Jason M. Barr September 10, 2024

Note: This post is part II of an on-going series on the past, present, and future of urban land reclamation around the world. Part I is here.

Cities Drive History

When we study who we are—our ancient histories and how we arrived at the present moment—we tend to study the rise and fall of empires, the lives of powerful leaders, and the struggles to overcome oppression and conquest.

However, behind the curtain, as it were, the engines that drive the grand narratives of history are cities. Cities are stores of knowledge, the nexus of our social interactions, the nodes of trade and commerce, and the seats of power. At the risk of exaggeration, without cities, there would be no History.

The key feature that connects our cities—and binds the world together—is access to water, not just for drinking or crops, but for travel, trade, and defense. Because humans could not fly until very recently, the use of water for transportation has been the connective tissue of civilization and society.

And, arguably, that narrow strip of nature where land and water meet—the littoral zones—are the most important urban zones in human history. They are the transitional spaces from the internal affairs of a people and its state to the external world and the great beyond. Without them, most cities—assuming they could exist—would be isolated urban pockets, nearly cut off from the rest of the world.

From Littoral to Literal

But humans, being builders, are not content to accept the world as it has been presented to them. The need to build and adapt has driven the process of land reclamation—the creation of new land in the littoral zones—and beyond—to foster economic growth and induce social and political interactions.

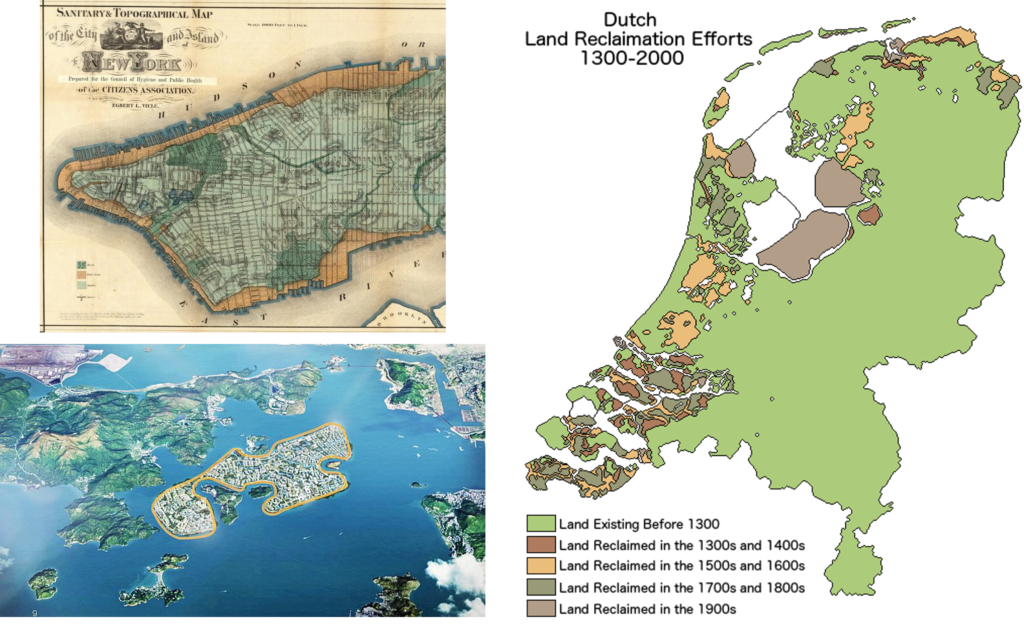

Thanks to recent research using satellite imagery, scholars can measure the ubiquity of land reclamation, which has occurred on six continents, along every ocean, and in every type of habitable climate. Reclamation has been undertaken in the world’s most ancient cities, the important centers of the Middle Ages, and across the globe in the modern era.

The goal here is to give a (necessarily brief) set of examples of how land reclamation is connected to and connects world history to demonstrate that it represents a hidden—both beneath buildings, walls, piers, tarmacs, and parks, and understudied—element of larger global events. Of course, we can’t provide the counterfactual of how world history would have unfolded without reclamation, but we can get hints of its role.

The critical point is that land is far from being a finite resource; producing more of it has allowed cities to grow and accommodate people, buildings, and commerce, which enabled their dramatic parts in world history. Let’s begin our world tour with a focus on the pre-industrial past. In a future post, we will turn to the modern period.

