Jason M. Barr November 18, 2019

Across U.S. cities, perhaps nothing is more controversial than the issue of gentrification—the process of wealthier residents moving into lower-income, central city communities. Those who are against it claim it destroys cities and harms residents, while proponents say it helps neighborhoods grow and become livelier. So, which is it? Is gentrification good or bad? To answer this, we need to move beyond feelings and rhetoric and try to get a sense of what’s really going on. One of the best ways to do this is to employ rigorous social science methods with large data sets of individuals. This post highlights recent studies that that investigate what the data suggest about the consequences of gentrification.

The Key Findings

While we will review the findings in more detail below, if there’s one theme that runs throughout them, it’s that the terrible, sky-is-falling rhetoric on gentrification is not born out by the data—at least for the issues discussed here. Displacement—if it exists at all—is relatively slight. Luxury condos do not appear to promote rising rents for lower-income residents. On the other hand, gentrification can promote more diversity and integration and has little impact on children’s health. That’s not to say that gentrification is entirely benign or beneficial. The data do point to some negative consequences, such as a reduction in local employment and slightly higher anxiety levels among children. But taken together, the research suggests that gentrification in and of itself is not as harmful as its detractors claim.

The Bad

Those opposed to gentrification claim it promotes a series of negative impacts for residents. They say that it pushes up housing prices for the poor. As well, it irrevocably alters the vibe of neighborhoods—erasing its gritty, authentic soul with cold glass towers for the ultra-rich. Just as importantly, it drives the displacement of low-income families from their communities—forcing them to seek out cheaper shelter further away. Gentrification attracts expensive chain stores which don’t hire local workers, and who sell products that the low-income residents either don’t want or can’t afford. In short, opponents say gentrification is bad because it pits the lower-income incumbents against upper-income entrants, who always seem to win.

The Good

Proponents of gentrification might disagree on the degree to which it drives displacement and argue that an inflow of money is a good thing. With money comes resources and amenities. Older houses are renovated; stores that formerly avoided the area now bring in new products and services, as well as new employment opportunities. Money flowing into the neighborhood can only help—improving schools, reducing crime, prompting infrastructure upgrades, and so on. In short, gentrification is a tide that lifts all boats.

The Research

In the last few years, economists have begun to tackle the issue of gentrification using modern data-oriented research methods to tease out its causes and consequences. Here we are going to look at several possible impacts: displacement, neighborhood demographics and integration, children’s health, local employment, and high-end residential construction and housing costs. Specifically, I’m going to review six studies, four of which were written or published in 2019, one in 2017, and one in 2016. They represent the state-of-the-art work.

Experimental Design

With gentrification, residents feel like it’s bad. They see changes in their neighborhoods and rising prices, and they conclude that the influx of higher-income people must be the cause. But the problem with going with one’s gut is that it can lead to a confusion of correlation with causation. The key to seeing if there is a true gentrification effect is to establish a kind of quasi-scientific experimental design. The studies discussed below do this by going back to some starting period—say the year 2000—to first identify neighborhoods that are “gentrifiable” in that they are low-income, central-city neighborhoods.

From this pool, the researchers then place them into one of two “bins”—those that gentrified—i.e., saw big jumps in educated upper-income residents—and those that did not—i.e., remained relatively low income. In this way, the authors create a “treatment group”—those neighborhoods that gentrified—and a “control group”—those that did not. Then a possible impact of gentrification, such as employment opportunities or children’s health, can be investigated. The point is that we can’t make claims about gentrification without identifying a benchmark or reference group that has a similar conditions, except for gentrification.

All Else Equal

Another important aspect of this work is the use of regression analysis which allows researchers to identify a gentrification effect or not, controlling for or holding constant, a host of other factors that might determine some outcome. Cities are dynamic places. It’s hard to know how much of new employment opportunities or mental health issues are due specifically to gentrification, rather than the many other factors that are going on in people’s lives and their neighborhoods. The “controlling for” aspect that comes from the statistical methods allows for a gentrification effect to be better isolated among the “fog” of all the changes happenings on a day-to-day basis.

