Jason M. Barr March 28, 2022

Today, metropolises like New York, Vancouver, and London, get a lot of flak for constructing ultra-luxury high-rise condos for international jet-setters. They seemingly have become “safe deposit boxes” for billionaires. Whether these structures are good or bad for cities is worthy of debate, but it does raise the question about skyscrapers more broadly and their role in urban growth. Why are these cities such magnets for real estate investment in the first place? Ultimately, I would argue, it’s because of the strength of their economies and their broad offerings to residents and visitors alike.

New York and Chicago’s historical skylines emerged “spontaneously” as their land values hit thresholds, incentivizing the construction of tall buildings, each of which is “merely a machine that makes the land pay.” London, which rejected skyscrapers for many decades, has recently been pulled into going tall and is now awash in Gherkins, Cheesegraters, Walkie Talkies, and Shards.

Field of Dreams

On the other hand, some cities, especially in Asia, have seemingly used skyscrapers as a so-called Field of Dreams strategy—if you build it, they will come. Arguably, this began in Kuala Lumpur, which constructed the world’s tall buildings, the Petronas Towers, in 1998, at 88 stories each (1483 ft, 452 m). The city used these record-breakers as a part of a three-prong strategy: Provide office space for Petronas, the state-owned oil company; redevelop an abandoned racetrack into a bustling neighborhood; and announce that Kuala Lumpur is “open for business.” Thus, the Petronas Towers was a direct attempt by Kuala Lumpur to join in, and benefit from, the global economy.

Dubai

Perhaps no other city has so fully embraced the skyscraper as an economic development strategy as that of Dubai. The conventional wisdom is that Dubai is an instant city and that its towers emerged overnight like mushrooms after a rainstorm. But this is not entirely true. Dubai, which came relatively late to the oil game, had invested in trade and its port since the 1950s.

Despite the perception that the Burj Khalifa is a pure “ego play,” Dubai has been building skyscrapers since the late 1970s. Its first skyscraper was the Dubai World Trade Center, modeled, in large part, after New York’s World Trade Center. Though quite diminutive compared to its New York cousin, it was the Middle East’s tallest building for many years.

In 2002, when the city allowed property ownership by non-nationals, it generated a flood of investment because of its global and urban status. The demand for luxury high-rise towers emerged from Dubai’s strong economic position and tourist and leisure opportunities.

China

Then there’s China. Since it initiated economic reforms in 1978, mainland China has embraced skyscrapers like no other country. Today, it has more tall buildings than any other nation and is home to nine of the world’s 20 tallest skyscrapers. And tall buildings do not just appear in big metropolises but in small and medium cities as well. The country’s building spree is due to its rapid urbanization and its unique governance structure, where local officials are charged with planning and building out cities in anticipation of future growth.

The development of the Pudong area in Shanghai is an example of using skyscrapers to enhance a city’s global position. By building some of the world’s tallest structures, including the Shanghai Tower (2015, 2073 ft, 632 m), the city aims to increase foreign direct investment (FDI), provide office space for international firms, and get that much closer to becoming the “Wall Street of the East.”

So, when we look at skylines around the world, we seemingly have two different models: “spontaneous eruption” versus “Field of Dreams.” Which is the actual nexus between skyscrapers and city importance? Here we focus on one key measure of urban importance: global connectivity—the degree to which each city is connected to other cities worldwide. Does global connectivity drive skyscraper construction, or does skyscraper construction drive global connectivity? And can a city leapfrog its way to the top by building a supertall skyscraper?

Global Cities

We can look at the Global Network Connectivity (GNC) index from the Global and World Cities (GaWC) Network to measure global connectivity. The index, which measures urban interconnectedness, was first created in 1998 and has been updated regularly.

Thus, the data measures the “centrality” or connectedness of several hundred cities to get a sense of the degree to which they linked to each other or not (see here for more details). The basic idea is to measure the importance of a city’s office-based sector by looking at the number of international business services and financial offices. The top-tier global cities will have local headquarters for international firms, while lower-tier cities will have smaller representations of foreign firms. By counting the size and importance of these business, the index measures how economically connected each city is to the rest of the world.

One key finding is that London is the global champion and has held the top position since the index was created. In 2000, the top five were London, New York, Paris, Tokyo, and Singapore. In 2020, the top five were London, New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai.