Tyre

In the tenth century BCE, Hiram, the Phoenician king of Tyre (in Lebanon) decided to move his city on the eastern Mediterranean coast to a site about 2,000 feet (600 m) offshore where two flat, partly-submerged rocky islands provided foundations for one of the great metropolises of the ancient world. Rubble and boulders were transported from the mainland to infill the channel that separated the two islands, likely taking thousands of workers and years to complete. The new home for Tyre produced a defensive advantage and excellent harbors which the seafaring Phoenicians used to gain wealth from trade.

Furthermore, as reclamation historian Brian Hudson reports,

As in many cases, where security considerations encouraged the foundation of settlements in naturally defensible locations, the pressures of Tyre’s urban growth caused serious development problems on the confined insular site. The Phoenician city’s response to this was much like that of modern New York or Hong Kong: it built upwards in the form of high density multi-story buildings, it expanded into the sea by reclamation, and it probably overspilled onto the mainland.

Tyre eventually fell to a siege by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, when his army built a causeway from the mainland and stormed the city.

Carthage

About a century and a half after Hiram’s rule, a group of Phoenicians left Tyre to found the city of Carthage, or “New City” in their Punic language, on the North African coast of the Mediterranean Sea (in Tunisia). Carthage became one of the most important trading hubs of the ancient world. By the fourth century BCE, it was the center of an empire that ran along the North African coast, into eastern Spain, parts of Sicily, and several islands in the Mediterranean.

While precise details of Carthage’s layout remain murky, archaeological evidence suggests that the Carthaginians undertook vast land reclamations to create a thriving port. Historians Henry Hurst and Lawrence Stage write,

The two harbours were man-made landscape on impressive scale. From the flat former marshland an estimated 120,000 m3 (156,954 yards3) of earth had been excavated to make the rectangular harbour…and a further estimated 115,000 m3 (150,414 yards3) had been removed to make the circular harbour … most of this soil was dug from below the contemporary sea level. An estimated 10,000 m3 (13,080 yards3) of soil had been deposited on the Ilot de l’Amirauté [a circular island within the circular port] to give this the conical shape required for the slipways of the naval shipsheds; and a similar effort must have gone into making the ramps for the shipsheds at the harbour’s edge.

While Carthage was the dominant power in the southern Mediterranean, Rome emerged as a rival, which led to a series of wars known as the Punic Wars (264-146 BCE). The most famous character to appear during this period was the Carthaginian general Hannibal, who led his army on land from Carthage up through Spain and down through the Alps in 218 BCE to meet—and beat—the Romans on their territory. Though Hannibal’s military success was legendary, the ultimate defeat of Carthage allowed for the ascendancy of Rome (which also used reclamation to promote agriculture in its hinterland).

Constantinople

In 27 BCE, the Roman Republic gave way to the Principate, with the rise of Caesar Augustus as the first Roman emperor, and from whom would follow a long succession of emperors. In 286 CE, the vast territory, running from Spain to Syria, was divided into two administrative zones of east and west, each to be ruled by a co-emperor (and their respective junior caesars). However, clashes between the rulers frequently led to civil war.

After one such war, the Roman general Constantine became the Western emperor in 312. He eventually united both halves under his rule in 324. During this period, Constantine converted to Christianity. While it would not become the official state religion until 380, the Christian Church was now ascendant and integrated with the state. Constantine created the city of Constantinople (Istanbul) to be his center of power. After the Western half of the empire collapsed in the fifth century, Constantinople continued as the capital of the Roman (or Byzantine) Empire until 1453.

Constantinople’s growth and success was due, in part, to land reclamation. Writing in the year 1923, historian John Bagnell Bury records that,

Constantine was more successful perhaps than he had hoped in attracting inhabitants to his eastern capital. Constantinople was dedicated in A.D. 330 (May 11), and in the lifetime of two generations the population had far outgrown the limits of the town as he had designed it. The need for space was partly met by the temporary expedient of filling up the sea, here and there, close to the shore, and a suburban town was growing up outside the Constantinian wall.

But, as Brian Hudson argues, “[Bury] was wrong, however, in describing the reclamation of littoral areas on the fringes the city as ‘a temporary expedient,’ for its land area continued to be enlarged in this way over the following seventeen centuries.

The Commercial Revolution

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, power across Europe became decentralized, with a patchwork of primarily Germanic kings and princes ruling their lands, though the Catholic Church remained the one unifying force. However, in parallel to the feudal society was the rise of autonomous trading cities, which helped foster the Renaissance, the Commercial Revolution, and Europe’s period of conquest and colonization.

Two of the most successful and influential cities were Venice and Amsterdam, both of which were run by merchants seeking profit from international trade, and both owned their existence to land reclamation. The merchants created financial innovations that allowed for easier access to capital and to reduce the risks from long-distance shipping and commerce.

