Jason M. Barr and Gabriel Ahlfeldt August 17, 2020

The Bricks of Ego

When most people look up at supertall skyscrapers, like the Burj Khalifa or the Shanghai Tower, they assume they have been constructed for irrational purposes. The most common belief is that they are built by ego-driven developers seeking to build monuments to themselves.

This certainly seemed like the case in 1931, when the two developers of the Empire State Building, former New York governor and 1928 Democratic presidential candidate, Al Smith, and retired General Motors executive, John J. Raskob, built the world’s tallest building. Raskob was motivated, in part, by a rivalry. He “wanted a building that would literally and figuratively put Walter Chrysler’s building in the shade.” If there was ever a structure built with the bricks of ego, it was the Empire State Building.

And in May of 1931, when the building officially opened, New York real estate was in free fall. As the city entered the Great Depression, people scoffed at Smith and Raskob’s folly by calling their beast, “The Empty State Building.” The vacant offices and negligible cash flow only confirmed what everybody already knew—supertall buildings don’t pay.

But this historical perception begs two questions. First, from the point of view of August 1929, when the developers were establishing their plans, were their decisions really so foolhardy? And second, what has been the long run economics of the building? Nine decades later, the Empire State Building remains a beloved icon. It is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world, and the skyscraper is part of New York’s identity and heritage. How can we resolve the historical accounts of it being a lemon with our current perceptions of it as lemonade?

From Astor to Empire

Before the Empire State Building existed, the site, at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, housed the world-famous Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, which, since 1893, was receiving wealthy guests and holding lavish parties for the scions of the Gilded Age. In December 1928, Bethlehem Engineering Corporation purchased the lot, when the Waldorf-Astoria owners decided to construct a new 47-story hotel on Park Avenue and 49th Street.

However, Bethlehem Engineering had trouble securing full financing for a new building; they then sold the lot to an investment syndicate, led by the Chatham-Phenix National Bank and Trust Company. Al Smith was familiar with the deal and pitched the idea of bringing in Raskob, also his former presidential campaign manager, to buy the lot and build a skyscraper.

Interestingly, the original plans for the site produced by Bethlehem Engineering was a 50-story structure that contained offices and loft space, which was more in line with the neighborhood’s character. Situated close to Penn Station, the district was home to hundreds of designers, manufacturers, and sellers of clothing for the local and national markets.

In August of 1929, Smith publicly announced the plans for the Empire State Building, with a crisp height of 1,000 feet (305 meters). The hope was that the skyscraper would help spur redevelopment of the neighborhood from a dingy industrial quarter to a shiny new corporate sector. After Walter Chrysler topped out his building in October of 1929, Raskob and Smith thought up the idea of adding a mooring mast to allow for the docking of dirigibles; this extruded the building’s height to 1,250 feet (381 m), 200 feet (61 m) higher than Chrysler’s building. No airship captain ever dared the landing.

The 1929 Analysis

History has scoffed at Smith and Raskob for placing some two million square feet (185,806 m2) of office space on the market when the city’s economy was crashing. But from their point of view, in the summer and fall of 1929, when they were at the drawing board, what did the economic landscape look like then? Was their thought process really so irrational?