Gentrification and Displacement

Arguably, the most controversial issue about gentrification is that of displacement. When upper-income people move into a neighborhood, landlords—presumably—raise rents beyond what the low-income households can pay. They are thus forced to seek affordable housing elsewhere, either further away from the center or outside the city altogether. One of the main problems in trying to measure displacement accurately is that low-income households move quite frequently, independent of anything that might be related to gentrification. So, the objective is to measure how much of their movement is due directly to gentrification rather than from any number of other reasons that might have nothing to do with gentrification, such as the desire to be closer to family or changes in life circumstances.

Furthermore, if prices across the entire city are rising, people may leave their neighborhoods because of the general, citywide inflation in housing costs, which render their current homes unaffordable, and not for any specific localized reasons due to the wealthier entrants. By using regression analysis, researchers can decipher whether mobility is determined by gentrification per se or by rising prices more broadly.

Additionally, it’s theoretically possible that each time a low-income household leaves the neighborhood for reasons independent of gentrification, a high-income family moves in. In this case, no one is displaced. If this was the mechanism by which change occurred, long-time residents who see wealthy people moving in might draw the false conclusion that those who left were displaced, especially when the racial or ethnic composition begins to become noticeably different.

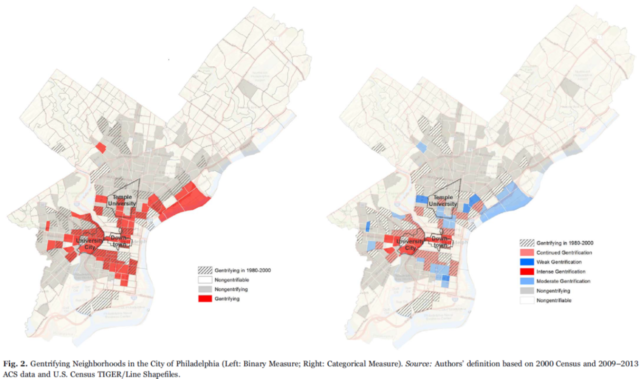

Philadelphia

Research by Lei Ding, Jackelyn Hwang, and Eileen Divringi, in their 2016 paper, “Gentrification and Residential Mobility in Philadelphia,” focus on the specific question of displacement. The authors obtained very fine-grained data for more than 50,000 adults living in Philadelphia between 2002 and 2014. The data set contains the census tract (usually a handful of blocks; and which comprises a small neighborhood) where residents were living and where they moved to (if they moved), and this can be exploited to determine how much of their mobility is being driven by gentrification.

The authors first define neighborhoods that are “eligible to gentrify,” or “gentrifiable,” if they had median household incomes below the citywide value at the initial time of analysis, in the year 2000. Then from this group, they define those neighborhoods as “gentrifying” if they experienced rapid increases in real estate values and in college-educated residents.

They investigate the likelihood of a resident moving from one census tract to another by comparing movement rates for those in non-gentrifying neighborhoods to those in gentrifying neighborhoods, controlling for a host of other factors, separate from gentrification, that might impact whether a person moves or not. Given their data set, they focus on residents without mortgages and who have low credit scores—which is a proxy for low-income, rent-paying residents. Based on their analysis, they conclude that

the results suggest that the low-score residents and low-score residents without mortgages in gentrifying neighborhoods are generally no more likely to move than similar residents in nongentrifying neighborhoods.

In short, they do not find strong evidence of displacement.

