Jason M. Barr January 10, 2024

The billion-dollar question: What’s driving the housing affordability problem in large cities like New York? When looking to cast blame, people naturally pick developers. Clearly, the conventional wisdom goes, they are making the problem worse because all they do is build unaffordable luxury high-rises.

Developers will argue, however, that given the high cost of land, the only way to make their investments work is to create a building that will produce enough revenue to pay for itself and the cost of land. Thus, high land values drive the affordability problem.

The “blaming the land” idea was recently stated in a blog post on New York’s housing affordability crisis by Sam Stein in The Architect’s Newspaper, which cites my work and motivates me to write this blog post. Regarding the housing affordability problem, he states,

It’s not just the price of housing, it’s the price of land.

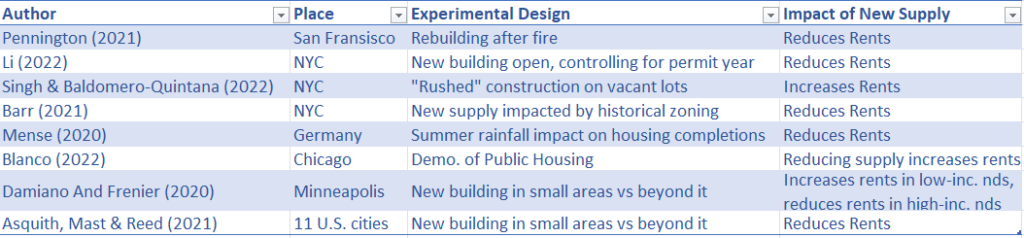

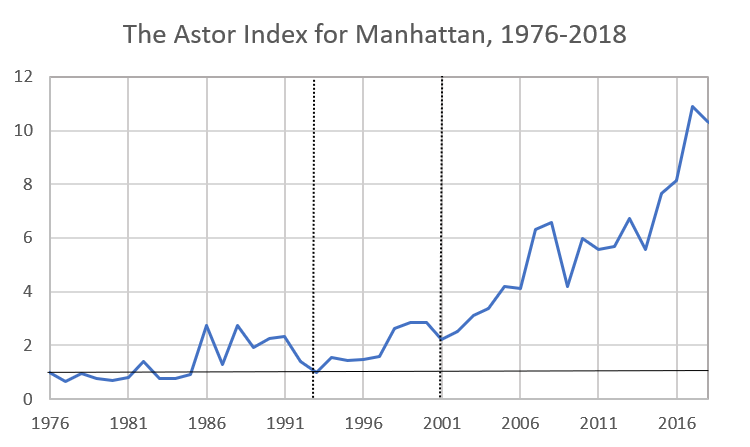

The price of housing is what we all see, but the price of land is a big part of what’s hidden behind it. A 2018 study by Barr, Smith and Kulkarni in the journal Regional Science and Urban Economics found that since 1993, Manhattan’s land values have increased at a compounding annual rate of 15.8 percent, far faster than the rate of job or population growth. By 2014, Manhattan’s land value—separate from the value of anything on top of it—was estimated at $1.74 trillion.

Land Values

But are high land values, in fact, causing the housing affordability problem? The answer is not as straightforward as it might seem. Land is a different type of product—it’s immobile, and its value is determined as much by what’s around it as by anything else.

The substance below the ground provides no actual benefit. Manhattan’s bedrock schist, for example, is nearly valueless. You can’t use it to make countertops or jewelry, and there are no veins of gold. Very rarely, it’s used for building facades—but they are the exception that proves the rule. The soil is not worth much more, either. Brooklyn’s farms no longer produce the cabbages that were made into soups and sour kraut in the Lower East Side.

So, today, the land has only two features of value in the space-time continuum: gravity—you can stand on it—and geography—it has coordinates. Before we blame land for the affordability crisis, we need to understand what drives land values in the first place.

Let’s say a large, choice lot in an urban neighborhood is put up for sale for redevelopment. What would a developer be willing to pay it? Or more broadly, what is the market value of that sliver of the city?

