Jason M. Barr November 19, 2020

In the 21st century, Planet Earth has gone on a skyscraper building spree. Since 1995, for example, the number of skyscrapers (150 meters or taller) completed each year has grown at a rate of 8.8%. The height of the tallest completed building has risen at an average annual rate of 2.5%. In short, tall—and taller—buildings have been in great demand. Then on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 Pandemic. How will it affect the market for tall buildings? And what does the market tell us about the future of our cities?

Economic Impacts

In many respects, skyscraper construction is a bellwether for the health of our cities. After all, virtually all skyscrapers get built in big metropolises. Most of those are in central areas where people and businesses come together to generate new ideas and new products. If they stop doing these things, then the future for skyscrapers would seem rather bleak.

Skyscraper construction is not only about housing a city’s activities but also gives something back to the economy. Construction generates income for construction workers, and fees for the architects and engineers and so on, and ground-floor retail can aid small businesses and restaurants. In New York City, for example, construction each year directly contributes to about 2.5% of the city’s gross domestic product, but indirectly contributes much more through multiplier effects—where each dollar earned by a construction worker gets spent on local goods and services, which gets spent on other local goods and services, and so on. A typical skyscraper in New York City costs a billion dollars or more, and the city normally employs about 135,000 people in the industry.

A Juggernaut?

Skyscrapers, however, can take many years between conception and completion. Even before the first shovel is dug these projects are likely to have been in the process for several years. Developers must buy the lot, arrange financing, file for permits, have the building designed, consult with engineers about structural and geological issues, then put out bids for construction and supplier contracts. Once these are done, few have an incentive to halt the processes, though they can certainly slow things down.

Furthermore, skyscrapers are long-lived. Few structures above 100 meters are demolished. So once a developer begins the project, she has the incentive to see it through. Even if it opens mostly empty, the building should be profitable in the long run. The key in a crisis is to fill it just enough to pay the financing and operating costs.

Thus, even during a pandemic, skyscrapers are likely to continue to be built once begun. But at some point, projects get shelved, construction efforts slow, or those only half-built get topped out earlier than originally planned.

COVID-19 and Construction

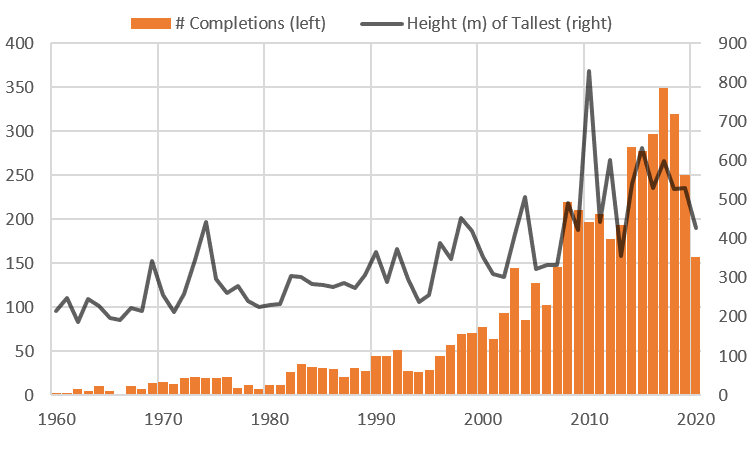

How has the COVID-19 Pandemic influenced skyscraper construction around the world? To answer this, let us take a long-run view. Historically, the U.S. dominated in the skyscraper market. But things began to change toward the end of the 20th century. Using data from the CTBUH Skyscraper Center, Figure 1, shows the number of skyscraper completions (150 meters or taller) and the heights of the tallest completed building from 1960 to 2020. Around 1995, we see a sharp uptick, about when mainland China started building skyscrapers in earnest. In the peak year of 2018, the world completed 349 skyscrapers (150 meters or taller). 2019 was lower, and 2020 will be even worse.

This year will see a sharp downturn—to around 157—but the completions count is still on track to be higher than in the mid-2000s, similarly, for the height of the tallest completed building. In the 1960s, the tallest completed buildings tended to be in the 200-meter range. Today 200 meters is puny. And since 2010, typically, the tallest structures are above 500 meters. This year the tallest building will be well below that but will still be extremely tall, at 427 meters (59 floors).