New York

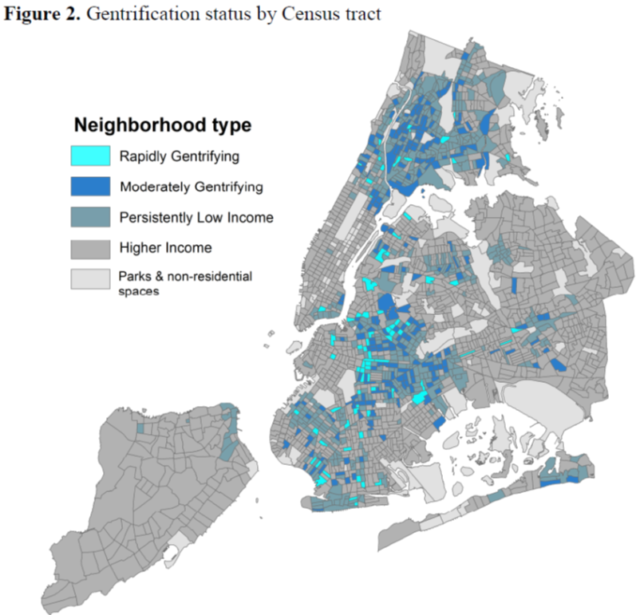

A paper with a similar approach, but for New York City, is “Does Gentrification Displace Poor Children and their Families? New Evidence from Medicaid data in New York City,” by Kacie Dragan, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Sherry Glied. In this case, the authors use fine-grained data from a New York State Medicaid database. Here the focus is on the possible displacement of children in low-income households.

Specifically, they use the database to track where 56,992 New York City children were living and whether they moved or not from 2009 to 2015. They were also able to determine whether they lived in public housing, subsidized housing (such as rent-stabilized), or free-market housing. In a similar spirit as the study above, they define neighborhoods (census tracts) as “gentrifiable” as ones that have average incomes in the bottom 40th percentile of all census tracts in New York City. Then from this group, they define those that gentrified as experiencing the most rapid growth of college-educated in-movers from 2009 onward.

The Findings

Comparing children in those census tracts that gentrified versus those that did not, they find that low-income children who were living in gentrifying neighborhoods were no more likely to move than children who lived in non-gentrifying census tracts. This finding holds even for low-income children who lived in market-rate rental housing. They also write,

Contrary to fears voiced by many, we find that the average low-income child who starts out in areas that later gentrify experiences a reduction in neighborhood poverty, mainly because the majority do not move as neighborhood income rises around them.

In short, the authors again do not find evidence of displacement, and they find evidence of improvements in the quality of children’s neighborhoods.

Gentrification and Integration

Most cities in the U.S. that appear diverse on paper are segregated in practice. At the very local level, people frequently live in neighborhoods characterized by high levels of racial or ethnic homogeneity. But gentrification has the potential to reverse this trend in the sense that it is normally associated with an influx of college educated white households into minority areas. The problem is that these in-movers are often seen as interlopers or invaders. Or as an Atlantic Monthly article put it, “The way a lot of African American and Latino people experience gentrification is a form of colonization. The gentrifiers are not wanting to share—they’re wanting to take over.”[1]

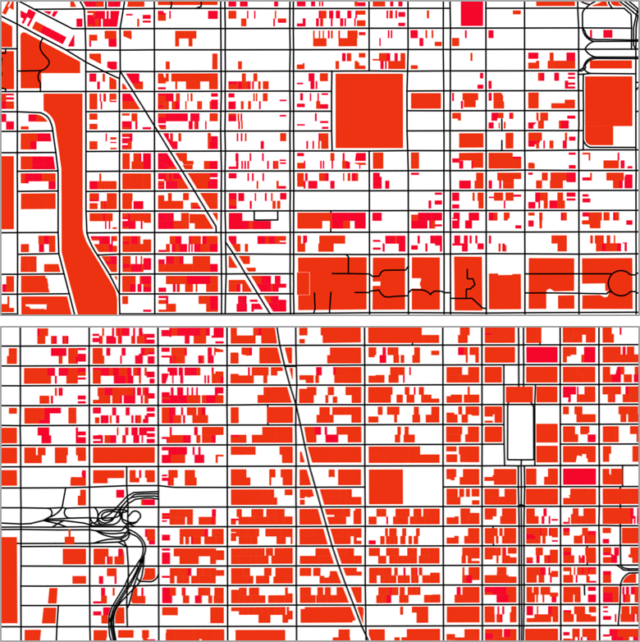

But, if, as most people believe, integrated communities are beneficial to residents and society, the question remains about how gentrification affects the composition of neighborhoods. The paper “Gentrification and Fair Housing: Does Gentrification Further Integration?”, by Ingrid Gould Ellen and Gerard Torrats-Espinosa, studies how gentrification impacts the racial and ethnic composition of inner-city communities. Here they investigate 412 cities throughout the United States. Similar to above, they define the set of low-income gentrifiable neighborhoods (census tracts) and then split them into those that gentrified versus those that did not, based on the growth in their relative incomes. They find that