Show Me the Money

Like any asset, the market value of land is determined by the potential net income that it can generate. Would-be developers first perform a series of cost-benefit estimates from erecting various types of buildings at different heights or densities.

A taller building will generate more revenue than a shorter one. But a shorter building is cheaper to build. Even though a taller building might produce more income, the extra cost might reduce the profits. Wealthier people will generate more revenue than those with less income. But they might not be willing to pay to live in a neighborhood far from the center. So, the maximum income might come from those in the middle-income range.

Do You HABU?

After weighing the trade-offs from various hypothetical structures, the developer will determine what’s called the “highest and best use” (HABU)—the height, quality, and expected occupants that will maximize the return from the project. Generally speaking, taller buildings will be erected in the center for higher-income residents and lower-rise buildings will be most profitable as one moves further from the center.

But where do land values fit in? The market price of land—what emerges in the competitive bidding process to take title to the property—is determined after the highest and best use is calculated. In other words, a developer will pay a price for the land such that, once redeveloped, the new building will cover the land and construction costs and provide extra for a satisfactory return on investment.

Society Determines Land Values

So yes, to the developer land is an expense, but one that is essentially determined based on what the developer “should” construct. The marketplace—and, more broadly, society—determines the value of the land. So, fundamentally, high land values are not the driver of housing affordability. Rather, the value of land tells the developer what “should” be done with the lot. And if the land values are high—it suggests that its most profitable use is not affordable housing. Of course, this is galling to many, especially when they see older, charming, or historic buildings being torn down by high-rise condos for the ultra-rich.[1]

Digging Deeper into the Land

However, despite the market determining land values, there is no perfectly free market in land. Instead, land is a highly regulated commodity, limiting what it can be used for. We need to dig a little deeper.

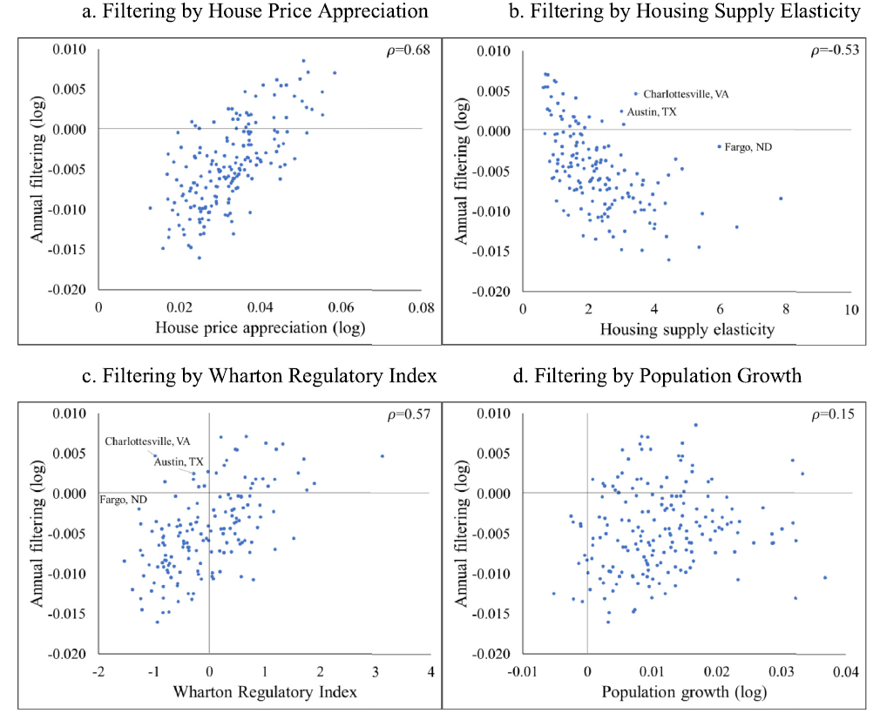

First is zoning. A large body of research shows that overly stringent zoning or land-use regulations will reduce building heights below what the HABU determines. For example, if the most profitable use of a lot is a 20-story tower, the zoning rules require it to rise no more than ten floors, thus lowering the profit from development. If zoning reduces a building to less than its HABU, land values will fall.

