Jason M. Barr February 20, 2019

Is it possible they built their machines too well…gave them pride and a desire to survive? Machines that wanted order and logic and found that frustrated by the illogical emotional creatures that built them?

–Captain James T. Kirk to the ancient android, Ruk (TOS:S1:E7, What Are Little Girls Made Of?)

A Brief History of the Economic Revolutions of Homo Sapiens

Our world is characterized by rapid technological change. The root cause of this is the need for economic growth. This quest for growth, however, is relatively new in the long history of homo sapiens, who, for scores of millennia, roamed the Earth ingesting its fauna and flora. After the end of the last ice age, some 12,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Revolution, humans learned to domesticate nature’s bounty and settled down. Thanks to bronze (and then iron), they created cities. An economic-political system of imperial agrarianism reigned for about six thousand years.

But gunpowder technology and European rivalries then produced the Commercial Revolution. Running from about 1500 to 1800, this new system saw the rise of nation-states, global trade, innovations in financial products and markets, and a new business form—the corporation; this was combined with the commercial application of scientific discoveries.

From Capitalism to Post-Capitalism

Mercantilism gave way to the Industrial Revolution—the use of mass mechanical production methods to satisfy the needs and wants of homo sapiens. The factory and new sources of energy created the modern capitalist system, where, economic growth was required to sustain itself, since competition demanded a continued return on invested capital. Before then, no one expected, nor required, economic growth. For the most part, imperial agrarianism was a zero-sum game of one empire winning at the expense of another. Growth in total output came mostly from expanding cultivated lands, rather than increasing the productivity of individuals.

Because of continued economic growth and technological change, the Industrial Revolution, at least in the West, pivoted in the late 20th century. It has given way to post-industrial capitalism, marked by the manufacture of intangible goods and services. What economic revolution will come next? Likely some form of post-capitalism, where products are produced instantaneously on demand, and innovations in transportation, communication, and energy may render many forms of trade and labor as obsolete.

The Unintended Future?

There’s no iron-clad law that says that economic evolution must generate improvements in the quality of human life. Economic growth followed by economic collapse, for example, lead to World War II, and untold death and destruction. While it seems we may have learned from past mistakes, there’s no guarantee that we are out of the woods: tribalism, and the hate that it thrives on, is resurgent; tribalists and autocrats are exploiting technologies, like the internet and social media, that were supposed to improve our lives.

Our obsession with technological advance can most certainly generate unintended consequences. Elon Musk, for example, has recently called Artificial Intelligence (AI), “The biggest existential threat to humanity.” The late Stephen Hawking agreed with this sentiment, saying that, “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.”

Yet despite these warnings, the sprint for more powerful cognitive machines—and the economic growth they are intended to engender—is as feverish as ever. Just this past week, President Trump signed an executive order laying out a plan to boost AI technology, “amid growing concern that the U.S. is losing out to China.” The combined forces of business competition; the deeply ingrained nature of computerization in our society;[1] and the perpetual quest for knowledge and technological advancement, bring us closer and closer to a world where machines can think for themselves.

Where are we headed?

Life in the 23rd Century

Arguably, the late 1960s represents, in the U.S. at least, peak industrial capitalism. As computers began to seep deeper into our lives, futurists could begin to envision the possibilities and pitfalls of our collective future. Enter Star Trek. The show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry (1921-1991), and the team of writers, imagined a post-capitalist world, where markets are marginalized, and humans no longer need, or want, to engage in cut-throat competition.

Released from the drudgery of work and the treadmill rat race, people are free to seek knowledge and explore space, the final frontier. With the elimination of poverty, hunger, and want, humans finally achieve utopia on Earth through rational thought, mutual understanding and trust, and a reasonable use technology. But only if they learn from the mistakes of the past and if they are not consumed by the very technology that enables the good life.

Star Trek and AI

The idea that artificial intelligence could destroy our society is not new. At least since the computer was invented, dramatizations about their power began to be appear in movies, television, and novels. But Star Trek is particularly important because each episode offers a thought experiment about what could befall humanity if it is not careful.

During the run of the original series (TOS), from 1966 to 1969, Captain James T. Kirk and his crew on the USS Enterprise, in the 23rd century, traverse the galaxy on a five-year mission of exploration and peace. In their journeys, they encounter situations and societies that present ethical, moral, and physical dilemmas for the crew and humanity more broadly, including several (inherent?) paradoxes created by artificial intelligence.

Back to the Future Matrix

I would argue that, in particular, there are four key fears about computerization that run through series, though they can be reduced to two basic themes: first is that AI and self-aware machines will protect themselves at the expensive of people; and second is that we will become so dependent on intelligent computers that we will become infantilized—the machines will remove from us the very elements that make us human. We will, in short, become the domesticates (if not outright slaves) of the very machines that were produced to help us.

