Jason M. Barr April 3, 2023

“More Rundown Buildings Now!”

That should be the new motto for expensive cities. In the current debates on affordable housing, there is no discussion that the best way to help those with the lowest incomes is by letting some of the housing stock decay to a lower quality. The process of new housing for upper and middle-class households eventually becoming low-income housing is called filtering. For many decades, filtering was the primary route to affordability.

Current policies, such as mandatory inclusionary housing and tax breaks for new low-income units, don’t work because they require massive resources to help only a handful of families. The fact that cities hold lotteries for the precious newly built units is prima facie evidence of the absurdity of using new housing to solve the affordability problem. Rationing gems to the lucky few illustrates that the housing market is failing everyone else who must duke it out for what remains.

Decay Can be a Force for Good

The idea that we would let some of the housing stock decay to provide affordable homes was abandoned decades ago. Filtering was, after all, associated with slums, and slums had to be cleared. But to make housing more affordable for everyone, we must think of housing not as an infinitely lived product but as one with a life cycle requiring planned obsolescence. Cities need to expect and create the conditions to allow their housing stocks to cycle over, say, 50-year periods—to let new housing wear down and worn-out housing be replaced.[i]

Thus, filling in the “missing middle” in the housing market is doubly essential. It will not only provide new units for the middle class but will also generate a pipeline of properties that will filter down to the rest.

As I will discuss below, filtering is still vital for millions of residents across America. It’s just not allowed in the places where it’s needed most—in big, booming cities like New York. It’s time to make filtering cool again.

The History of Filtering: Manhattan 1900

In 1900, Manhattan’s immigrant neighborhoods were arguably the densest places on Planet Earth. Block after block was filled with tenements, each chockablock with residents living in tiny, dark units.

Jacob Riis’ 1890 photo essay in his classic book, How the Other Have Lives, advertised the seedier side of tenement life and helped shape public opinion that the slums had to be cleared. He was one of a group of reformers who were convinced they could save the city by surgically removing worn-down, low-income housing. Their goal was to scatter the population into new suburban homes and transform the metropolis into a worker’s paradise.

Yet, despite the overcrowding and the constant influx of immigrants, the truth was that the market was providing affordable housing. One 1907 study of 200 households living in the tenements found that the average family with six people paid 20% of their family income on rent. Only the poorest of the poor paid more than 30%; even in the worst case, it was never more than 43%.

This contrasts with New York City today, where 54% of households are rent burdened in that they pay more than 30% of their income toward rent, and 28% are severely rent burdened in that they pay more than 50% of their income on rent.

The housing was not pretty, to be sure, but it was available and relatively cheap. And just as importantly, the small apartments were considered temporary. The expectation was that families would rent up or move out as their incomes rose. As one investigator of immigrant neighborhoods opined in 1901,

Many tenements in Jewish quarters are owned by persons who formerly lived in crowded corners of others just like them; and from this population comes many and many a Broadway merchant and professional men in plenty. It is a common saying that from Hester street to Lexington avenue is a journey of about 10 years for any given family.

This was only possible if housing was cheap all around.

Supply in the Slums

Several things made sure that affordable housing was available. First was the continual process of generating new supply. And second, was that the buildings were disposable. They were constructed, allowed to depreciate, and, at some point, torn down and replaced with new housing.

To reformers, this idea was anathema, as they were laser-focused on housing quality and the problems of disease and vice. After an investigation of the tenements in 1903, one reformer, Elgin R. L. Gould, blamed the landlords for not taking care of their properties:

The building being flimsily built and the class of people living in it being somewhat destructive, when subject only to the poor management which ordinarily prevails, the item of repairs at the end of the year is large. Removals are frequent, as a slight inducement offered by a rival owner will cause a tenant to pack up and go, particularly to a new building just completed.

But the landlords were just supplying what the immigrants could afford. The constant churning meant that the housing market could fluidly adjust to cater to the evolving needs of the immigrants who poured into the neighborhoods.

Lodgers

Many households took in lodgers. One study of New York working-class families in 1909 showed that 34% of households took them in. Ironically, those most likely to have lodgers had relatively higher wages, as it seems the higher income was used to rent a place slightly larger than needed to let out the rest for a profit.

This provided more income for them and offered the smallest and cheapest housing possible for those who had just arrived from the Old Country. Lodgers represent the ultimate matching of supply and demand with those who were just getting started in America.

The Tenement Lifecycle

Tenement housing was expected to depreciate. There was no way to stop it since, as Gould documented, the residents had low incomes and moved relatively frequently, generating significant wear and tear on the structures. As such, it was typical for an entrepreneurial immigrant to buy an old apartment building, tear it down and build a new one. Relatively well-off residents would move in and pay the higher rent needed to cover the construction costs.