Another element is construction costs. The higher they are, the smaller the profit from erecting buildings and thus the lower land values. Big cities like New York and San Francisco are among those with the highest construction costs in the world.

Land valuation methods thus produce a paradox: zoning and higher construction costs, all else equal, reduce land values—and in big cities, which have some of the most stringent and highest costs, we would expect the land value to be lower, not higher. So, what gives?

The Plot Thickens

So far, we’ve been discussing the market for an individual parcel that’s put up for sale. But the solution to the paradox exists by moving up to the wider land market and looking at the total number of lots offered up for redevelopment each year. Here’s where the real problem lies.

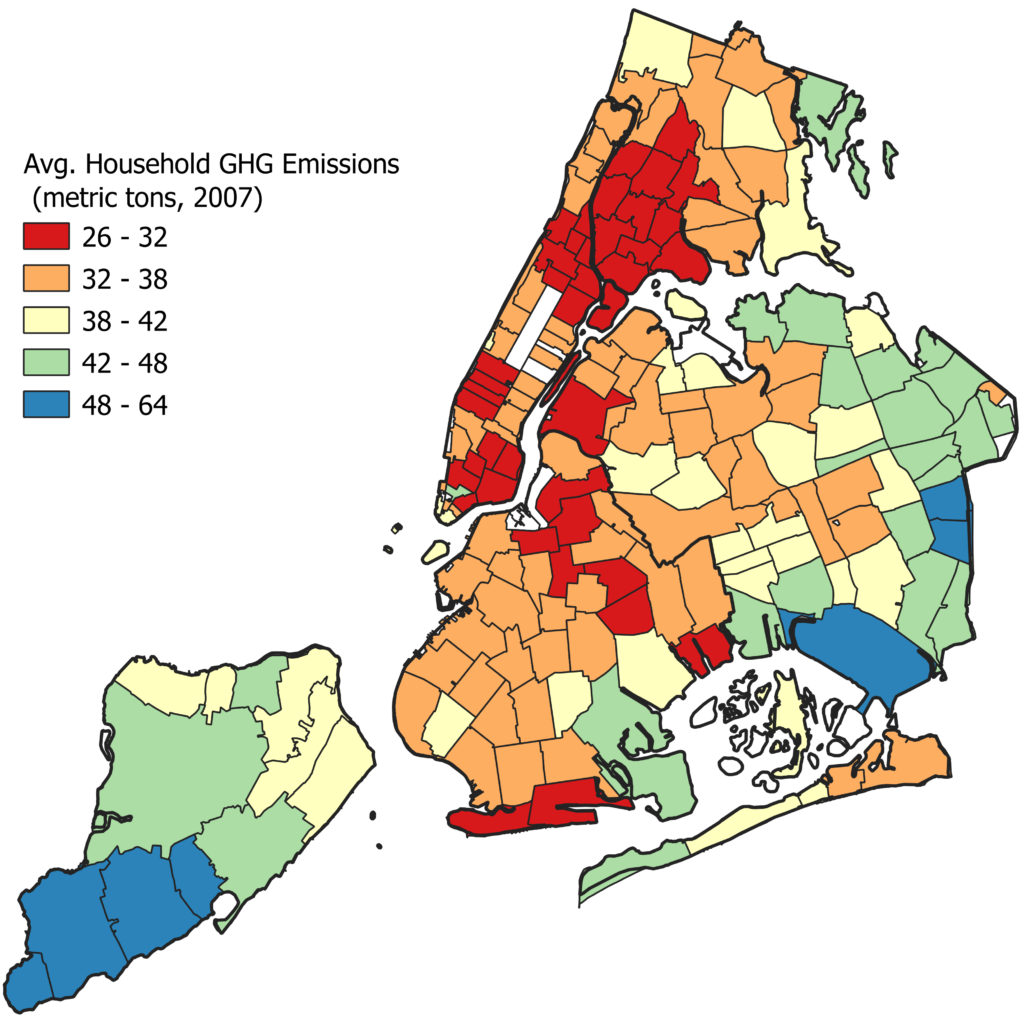

The big takeaway is that government rules, NIMBYism, and other historical barriers to redevelopment create land scarcities, and this land scarcity creates unnaturally high land values, which, in turn, incentives the construction of mostly luxury housing. The demand to live in big cities is so strong, but the number of lots available for redevelopment to accommodate this demand is highly limited. The high land values problem is thus due to the bottleneck in land provided for new housing.