Venetian bankers, for example, initiated the market for government securities, which financiers copied in Pisa, Verona, Genoa, and Florence. The ability to sell government securities meant lower risk and a broader market, creating a larger pool of funds. The Dutch invented the joint stock company, which allowed shareholders to invest in businesses to earn a share of the profits, while reducing their exposure. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company issued the first shares on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, and one of the first companies in world history to be formed as a joint stock company.

Venice

Venice was founded in the fifth century on a marshy lagoon just off the mainland, where its location afforded protection from invaders. The city originated from a group of 19 islands (Rivo Alto (Rialto) Islands) located the lagoon. Their initial area added up to 0.4 square miles (1 km2). In the 12th century, Venice was expanded through reclamation until it reached close to its present 2.7 square miles (7 km2).

The original settlers learned to build by driving closely spaced tree trunk piles into the mud and sand, until they reached a harder layer of compressed clay. Building foundations rested on plates placed on top of the piles. As Hudson writes, “To build a capital worth of the emerging Venetian Republic, it was necessary to stabilize, drain and enlarge by reclamation the low-lying muddy island of the Rialto and to improve the sea defenses of the Lagoon…. Material excavated from the canals was used to raise ground levels….”

By the High Middle Ages, Venice was a flourishing trade center between Western Europe and the rest of the world, especially with the Byzantine Empire. After Constantinople’s fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Venice began to decline.

Marco Polo

As a side note, Venice was the birthplace of Marco Polo, whose famous narrative recounts the story of his journey from Constantinople to China and his return to Venice. His tales inspired countless European explorers seeking access to the East’s riches. By the 14th century, this became increasingly possible as nation-states like Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands began to finance and promote sea-going voyages. Venice’s rival, Genoa, gave birth to Christopher Columbus, who, in 1492, appealed to the king and queen of a newly formed Spanish kingdom to sail west for Crown, coin, and Christianity. Marco Polo’s adventures inspired Columbus.

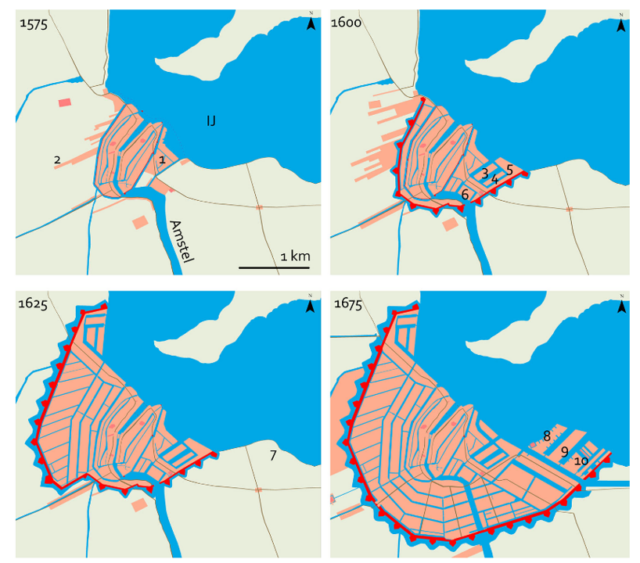

Amsterdam

In the 16th century, the Netherlands rose to great heights as a Western power. Unlike, the monarchies of Spain, France, or the United Kingdom, the Netherlands was a republic of united city-states. The most important Dutch was Amsterdam, whose history was greatly influenced by the rise of the Spanish Empire, which emerged after Columbus’s voyages led to its conquests from Mexico to Chile.

Amsterdam’s success came, in part, from its vast reclamation efforts. As the archaeologist R. M. Jayasena writes,

Amsterdam began developing about c. 1175 where the mouth of the Amstel River empties into the IJ, an elongated waterway leading to the Zuiderzee, the former interior body of water that connects to the North Sea. The settlement started along dikes on the Amstel, which were connected by a dam in the third quarter of the 13th century. The first half of the 14th century saw the beginning of the process of land reclamation in the floodplain of the river Amstel. Sods of clayey and peaty earth were deposited on the riverbanks and over time the riverbed was reduced in width from c. 170 to 90 m. By about 1500, land reclamation in the river and the IJ, along with largescale landfill behind the dikes, had resulted in an urban area of c. 80 hectares, or roughly 198 acres.