Over the following decade, the building would slowly depreciate, and the rental income would fall. But by then, the mortgage was paid off, and the payback period for the initial investment was returned. From there on, the property was “milked.” As long as the rental income—however low it might be—was greater than the operating costs and the opportunity cost of holding the land with that building, the owner could provide poor-quality but cheap housing.

At some point, the milking process had to end. When the building was in such bad shape, it would be torn down, and the process would start over. And in this way, the Lower East Side tenements had various housing qualities to satisfy the range of demands.

And just as importantly, even during the period of the greatest immigration, when new households were absorbing thousands of units, the market still was affordable because it was flexible. Not pretty, but flexible. And it shows that even in markets with tremendous demand, a city can build to accommodate everyone if it builds rapidly and expansively.

Reformers and Filtering

In the early 20th century, housing reform began to remove filtering as a useful housing option in big cities. Filtering never disappeared, but it slowed down so much that when cities like New York began to rebound in the 1990s, there was very little low-income housing left. What remains is “rationed” through rent controls.

A lot of good came from reform, of course. Laws mandating minimum sunlight, toilets, and hot running water in every apartment were not only done for humane reasons but also to improve community health. But stringent zoning and building regulations, along with slum clearance programs, were designed to prioritize quality over quantity—laudable goals, but not without unintended consequences.

The lasting implications of these policies were that they created limits on new housing construction, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, and they limited the flexibility of building owners to subdivide or adjust their properties based on the needs for different kinds of housing. The result has been to remove affordable housing from the total stock.

Filtering in the 21st Century

In recent years, a handful of economists using cutting-edge statistical methods provide clear evidence that filtering not only still exists but also works to provide low-income housing when allowed to do so.

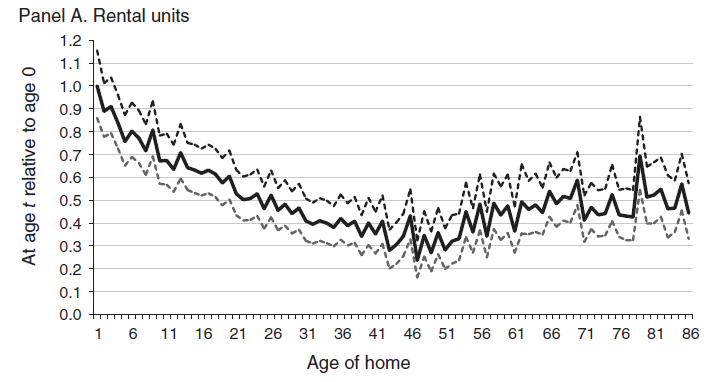

Since it is nearly impossible to get data on the specific nature of housing quality over time, an important 2014 study by the economist Stuart Rosenthal looked at the (inflation-adjusted) income of people who buy or rent housing over time within a sample of the same units. His data set contains over 72,000 housing units in a nationally representative sample between 1985 and 2011, and he then obtains the income of those who moved into these units over time.

His data show that, across America, the average change in moving-in household income is -11.8% for rental units and -7.5% for owner-occupied units. That is, on average, those who moved into these same units had lower income each subsequent round in large part because the housing was becoming older and more worn down.

And using more sophisticated statistical (regression) methods, he finds that filtering is most rapid in the first 50 years of a home’s life. After that, the filtering process typically stops and then reverses itself as homes become prized for their historical appearances or demonstrate that je ne sais quoi that makes them worth preserving or upgrading.

Furthermore, he finds that annual filtering rates are much faster for rental versus owner-occupied units—about roughly -2.5% per year versus 0.5%, respectively. He concludes that across the U.S., on average, “[t]he real income of a newly arrived occupant at a 50-year-old rental unit would be just 30 percent of arriving occupant income in a newly built home….”