Not the Scarcity You Think

However, I want to be clear about what I mean by land scarcity. New York and other cities are not running out of land—there will always be the land needed to accommodate nearly any population. New York City, however, is placed under an “artificial dome” because its zoning limits its population growth—particularly in the suburban areas. The issue is thus not the total amount of physical land per se but rather the amount made available to accommodate a growing population.

Technological improvements in construction and design mean there’s always the possibility of making more land—in the sky. It’s worth noting that in 1900, a tall building was twenty stories. Today, “tall” is generally considered above 50 stories. And since 2001, nearly 100 residential buildings of 70 stories or taller have been constructed around the world. Brooklyn, for example, just welcomed a new 93-story tower.

Stay or Go?

The way to understand the supply of developable lots that come on the market is to look at the net value of these lots relative to the value of remaining as it is. In other words, we can imagine that every lot in the city has two values—one based on its current use and the other based on its HABU if redeveloped.

We can call the difference between the profits from HABU and its current use the Development Gap. The larger the gap, the more likely a lot will be offered up for redevelopment with more housing units. The point is that the supply of lots is based on the difference in profits from the current use versus the HABU, and as this difference rises, so does the likelihood of redevelopment. In a given year, if many redevelopment lots are offered for sale throughout the city, then in five years, the housing market will be flooded with new units. So, what determines the size of the Development Gap? Let’s review the key elements.

Allowable Floor Area versus Current Floor Area

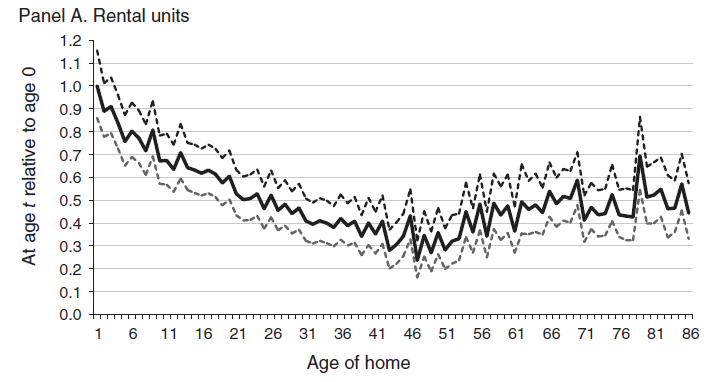

The larger the difference between the building’s current density and allowable density from the zoning rules, the greater the gap and the more likely it will be redeveloped. Conversely, the greater the existing building height or density, the less likely it will be put for redevelopment.

In New York City, for example, 36% of residential lots have their current floor areas at or more than the rules allow. They are essentially undevelopable since building a new structure would have to be smaller than the current one. Nearly 60% of residential lots have floor areas that are either above the allowable amount or within 25%—making redevelopment unlikely.

More broadly, the greater the density of the building, the less likely it will be redeveloped, independent of the zoning rules, due to the high costs of emptying the building, tearing it down, and erecting something more profitable in place. This is a kind of “natural friction” that all cities have to deal with, and it suggests that a critical role of housing policy is to “grease the wheels” to undo the stickiness preventing the construction of more housing. Nimbyists, of course, do not approve of these policies because they reject whole-scale changes to their neighborhoods.[2]

Amount of Land

Even though a well-built city will never run out of land, the total land area does matter. Cities that have more water bodies, more rugged terrain, or steeper hills will be more expensive than those whose surfaces are large, featureless plains. It’s simply a matter of access to more developable lots. These barriers can be overcome with investments in high-speed transport, which can extend the urban area and provide more land for the city.