Predicting Skyscraper Construction Around the World

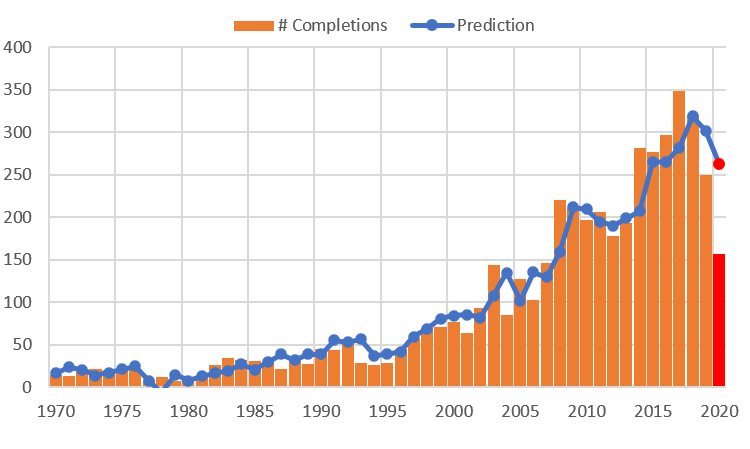

But what is likely to happen in the years to come? Before we start to make some predictions, it is necessary to investigate the fundamental drivers of skyscraper construction worldwide. To this end, I have created a relatively simple statistical (regression) model that can substantially account for the growth of the number of tall buildings and the heights of the tallest building (details here). The model, of course, cannot predict things with 100% accuracy. The point of this exercise is to see if we can parsimoniously explain why skyscrapers get built and then use this model to make some predictions about the near future.

From this model, two key variables can help explain why both the number and heights of tall buildings have been growing over time. First is world Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (inflation-adjusted), which has grown 343% since 1970 (that is, the world economy is 3.4 times greater today than fifty years ago). Second is the global urbanization rate, which in 2019 was 55.7%, as compared to 36.6% in 1970.

The two variables are strong predictors of skyscraper construction patterns, suggesting that skyscrapers have a strong economic rationale—even among the tallest of the tall. Their construction is driven by the need for people and businesses to cluster in central cities. However, since construction decisions are made in the past, it is necessary to account for these lags. The statistical procedure can indicate the best time fit between skyscraper completions and the economic variables. It shows that world GDP growth and urbanization rates three years prior are the best indicators of completions and heights, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the growth in skyscraper completions over time alongside the statistical model’s predicted number of completions. The orange bars give the actual completions count, while the blue line is the expected value. One can see a pretty good fit between the two, on average.

China’s Policy Changes

The model gives predictions for what is expected to happen based on events in the recent past. But it does not predict things exactly. There are several reasons for this. First is randomness; nothing can be predicted with 100% certainty since many tiny things change from year to year and project to project. Second are significant events that take place outside the model (and are often not modellable). China, which has been on a skyscraper building spree, has pulled back a bit, and this was noticeable in 2019. To quote from a report by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH):

It is tempting to read the noticeable drop in completions [in 2019], particularly in China, as a sign of the effect of proximate events, such as the trade negotiations with the United States, or as the harbinger of a recession. It is well-documented that many of China’s tall building projects were financed with high levels of debt, and that in recent years the government has attempted to rein in speculative building and investing. Certainly, the overall momentum of construction on the very tallest buildings in the world’s most populous nation appears to have slowed on a year-to-year basis. However, as always, it must be remembered that skyscrapers are lagging economic indicators – many of these towers were conceived and initiated five or more years ago, and thus reflect the development circumstances of a half-decade prior.

Additionally, in June of 2020, the Chinese central government placed a ban on 500-meter or taller buildings and required vetting of those 350 meters or above. In the near future, this policy will reduce the total number of skyscrapers completions (or it might increase the number of buildings below 350 meters).

The COVID-19 Effect

Then, of course, is COVID-19, which was utterly unpredictable. In this case, the downturn reflects those who have either topped off their structures below 150 meters or delayed completion until next year. In the absence of COVID-19, the model predicts that there would have been around 263 skyscrapers this year, nearly 70% more than what we will see by year’s end.