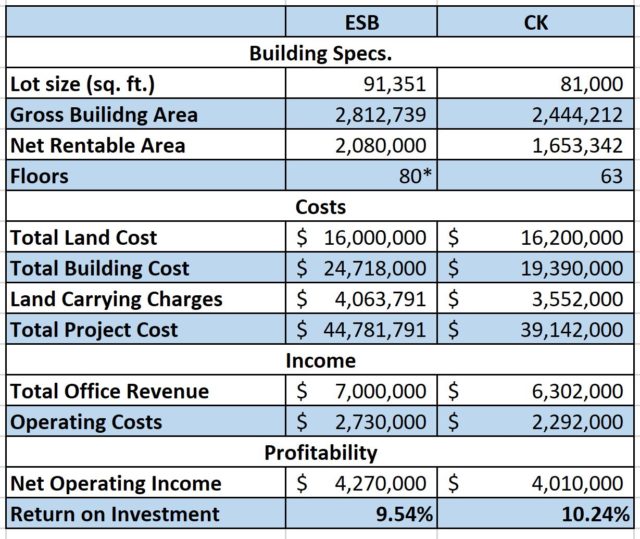

To answer this question, we need a benchmark. For this, we turn to the findings of authors W. C. Clark and J.L. Kingston (CK). In 1930, they published their book, The Skyscraper: A Study of its Economic Height. They play the role of a hypothetical developer of an office skyscraper in Manhattan, on a large lot directly across from Grand Central Terminal on 42nd Street. In fine-grained detail, they itemize the various costs and revenues from erecting a building with varying heights, to identify the one that maximizes the return on the investment.

Based on their calculations, they found that the profit-maximizing height was 63 stories, with a 75-story one a close second. When we start comparing the costs and revenues from their hypothetical 63-story project to the Empire State Building, the differences between the two seem relatively minor. From the point of view of August 1929, the Empire State Building had a strong economic rationale, even if its height was not profit-maximizing. While the building became higher over the ensuing months, the total amount of office space stayed about the same.

Apples to Apples

Let’s turn to this comparison (for data analysis, sources, and notes see here). First is the size of the lot. To make the economics of a tall building work, a large lot is needed. In the CK case, their lot was 81,200 square feet (7,543 m2). The ESB lot is 91,351 square feet (8,487 m2), some 13% larger. Second, the cost of each lot was similar. CK estimated $200 per square foot for the land, while ESB the lot was bought for $175 per square foot.

The ESB has a gross building area of 2.8 million square feet (260,129 m2), whereas the CK building was to have 2.4 million square feet (222,967 m2)—each with a similar floor area to lot ratio. That gave a construction cost, on a square foot basis, for CK of $8.79 ($91/m2) versus the ESB of $7.93 ($85/m2). Turning to revenues, again Smith and Raskob were not unreasonable in their estimates, which they assumed would average $3.37 per square foot of office space ($36/m2), and was comparable to CK’s estimate of $3.81 per square foot ($41/m2). The difference seems justifiable given that the CK building was directly across from Grand Central Station.

When one does all the apples-to-apples comparisons, the best CK building had a return of 10.25%; their 75-story structure had a return of 10.06%. The estimated return from the Empire State Building comes in at 9.54%, which would offer the typical investor a more-than-satisfactory return. Also, keep in mind, these calculations were made without the observation deck, which, when included, would most assuredly have made the ESB a better investment than the CK structure.

The Market Value of the Empire State Building

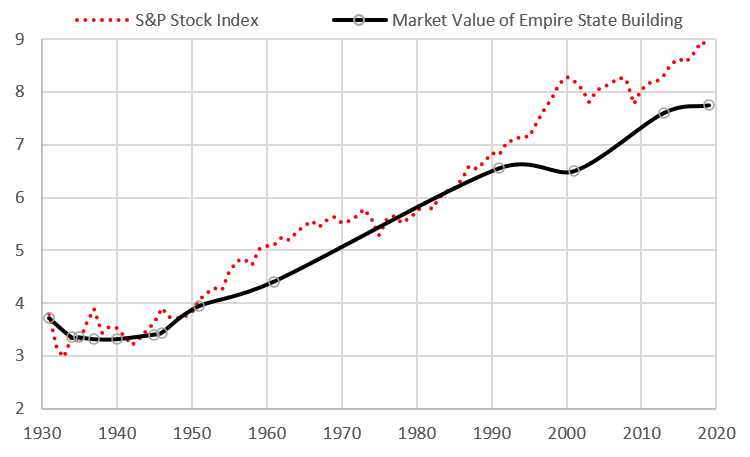

What seemed reasonable at the time, of course, quickly became unreasonable, and was seen by the wider public as an example of irrational decision making. Smith and Raskob faced no shortage of troubles keeping their building during the Great Depression. With help from their wealthy backers, they persevered and made the best of a bad and stressful situation. But here we are nine decades later. What have been the long-run returns? Has it turned out to be profitable, and, if so, how does it compare to other investments from 1931 to the present day?