A Look at the Data

The first question to investigate: Are skyscraper construction and global connectivity linked? If there is little relationship between the two, it would suggest that skyscraper construction is not directly related to the economic fundamentals of a city or rather is only loosely connected. Then we might need to look for other reasons for their construction. To investigate this question, I have obtained two types of data. One is on skyscraper construction for cities worldwide, and the other is city scores from the GNC Index. (Information about data sources and preparation is here.)

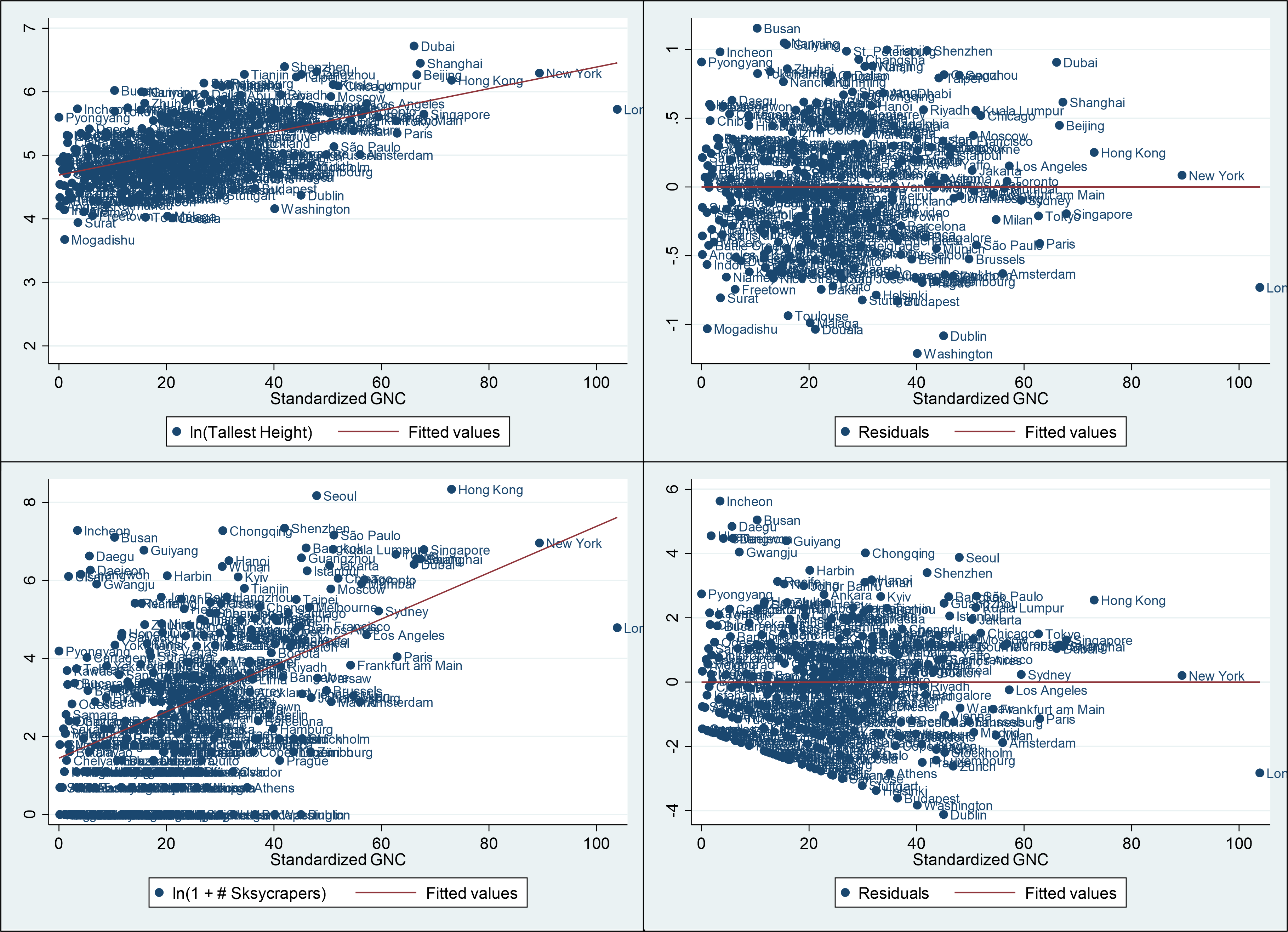

Do globally connected cities tend to have more or taller skyscrapers than their less global counterparts? The answer is a definite “yes.” We see a strong positive relationship between the height of a city’s tallest building and its GNC score (see figures below). While the correlation is not perfect (ρ=0.53), it does provide evidence that, on average, more connected cities have taller buildings. Going from a city with a median GNC score to one in the top 75th percentile means, on average, a jump in its tallest building by about 37 meters (about ten floors).

