Jason M. Barr September 3, 2019

Astor’s Vision

On his deathbed in 1848, John Jacob Astor—America’s first millionaire—reportedly quipped, “Could I begin life again, knowing what I now know, and had money to invest, I would buy every foot of land on the Island of Manhattan.”

Astor came to America from Germany in 1783 with nothing but a few flutes to sell. He soon dived into the fur trade and other merchant ventures. With his profits, he turned, in the second half of his life, to investing in land. Astor is remembered an incredible visionary, since he was able to foresee the rise of Manhattan as a global metropolis. To be sure, Astor was perceptive in realizing that Manhattan real estate had tremendous potential, but certainly in the decades after the birth of the American Republic, New York showed all the right signs.

Vacant Land: A New Hope

Astor’s strategy was to buy farmland north of the developed area of the city. As the population grew, rural land was converted to urban uses. First it was carved up into blocks according to the Grid Plan and then each block was subdivided into lots and then structures were built. As the process unfolded, Astor was able to collect higher and higher ground rents. One can say that the real wisdom of Astor’s plan was to buy early and buy in bulk.

His strategy suggests an important difference between lots with buildings and those without them. The value of a vacant (or nearly vacant) lot depends on its potential, as it is, literally and figuratively, a blank slate. In other words, the price of a vacant lot measures the buyer’s belief that someday it can realize its full development potential, or in real estate terminology, its highest and best use. In the central city, a tall tower might most profitable; whereas further away, a low-rise building might be better. In short, a vacant lot represents hopes and expectations. If bidders believe future rents or sales prices will reward them handsomely, they bid up the price. If they feel that the future is somewhat bearish, they might offer less.

Real Estate

Contrast this with a landlord who owns a building. The landlord can be you if you own your home, or she can be a stranger. Either way, the value of the structure is the income or benefit it provides, more or less, in the present. An apartment building, built in 1928 with 40 units on five floors, with a mix of studios, and one and two bedroom units, will be worth what the tenants are paying today (and maybe a little more for expected rent growth). But the building is set in stone—and its income potentially is capped.[1] In short, the value of a building represents its value to the present owners.

It’s virtually impossible to know the underlying motivations of market participants, however, it is reasonable to conclude that in highly developed cities, like New York, Chicago, or San Francisco, buyers of buildings are typically buying for the present income, while buyers of vacant lots are buying for future income. Of course, this is a simplification, but the key point is that an empty lot in the city is worth nothing more than what a future building will provide. There is no oil or gold below the streets of Manhattan—only dirt and potential.

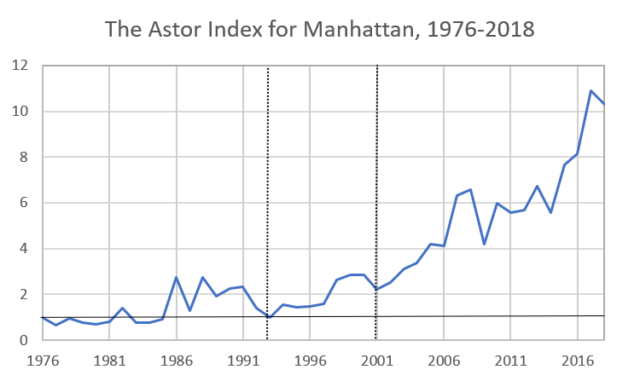

Introducing the Astor Index

All of this background gets us to the heart of the matter. If real estate prices represent present worth and vacant land prices represent future worth, we can compare relative changes in the two to determine which seems more promising. Thus, I would like to introduce what I call the Astor Index, in honor of John Jacob Astor. This index is computed as the ratio of the price of vacant land to the price of buildings. Here I present this annual index for Manhattan from 1976 to 2018.

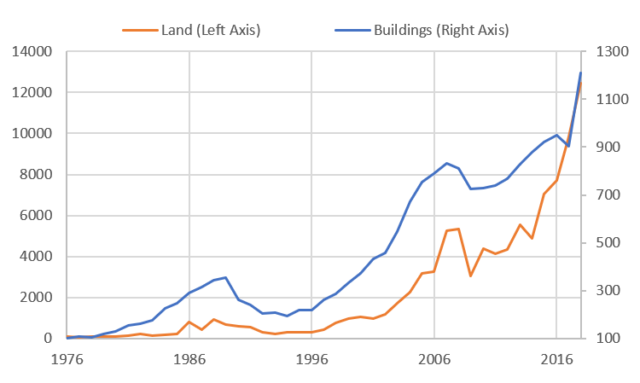

The index of vacant lot transactions comes from my research paper with Fred Smith (and updated to 2018). The buildings index comes from building sales provided by the New York City Department of Finance and processed by me. The figure below shows the values of the two (inflation-adjusted) indexes separately over time. The prices of both land and buildings have escalated in the last four decades. There was a run up in the mid-1980s, some retrenchment after that, but since the 1990s, both indexes have shown rapid appreciation (with a small setback after the Global Financial Crisis). But what about the ratio? What has happened to land prices relative to building prices?

