Jason M. Barr November 7, 2018

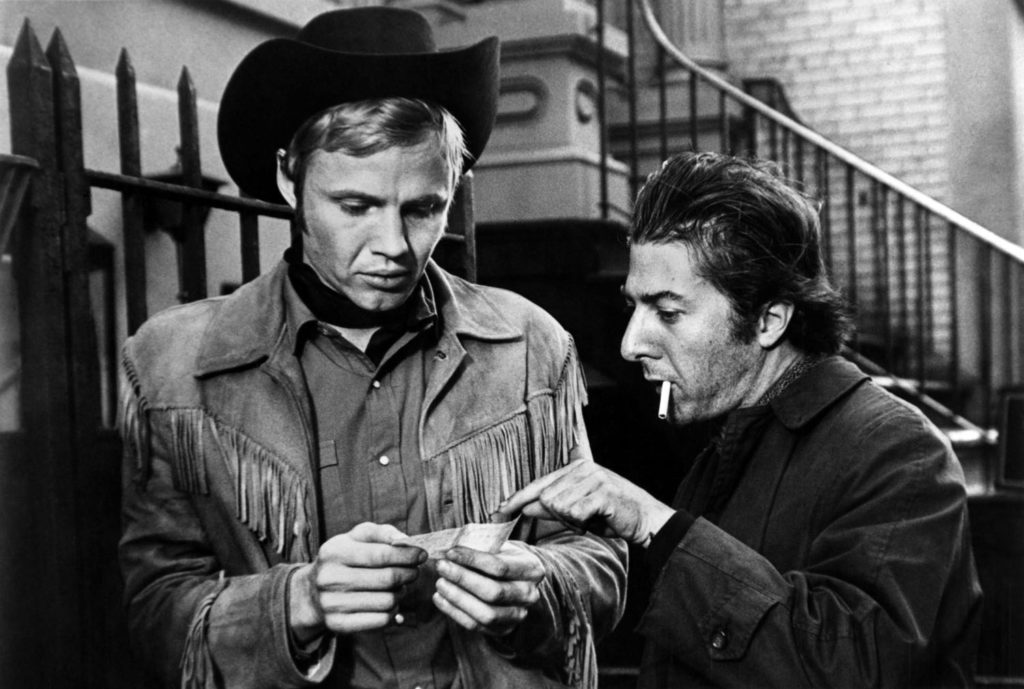

In the 1969 film, Midnight Cowboy, the eager young Texan, Joe Buck (played by John Voight) abandons his hometown and makes his way to the Big Apple. Like countless souls before him, there he seeks his fortune. Buck quickly realizes that easy riches in the metropolis are a pipe dream. He befriends the sickly con artist, “Ratzo” Rizzo (played by Dustin Hoffman), who pimps him out to lonely housewives. In the end, the two, dispirited, head to Miami. The story of Joe Buck and Ratzo Rizzo embody the lore and legend of the big messy city, which either vaults you to great wealth and power, or eats you up and spits out your remains. It’s a tale of urban churning, where youthful ebullience curdles into disappointment on the mean streets.

But that was eons ago. Today, in the 21st century, with crime and unemployment at all-time lows, the perception is that the city is now welcoming to those who want to stay. With clean parks, bike lanes, Starbucks, and Disney, New York is no longer Gotham Noir but a family-friendly metropolis. But is this true? Are people staying once they arrive?

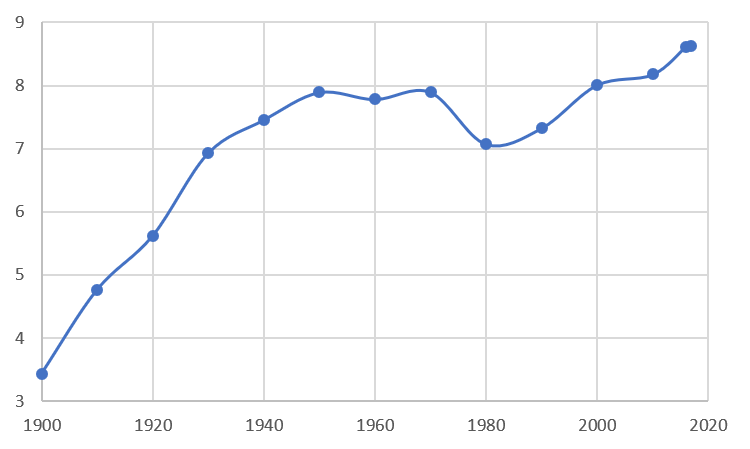

Population Trends Since 1900

In the first part of the 20th century, New York’s population grew very rapidly. At 3.4 million in 1900, it peaked at nearly 7.9 million by 1950. Then in the 1970s, New York lost over 800,000 residents (more people than living in Wyoming and Alaska combined in 1970). The headcount began to rise again in the 1980s; it recovered its “lost” population by 2000. Today the city holds the largest number of people in its history. At its current growth rate, New York is going to hit nine million by 2023.

