Jason M. Barr April 30, 2019

[Note that this is the third part of a three-part series on New York City’s first comprehensive land use regulations, enacted in 1916. Part I focuses on the history and thinking of the city’s reformers. Part II reviews this thinking through the lens of modern economic analysis. This post argues that the ideas and rules from 1916 set the stage for today’s NIMBYism and housing affordability problems.]

Zoning looks to the future and is not so much intended to cure past errors as to prevent future invasions by improper buildings and uses. Zoning seeks to protect and stabilize what is good and prevent what is bad. It seeks to make localities more attractive for their proper uses. It is based on the assumption that what is more attractive is more valuable. – Edward M. Bassett, 1931

Everybody Must Get Zoned

Today, America is totally zoned. That is, nearly every municipality in the country has regulations on land use that dictate what kinds of buildings can or cannot be built on every piece of property. These rules specify, often with bewildering minutia, whether a lot must be used only for residential or for commercial; if it must be for single-families or if apartments buildings are allowed. They specify the maximum building height and the minimum building height; how far the structure must be set back from the street; whether the property must contain off-street parking; the maximum square footage; the minimum square footage, and on and on and on. These zoning codes are like the Ten (thousand) Commandants: they tell what you can and cannot do; and implicit in them is that they are good and proper. Residents, government officials, city planners, and developers all have come to accept them as an inherent part of urban (and suburban) life.

The Impacts of Zoning

The impacts of zoning, however, have gone way beyond what was originally intended. The planners and officials, who first established them in big cities across America, sought to regulate the hitherto unregulated land markets to provide some order to real estate development. It was designed to keep factories away from homes; to limit congestion and overcrowding; and to promote open space, light, and air in the residential neighborhoods.

But as zoning took root in the first half of the 20th century, it began to transmogrify. What was meant to place some limits on new development evolved to give inordinate power to owners of already developed properties. Once the maps and rules of each zone were set, the city government had very limited power over what did or did not happen within each zone. Their primary power was, and is, over enforcement, and the right to grant “variances”—permission to slightly bend the rules (if say someone’s new pool is going to be foot closer to the property line than it should be) if no one protests too loudly. From time to time, municipalities consider re-zoning particular neighborhoods, but they are usually ad hoc, and more likely than not, will reduce the allowable density, as a benefit to the existing property owners.

By shifting the power of regulation away from a more centralized mechanism to set rules within each zone, it has promoted the rise of NIMBYism and the power of individual property owners to use the law and regulations to stop development around their lots. Zoning began as a tool for creating order and has ended up as tool for freezing the city.

The Homevoter

The money invested in a home represents, for many Americans, their largest form of savings. Unlike stocks or bonds, most families can’t hold a diverse real estate portfolio. As a result, they start thinking not like a tenant or resident, but like a bank, which seeks to protect the value of its main asset. After 1916, when comprehensive zoning started in earnest, it began to dawn on homeowners that the codes, which proscribed limits on building construction, could be used as means to slow down, or even halt, changes in their neighborhood that might threaten the return on their investments. As an added “bonus,” the rules could help achieve other desiderata, such as keeping out the poor, the homeless, or specific types of businesses, without engaging in direct discrimination.

Resultantly, zoning has become the weapon of choice in the NIMBYist’s arsenal. As documented by economist William Fischel, by voting into office sympathetic officials, homeowners could make sure that the zoning maps became increasingly stringent. Any changes to the maps or individual lot designations must be preceded by hearings and allow the community to voice their anger or fears of harm that these changes will make. Politicians reluctant to displease their constituents, avoid this “third rail” of local politics, and keep the status quo. The bold mayor who seeks to change it has to contend with lawsuits and vocal protests of “Not in My Backyard!”

The Cost of Zoning

The harm of over-zoning America has been clearly documented. By ossifying the real estate market, it contributes to the higher cost of housing in America’s large cities; it reduces employment and economic mobility; it increases income and wealth inequality; and it reduces economic growth more broadly. Though zoning is not the only reason for America’s problems, its ubiquity and entrenched nature is doing more than help. Yet those who benefit by it are—rationally, I might add—addicted to it. As a result, we are stuck in a prisoner’s dilemma like situation—what’s good for the homeowners of the world, is bad for society at large.