the neighborhoods that have integrated through gentrification have remained racially integrated for longer periods of time than the conventional wisdom suggests. Many are seeing little change in their white population share in the decades following gentrification. Indeed, neighborhoods that became integrated through gentrification appeared to be more racially stable than those that integrated through households of color moving into predominantly white neighborhoods.

Gentrification and Local Employment

Another assumption about gentrification is that the wealthy interlopers bring in their expensive business, such as Whole Foods and Starbucks, and hire people from far away. But the question remains, how does the entry of new establishments in gentrifying communities affect employment opportunities for low-income locals? This question is investigated in “Does Gentrification Increase employment opportunities in low-income neighborhoods?“, by Rachel Meltzer and Pooya Ghorbani.

On the one hand, new businesses can generate opportunities for locals since they can see the “Help Wanted” signs as they walk past the stores, or they may be more likely to hear about new jobs from friends. On the other hand, if the new businesses require higher skills or less labor in general, or use in-house hiring mechanisms, as might be the case for large chains, then opportunities for locals may be diminished.

Here, the authors investigate the case of job growth in the New York City metropolitan region from 2002 to 2011. Similar to above, they first identify the pool of gentrifiable neighborhoods (census tracts) as those that are in the bottom 20% in the ranking of median household income in 2000. They then separate them into two groups—those that gentrified and those that did not based on income growth. Their focus is on studying what they call live-work zones—rings around each census tract that represent areas where one is within walking distance or an easy commute to work (they study three zone sizes, 1/3-mile, 1-mile, and 2-mile rings).

The Findings

Here the results are somewhat mixed. The authors find that jobs going to residents who live very close by decline (that is, jobs the within the same census tract or 1/3-mile zone). But, as the definition of live-work zone expands (to say within the one-mile area), gentrification is associated with higher employment going to local workers. They write,

We find that employment effects from gentrification are quite localized. Incumbent residents experience meaningful job losses within their home census tract, even while jobs overall increase. These job losses are concentrated in service and goods-producing sectors and low- and moderate-wage positions; but local residents do see gains in higher-wage jobs in very proximate live-work zones and lower-wage jobs slightly farther away.

In other words, employment effects are quite mixed. Closer to home, jobs seem to become less available to residents, but employment opportunities still exist within surrounding neighborhoods.

Gentrification and Children’s Health

One impact of gentrification that has not received much attention relates to children’s health. This issue is investigated in the paper, “Gentrification and The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City,” by Kacie Dragan, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Sherry Glied, who also authored the paper on New York City discussed above. For poorer families remaining in gentrifying neighborhoods, how do the young fare as wealthier people move in? Gentrification can potentially improve health because of increased safety, access to nutritious foods, better parks, and perhaps more healthcare itself, if new clinics or medical facilities move in. On the other hand, rapid changes might lead to more uncertainty and loss of friends, and children may see their parents suffer from financial stress and anxiety if prices rise rapidly.

Using the Medicaid data discussed above, the authors looked at four measures of children’s well-being: obesity, asthma, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety or depression. Again, similar to the other studies, they compare gentrifying neighborhoods to those that did not.

They find that

children who started out in areas that rapidly gentrified in the period 2009–15 did not differ meaningfully or significantly from children in similar areas that remained low SES [socioeconomic status] in terms of their 2015–17 rates of hospitalizations … or in terms of diagnoses for overweight or obesity, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or conduct disorder, or asthma at the end of the period (by ages 9–11) However, the difference between the two groups of children with respect to anxiety or depression diagnoses was significant: We saw a 1.56-percentage-point increase (8.69 percent versus 7.13 percent; p < 0:01) in the prevalence of anxiety or depression among those who started out in areas that rapidly gentrified relative to those in areas that remained low SES.