What about the number of skyscrapers, where here a “skyscraper” is a building that is 90 meters or taller (295 feet, about 30 floors)? Again, we see a similar pattern: on average, around the world, skyscraper construction and global connectivity are strongly related (ρ=0.49). The data show that going from the median GNC score to the 75th percentile (about 10 GNC points) is associated, on average, with an increase of about 80% more skyscrapers.

Outliers

The graph, however, shows some interesting outliers. London, the most globally connected city, is way below the trend line for skyscraper growth and has somehow managed to get to its number one position without having a history of tall buildings like New York or Hong Kong. Two other cities stand out as interesting: Dublin and Washington DC.

However, before discussing outliers, they should be considered after “detrending”; that is, how far away from the pack they are after comparing what one expects given their global connectivity scores (see the figures below). Here we see that Dublin and Washington are, indeed, the furthest below the trend line. That is to say, the heights of their tallest building are much shorter than what would be expected. This makes sense for Washington DC since it has a height cap, where not building can be taller than the Capitol Building. Dublin refuses all tall buildings and limits its building heights to 60 meters (197 feet) in most of the city.

London

How can we explain London’s high GNC score but low skyscraper score? This question requires a fuller treatment, but the answer, I would suggest, lies in its long history regarding capitalism and the Industrial Revolution. London began its global ascent as the UK simultaneously pursued imperialization and industrialization. These two created positive feedback loops that gave London a central position in the global economy, even before skyscrapers were technologically feasible. As a result, it seems to have developed an ability to run its affairs and accommodate global investment without going tall. In addition, the City of London is less land constrained than other central business districts like Manhattan or Central in Hong Kong. Evidently, it was able to expand outward in place of building upward.

Dubai

Looking at the outside of the trend line, we see that Dubai’s “outlierness” is not as extreme as it might seem. Even though it currently holds the record for the world’s tallest building, its rank in the GNC Index is relatively high; in 2020, it was at #7 (out of 707 cities). In fact, Shenzhen and St. Petersburg have even taller buildings than their GNC index values would suggest. And the city with the highest deviation from the trend is Busan, in South Korea, which, though not highly globalized, is still an important city in that country.

Leapfrogging?

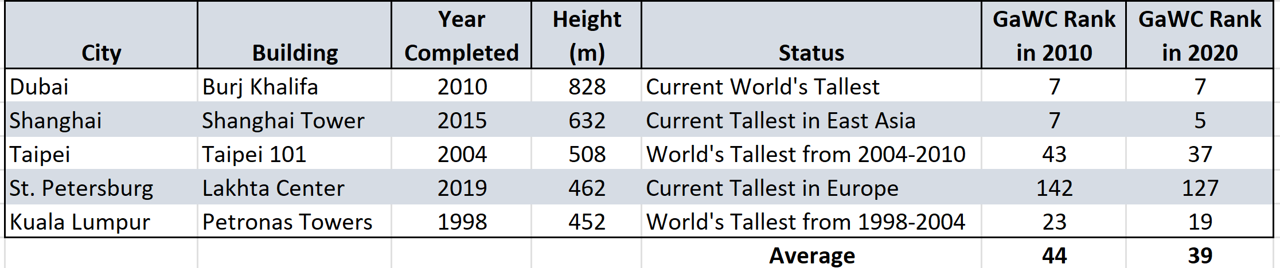

Returning the “Field of Dreams” theory, the question is whether constructing the world’s tallest building can leapfrog a city into global prominence. Cities jump into the world record game, in large part, to advertise and demonstrate they are open to FDI and tourism. Despite what seems an unyielding quest to have the world’s tallest building, since 1998, the record has only been beaten three times: the Petronas Towers in 1998, the Taipei 101 in 2004, and Burj Khalifa in Dubai in 2010.

