Jason M. Barr August 13, 2025

Say an apartment building begins to decay visibly, does it increase the likelihood that buildings around it will also decay?

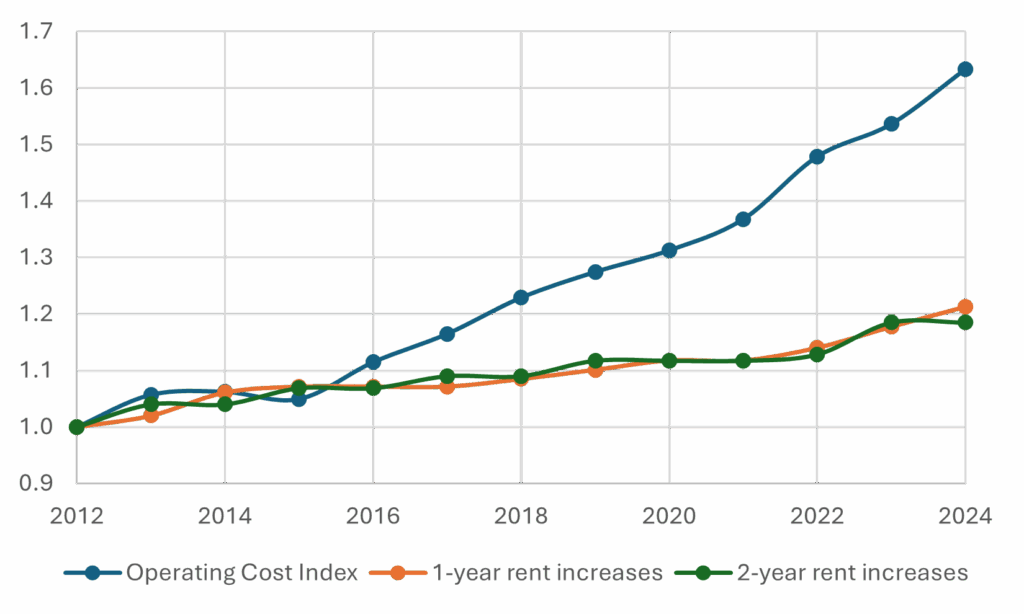

We know that tough economic conditions can impact landlords’ ability to keep their apartment buildings in good working order. As discussed in a previous blog post, there is strong evidence to suggest that New York’s low-income housing stock is slowly decaying due to the combined effect of rapid rises in building operating costs and limits on rents from Rent Stabilization. Building owners, finding their bottom line squeezed, need to reduce non-urgent expenditures to make ends meet.