The Downside

Before we get to the Astor Index for Manhattan, however, let’s pause to discuss the factors that are likely to affect it. That is, what is likely to determine whether land is more valuable than buildings or vice versa? Let’s start with the down. The index will decline when the future becomes increasingly uncertain or when the economy is doing badly. In this case, as the saying goes, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. While recessions may generate higher vacancy rates, buildings still generate income. Land, on the other hand, is riskier. The owner does not know when the down times will end. So while holding a vacant lot is costly, uncertainty means that the best option is to wait until the economic picture becomes clearer.

The Upside

But what drives a rising Astor Index? I can think of four reasons, though there could be more, and the ones below are not mutually exclusive. Implicit in all of them is that the local and national economies are strong so that developing the land will likely yield a higher profit. The first three relate to providing a building that generates more income as compared to surrounding buildings.

First is that developers can build taller. Second, they can build a higher quality building by adding high-end features and more amenities. Third, holding size and amenities constant, builders can provide structures more suited to modern tastes, such as with open floor plans or floor-to-ceiling glass windows.

The fourth reason is scarcity. As cities become developed, fewer and fewer vacant lots are likely to exist. The relative scarcity means that prices will go up. The vacant lots will be bought at prices based on who’s likely to occupy those spaces. In today’s urban environment those rare spots are likely to go to those with the most money, either wealthy households or businesses.

Self-correction

In a relatively free market, however, as something becomes rarer, market forces generally operate to reduce the scarcity.[2] As I have discussed elsewhere, the prices of important commodities, such as oil, wheat, and gold, obey this rule. When prices rise, indicating relatively scarcity, consumers purchase other related products and suppliers seek out new sources. The process of price spikes—eventually—leads back to lower prices and a better balance between supply and demand.

The price of vacant land, in theory, should be tied, in the long run, to the price of structures. Empty lots don’t just magically appear; they are produced like anything. Generally, they come from the removal of outdated or underutilized structures, like parking lots, flea markets, or taco truck stops. As land values rise, the benefit of holding an underutilized lot becomes lower and lower and is thus more likely to be offered up to the great flow of land in the marketplace. So, if building prices and land prices get “out of whack” then economic incentives should be present to move them back into relative harmony. If land values begin to escalate relative to building prices it suggests the presence of what economists call “frictions”: barriers preventing the conversion of underutilized lots into vacant land and then onto more profitable uses.

The Index

The figure below presents the Astor Index for Manhattan from 1976 to 2018. For ease of exposition, we can divide the index into two periods. Period I runs from 1976 to 2001. During this time, we see two things. First, the Astor Index stayed in a relatively constrained range. And second it was able to return back to one. By construction, the Astor Index is set to a value of one at the starting year.

Period I

From 1976 to 1985, the index remained, for most years, below one. The phenomenon is likely caused by two factors. First, the 1970s were hard times for New York. In 1975, the City defaulted on loans and needed to implement tremendous budget cuts. Reductions in policing and sanitation helped fuel a sense of despair, during a time when manufacturing jobs were also leaving in droves. The 1970s were arguably a low point for New York’s economy.

During this time, as property taxes were rising and rental incomes were falling, many landlords found it better to either simply walk away from their properties or to illegally employ arson to collect insurance payouts. As a result, the city found itself increasingly holding more and more vacant lots, especially in the historical tenement districts. In the 1980s, under Mayor Ed Koch, the city began selling these lots to developers, thus increasing their supply.

Starting in the late 1980s, the index shot up in the heady real estate market of the time. However, over-optimism lead to retrenchment. In 1993, the index was back at one. There was another run up in the 1990s until a downturn in 2001, but the uptick and the retrenchment of the 1990s were within historical bands.