Beyond 2020

Ultimately the long-run upward trajectory for skyscrapers is likely to resume within a few years. First, those developers who delayed construction because of COVID-19 are likely to continue or speed up completion in 2021 as vaccines start to get distributed. But more fundamentally, there likely seems few long-run changes in the economic and social path that the world has taken. Since 2000, real world GDP has grown at an average rate of 2.4%, and this pattern is likely going to resume next year; that is the view of Deutsche Bank. Given the lag in construction, this means that skyscraper growth is not likely to hit its 2018 or 2019 levels until 2023 or so. Furthermore, world urbanization has, on average, ticked up about 1 percentage point every two years since 2000. Again, there is every reason that this trend will continue, even if hyper-density is checked somewhat because of fears about the virus. The fact that skyscrapers respond so directly to urbanization and global economic growth suggests the future remains on the up and up.

The Case of New York

We now turn to the specific case of New York City. In the early days of the pandemic, New York was the epicenter, and its density was blamed for the virus’ rapid spread. Today, New York is one of the relative bright spots as the virus has moved on into the interior and rural parts of the country (thought the region is still suffering).

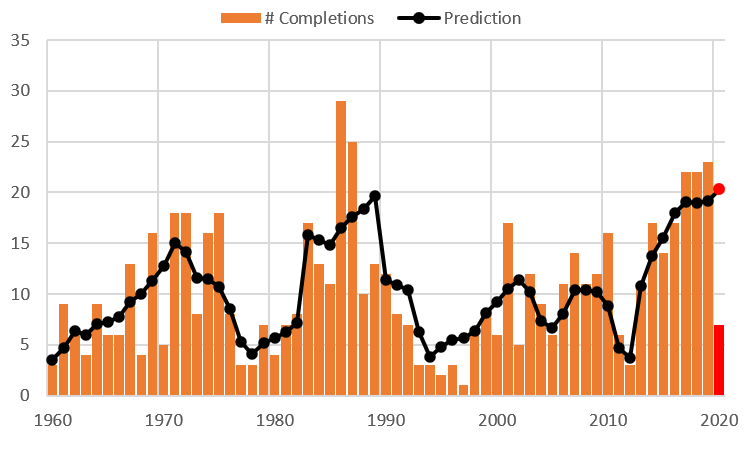

Here, we can look at how construction and heights are affected by local variables, with a focus on buildings that are 100 meters (about 30 stories) or taller. The long run patterns for the city shows something different than the rest of the world. New York’s growth is cyclical, with long upward ticks, followed by sharp declines and so on, but with no sharp upward trend like the rest of the world.

Because New York has been developing skyscrapers for so long, new buildings are added more slowly than in the rest of the world, where many cities are getting into the game for the first time. New York has seen five major cycles since World War I: The Roaring Twenties, Post WWII modernization, the 1980s office boom, a 2000’s condo and hotel boom, and then another one after the Financial Crisis of 2007-8. In terms of the heights of the tallest buildings, between 1955 and 2000, heights were generally around 200 meters; in the 21st century this has risen to about 300 meters, but remain well below the world average of around 500 meters. The ultimate question, however, is: is New York done building skyscrapers?