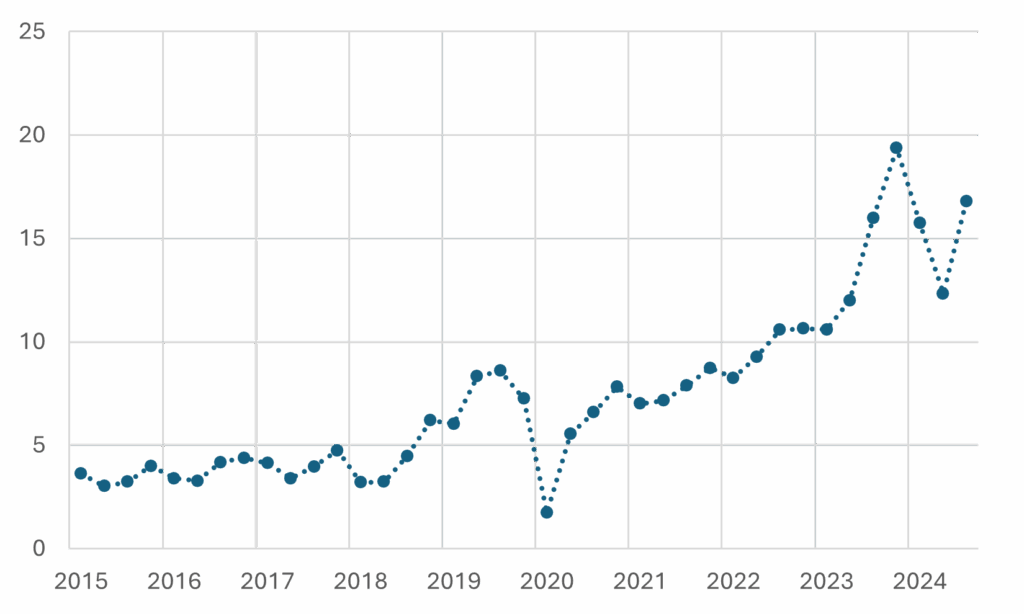

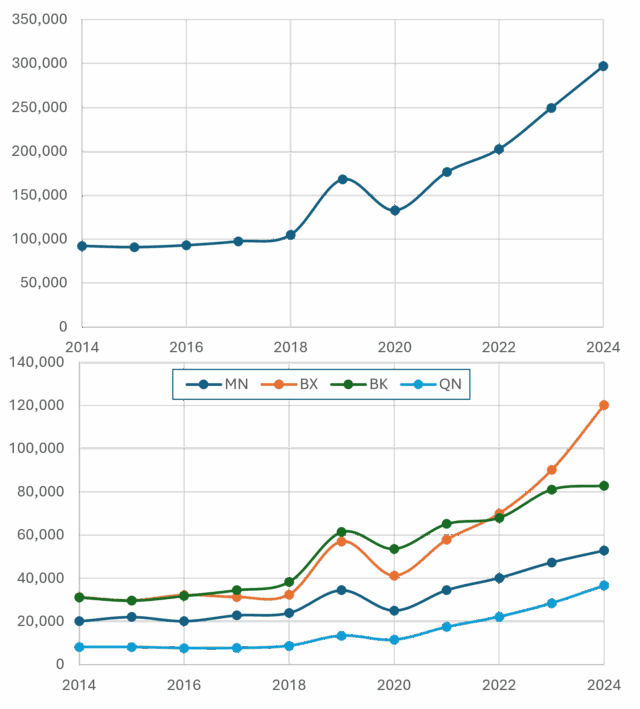

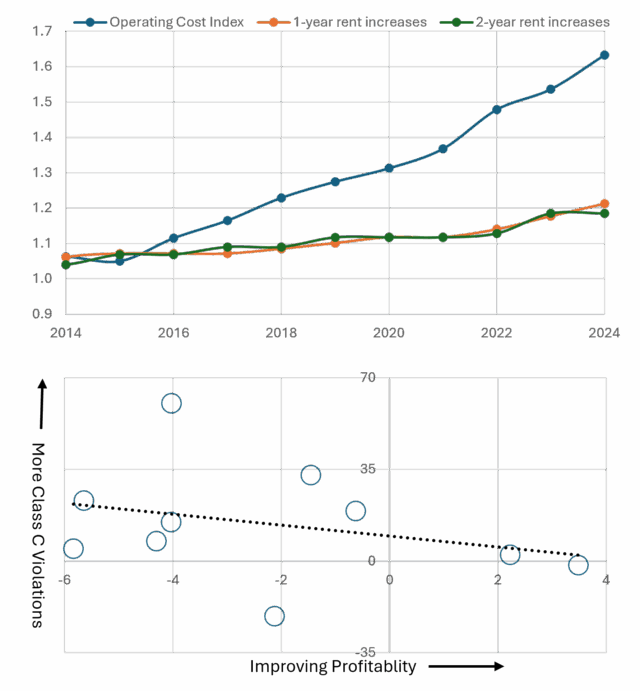

And starting in 2019, the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA) added additional caps to a building’s income. The COVID pandemic compounded the maintenance problem due to supply chain disruptions and labor shortages. However, it’s clear from the statistics (see the figures below) that the economics of operating rent-stabilized buildings have been worsening for about a decade, and with a concomitant rise in building code violations.

More expensive and More Rundown

Testimony in 2022 from two housing advocates illustrates what has been happening to New York’s apartment buildings (with continuing worsening conditions):

The 2021 Housing and Vacancy Survey (HVS) showed a disturbing trend: the city’s housing stock is becoming both more expensive and more rundown. Almost all the markers of maintenance deficiencies tracked by the survey got worse since 2017 (with the exception of heating problems and broken toilets). This could signal landlord disinvestment and neglect, but it could also be a result of the survey’s timing, as building maintenance may have been deferred due to pandemic-related safety and supply chain issues.