However, government-created policies can act as a barrier to urban expansion. Some cities create vast greenbelts that reduce developable land. Other metropolitan areas, like New York, create de facto greenbelts because local town zoning ordinances frequently have minimum lot sizes and rules on maximum lot coverage. And they permit apartment buildings in all but a few tiny zones. In essence, suburban communities erect invisible walls that prevent a city from building more housing.

I also want to be clear. I’m not opposed to the region creating large natural woodlands or parks—urban nature is vital. But greenbelts remove land for housing. For example, the Metropolitan Green Belt around London was created to check population density. In 1940, chief New York City planner Rexford Tugwell proposed a greenbelt for New York for a similar reason. However, using greenbelts and other anti-densification measures to stop population growth is antiquated, outdated, and harmful to urban growth and well-being.

Current Income versus Future Income

All else being equal, if redevelopment generates a much higher revenue stream than a building’s current use, it will encourage the parcel to be offered up (assuming the zoning allows it). So much high-rise development takes place in central areas because the income from new construction is so much higher than the income from current buildings, and central-city zoning tends to be much more generous than out in the suburbs. Given the national and international demand for a place in the center, it naturally means a higher gap and, thus, more new construction.

However, there is a large unmet demand for less fancy housing along mass transit lines in the suburbs. Just look at Yonkers, north of the Bronx border, which has big swaths of vacant, formerly industrial land along the Hudson River. It is finally being converted to housing for the “missing middle.”

Rent Controls

Many large cities have some form of rental price controls, which limit rent increases and give tenants the right to stay in their units if they remain in good standing. However, rent stabilization is a double-edged sword, when it comes to redevelopment. When a building is filled with rent-controlled tenants, it reduces the income relative to HABU income and thus incentivizes redevelopment, which are usually market-rate units.

But tenants’ rights to stay also mean that the structure will remain occupied as long as tenants want to stay. Developers can buy out (or, unfortunately, engage in “slumlord” practices) to get tenants to leave, but this will increase the costs and reduce the gap, lowering the likelihood of redevelopment.

Red Tape and Construction Lags

Red tape is one of the most significant problems that reduce the Development Gap. Big cities often place before the developer a big list of boxes they must check and long waiting times before all the permits are given. The delays are even longer when dealing with housing subsidies, novel building designs, or projects requiring a zoning change.

One recent study for Los Angeles looks at permitting times within LA’s Transit-Oriented-Communities (TOC) program, which encourages redevelopment of multifamily housing around transit lines. The authors found that the median time to permit an as-of-right project was 1.18 years and 1.35 years for those requiring additional permissions.

This was just the median time, which means that 50% of the respective projects required longer waiting times for approval—and in a program designed to speed up housing construction. Then consider that at least two to three more years are needed to build out and fill up the building. Before the project begins, at least one year is required to raise funds, design the building, and perform market studies. So, roughly speaking, the project from planning competition for multifamily can take at least four years if things go smoothly—hardly a way to deliver needed housing now.

Property Taxes

If a property’s real estate taxes rise with new construction, the higher costs can provide a redevelopment disincentive. Many cities offer real estate tax abatements to promote new construction. Sam Stein blames residential tax abatements for, ironically enough, harming affordability. He argues that available tax breaks wind up raising the cost of land—because they make redevelopment more profitable—eroding the very benefit they were designed to provide.

But this is not quite true. In a direct sense, the higher price of land is a higher cost, and tax abatements are capitalized into land values. But at the same time, they reduce operating costs for new construction and thereby generate more supply, which can help keep prices in check.

But let’s be clear: Abatements are not causing the affordability problem—higher land values incentivize taller buildings and provide more units. To the extent that abatements also requires set-asides for affordable units, then some go directly to those who need them the most.[3] But if you permanently eliminate tax abatements, you will not solve the housing affordability problem. Yes, land values would decrease, but new construction would not go up unless you released the other frictions preventing redevelopment.

How to Make Housing More Affordable

The simple means to improving affordability is that more lots need to be offered up for redevelopment for buildings with more units, particularly outside the city center where housing demand is local and with more moderate incomes.