A Passive Prophylactic Process

But, because zoning’s impact occurs through a passive prophylactic process, its harm is invisible. We can’t blame what we can’t see. Rather, developers and landlords are the ones who receive the invective because they are the agents of neighborhood change. Developers, by responding to price signals, tear down older buildings and provide taller ones and destroy the charm and character of the neighborhood that was supposed to be frozen by the zoning regulations. Landlords, by responding to price signals, displace low-income and long-term residents and beckon the gentrifying class who then jack up the price of housing and destroy the charm and character of the neighborhood that was supposed to be frozen by the zoning regulations. It’s easy to blame those who appear to be changing what was supposed to be fixed. As a result, residents seek more protections from the city. They ask the mayor to prevent new construction, or to freeze rents to stop gentrification. They react by requesting more ossification and the problem just gets worse and worse.

Revisiting 1916: The Zoning of New York

How did this happen? Where did all begin? Here I want to document the story of the birth of zoning in New York City, which was instrumental on setting us down the path we have today. New York is important for several reasons. First, in 1916, it was the first city to enact comprehensive zoning rules that dictated the use, bulk, and shape or height of every property within its municipal boundaries. This is not to say that New York invented zoning, or was even the first to dabble with it in America, but because of the city’s scale and importance, it clearly occupied an influential leadership position.[1] Additionally, New York’s trajectory from 1916 to the present is emblematic of many cities throughout the country, which have seen increasing stringency of the rules, and a greater transferring of (implicit) power to NIMBYists. Its history embodies the path from the dynamic city to the sclerotic city.

1 BZ: The City Before Zoning

After the Civil War, America’s urbanization began in earnest. Between 1870 and 1920, the U.S. population went from being a quarter urbanized to half. As immigrants and rural folks poured into the cities, developers responded to the demand for building space. They put up low income housing in the ethnic enclaves; they built skyscrapers for the new breed of office workers; and they constructed factories for the products that were in high demand.

Developers, however, acted in an uncoordinated manner. They made decisions about the use, bulk, and height of their properties based on what they believed would generate the highest return. They could, in theory, build a 30-story apartment building in the suburbs if they thought it was good for them (though it would not likely have been profitable). If low income shelter was needed, developers would provide that which was affordable, and, as result, it came with few amenities, such indoor toilets or access to sunlight.

The Messy City

Because of the rapid growth, in the late 19th century, cities began instituting a series of building reforms. They included fire and safety regulations; and laws that low income housing required running water, minimum room sizes, and sufficient light and air. Some cities, like Chicago and Boston, imposed outright height caps. But there was no systematic or comprehensive set of maps that detailed what could or could not built in all areas of the city.

To city officials and reformers, the uncoordinated, overcrowded city was a mess. Low income housing created dens of vice and disease. Factories in the heart of the city drew massive crowds of workers during the day, generating congestion and health and fire hazards. A real estate developer who put up a new skyscraper would instantly place unsuspecting neighbors in the shadows. When prices were high, developers would rush into the market pell-mell, generating speculative gluts that would then lower property values. Also, some forward-thinking developers might attempt to redevelop a block for a different use, rending the surrounding buildings obsolete, and causing a rapid loss of value to them. And so on. The perception was that the uncoordinated city was a bad city, and it needed to be ordered and organized for the greater good.

The Periphery

But concerns abounded not just about the center, but also the periphery. As streetcars and subways expanded outward, they allowed for Americans to embrace suburban living. The real estate footprint of American cities expanded accordingly; often beyond the municipal boundaries of central city itself. As a result, these central cities began annexing surrounding towns and villages to keep its tax base steady and ensure more orderly growth of the region. These towns and villages were contented to be annexed because they could then benefit from the central city’s suite of services and infrastructure investments at a discounted cost (assuming the corruption of the city government wasn’t too odious). These village could tap into the municipal water supply, get protection from police and fire departments, and have their roads and streets paved by the department of public works. In short, the annexation movement at the turn of the 20th century was a deal that both sides were willing to embrace.