24 percent of New York City buildings had rodent infestations in 2021. 18 percent of apartments had leaks, and 17 percent had cracks in their ceilings or floors. Perhaps relatedly, 16 percent need more heat in the winter and 10 percent saw their heat shut off in the winter, which can lead to a dangerous reliance on space heaters or open ovens. 16 percent of buildings with elevators had elevator breakdowns. 9 percent of apartments had mold issues.

But the question remains: Is the decay being exacerbated by a contagion effect across buildings?

Why Contagious?

We must first ask why such an idea is even possible. The answer emerges through the channels of property values and turnover in the types of tenants in the neighborhood. Say a building is under-maintained and its problems are visible and/or known to others. For example, the façade might be in disrepair, or contain graffiti, or garbage might be strewn around the entranceway.

These problems then signal that the building is potentially losing its value, which sets in motion fears of a downward spiral. Banks can become reluctant to loan money to owners in the neighborhood. Without access to funds, investment in the buildings continues to decline.

If residents of adjacent or facing buildings find the building an eyesore (or a source of rats and other vermin), the neighbors might leave. They’ll be replaced with lower-paying households, which means less income to pay for building maintenance or upgrades.

In short, tough economic conditions and/or rent cap policies can lead to under-maintenance. But since under-maintenance generates anxiety among neighbors, lack of upkeep can become contagious, reducing the quality of surrounding properties.

And as each building decays, the cycle amplifies itself, until the neighborhood finds itself in a general state of disrepair, and with more social problems associated with a declining neighborhood, such as rising crime, graffiti, and drug usage.

Abandonment?

If things get so bad and property values can sink low enough, building owners will find that abandoning their properties is better than owning them.

I don’t want to overstate the case. In New York, rental vacancy rates are incredibly low; as a result, few low-income tenants have alternative options. For example, in 2023, the last time rates were measured, citywide rental vacancy was a mere 1.4%, while for units for the lowest income households, the vacancy rate was 0.39% (effectively 0). And building abandonment does not appear to be a problem today.

Nonetheless, even if building owners know they won’t lose their tenants, they are still incentivized to under-maintain their buildings if they see others doing it too. Without any competitive pressures—because of such low vacancy rates—if some building owners don’t keep up their buildings, other owners are likely to follow suit, by the logic that “everyone else is doing it, and besides, I won’t lose my tenants.”

The Evidence

To investigate whether building decay is contagious, I looked at the number of Class C building violations in New York City in 2023 and 2024. The New York Department of Buildings defines a Class C violation as “immediately hazardous” and must be fixed upon inspection. Such violations include peeling lead paint, no hot water, or rodent infestation.

To simplify matters, I investigated the total number of Class C violations in these two years in each census tract (CT) across the five boroughs. However, before we investigate a “contagion effect,” we must first understand the determinants of building violations within census tracts.

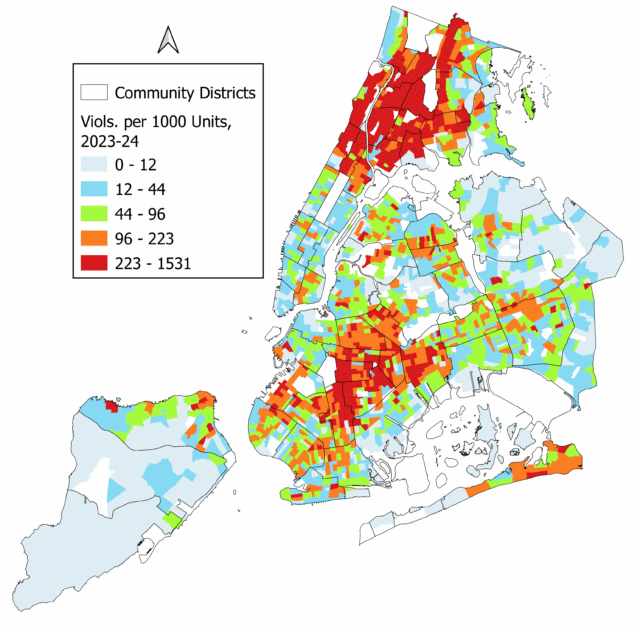

As the map above suggests, the main Class C violation hot spots are in the Bronx, Northern Manhattan, and Central Brooklyn—neighborhoods with low- and moderate-income residents in older low-rise apartment buildings.