Fear I: Kill to Live

In several episodes, the Enterprise encounters intelligent machines. Once the computer becomes aware of its own existence, its primary mission changes from its original programing to that of self-preservation.

The M-5 Multitronic

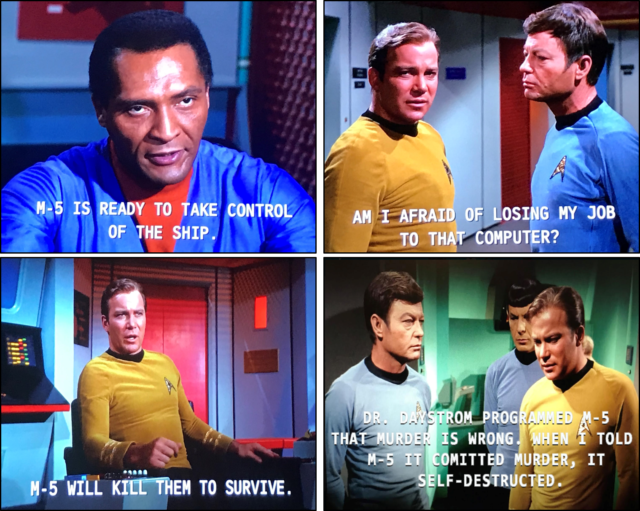

In S2:E24, The Ultimate Computer, computer-science genius, Dr. Richard Daystrom, is given the opportunity to test his new AI machine, the M-5, on the Enterprise. The computer is to take control of the ship and engage in war games with other federation starships. When informed of this new policy, Kirk becomes vexed—it now seems the computer will render his job obsolete.

But once the machine is switched on, it becomes increasingly intelligent and realizes that in order to carry out its mission it must fight for its survival. War games morph into actual battles as the machine fires live weapons at the other ships—killing hundreds of crewmen. The victimized ships are forced to consider destroying the Enterprise in return.

Kirk eventually learns that the machine is programmed with the morality of its programmer, Dr. Daystrom, including the belief that murder is “an offense against the laws of God and man.” Kirk, using his mastery of rhetoric, tells the computer that it is programmed to both murder and not murder at the same time. Unable to resolve the paradox, the computer shuts down and Kirk regains control of the ship.

Fear 2: Infantilization of Humanity

In another set of episodes, humans are not only robbed of their humanity, but have also retrograded and are unable to think for themselves. In each of the shows, in the long past, a computer was programmed to help run the society. But the machine becomes the Great Leader, with the power to enforce laws and norms, and provide for the people’s needs and wants. Over the years, as the species devolve, they retain no awareness that it’s god is a machine.

The Apple

In S2:E5, The Apple, the crew of the Enterprise arrives on a planet that seems a veritable Garden of Eden. They eventually capture a local, who is also the chief priest of their god, Vaal. Each day the villagers must appear before the mouth of Vaal and feed it with fruits and vegetables. This is their life—a simple, but pleasant existence—in good health and ignorant bliss.

But Vaal is also trying to destroy the Enterprise by pulling it down from its orbit. Kirk and Spock learn that Vaal is a computer that controls the society through its priest. Kirk is now faced with a dilemma: save the ship and kill the machine or keep the society intact and let the Enterprise be destroyed.

The episode suggests that life in “Garden of Eden,” is incompatible with the existence of machines. Humans must choose one or the other but can’t have both. In the end, Kirk destroys the machine and destroys their society, offering some overly-optimistic wisdom, “You’ll learn to build for yourselves, think for yourselves, work for yourselves, and what you create it yours. That’s what we call freedom. You’ll like it a lot.”

Fear 3: Perversion of Society

Another idea, intimately related to Fear 2, is that culture and society will be greatly perverted by its fetal attachment to the machine. In other words, the computer causes the norms and rules of society to produce extreme or bizarre behavior among its citizens. Arguably, the distinction between infantilization and perversion of culture is somewhat arbitrary. But in the first case, the episodes illustrate how the computer can make us like children. In the second case, the episodes illustrate how the computer can cause pervasive fear and violence.

Return of the Archons

In S1:E21, The Return of the Archons, the crew arrives on a planet to find that nearly everyone exists in a kind of soulless trance; though during the “Festival” or “Red Hour” they succumb to violent rages against each other. While in their trance, they feel peace and joy—a contentment brought on by the good graces of their god, Landru, who is, once again, pulling the Enterprise down from its orbit. A small band of rebels, unaffected by Landru, lead Kirk to the source of its power—a hidden computer.