Annexation and Land Use

But what annexation meant for the central cities is that they were now in charge of vast estates of “virgin” urban land in the periphery that were, not that long ago, farms and rural villages. The planners and reformers held their collective breadth and urged action before these areas produced the ills they witnessed in the 19th century—the congestion, the diseases, the overcrowding, the extreme poverty, and the rapid succession of neighborhoods with no warning. It might be that in the central core it was too late to do much except regulate future uses, but the vast hinterlands of America’s metropolises could be organized–zoned–into neat little boxes according the planners’ version of the American Dream—each household gets a lot and a house with greenery and clear air isolated from the chaos and hurly-burly of city life.

1916: The Birth of Zoning

As described in Post I of this series, in the 1910s in New York City, the political and economic forces that lead to zoning began to form. Local progressive leaders were increasingly able to have a say in government affairs. The sequence of events in New York began in 1911, when Fifth Avenue retailers petitioned the city for help against encroaching factories. This eventually led to the formation of the Heights of Buildings Commission (HBC), lead by lawyer Edward M. Bassett. The commissioners studied in great detail the nature of the problems, and the attempts to solve them in other places. In 1913, the Commission issued a report. It recommended the zoning of the city, and offered rules on usage, lot coverage, and building height. The HBC essentially had two overriding concerns: stopping overcrowding and its related problems, and preserving real estate values when new buildings went up or when the use of neighborhoods changed.

Zoning is the Future

They couldn’t influence was already built, and so they had to concentrate on the future. The bulk rules limited the ratio of the building footprint to the lot size. The height rules were based on the idea of setbacks—building had to set back after some height, based on the width of the street. The use rules created separate areas for commercial, residential, and industrial structures. In 1916, their recommendation became the zoning law of the land.

The regulations, in practice, were not overly restrictive because Bassett needed to get buy-in from the various stakeholders, and he feared that being too aggressive would lead to law suits that claimed the rules violated the sanctity of private property. In fact, it has been estimated that if built out to full, New York could have held 55 million people.

Variances and Re-zonings

But the zoning founders knew that there had to be some kind of mechanism for individual property holders to seek some dispensation if they could argue hardship. Two processes were established. First individual property owners could seek variances if they could claim good reason and their neighbors did not protest. Second, collectively, a neighborhood could petition the city to rezone particular blocks.

Applying for a variance then gave power to each member of the neighborhood to say no. If they felt the variance was not in their own personal benefit—they could issue a protest as a way to influence the zoning commissioners who were to vote on it. Secondly, the rezoning petitions promoted the possibility that neighbors could work together to reduce the density of their neighborhood further. In essence, they could change the rules in their favor to prevent the neighborhood from changing in away they did not see fit.

And petition they city, they did! Between 1916 and 1959, the zoning codes added some eight pages of single spaced zoning amendments. Some of them were needed because the times were changing and the rules had to reflect new uses and spaces, such as parking lots and gas stations. But the procedure was ad hoc and piecemeal.

From 16 to 61

As the 20th century progressed, the original zoning founders were not happy. They looked around at how things were going, especially during the Roaring Twenties, and they felt the rules were not strict enough. The giant Art Deco Towers, like the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Buildings, were breaking world records despite the attempt to curtail heights. The outer boroughs were growing like weeds and uses remained too mixed for their tastes. Plus, the automobile was coming to dominate intra-city transportation, and the original rules had to little say about how cars were to be incorporated into the land usage regulations.