The Analysis

I began by performing a statistical (regression) analysis that looks at the factors that drive building violations. (The data sources and tables of results can be found here.)

Historical Violations

The first control variable is the number of violations present in the CT from 2017 to 2018 (before HSTPA). Lower-income neighborhoods with older buildings tend to have more violations, all else equal, and so this original “benchmark” must be accounted for. The results suggest that a CT with 10% more violations in 2017-18 than another one is predicted to have about 8% more violations five to six years later. The good news is that the prediction is less than 10%. Given how severe Class C violations are, the results suggest that city enforcement drives buildings to reduce their relative violations over time, all else equal. Nonetheless, the strong correlation between the past and present suggests that building violations across the city are not random.

Demographics

Next, I added demographic controls for each census tract—the fraction of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher, the median family income, the poverty rate, the population count, and race/ethnicity controls. With these variables, I find the most important predictor of Class C violations is median family income. On average, a 10% rise in the median family income in one CT compared to another will lead to a predicted 2-3% drop in Class C violations, all else equal.

This makes sense. Higher income buildings will have greater rents to pay for upkeep. Since the vacancy rates are higher for these buildings, tenants have more options, which means landlords face greater competition and more pressure to keep their buildings in good working order.

Land Use

Finally, I added in building and neighborhood controls, including the total amount of residential land, a control (dummy variable) for each borough, the distance of the CT to the Empire State Building, the number of residential units in the CT, and the average maximum allowable Floor Area Ratio (FAR) as set by the city.

The results show that Manhattan and Staten Island, all else equal, have the fewest Class C violations relative to the other boroughs, with the Bronx having the highest. Furthermore, tracts with more residential units and that are smaller have relatively more violations.

Taken together, the results show that we can explain a significant fraction of building violations by looking several key variables. All told, income, density, and prior violation counts are the most important predictors.

The Spatial Dimension

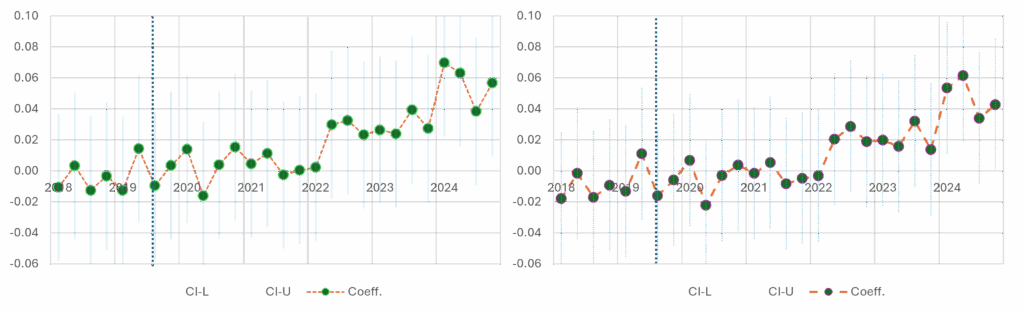

Now that we have a better understanding of the drivers of violations within CTs, we can investigate if, controlling for these factors, there’s also evidence of a contagion effect. To this end, I extended the statistical analysis by performing what’s called, in fancy-schmancy stat-speak, spatial autoregressive models (SAR). This term means that I include measures of the average number of Class C violations surrounding each CT to see if violations in neighboring tracts affect what happens in each respective tract. That is, if one (or more) CTs go on an “under-maintenance bender,” is there an impact on the number of Class C violations in other nearby CTs?

What Happens in a Census Tract…

Based on my statistical analysis, the answer is a hardy “yes”—what happens in a census tract does not stay in a census tract. In short, all else being equal, a 10% increase in average violations of neighboring CT results in about a 0.7% increase in violations within a census tract.[1] While that may not seem like much, recall that in this data set, I only look at one year. If neighboring neighborhoods affect each other, the decay cycle spreads, since each census tract will affect its neighbors in the future. Furthermore, given the severity of Class C violations, the real-life impacts of this contagion effect mean that residents have to live with the added stress and health problems that come from these additional violations.

The larger point is that, as both inflation and housing policy drive a decaying housing stock, the evidence strongly suggests that decline is being exacerbated by the contagious nature of under-maintenance, which adds an additional burden to low-income tenants.

