Jason M. Barr and Troy Tassier May 19, 2020

Pandemic 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic rages on with no end in sight. How long it will take to return to normal, at this point, is anybody’s guess. But since the Federal Government has ceded coordination on further mitigation efforts to individual states means there is going to be a hodgepodge of different policies. Each governor has been left to decide on a suite of strategies for its residents.

Some states are on a path to almost full reopening, while others are taking a more cautious approach. This week, most states will loosen at least some restrictions—even New York, the state most heavily hit by the pandemic—will begin allowing construction and curbside retail in portions of the state less impacted by the epidemic. But many areas along the east and west coasts will remain closed for longer.

While opening too soon is risky for those within each state, one could argue that if a state’s residents want to put their health at risk, that’s their choice. But a key problem with this approach is that the virus knows no borders. What happens in Vegas doesn’t stay in Vegas. If you live in a state that remains closed, but the surrounding states are opening—Illinois, for example—you should be worried.

A Brief History of the Coronavirus in the United States

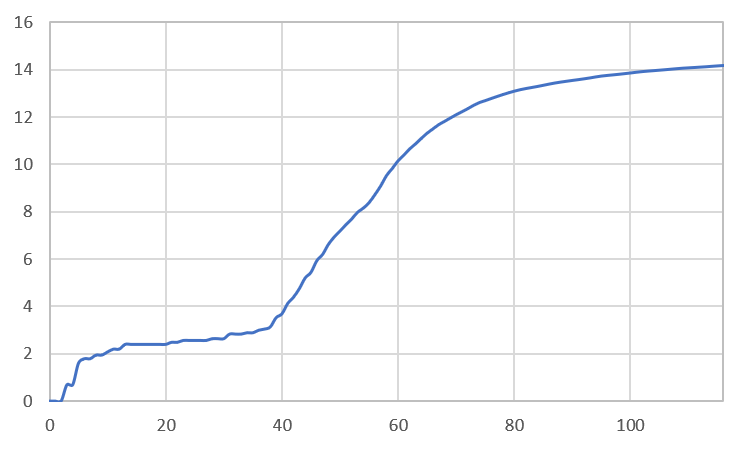

The first case of coronavirus was reported in the United States in Washington State on January 20, 2020. From there, cases started appearing in various places throughout the country. Stage I was “the spark” in late January when the first few cases appeared. Stage II was the initial spread, but only in a few areas that saw infections early on; but it was still relatively contained.

Then around March 1st, everything changed—the virus spread to the rest of the nation. Community transmission (where a source of the infection cannot be identified) became common. About one month later, we see the rate of increase begin to slow, suggesting that state-level social distancing measures had a positive effect. One could argue that if a strong federal policy were imposed before the 40th day since the first infection, the rate of increase would have been much slower.

The Birds and The Bees: The Reproduction Number

To understand the impact of the spread of the virus, we need to review basic epidemiology. It all begins with the reproduction number (R)—the average number of infections one person passes onto the next. For example, if each individual spreads the virus to two people, then the reproduction number is two. In this case, Greg gives it to Marsha and Jan. Marsha gives it to Bobby and Peter. Jan gives it to Cindy and Alice. And so on. Two give it to four, four to eight, and on and on. In other words, with a reproduction number of two, the number of cases double in each generation of infections.

In the U.S., earlier this year, the average reproduction number across all states was a little over two but varied widely across regions. Some estimates place New York City a little under four, while Arkansas and South Dakota may have been below one early in the epidemic. New York was hit so badly in part because of the strength of its social ties.

Four Things

R, however, is determined by four things: the fraction of remaining susceptible people in the population (how many people are left that could be infected), the duration of infection (how long an infected person carries the virus and is able to infect others), the transmission rate (how likely is a susceptible person to be infected if in contact with the virus), and the contact rate (how many other people does an infected person interact with each day when infected).

One fights an epidemic by making R smaller. If it goes below one, then instead of increasing, the epidemic will die out. For instance, if R=1/2, then 100 people become 50 in the next generation, then 25, and so on until the epidemic disappears. Each of the four elements of R can be an avenue for governmental policy.

R-Reducing Policies

We can decrease the fraction of susceptible individuals through a vaccine, but this takes time. We can limit the duration of infection through extensive testing and contact tracing, followed by isolation of the newly infected. The transmission rate can be lowered by prophylactic measures such as wearing gloves, masks and eye wear, and extensive cleaning of surfaces. But the primary method to reduce R has been by lowering the contact rate via social distancing.

After social distancing restrictions were imposed, most states lowered their reproduction number to less than one. Estimates suggest that even New York sits now at about 0.85. But, these values vary across states. Places like Iowa, Illinois, and Arizona are likely sitting just above one. Some like Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Vermont, are well below one. But as states reopen, their R is likely to increase, even with slight easing of social distancing policies. Additionally, there appears to be no systematic effort for wide-scale testing and contact tracing.

Do No Fences Make Bad Neighbors?

One of the things that students learn early in an economics course is that no individual is an island. The buying and selling decisions of the masses determine the price you pay for any common consumer good you care to name. Laws are passed to limit the pollution of automobiles so that we don’t have too large of an effect on the clean air of others as we commute to work. We ban smoking in many public places, so non-smokers don’t breathe second-hand smoke.