In short, they do find a bump in anxiety rates, but otherwise, no other differences. The drivers of this increase is not explored, but it is an important question for future work.

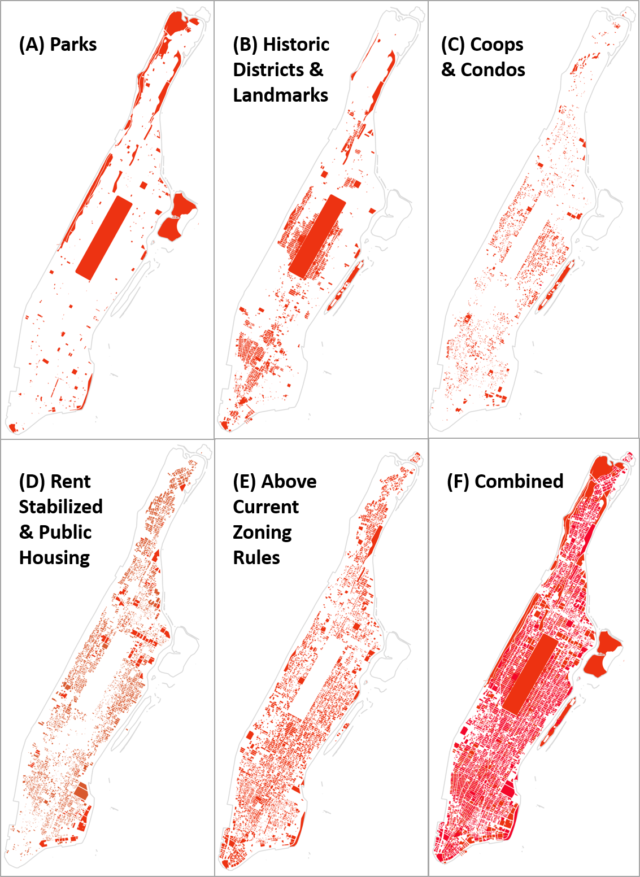

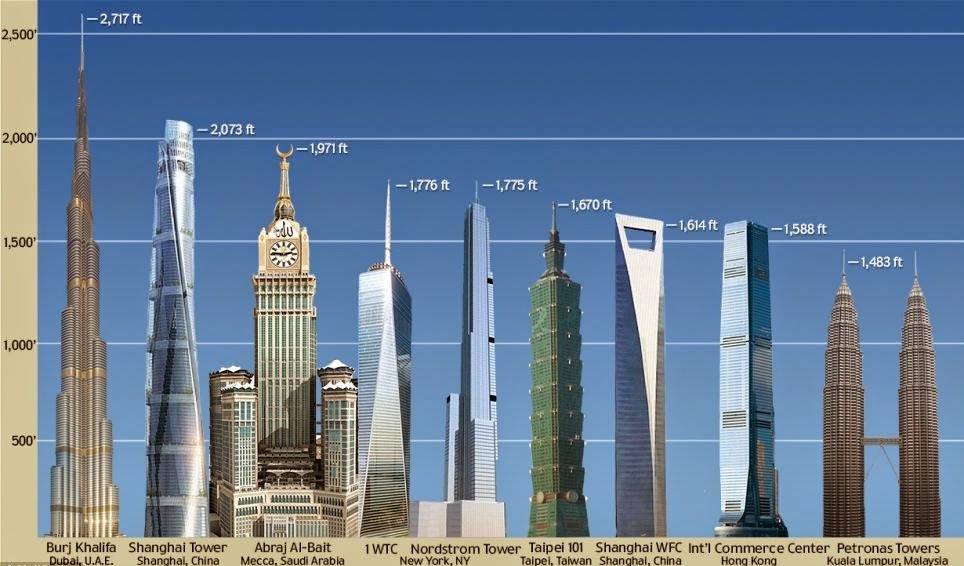

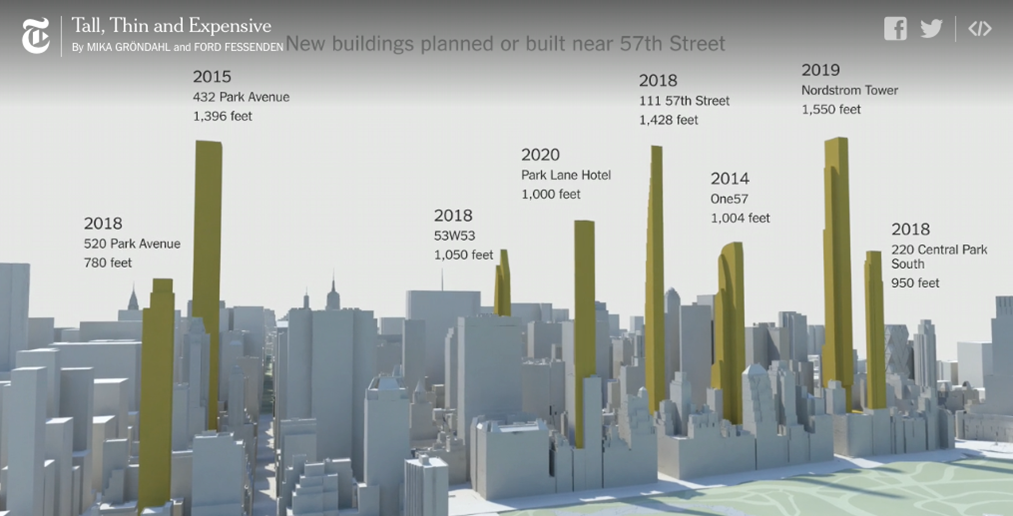

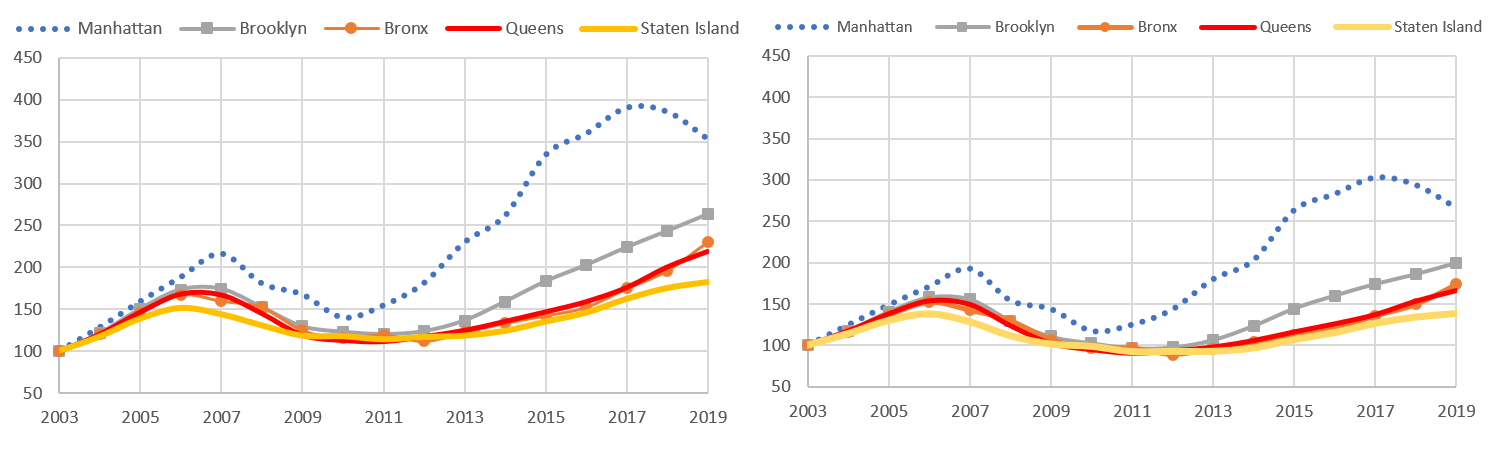

Gentrification and Housing Prices

Lastly, gentrification is a hot-button issue because the assumption is that when high-end construction appears, it means rising prices for everyone. A recently-completed study by Xiaodi Li, “Do New Housing Units in Your Backyard Raise Your Rents?“, explores how the construction of high-end residential buildings impacts rents in nearby buildings across New York City from 2002 to 2013. The Law of Supply says that as more units are built, it will increase the total quantity of housing and thus lower prices, all else equal. The demand side relates to the spillovers associated with new construction—if the high-end units also draw in more amenities or help reduce crime, for example, then people would be willing to pay more for housing in these places, and prices will rise. Li’s goal is to separate these two elements and see which is more important.

The Chicken or the Egg?

The measurement problem here is to disentangle a kind of chicken-and-egg conundrum: do rising rents drive new construction, or does new construction drive rising rents? To investigate the latter, Li controls for the timing of new construction by looking at both when new a building permit is issued and when it opens up for occupancy. The idea is to look at how rents are impacted by building openings, controlling for the permitting dates. Openings represent the supply effect, where the permitting times can control for the draw of the neighborhood if it is gentrifying. Another