Filtering 2.0

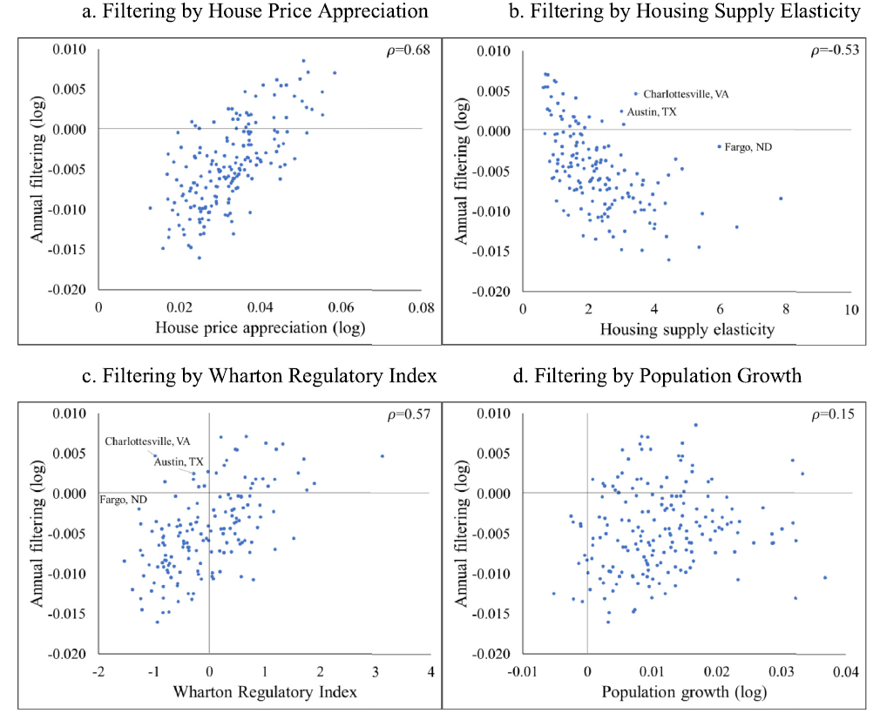

In a paper published in 2022, three economists studied the issue of filtering in the same vein as Rosenthal. However, their data set was much larger—some 1.23 million household “turnovers” in their sample of 1.1 million housing units. They look only at owner-occupied units, but the findings are clear. On average, the rate of filtering for the U.S. housing stock is about -0.42% per year, similar to Rosenthal’s finding.

Within Cities

Because the authors obtained such a large sample, they estimate filtering rates across metropolitan areas and within cities. They find that filtering rates vary widely. Some neighborhoods see rapid filtering rates, whereas others see an upgrading of their housing stocks (call it reverse filtering). In fact, they find that the variation in filtering rates is greater within cities than across them.

Though they do not do a deep dive into what drives this variation, one key finding is that central city neighborhoods have seen significant reverse filtering. This makes sense. As the desire to be in central cities has risen, it has driven up land values and housing prices. Thus, only those with relatively higher incomes can afford to move in. More broadly, filtering is virtually impossible in neighborhoods where housing prices are rapidly increasing.

Across Cities

But just as interestingly, they explore the reasons why metropolitan areas across the country have very different average filtering rates. The main finding is that the ability of a city’s housing stock to keep up with demand—its so-called supply elasticity—is a vital determinant of its filtering rate.

One of the most important factors is the restrictiveness of zoning and the stringency of building regulations. Places with higher stringency have higher prices and less filtering. Thus, in metropolises like New York, San Francisco, and Seattle, where there is relatively little new construction, filtering is greatly diminished and reverses itself, on average.

Moving Chains

To get more evidence on filtering, we can turn to two recent studies that look at so-called moving chains. The idea is to follow the people, not the houses. When a new high-rise apartment building is opened, it initiates a moving chain, where a large fraction of units is occupied by locals who move from other parts of the city. When this happens, the “abandoned” housing is freed up and occupied by someone else, who then frees up their housing for someone else, and so on.

Two new studies statistically document these moving chains and look at the income levels of the people who occupy each vacant unit in the chain. They find that when a new high-price, centrally-located building is created, people of lower income are able to benefit from the empty units in the chain.

Helsinki

One study focuses on the Helsinki metropolitan area (HMA) with about 1.2 million residents. They begin by looking at 106 newly construed multi-family buildings, with 3,196 new units, built between 2010 and 2019 within a 3-kilometer (1.8-mile) radius of the Helsinki Central Station.

As expected, residents in the upper-income brackets tend to occupy these new units. However, they find that

the moving chains triggered by these new units reach middle- and low-income neighborhoods. By round three, 60% of movers originate from neighborhoods in the bottom half of the neighborhood income distribution….By round four, 50% of movers are ranked in the bottom half of the national level household income distribution.

In plain English, the new high-priced units allowed filtering for lower-income people.

The U.S.

Well, maybe, you say, there is something special about Helsinki. Another recent study looks at the moving chains across the U.S. In this case, the economist Evan Mast followed the “hopping” created by the opening of one of 686 market-rate multi-family constructed between 2009 and 2017 in the center of 12 large U.S. cities.[ii]

He finds that 67% of the new units in the central city are occupied by people already living in the metropolitan area. Even in global cities, the proportion is high. In New York, for example, 76% of new-building occupants are from within the New York metro area, and 68% are from within the city itself.

Following people along the moving chains, Mast finds that,

Constructing a new market-rate building that houses 100 people ultimately leads 45 to 70 people to move out of below-median income neighborhoods, with most of the effect occurring within three years. These results suggest that the migration ripple effects of new housing will affect a wide spectrum of neighborhoods and loosen the low-income housing market.