The data in the GNC data set that I have goes back to 2010, making it a bit difficult to draw conclusions about the first two and whether they saw dramatic leaps in their rankings just after opening. Nonetheless, we can look at the changes in the GNC rankings since 2010 to see if there are dramatic changes. In this example, I looked at five cities. The first three are Kuala Lumpur, Dubai, and Taipei, which each have or had the world’s tallest buildings. I then added Shanghai, with East Asia’s tallest skyscraper, the Shanghai Tower (2015), and St. Petersburg, with Europe’s tallest skyscraper, the Lakhta Center (2019, 1516 ft, 462 meters).

This exercise shows that, on average, these five cities moved up in the global cities rankings between 2010 and 2020, but there were no major jumps, and each remained roughly in the same tier that it had been before. It suggests that cities can use tall buildings to make relative improvements, but in no case do any of them see massive leapfrogging.

Another statistical test is to see if a broader set of cities with very skyscrapers have witnessed dramatic leaps in their global rankings. To this end, I compared average changes in GNC scores between 2010 and 2020 for cities with the tallest building in their respective country in 2010 versus those that don’t. The statistical results suggest that countries with the tallest buildings improved global connectivity scores faster, on average by about one GNC point (results here). At a minimum, it indicates that leapfrogging is not supported, and that more subtle mechanisms are at work. A further test for GNC growth in the last three years for buildings with and without the country’s tallest shows that the non-tall group outperformed the tall group, suggesting that other factors besides tall buildings are at work.

Causality?

We still need to drill down to the causal link, however. Just because there is a correlation between global connectivity and skyscraper construction does not mean there is a causal relationship. We don’t know if, on average, global connectivity leads to more skyscrapers, more skyscrapers lead to greater global connectivity, or if the relationship is just a coincidence and driven by their connection to some other variable, such as a city’s gross domestic product.

To this end, I dug deeper into the data to see if there was evidence for a causal connection. Here, I performed a series of statistical (regression) tests to see if the two might be linked, controlling for other variables that are likely to drive each of these variables. (The data sources and regression results can be found here.)

Does Higher GNC Lead to More or Taller Skyscrapers?

In my statistical analysis, I first looked at how the height of a city’s tallest building was impacted by its global connectivity score and other control variables, including a city’s population and its gross domestic product (and other variables). The takeaway: I found that an increase in GNC score by 15 points (one standard deviation) increases the height of the tallest building by about 7%, on average. Not a large number, but, still meaningful.

A similar result was found for the number of skyscrapers. On average, after controlling for a host of other variables, including each city’s population or urban GDP, there remained a positive and statistically significant relation between the GNC score and the number of skyscrapers a city had. On average, a 15-point rise in GNC score was associated with 75% more skyscrapers, a substantial impact.

Does Skyscraper Construction Lead to More Global Connectivity?

Flipping the question: Does skyscraper construction lead to more global connectivity? Again, the answer is “yes.” Controlling for GDB and other city variables, a 10% increase in skyscraper counts, on average, increase the GNC index score by about half a point. Seemingly not a large number, but one that does suggest a connection. While estimates of the impact of a city’s tallest building vary across different regressions, the results suggest that cities with taller buildings also have higher connectivity scores.

Linkages

Based on the results of the statistical tests, what can we conclude? First, the Field of Dreams theory is not supported. Instead, emerging cities with a global presence can use skyscrapers to improve their relative global position. But they cannot turn a small, isolated village into an urban juggernaut overnight. Instead, supertalls are used to aid and abet the quest for global status, but this cannot be done without the other economic and institutional factors.

While the degree of “spontaneous eruption” across cities requires more research, we can see a positive feedback loop between skyscraper growth and economic interconnectedness. As cities become desirable places to live in work, they need to have the kinds of buildings that facilitate these activities. Tall buildings play a role in allowing providing spaces for this activity. And they also help advertise cities and build confidence in the place.

Thus the results suggest a bi-directional relationship between economic growth and the nature of its building stock. If city leaders want to increase their global competitiveness, they must aim to create policies that attract FDI and high-skilled workers and allow their real estate stocks to expand accordingly. More investment leads to taller buildings, which generates more investment, and so on.

While skyscraper construction has its share of controversy and doubters, the evidence strongly suggests that cities are better off when they allow for needed tall buildings.