Policy Solutions

Enforcement is clearly a necessity—the more inspections, the faster that violations can be remedied. But enforcement is a reactive measure; it’s only helpful after the problem is brought to the attention of the Department of Buildings (DOB). (One can imagine, too, that many problems are either never reported or exist for some time before being reported.)

There thus remains a strong need for proactive policy responses, in the sense that they increase the incentives for owners to keep their buildings in good working order, thereby reducing complaints to the DOB. The fact that violations have been on the rise over such a long time suggests a much deeper problem than can be solved simply by enforcement. Ultra-low vacancy, combined with restrictions on rents, particularly in a high-inflationary environment, is incentivizing the slow decay of New York’s low-income housing stock.

Highly unaffordable and declining quality is driven by what I call fixed-pie housing policies. Housing construction has been so constrained over the years that the supply cannot keep up with demand. Low-income residents who have access to rent-stabilized units cannot afford to—and are unable to—move if their housing deteriorates. As a result, with nearly 70% of New Yorkers renting their units, leaders do what they can to placate them, at the expense of landlords (and ultimately at the expense of tenants).

More Housing Means Better Quality Housing

The way to keep housing both affordable and in good condition is to create a holistic plan to rapidly add new housing in low-income neighborhoods where it’s needed most. The more competition landlords have, the more they will maintain their properties to attract tenants (or the more likely they are to replace their structures with modern ones, and with more units).

I have outlined policy ideas in other posts, but to summarize what’s needed:

Upzoning

Major upzonings are needed in the outer boroughs, particularly along subway lines. Today 92% of all buildings within one kilometer (0.62 miles) of a subway are three stories or less—and they are fixed at that height by law. If all these low-rise structures doubled their heights (from two to four stories, or three to six, etc.), the housing problem would be solved.[2]

Vacancy Targeting

New York has been in a “Housing Emergency” for eight decades because of its ultra-low vacancy rate. To eliminate the housing emergency and reduce building maintenance problems, the government should target neighborhood vacancies. When they are very low, the City needs to take steps to get housing vacancies above 5%, either through erecting housing itself or through a package of massive upzonings and construction subsidies.

Vacancy Decontrol

As neighborhood vacancies rise, the City can allow for vacancy decontrol. Rent stabilization is needed, it’s argued, because of the housing emergency. As housing vacancy rises through good planning, rent regulations can fall by the wayside without hurting tenants.

Master Planning

Rejection of new housing in neighborhoods is often driven by the fear that this housing (and higher density) will reduce the quality of life. If the government creates a proactive plan to add more schools, parks, social services, and transit access, as new housing comes online, residents will be less likely to take a NIMBY position.

Improved Real Estate Taxation

There are many problems with the city’s real estate tax system. The two most notable are that it’s highly unfair, with low-income renters paying a higher relative rate than homeowners. And, second, tax bills are determined by both the value of the land and the building. Thus, if a landowner redevelops their lot with more units, the building will have a higher tax bill (thus penalizing the provision of more housing). If paired with upzoning, moving to a system that taxes land at a higher rate and structures at a lower rate would help incentivize more housing and would likely benefit lower-income households.

The Future of Gotham’s Low-Income Housing Stock?

The main problem with trying to impose strict rent caps on landlords is that it drives a host of unintended consequences. In this case, limits on rental income push landlords to under-maintain their properties, which then helps to spread further decay via the contagion effect.

The best way to help tenants is not to pit them against building owners. Instead, New York needs to embrace a housing abundance strategy to make sure every neighborhood has ample housing and a greater variety of choices. When this happens, residents will not only pay less for their homes but will also enjoy a higher quality of life and better-maintained buildings.

—

Endnotes

[1] I include a spatial error term in the spatial autoregression. Note, however, that to be conservative, I don’t include the estimate of spatial error term coefficient in the discussion of the “contagion” effect. But given the positive estimate, it suggests that “shocks” to surrounding communities will continue to positively impact the number of Class C violations in each CT. As discussed here, the spatial error model is used as a way to minimize omitted variable bias.

[2] The recent passage of the City of Yes Housing Opportunity is a good start, but much more needs to be done with regard to citywide upzonings.