There are several ways to try to answer this question. For the sake of brevity, we are going to focus only on one approach–tracking the building’s sale price or market value over time, relative to the initial cost of construction. This is like looking at the returns to buying a home—we pay an initial price, and then down the road, we hope to sell it for a higher price. Market values reflect the underlying economic value, which, in this case, is the flow of profits from the skyscraper. Thus, we look only at the capital gains of the building over time, ignoring any profit payouts to the investors. This is also similar to tracking the value of the stock market, without worrying about dividends.

1951

Al Smith died in 1944, and his stake was taken over by Raskob, who continued to run the building until his death in 1950. His estate then sold it to a syndicate, which paid $51 million. The New York Times reported that the sale “was said to be the highest price ever paid for an office building.” And offered up that, “The structure…is now reported to be one of the most profitable single building operations in the world.” Also, about the same time, a 222-foot TV-radio tower was placed atop of the mast and was expected to bring in an additional $1 million in revenue per year. Not bad for the Empty State Building.

1961

Beginning in 1961, things got very, very complicated, with several different organizations having a piece of the ownership action (including through very long-term leases and subleases). In that year, for example, only the building, but not the land, was sold for $65 million. The land had been purchased by Prudential Insurance for $17 million back in 1951 (this was similar to the 1929 land price of $16 million). So, if we assume the building alone in 1951 was worth $34 million ($51 million – $17 million), then the net gain was from $34 million to $65 million, a near doubling in value in only a decade.

The 1990s

In 1991, Prudential was seeking to sell its share. This prompted the New York Times to get estimates of the true market value. It reported, “If it could be sold outright, unencumbered by the leases, the building would have a value of $600 million to $800 million in today’s real estate market”—a hearty gain over the previous three decades.

In 1994, Donald Trump, working with Japanese investors who bought Prudential’s stake, aimed to wrest full control away from the other owners. This was only possible, however, by suing them. In the end—not surprisingly—he failed. The foreign investors, who put their faith in Trump, lost on the gamble, while Trump walked away with substantial brokerage fees.

In the 21st Century

In 2002, after nearly seven years of suits and counter-suits, complete ownership fell into the hands of Peter L. Malkin and his partners. Malkin, along with real estate mogul Harry Helmsley, had been involved with the building since 1961. In 2013, Malkin took his real estate holdings public by forming a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT). At the time, the Empire State Building was worth around $2 billion. And, in 2019, the ESB had a market value of $2.3 billion. In short, over the very long run, the average annual growth rate for the market value of the Empire State Building has been about 5.3%.

It’s also worth noting that, on average, the value of the ESB and the stock market tracked each other for many years. After 1985, the two began to separate, with the stock market going on to greater heights; perhaps this says more about corporate stock prices than New York real estate.

Visions of Grandeur or Grander Visions?

The conclusion here is that, in the long run, the final ego-based version of the Empire State Building was likely more profitable than the more mundane office building originally envisioned by Smith and Raskob. The 1,250-foot tower, with its mooring mast, has provided a greater aesthetic elegance and allows for its famous light displays. Adding the observation deck has been a boon to both the building owners and the world (in 2017, the observatory had 3.9 million visitors who paid a total of $124 million for tickets). Its height also made it ideal for a large TV and radio antenna, which is profitable to both the building owners and society.

Though Smith and Raskob’s projections for office income might have been too rosy for the times, they were certainly not irrational, given that they assumed higher-end corporate clients would use the building. The Great Depression was a financial tsunami that no one could have foreseen and should not be used to judge the structure’s economic merits.

Ultimately, the real enemy of the Empire State Building was not the depression, but rather the slow, inevitable forces of economic change. After World War II, corporate America had a strong preference for larger floor plans and greater light exposures. The Empire State Building was arguably one of the last great old-style office buildings with smaller floor plans and narrower windows. Additionally, the building remained too far south from the heart of midtown. After the war, the new office skyscrapers were built further north of Grand Central Station. Today the Empire State Building remains a lonely giant in the historical retail and garment center.

Nonetheless, while Smith and Raskob struggled to make their building pay in the early years, it’s safe to say that what seemed, at the time, to be visions of grandeur, was, in the end, a grander vision.

More blog posts on the Roaring Twenties and New York City real estate can be read here.