Again, in plain English: New upper-class housing in central cities benefits those in low-income neighborhoods through the filtering process.

We can’t see it amidst the fog of our everyday urban experiences, but if you telescope on filtering, it’s there. It’s just not happening fast enough to keep up with the demand for new housing.

Policy Implications

Research and history suggest that we need to think about housing and cities not as static entities but as dynamic systems. Newly constructed middle-income housing not only benefits those in the middle class but is also the primary means by which low-income housing gets produced. As the research on moving chains shows, we should not fear high-rise luxury construction in gentrifying neighborhoods, though we cannot rely on it either.

Middle-class housing—and lots of it—needs to be built where land values make it affordable to construct, primarily outside the central areas in urban residential and suburban neighborhoods and ideally along key transportation routes and mass transit lines.

The key is to establish a housing market that can quickly and flexibly adapt based on demand conditions. To this end, here’s what cities and states can do.

Flexible Housing

- Allow—even encourage—the construction of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and the subdivision of larger homes into two- or three-family houses. These extra units can generate additional income for the property owner and provide a small and cheap unit for people who need it.

- Reform zoning to allow and promote the construction of mid-rise apartment buildings around transportation hubs and along transportation lines, particularly in the suburbs. Cities need to relax their overly stringent zoning regulations massively. Full stop.

- Allow for office buildings to contain mixed uses. All those half-empty office buildings should be allowed to have several different uses. Keep the offices on the lowest floors and maybe even at the very top ones too. Allow for shopping, schools, and retail in the middle, and permit housing everywhere else. If landlords can earn money by allocating floors to different uses, they should be allowed to do so.

- Encourage the construction of rental units rather than owner-occupied ones since middle-class rentals are more likely to filter down to low-income housing. Ways to do this include providing more generous subsidies to developers of middle-income rental housing and establishing tax-free renter savings accounts for tenants, where an extra part of their rent payment is set aside each month in a savings account (and can be used to pay rents in a time of emergency).

- Move to a land value tax program that taxes the land values at a greater rate than the building value. This taxing scheme will incentivize property owners to densify their land, providing more housing.

Flexible Cities

But as the fierce debates between the Nimbyists and Yimbyists show, change does not come easily. Making the housing market more flexible requires people to be confident that changes will improve their lives. To this end, governments need to create policies that enhance trust and mitigate fear.

As I have discussed elsewhere, two key elements include creating a new type of master plan and a land value insurance program. The master plan would, among other things, provide a blueprint for how new schools, parks, and local services get produced as population density rises. The point is that cities need to get ahead of the services curve to show that quality of life can improve even as neighborhoods densify.

Additionally, cities need to allow property owners to buy land-value insurance, protecting them against possible, though unlikely, drops in their land value because of neighborhood changes. Since homeowners fear drops in their house values, they prevent more housing in their neighborhoods. If they had insurance, they would be more likely to go along with rezonings, densification, and allowing the filtering process to work.

Affordable Cities

If history is any guide, big cities like New York need not suffer from affordability problems. But fear of change and stringent regulations have gummed up the works. Leaders need to do a better job in demonstrating that the lack of affordable housing is harming everyone, not just those in the missing bottom.

New policies cannot focus only on housing but must also address the fear of change and the additional services that will be needed as neighborhoods densify. After all, cities are not just places with houses, but are places where people live.

While filtering has gained a bad reputation because of the historical problems of overcrowding, it has traditionally been the primary source of low-income housing. We need to re-learn this if we truly want our cities to be more affordable.

Works Cited

Bratu, C., Harjunen, O., & Saarimaa, T. (2023). “JUE insight: City-wide effects of new housing supply: Evidence from moving chains.” Journal of Urban Economics, 103528.

Liu, L., McManus, D., & Yannopoulos, E. (2022). “Geographic and temporal variation in housing filtering rates.” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 93, 103758.

Mast, E. (2021). “JUE Insight: The effect of new market-rate housing construction on the low-income housing market.” Journal of Urban Economics, 103383.

Rosenthal, S. S. (2014). “Are private markets and filtering a viable source of low-income housing? Estimates from a ‘repeat income’ model.” American Economic Review, 104(2), 687-706.

——

[i] There are carbon implications to this. On the one hand, as old housing is destroyed or completely refurbished, it can be upgraded to the latest standards that minimize energy usage. Also, except for very tall buildings, mass timber structures can be used to minimize embodied carbon. For that matter, densification is good for reducing carbon footprints.

[ii] These cities are New York City, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Washington, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Boston, San Francisco/Oakland, Denver, Seattle, and Minneapolis.