Economic Analysis

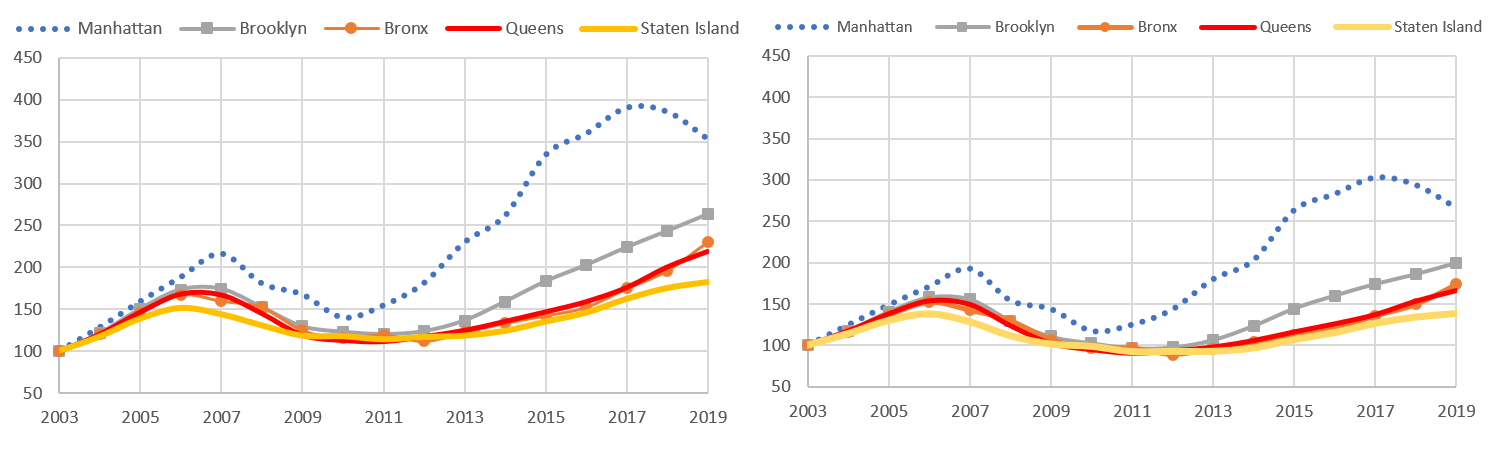

For the entire world, we can “explain” skyscraper growth by the two key variables of world GDP growth and urbanization rates. We can do something similar here, as well. But by looking at one city, we can use local factors to get a more fine-grained analysis. To this end, a “simple” New York City model includes total New York City employment, the value of the stock market (as measured by the S&P500 Index), interest rates (the Fed Funds rate), and a construction cost index (the Turner Construction Cost Index). (Data sources and results here.) Similar to the analysis for the world, the best “fit” for these predictors are from two or three years past, given the long timelines for these projects.

Figure 3 shows the number of skyscrapers since 1960 and the model’s predictions. Overall, the model can capture the broad trends and cycles. For 2020, the model predicts that there “should” have been 20 skyscraper completions in New York City, as compared to the likely number of 7—a nearly 300% drop!

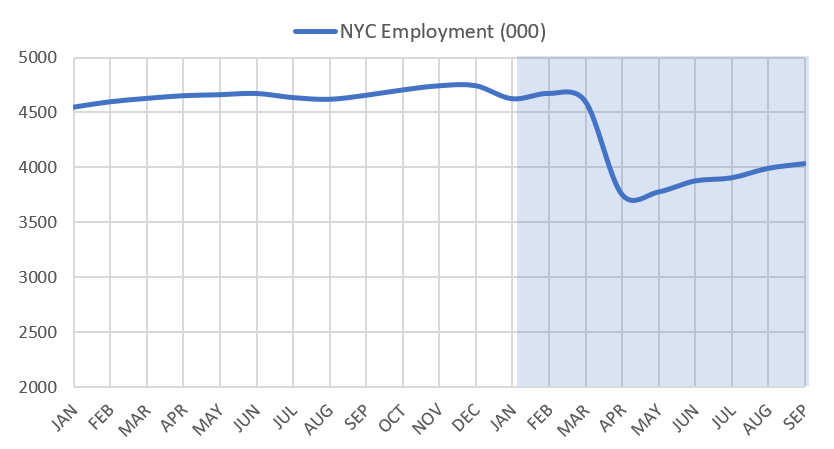

Among the group of predictors, the most important is New York City employment two years prior. An increase a 10% increase in jobs in a given year is associated with about eight more skyscrapers two years later, on average. As Figure 4 shows, New York City employment took a massive hit at the beginning of the pandemic. In February 2020, employment peaked at 4.67 million jobs and collapsed by nearly 20% by the end of May. It has since begun to rebound but remains well below that of earlier in the year.

Therefore, the near term of New York’s tall building market depends on what happens to employment. If 2021 shows a rapid rebound, we will likely see construction patterns return to pre-COVID-19 levels by 2023. Otherwise, things will be delayed until mid-decade.

The Death of Tall Buildings?

It seems that every time a crisis hits our cities, there’s a chorus of voices shouting that this is the death knell for skyscrapers. After 9/11, the skyscraper was pronounced a thing of the past. After the financial crisis and global recession in 2007-2008, cities were considered overbuilt. Now people are saying that density is bad and nobody will want to return to the office ever again.

But the fundamental truth is this: the world needs its cities. We are social creatures and we rely on proximity to make our economies function and grow. This growth means an increasing reliance on cities, which means a need for more skyscrapers. In this sense, the long run prospects for tall buildings remain strong.