax.

- Secondly, as we indicated above, there would be zero taxes on all buildings (“improvements”). Only land values would be taxed.

- Third, we assume that every property owner pays the same rate. The City moves to one tax rate and not the four that it has now.

Other than the rate, however, almost all of the City’s current property tax system, in terms of existing land values and exemptions, would be maintained. We aim to change the basis by which those who pay do pay, not to iron out features of the system that have emerged over decades. So, we use the current land market values as determined by the City, and the taxable land is the value after removing the fraction that is exempt. For example, if a lot is 100% exempt, then no taxes are paid.

To calculate the tax rate, we take the total tax levy needed ($36.9 billion) and divide it by the total net market value of all property in Gotham. Using New York City’s figures for FY2025, the total market value of the city’s land comes in, conservatively, at $412 billion.[3] But nearly one-third of that land value is exempt from taxation.[4] Removing the exempt portion gives a total land value of $294 billion. That means, to generate $36.9 billion in revenue, the land tax rate would be 12.55% of the market value.

The Outcome

Thanks to the rich data sets available from the City, we can go a significant step further and estimate how much each landholder’s tax bill would change as part of this switch. (Sources and analysis are here.)

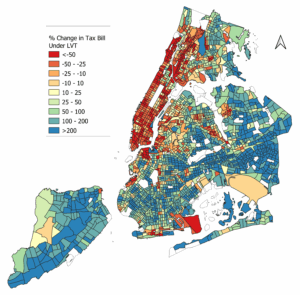

To make it easier to spot patterns, we jump up to the census tract level. For each tract, we added up the total tax bill under the current system and compared it to the total tax bill under the LVT. Figure 1 below shows, by census tract, the percentage increase or decrease from current payments.

Doing this highlights who is keeping the current system “afloat,” by paying higher taxes than would be the case if land, only, were taxed. The picture that emerges is clear: Manhattan, the western Bronx, and neighborhoods near the East River in Queens and Brooklyn “float” the rest of Gotham. Their tax bills would go down significantly if New York switched to a single LVT from its current system.

According to our estimates, under this scenario, just under one-third (29%) of tracts would pay less or no more under a move to LVT. The burden of the current system is falling on a relatively small set of areas. By contrast, almost half (46%) of Census tracts would have to pay twice as much, or more, in property tax under the LVT (not, of course, what outer borough New Yorkers want to hear).

The Grand Concourse

Take two examples. In the map above, the red north-south strip in the Bronx, just north of Harlem, is the Grand Concourse neighborhood. The Grand Concourse is a wide boulevard lined with middle-class five- and six-story apartment buildings. Built up before the Great Depression, the neighborhood was designated a historic district in 2011 for its many fine examples of residential Art Deco architecture.

Today, it is a vibrant working-class neighborhood, about two-thirds Hispanic and one-third Black. However, its median household income is about $40,000, about half the citywide figure. Under the LVT, the neighborhood would see a substantial reduction in property taxes, First, it is relatively dense, with about 112 people per acre (as compared to 46 people per acre for the entire city). Second, because the current scheme “overtaxes” apartment buildings, residents now are paying relatively more than they should.

Queens Community District 9

On the other hand, take the central Queens region of Community District (CD) 9, which includes the neighborhoods of Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Woodhaven. It’s a very diverse neighborhood, and most of the residents are foreign-born. About a quarter of the population is Asian, 37% Hispanic, and 20% White.

Its population density is relatively low at 44 people per acre, with nearly 99% of its buildings being three stories or less. 75% of its structures are one- or two-family homes, with a homeownership rate of 50%. The median household income is over $100,000, about 20% higher than the city’s median household income. Despite its low density, there are subway lines running through the district, as well as a Long Island Railroad stop in Kew Gardens.

Thus, given the great transportation access, the relatively high income, and the high proportion of low-density housing, the neighborhood would see a large increase in its tax rates under an LVT scheme, as the current tax scheme “rewards” one- or two-family owner-occupied neighborhoods.

A Taxing Situation

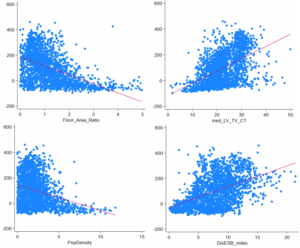

More broadly, the reason those in the “blue regions” in the map above would have to pay more is that they are relatively low-density neighborhoods. In places that have mostly apartment buildings, the land value share is relatively lower compared to the total value. In short, to make property owners whole—that is, to have them pay the same tax as before—would require densification of their properties by adding more units.