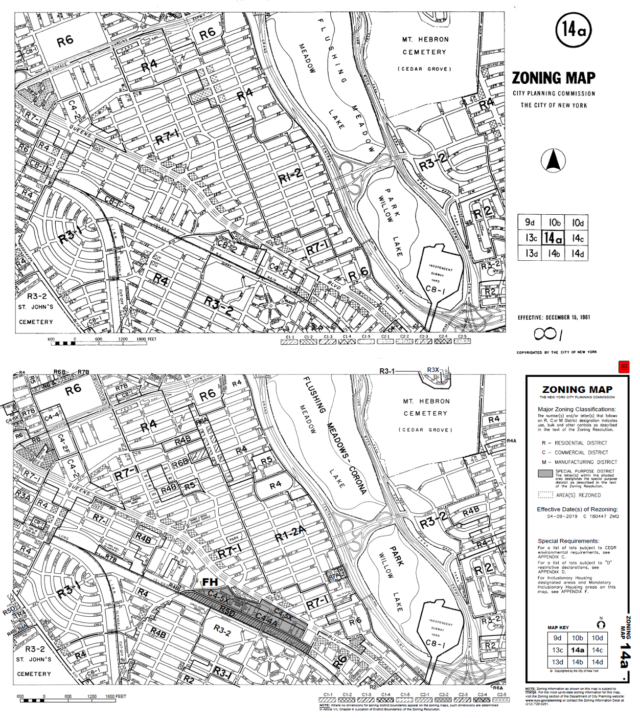

In 1950, a report commissioned by the city, suggested a different approach, and a follow up report in 1958, established new zoning maps, which went into effect on December 15th, 1961. Instead of three simple use categories—commercial, residential, and unrestricted—each was now going to have several, finer-grained subcategories. For example, rather than one simple commercial category, there were now going to be eight, ranging from C1 to C8, where, for example, C1 and C2 where zones for local shopping areas, and C5 and C6 were zones for downtown office development. Neighborhood use and bulk rules were going to be mapped with surgical precision in order to minimize neighborhood change.

FAR Limits

There were no limits to height per se, but the new rules regulated bulk by establishing maximum floor area ratios (FARs), which essentially placed caps on building volume. In Manhattan the FAR in the densest areas were fixed between 10 and 15. For a FAR limit of 10, the developer had to the choice to provide 10 floors on the entire lot, 20 floors on half the lot, or 40 floors on a quarter of the lot. But perhaps, just as importantly, the FAR caps for much of the outer boroughs were set at one or less. This, by law, mandated that large swaths of the city must remain one- or two-family homes. While the 1916 codes incentivized free-standing homes in the suburban areas, the 1961 rules required it to be so. This was a legal, backdoor means of preventing the real estate market from functioning according to the law of supply and demand. The city was now placed under an invisible FAR geodesic dome, with a reduced maximum population of 12 million.

From Yes to No to Yes?

The history of zoning regulations through the twentieth century is like the closing of a vise. The first set of rules were just the foot in the door–they established the idea that property markets would be governed in a particular decentralized way. But planners and officials felt that the original codes did not go far enough. They did not contain the mess, and the grip of the vise had to be made tighter. The residents were happy to go along with this a as it prevented changes around them.[2]

Ironically, the tightening effects on cities were relatively muted until the 21st century. After World War II, urban growth took place either in the suburban fringes of central cities, or in the Sunbelt Cities, where there was still plenty of open land. But the changing nature of work and the rising skills premium has drawn people back to the older big cities. And when they arrive, they find that the place has been effectively squeezed. Whether people realize or not, NIMBYists have used the Zoning Power of No to make the city a game of real estate musical chairs, where the winner has the money to pay for a chair, at the expense of someone else. A century ago, the zoning founders dreamed of an ordered city, a beautiful city, but their legacy is a closed city.

There are ways to move residents from No to Yes, but it requires bold leadership. I have some policy suggestions here. But what can take the place of zoning? I leave that for a future post.

Continue reading Part I here, or Part II here.

—

[1] Los Angeles seems to have been the first city in the U.S. to begin zoning in 1908, but evidently it was not as comprehensive as New York.

[2] It’s hard to see it now, but there were other paths that could have been taken that would have reduced NIMBYism, but I will leave that discussion for a future post.

[…] city’s reformers. Part II reviews this thinking through the lens of modern economic analysis. Part III argues that the ideas and rules from 1916 helped to set the stage for today’s NIMBYism and […]