Period II

I would argue that 2001 was the point of no return. Since then the Astor Index began its meteoric rise. Today the Astor Index hovers around 10, suggesting that land sells for a premium of 10 times that of buildings. But is this possible or realistic? I think so, since when we inspect Manhattan’s real estate, everywhere we see frictions. In a rising market, the low-hanging fruit of parking lots and highly underutilized lots will be offered up first. Then as they become developed, new land is created more slowly. Furthermore, given the economics of construction in New York, it’s more efficient to have a large lot. Assembling them can sometimes take decades and requires enormous patience. At any rate, it appears as if it’s becoming less and less possible for Manhattan to generate vacant land.

Land Uses in Manhattan

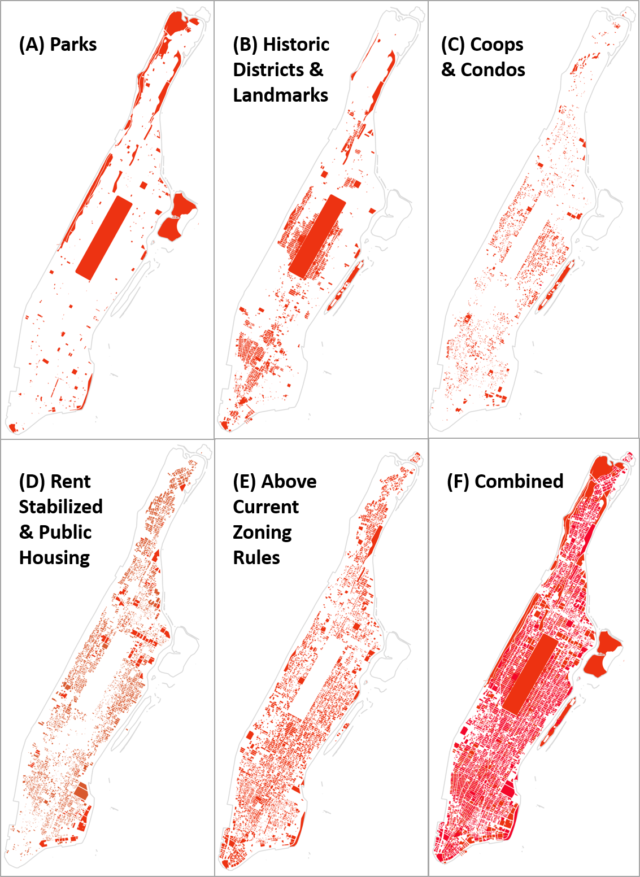

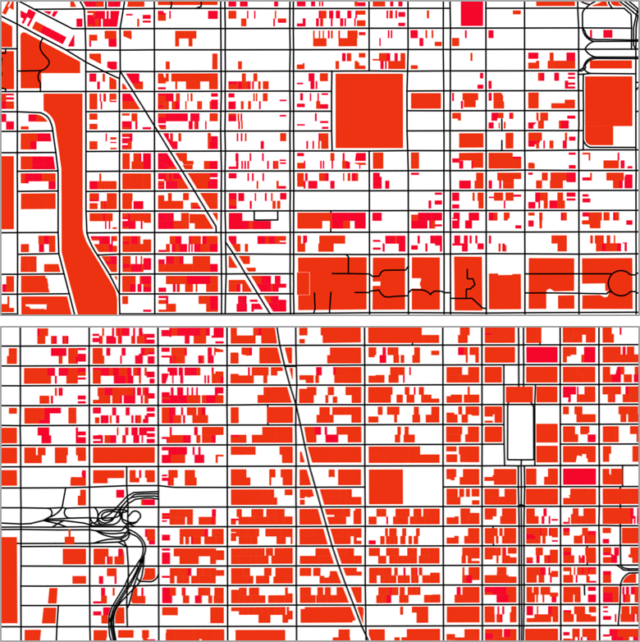

To illustrate this trend, the figure below shows the different land uses in Manhattan (as of 2016). Panel A shows the parks, playgrounds, and recreational areas. These areas are the vital lungs of the city and will not be developed. Next, in Panel B, are the historic districts and landmarked buildings (occupying 27% of Manhattan’s lots). Generally, these are buildings or areas that must be preserved the way they are. Their tear-down potential is thus very low.

Panel C shows those buildings that are coops or condos. These apartment buildings are owned by the occupants. In today’s climate, it is nearly impossible for owners to collectively decide to sell all their units to a new owner to tear down the building. Condos and coops make up 10% of Manhattan’s lots. Panel D shows buildings that have at least one rent stabilized tenant or are public housing. Rent stabilized tenants cannot (legally) be evicted. They have to right to remain in the apartment even if the landlord wants to empty it out (unless the landlord will occupy the unit herself). Again, this represents a very high hurdle to converting these structures to vacant land. Rent stabilized buildings occupy 30% of all Manhattan’s lots.