Transit-oriented Development

As discussed in other posts, the lowest-hanging fruit is to rezone neighborhoods near transit spots to create transit-oriented development. It seems a no-brainer, yet NIMBYism is preventing planning officials from upzoning these places. A year ago, Mayor Kathy Hochul submitted a plan to upzone neighborhoods near transit stops. It was quickly rejected by the state legislature—particularly those representing suburban neighborhoods. In 2024, she’s going to try again, but let’s see….

Vacancy Targeting

A useful strategy for cities to employ is what I call vacancy targeting. That is, when housing vacancy falls below a low number, say 5%, in a particular neighborhood, the city should—automatically—enact policies that incentivize more construction. This can include targeted construction subsidies and even the building of new public housing (which would be open to a wide range of income groups).

The point is ensure that housing gets built where needed and wanted the most. To make such a strategy work would also require cities to have ready-to-go plans for increasing their local service provisions, such as increasing school capacity and upgrading local parks. If central neighborhoods had higher vacancy rate, voucher programs for the those with low-income would worker better, given the lower competition among renters.

Land Taxes

Today, real estate taxes are based on the value of the structure and the land. If a new building goes up, taxes rise because of the higher value of the structure. However, since land values are the real driver of HABU, and the nature of the neighborhood determines HABU, a more efficient strategy is to tax the land values much higher than the structure value.

A land tax would affect the Development Gap calculus since those with large, underutilized lots would be paying a high tax but with little income to pay for it. They will, therefore, seek to build on the land to create more revenue to pay for the taxes. But land taxes only work if densification is allowed. You can’t turn up the heat by taxing land and then not allow new construction because of stringent zoning.

Furthermore, real estate taxes on the structures should focus on curbing the negative spillovers, or externalities, they create—that is, based on the harm they produce to society. For example, if a new building puts others in a shadow, then the owner should be pay a “shadow tax.” And to the extent that a denser structure will add burdens to the local infrastructure, the developer should pay a development impact fee.

Affordability is Political, Not Economic

At the end of the day, there is no such thing as a city running out of land. Land can be used intensely or sparsely used based on the demand for each location. The supply of lots determines land values across the city—the more supply, the lower the land values, all else equal. Today’s astronomical price of land is due to the fact that too many barriers exist to bring the land up for sale. As a result, current landowners enjoy a “scarcity premium.” When a valuable lot comes up, naturally, the HABU is a luxury condo. So, the high land values are not the cause of the housing affordability problem—they are a symptom that cities are not releasing enough land for needed housing.

What stops officials from allowing the densification is push-back by those who fear new development will harm them in some way. Thus, change requires carrots and sticks to bring people on board. Abundant housing policies would relieve pressure on land prices.

In the next blog post, I will discuss New York City in detail, investigating what is gumming up its ability to provide more parcels for new housing.

—

[1] Now, you might say that developers are strategic—only they know what something is worth because they spend years plotting (no pun intended) and scheming to change the zoning or slowly and quietly assembling small lots. This is true, but the land is not presented to them as a blank slate. The developer can see that certain frictions are holding up a more profitable use and work toward unleashing the value. This developer is engaging in a form of arbitrage, as it were. Additionally, since neighborhood diversity is a key desideratum, housing policies, discussed above, can work to maintain neighborhood diversity–but they can only do so within a context of abundant housing at all locations.

[2] It’s important to recognize that Nimbyism is a form of Prisoner’s Dilemma. From the individual household perspective, to be a Nimbyist is perfectly reasonable and rational. Everyone naturally wants to protect what they have. However, from the point of view of society, preventing neighborhood densification is inefficient and leads to all sorts of social problems, including housing unaffordability, greater wealth inequality, more segregation, and lower economic growth.

[3] For that matter, when the abatements are withdrawn, owners strategically hold onto their lots in anticipation of new abatement being offered. Subsequently selling them without the abatements likely means taking a loss on the investment. Thus, the expiration of the abatements means fewer lots will be offered up until new abatements are enacted.