Comparing the population growth rates from say 1900-1940 to 1980-2017, shows that in the earlier period, the average annual increase was about 1.9% per year; since 1980, the rate has been about 0.5%; and in no decade since 1980 has the rate ever increased at 1%. In short, though the population has been growing, it has never approached the kinds of growth rates considered typical during the first half of the 20th century. In essence, population growth in the 21st century has been relatively slow.

Life and Death in the Big City

A city’s numbers can grow in two ways. First is through natural increase. Each year, thousands of mothers give birth to children, who then become part of the population. Simultaneously, many people pass away each year, causing the count to fall. Over the 20th century, for example, the death rate in New York City has steadily been declining due to rising incomes, improved health care, the changing nature of work, and a cleaner environment. Births rates over the same period have also been falling. Despite this, in every year since 1900, the number of births has surpassed deaths and the city’s population has grown through natural increase.

The second way that the numbers change is through the process of inflows and outflows. The city is a great churning machine—perpetually turning over its population. In-migration can take on many forms: those coming from abroad; from other parts of the country; or from within the region. In parallel, people are constantly leaving: children grow up and go off to college; young families set up shop in the suburbs; retirees move to warmer climes, and so on.

But the question remains: to what extent do the in-movers—native and foreign alike—tend to stay over time, on average? Is the clean, safe, robust city of the 21st century helping to contribute to its growth? The answer appears to be “no.”

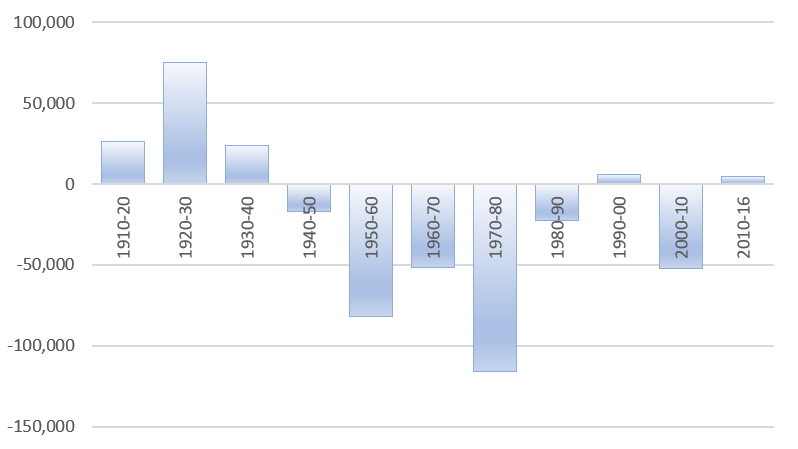

The Decomposition

Using Census data, for each 10-year period since 1910 (and the six-year period from 2010 to 2016) we can decompose the population change into that part that came from natural increase versus that part that came from net migration. For example, if the population over a decade increased by 200,000 people, and, through natural increase, the city added 150,000 new children over deaths, then, the net migration over the decade was 50,000 people (or 5,000 people per year, on average).

The results of this exercise show that the city, essentially, stopped growing from net migration in the 1930s. For every inter-census period since then, out-migration was either greater than or very close to in-migration. Since 2010, Gotham has added, on average, about 5,000 people per year from net migration—statistically close to zero in a city of 8.5 million. From 2000 to the present, this number has been negative.

In other words, the population growth that has characterized New York City in the 21st century is something of an illusion. This increase is coming from residents who have have children, and that the elderly are living longer. But growth overall is being diminished by the thousands of people leaving each year. Why might this be?

The Cost of Housing?

There are clearly many reasons why cities “churn.” People are pulled away to new opportunities; while others are “pushed out” by quality of life issues and the cost of living. Arguably, one of the most important problems facing New Yorkers in the 21st century is housing affordability. The city’s resurgence has caused home prices to rise. As discussed in prior post, in a well-functioning housing market, rising prices should be met with a substantial increase in new housing, which should then moderate these increases, so that costs, relative to income, remains stable. But this hasn’t happened; prices, on average, keep ascending. If you own a home, that’s a good thing (and the reason why homeowners block reforms aimed to increase housing supply). But if you are a renter, it’s a bad thing.