These spillover effects are called externalities. Externalities don’t have to be bad. Planting flowers in your yard has a positive benefit to your neighbors across the street. The vaccines that you get to prevent you from falling sick from the flu also prevent you from infecting others; thus, your decision to get a flu shot makes everyone around you safer.

Many states are making decisions to reopen based on the caseloads, hospital capacities, and economic circumstances within their own borders. But they seem to be considering less, if at all, the potential impacts on surrounding states. A virus does not respect state borders. There is no visible or invisible fence that keeps coronavirus from passing from Georgia to Florida, or from Iowa, Wisconsin, and Indiana (each a high profile state that is reopening) to Illinois, which is still struggling to keep its caseload under control.

Regional Pacts

This is the reason that some states have formed regional pacts to coordinate their reopenings and reduce the negative externalities. For example, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts have formed a multi-state agreement to coordinate their COVID-19 responses. It is a form of centralization that will help, especially those states in the center of the region like New York and New Jersey, whose state borders are all within the pact’s boundaries. Pennsylvania, on the other hand, shares a border with Ohio, West Virginia, and Maryland. How that affects the Keystone State depends on how well their neighbors “behave.”

Corona Caseloads

To better understand the basic spread of COVID-19 we have undertaken a range of statistical analyses of county-level coronavirus cases. (The result can be found here.) We use data on confirmed cases from USAFacts.org and estimate what drives its spread by looking at variables within each county. In general, we find that the initial seeds of the epidemic in a local region tended to be driven simply by bad luck and the presence of airports.

But once it arrives in a location there are several things that impact its spread. Specifically, over time, denser counties, and those with more use of public transportation have faster growth rates—even with mandated stay-in-place measures.

Spilling Over

But to better understand the virus’ spread, we looked at how the neighboring counties affected each other. We do this in two different ways. First, we measure the average number of cases on March 20 in all surrounding counties that share a border with each county. We then statistically estimate the impacts of neighboring county cases on the original county, as of May 9th. Second, we measure the number of cases in all counties on March 20 but discount the effect of counties that are farther away. So, this gives an average number of cases in surrounding counties, with more weight given to those closer by.

No matter which measure we choose, we find significant and large externalities across county borders. That is to say, the number of cases in surrounding counties has a significant impact on the number of cases in each county, on average.

Border Effects

We discuss the adjacent neighbors first. Let’s take two counties—call them Oak and Maple, respectively—that are the same in all respects but one. They each have about the same population density, social-economic, and racial profile, etc. The only difference is that Maple County’s neighbors have a 10% higher number of cases, on average, than Oak County. That is, the only difference between the two counties is what’s happening outside of them.

In this case, our data estimations indicate that Maple County will have 2.7% more cases than Oak. In other words, about ¼ of a one-percent increase of the cases of your neighbors are passed on to you within 60 days. If we do this same procedure but include all counties across the country but discount counties that are farther away, we get even larger effects. A 10% increase in the cases of other counties results in a 7% increase in cases in your own county 60 days later. The result from this method is larger because it considers how cases multiply across space. Your neighbors are affected by their neighbors, who are affected by their neighbors, and so on. The impact from the 60-day window illustrates how these effects are long lasting.

Magnitudes

As an example of this magnitude, suppose that in isolation, you would expect to have 1,000 cases based on your profile of population, density, public transportation use, etc. Then suppose that your neighbors (in decreasing weight by distance) have twice as many cases as another similar county’s neighbors 60 days ago. This doubling of your neighbor’s cases would result in you having 1,700 cases instead of 1,000. So, you have an extra 700 cases as a direct result of your neighbors’ influence on the pattern of the epidemic. This is the negative spatial externality associated with this epidemic. It is the reason why states and regional areas are or should be coordinating their efforts.

The main takeaway is that surrounding states can initiate a rise in cases and deaths of their neighbors. If a state, such as Illinois, is struggling to keep its R value under one, and therefore remains closed, but it starts getting “spillover” cases from a neighboring state it could trigger Illinois’ value of R to go above one, thus making it difficult for them to keep their epidemic under control, let alone reopen their economies.

Corona 2.0

And, just as there can be negative externalities in cases from a neighbor reopening, there is a positive benefit from a neighbor remaining closed. If state A opens first, it benefits economically from its actions. But, if its neighbor, B, stays closed, A pays a lower cost in terms of the epidemic because it receives fewer spillover cases. Thus, state A wants to open before state B. But, if state B remains closed while A is open, B will experience the negative externality. It loses economically because it is closed, and receives more spillover cases from A. The epidemic in the closed state will be worse as a result (and may even see its R rise to above one).

State B may then be forced to lengthen its stay-in-place policies—and the economic harm they cause—because of its neighbor’s actions. State A gets to “free ride” on its neighbor for a while. Of course, free riding will backfire. If state B has a spike of cases, it will come back to its neighbor A in the future.

The Summer of our Discontent?

This lack of coordination can have even deeper ramifications for the nation as a whole. By triggering new outbreaks across state borders, it makes the U.S. radioactive. Other countries are likely to join together to allow trade and travel among themselves, leaving the U.S. behind while the suffering and death toll drags on because some states are going it alone.

In the meantime, let’s hope an effective treatment or a vaccine gets here soon…

[…] general response by governors across the country was to close businesses, schools, and other public institutions, and send everyone home to “shelter in place.” While the epidemic in New York is far from over, […]