In sum, if we add up the landmarked buildings, the condos and coops, and rent stabilized units, that brings us to 67% of all lots on the island! Of course, this includes double counting between historic districts and tenant status. About 79% of rent stabilized buildings are not in a historic district or are landmarked (and let’s assume this value for condos and coops). This gives a ballpark figure of 55% of all buildings in Manhattan are either landmarked, condos or coops, or rent stabilized.

Zoning

New York City zoning rules dictate allowable building density. They limit the so-called Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which determines how many square feet of structure can be built per square foot of lot. For example, a FAR of 5 means 50,000 square feet of building area can be built on a 10,000 square foot lot (4,645 square meters on a 929 square meter lot). It’s up to the developer if she wants a 5-story building on the whole lot or a 10-story building on half the lot, for example. These rules, more or less, were established in 1961, though they have been modified to some degree across neighborhoods. However, in 1961, Manhattan already had substantial building development. In fact, 89% of Manhattan’s structures were completed before 1961, and 85% were built prior to 1941, with the majority constructed before World War I.

Many of these earlier structures were built more densely than the 1961 law allowed. They were, however grandfathered, as the density rules apply only to new constructions. Today, some 28% of Manhattan’s structures are denser than the law allows (Panel in E, in the above figure). If they were torn down, they would likely have to have less floor area than before—a great disincentive to tearing them down![3]

In total, back-of-envelope calculations yield the result that about two-thirds of all structures in Manhattan have some kind of “encumbrance” or friction that would make tearing them down much more difficult. So this means about only about one-third of lots are available for the land market, and of those many are smaller lots that need to be assembled into bigger ones before they would have value as vacant land.

Where’s Manhattan Headed?

While we currently don’t have a longer run Astor Index over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, it’s reasonable to say that an Astor Index of 10 (using 1976 as a benchmark year) is unprecedented and bad for society. It means that lots are exceedingly scarce and so their prices get bid up because they will be used for luxury condos. Today’s real estate rules promote income inequality and reduce access to more affordable housing. And yet, to most New Yorkers, rent and zoning regulations feel right. Supporters argue that they slow down income inequality and gentrification. But in truth, it has the opposite effect. By promoting stricter regulations, New Yorkers are unwittingly promoting in the very things they seek to prevent. This is likely to drive further increases in the Astor Index.

So what avenues are available? If New Yorkers want to keep Manhattan the same as Parisians want to keep Paris—frozen in time—then reform must be applied elsewhere in the city. An initial useful strategy would entail loosening the restrictions that create one- and two-family homes in the outer parts of the city. If these neighborhoods allow for medium- and low-rise apartments it would help reduce the price of housing in working-class neighborhoods. It would take some of the pressure off the Manhattan market and allow the city as a whole to be more affordable.

Another possibility is for the city to move toward a land tax oriented system. Here real estate taxes are based on the value of the land and much less (or not at all) on the building’s value. This should encourage tear downs, since current real estate tax rates discourage new construction by “penalizing” a more valuable building. But I’ll leave a more detailed discussion of these ideas for a future post. In the meantime, if Astor could see what his purchases are worth today, he’d likely try to rise from the grave and get in on the action.

I’m grateful to Maria Thompson for valuable editorial assistance.

—

[1] For the purpose of discussion, I’m oversimplifying. Clearly landlords frequently buy buildings with the intention of renovating or improving them in some way. But unless the building is torn down (or gutted), the structure’s income potential is arguably more limited than something built from scratch. Adding new floors to an old building is relatively rare and difficult.

[2] Here by “scarcity” I mean rareness, and not a shortage as is traditionally defined in supply and demand analysis.

[3] Today there are three ways to “circumvent” stringent zoning codes. First is via the purchase of transferable development (air) rights from neighboring buildings. In this case, a landlord with a building less than the maximum allowable FAR can sell the unused FAR to a developer who can increase the FAR of a new project. Second is by assembling a large lot a developer can keep a relatively modest FAR but still create a profitable high-rise tower. Third, in some cases the law allows a FAR bonus if the developer provides a public amenity, such as an open plaza or low income housing.

[…] implicação política dessa visão se resume a “Não no meu quintal!” — preservar as comunidades históricas em âmbar para mantê-las precisamente como Jane Jacobs as descreveu seis décadas atrás e banir edifícios […]