Furthermore, if you are considering moving into the Big Apple you must consider whether you can muster the resources to pay for a place. In East Hampton, Connecticut, for example, for $184 you can buy one square foot of housing. In Winchester, Virginia purchasing that square foot might cost you $249. In Brooklyn, you might have to pay $667; while in Manhattan, it will run you over $1,000, if you are lucky. Many are reluctant to pay those prices.

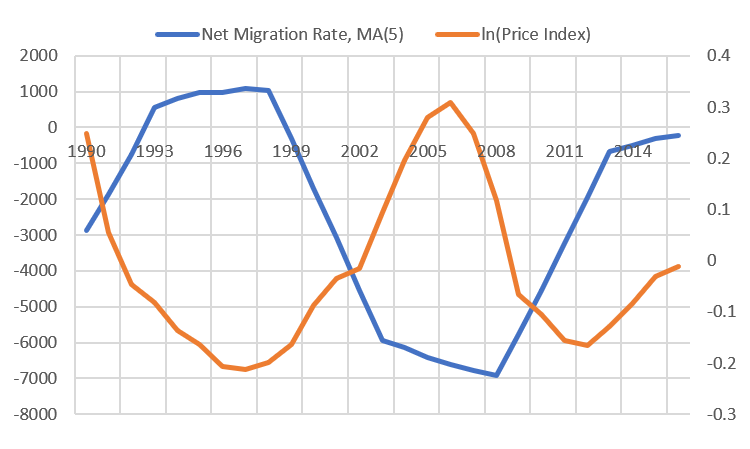

The Data Dive

To what extent is housing affordability acting as a barrier to urban population growth? To answer this question, I created a data set on annual housing prices and net migration from 1974 to 2016 for New York. As a first test, we can look at a graph that compares housing prices with net migration rates (given in the figure below) from 1990 to 2016. We can clearly see that in years with large run ups in (de-trended) housing prices, net migration is negative. That is to say, there is a strong negative correlation between housing price increases and inflows into the city.

The Test

But correlation is not causation. To better isolate the degree to which housing prices are reducing the population, I perform a more detailed (regression) analysis. (The data sources, methods, and results can be found here.) In short, after controlling for other important variables that drive New York City net inflows (such as total foreign immigration and relative unemployment rates), I still find strong evidence that the cost of housing is acting as a deterrent to New York’s population growth. A 10% increase in the cost housing in a given year causes the city’s population to drop by about 4,500 people, on average; which is about the average annual value since 2010.

The Glass Dome

What these results suggest is that the Big Apple is encased in a kind of glass dome. Restrictions on new housing construction means that the city is not as welcoming to newcomers as it was in the past. During late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the Great European migration was in full swing, New York became home to countless strivers who were able to achieve substantial social and economic mobility within their lifetimes, and this helped contribute to American economic success. These immigrants were able to obtain affordable housing because the market was catering to their needs, given their ability to pay.

Today, rising housing prices are impacting the city and its people in two key ways. First, by lowering population growth it also, likely, slows economic growth. Research by Raven Saks Molloy, for example, shows that across the U. S., the more restrictions in a particular housing market, the lower is its employment and job growth, on average. While Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate a large reduction in national growth (GDP) rates because cities like New York and San Francisco limit their housing supply. By placing restrictions on its housings stock, New York–by design–is limiting its economic growth; growth which can be used to pay for desperately-needed improvements in its infrastructure.

Rising home prices also have the impact of contributing to widening income and wealth inequality. One- and two-family homes constitute two-thirds of all properties in New York; and they use about two-thirds of the land currently devoted to housing. Yet homeowners only make up about 1/3 of the residents. New York City’s zoning codes mandate this to be so. In essence, the city has legally given a kind of monopoly power to property owners, at the expense of renters and newcomers. These high rents reduce savings and money that can be used for investments in education and skills, which increases personal income, and enhances economic growth more broadly.

What Kind of City is New York?

And still, in the 21st century, we must continue to ask ourselves: What kind of city is New York? Is it a home for the strivers–a home to the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free“–or is it a glass dome–protecting home values at the expense of the entire city? That we even have to ask this question suggests we forgot the answer.