For example, the figures below show that the CTs with the lowest densities, on average, would have the greatest increases; in many instances, a doubling or tripling of CT building densities would be required to prevent the average resident from paying higher taxes.

What We Learned from this Exercise?

This exercise shows that a land value tax system is not just a theoretical possibility. We can adjust the current without much difficulty because the City already calculates land values, and the overall high value of its land makes it possible to design a program that is revenue-neutral. The exercise also shows that higher-density areas would see their tax bills decrease because they are using the land more efficiently.

The intent of the LVT system is that by taxing only the land values, residents are not penalized for adding new housing. However, this introduces a new issue. Implementing a land tax would “turn up the heat” on those holding under-utilized land. However, New York’s zoning codes prohibit this redevelopment. By our estimate, nearly half of the residential buildings are either above the allowable floor area or within 33% of it. In other words, densification is prohibited by law or severely restricted for half the residential lots in the Big Apple!

Thus, if New York really wants to make housing affordable, hand in hand with making the property tax system fairer, it needs to substantially reform its zoning to allow for greater densities in the outer boroughs. Based on our analysis, this would mean allowing low- and mid-rise apartments near transit hubs and allowing for garden apartments and denser housing types, like “triple deckers,” in the most suburban neighborhoods. While the recently passed City of Yes Housing Opportunity upzonings are a good start, more needs to be done.

The land tax does not necessarily mean the end of the single-family home in New York. But it does mean that single-family homeownership will become more expensive relative to other forms of housing.[5] Even the creation of an accessory dwelling unit (ADU), such as converting a garage to a rental property, can go a long way in reducing the tax bill increase when moving to the LVT.

So, is the next mayor ready to turn up the heat on housing? The ghost of Henry George is howling, “Just do it!”

—

Notes

[1] Today, mainland China might come closest to what Henry George had envisioned. All municipalities in China own the land in their respective cities and sell land use rights. Thus, there is no private land as George had wanted. However, China’s land use policies are not problem-free. For example, local officials concerned with raising funds for infrastructure have sold land leases to developers to build housing before demand has appeared. This is one of the reasons China suffered a real estate bubble and crash. More broadly, over time, municipalities across the world have experimented with some form of land tax (usually taxing land at a higher rate than structures). The results have been mixed. While most economists support a land tax, it often generates political blowback given the difficulty of transitioning to the new regime. See Land Value Taxation Theory, Evidence, and Practice (2009) by Richard Dye and Richard England, which provides a history and review of land value tax implementation.

[2] One important consequence of the tax system is that a change from a 3-unit residential building to a 4-unit one triggers a dramatic rise in the property tax. Say, you have a 3-family home, your AV is 6% of the market value (based on recent comparable sales). Now, say you subdivide a floor to create four units; instantly, your AV goes up to 45% of market value (based on estimated net operating income). While the tax rate goes down from 20.085% (for Class I) to 12.5% (for Class 2), it creates the situation that for a $1 worth of property, 0.06*0.2085 (=.012051) is much less than 0.125*0.45 (.05625). In effect, NYC applies a severe penalty for those who want to increase their homes from say 2 or 3 units to 4 or 5.

[3] This is almost certainly a significant underestimate of the true market value of the land because the City calculates market values for Class 2, 3, and 4 properties by dividing each building’s net operating income (NOI) by a 12% cap rate. The true cap rates for the city are between 5 and 6%. However, Class I properties make up 60% of all properties in NYC. Little information is given by the City on how they determine the proportion of total market values assigned to the land relative to the improvements.

[4] For now, as we mentioned above, we leave the exemptions as they are, but it is worth asking whether the current set of exemptions is fit for its purpose. What kinds of land does the city not want to tax, and why? We leave this discussion for a future post.

[5] It is something of a historical irony that presently many working-class residents believe “speculators” should “sit” on their land rather than tear down buildings to build more housing, as redevelopment is seen as sparking gentrification and higher housing prices. In the late 19th century, speculators doing nothing with their land was seen as bad for the working class.