measurement strategy she uses is to focus on how rents are impacted only within 500 feet of a new building. By looking at very localized relationships, she can more accurately calculate price changes due to new completions, rather than other things going on in the neighborhood or city.

The Findings

Based on her analysis, she concludes that

for every 10% increase in the housing stock, rents decrease 1% … within 500 feet. In addition, I show that new high-rises attract new restaurants, which is consistent with the hypothesis about amenity effects. However, I find that the supply effect is larger, causing net reductions in the rents and sales prices of nearby residential properties.

In other words, her results validate the Law of Supply, which says that adding more housing can help reduce prices. It is important to remember, however, that the statistical method finds a reduction in rents from new buildings, holding everything else constant. But, in reality, everything else is not fixed. In particular, prices across the city are, in general, rising. So based on casual observation, it’s virtually impossible to mentally calculate how much prices would have grown otherwise, if there were no new additions.

Concluding Remarks

Though taken together, these studies find minimal impacts from gentrification, I have, due to space constraints, necessarily given short shrift to other elements of these scholars’ research. I do not want to give a false impression that each study only finds the one thing that I reported. Instead, each uses their data sets to study details and questions beyond what I have discussed. Their work teases out more nuanced impacts. I hope to return to these issues in a future post.

The Mechanisms?

These studies, however, generally do not identify the underlying processes or mechanisms that are in play. It calls to mind the need for additional studies. We can imagine any number of reasons why displacement effects are not being found. For example, cities with rent control or public housing might protect low-income residents and so what is being measured are the protections (though Dragan et al. find no higher rates of displacement in market-rate homes). Furthermore, gentrification is often associated with high-end construction. So, the lack of an impact may be from entering residents living in new units or moving into housing that becomes vacant through normal turnover.

But we could also envision that a displacement effect is being muted by an equally opposing “stay-at-any-cost” effect. For example, we can imagine two sets of low-income households in a gentrifying community. First are those who refuse to move, despite rising costs, because they prefer the new neighborhood or believe it’s better for their children. They thus absorb the expenses and pay them through either working more hours, taking in roommates or lodgers, or reducing expenditures on other things. And then we can imagine another set that is priced out or no longer likes the neighborhood and leaves. So here we might not see any net effect because the must-stayers equally balance those displaced.

More to Come

The findings reviewed here are but a few that look at the impacts of gentrification. In future posts, I will discuss more of them, as well as studies that look at the drivers of gentrification. As a whole, this body of work can also aid city officials in designing better policies that help those harmed without generating unintended consequences. There is still much to discuss. Stay tuned.

—

[1] This quote is reproduced in Ellen and Torrats-Espinosa’s article discussed in the section, but the original 2017 article in the Atlantic Monthly is here.