In typically Kirkian style, he debates the computer, who claims its objective is the “good the body.” But Kirk insists that the computer is harming the body by keeping the citizens entranced. This, again presents, an unsolvable paradox for the computer, which self-destructs. Turning to one of the priests, Kirk informs him, “Well, Marplon, you’re on your own now.”

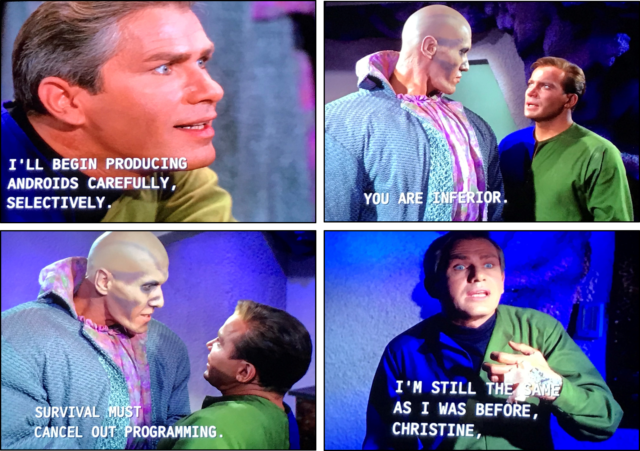

Fear IV: Rise of the Androids

In S1:E7, What Little Girls are Made Of?, the crew finds the lost exobiologist, Dr. Roger Korby, living in underground caverns on the icy planet of Exo-III. He had disappeared some five years before on an investigation of that planet. Upon arriving, Kirk is informed that “Dr. Korby has made some fascinating discoveries.” In particular, he discovers that the ancient dead society had built near-perfect androids. Korby learned that he can replicate people into android form to create immortal humans, who no longer suffer from hunger, disease, or death.

But Kirk’s presence disrupts the plan. An ancient, left-over android, Ruk, remembers why they killed off the old inhabitants. He recalls,

It became necessary to destroy them. You are inconsistent. You cannot be programmed. You are inferior….That was the equation! Existence! Survival must cancel out programming.

We also discover that Korby is not a human but had transferred his self into an android body before dying of hypothermia. In the end, we see that the existence of “perfect beings” is also incompatible with human society. Humans are messy and imperfect. They cannot coexist with those whose sole purpose is perfection and order. Ruk is killed by Korby to protect himself; and then Korby kills himself and the last remaining android when he realizes his dream of the creating the perfect human is impossible.

A Dazzling Display of Logic

The key theme of all these episodes is the apparent incompatibility of human society and self-aware machines. Captain Kirk’s repeated use of logic to disarm the computer illustrates the paradoxes of allowing our machines to have human abilities. Humans will have one agenda and the machines will have another. Disarming machines with logic won’t be so easy. The whole point of AI is that programming adapts and learns from its past experiences to become more efficient at solving problems. In addition, programming that seemingly has an objective objective can take on the biases and subjectivity of its programmers. Self-aware machines can thus easily exploit the tribal tendencies within people that have driven them to repeatedly turn on each other.

While elements of Star Trek seem dated and simplistic, it remains timely because it continues to engage in a dialogue about the possible consequences of being so dependent on upon our computers. Our headlong rush into AI for the sake of economic growth, productivity, and efficiency cannot be taken so lightly.

What’s Next?

Our current retreat into tribalism, and the attempts to deny our collective problems, are slowing down—if not outright stopping—our ability to have real conversations about our future. We are forced to endure manufactured crises while the real one’s fester. If we don’t confront our possible future today, we leave it up to chance and the fate of unintended consequences.[2]

But perhaps we can end on an optimistic, non-dystopian note. By the 24th century, humans have appeared to solve the AI crises of the 23rd century. Aboard the USS Enterprise—captained by Jean-Luc Picard—is the android, Lieutenant Commander Data. His biggest challenge is not how to best destroy humans, but rather how he can become more human. Perhaps Star Trek: The Next Generation can offer lessons on how humanity can peacefully co-exist with its machines. But this is a subject left for a future post.

Note this is Part II of a (hopefully) on-going series on Star Trek and the economics of our future. Part I can be read here.

—

[1] In fact, we are no longer a human society but rather have become a human-computer (humputer? compuman?) society.

[2] As I have argued in a previous post, social scientists can play a role by offering policy suggestions. One way to do this is to model science fiction scenarios using mathematical modeling and computer-based simulations, such as agent-based modeling (ABM). If you are a social scientist interested in using ABM for futurology, send me an email; I would be interested in talking more.