However, the Protestant Dutch revolt against the expansionary Catholic Spanish monarchy, starting in 1568, triggered a turning point for Amsterdam. When the Spanish forces captured Antwerp, refugees flooded into the northern Netherlands, particularly into Amsterdam. The influx of new residents, along with its economic growth, promoted it to expand the city’s footprint. Starting in 1585, municipal leaders initiated large-scale reclamation extensions, which gave rise to its rings of famous canals. The period from 1588 to 1672 is known as the Dutch Golden Age, where trade, science, art, and influence flourished.

The Dutch’s rivalry with Spain also led them to form the Dutch West India Company, which founded New Amsterdam in 1624. Upon arrival, the settlers began draining the wetlands and creating canals like those back home. Little did the Dutch know it then, but they were laying the seeds for one of the world’s greatest metropolises.

The Aztec Empire

While European nations were emerging from their feudal period, the Aztec Empire arose in the Western Hemisphere, with its capital city of Tenochtitlán, now the historic center of Mexico City. It was founded ca. 1325 among a group of islands in the marshes of Lake Texcoco, in a reclamation process echoing that of Venice.

Over the next two centuries after its founding, the city expanded in the lake into a gridded network of canals and raised earthworks and spread out to nearly four square miles. As Hudson writes, “Together with the suburbs which stretched along the shore of the lake, this pre-Columbian Meso-American conurbation housed a population of over one a million.”

Worlds would collide in 1519, and global history, once again, would take a turn, with the arrival of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and 400 soldiers. As the journalist Roger Atword records, Cortés found that the

streets were so crowded that the Spaniards could barely fit through them. And the hubbub of the main plaza, full of shouting salesmen offering everything from beans to furniture to live deer, could be heard miles away. “Among us there were soldiers who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople and all of Italy and Rome,” wrote [chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo]. “Never had they seen a square that compared so well, so orderly and wide, and so full of people, as that one.

The invasion of Tenochtitlán initiated the fall of the Aztec Empire, the rise of Spanish imperial control, and eventually led to the formation of modern Mexico, which achieved its independence in 1810.

The British Empire

While the Spanish and Portuguese were conquering, colonizing, and commercing in the 16th century, Britain remained a small nation ruled by the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I (1533-1603). During her reign, she permitted the voyages of merchant adventurers, such as Walter Raleigh, who sailed to North America in 1564. The Commercial Revolution eventually reached London, where bankers started financing the Crown’s wars and merchants and “pilgrims” trips abroad. (Over the centuries, reclamation of the banks of the Thames allowed London to become a global port.)

Mumbai

In 1600, London merchants created the British East India Company (EIC) to muscle in on the Dutch and Portuguese in Southeast Asia. In 1661, the British took control of the Portuguese-held territory of Bombay (Mumbai), and in 1668, it was transferred to the EIC.

Bombay consisted of a ring of islands in a harbor on the west coast of India. The number of distinct islands was open to interpretation since large areas were underwater at high tide and during the monsoon season. At other times, it was possible to cross between the islands on foot. Starting in 1709, the EIC began reclaiming the land between the islands to eventually form one large peninsula.

However, as historian Tim Riding records,

In most respects the reclamation was a failure. Between 1737 and 1781 the company made around 94,000 rupees in revenues from paddy fields in the recovered area, an insignificant amount that was far smaller than the costs of reclamation….The reclamation failed to meet Bombay’s food requirements, which only grew as the town started to expand. The EIC generally saw the project as a costly mistake, writing that they would never have consented to the work if they had known the true costs.

Nonetheless, the newly developed Bombay would emerge as a vital port and trading city within the British Empire. From the port, the British would export vast quantities of opium to mainland China, which generated anger and resentment by Chinese imperial officials, and which led in 1839 to the First Opium War, with profound implications for world history.

During the war, the British seized the island of Hong Kong in 1841 and thus began its history of what is today the world’s densest skyscraper city (and which undertook vast land reclamations). And just as importantly, the war led to the opening of so-called Treaty Ports in China, such as Shanghai, where Europeans established neighborhoods from which they could engage in the China trade. Shanghai’s Bund, along the Huangpu River, reclaimed and rationalized over the years, became the center of British and French interests.

But to the Chinese, the Bund was a sore of Western imperialism. Anger against the European presence helped fuel the Communist Revolution and the rise to power of Mao Zedong in 1949.

The United States

While we will have more to say in a future post about reclamation in the United States, we can end with an important note for world history. When the British were conquering and trading in the Far East, they also, of course, created settlements in North America, running from Georgia to New England.

However, they were not content to permit the Dutch their colony along the Hudson River. As a result, in 1664, the English sent four warships to New Amsterdam. The colonial Governor, Peter Stuyvesant, quickly realized he was in no position to resist and surrendered.

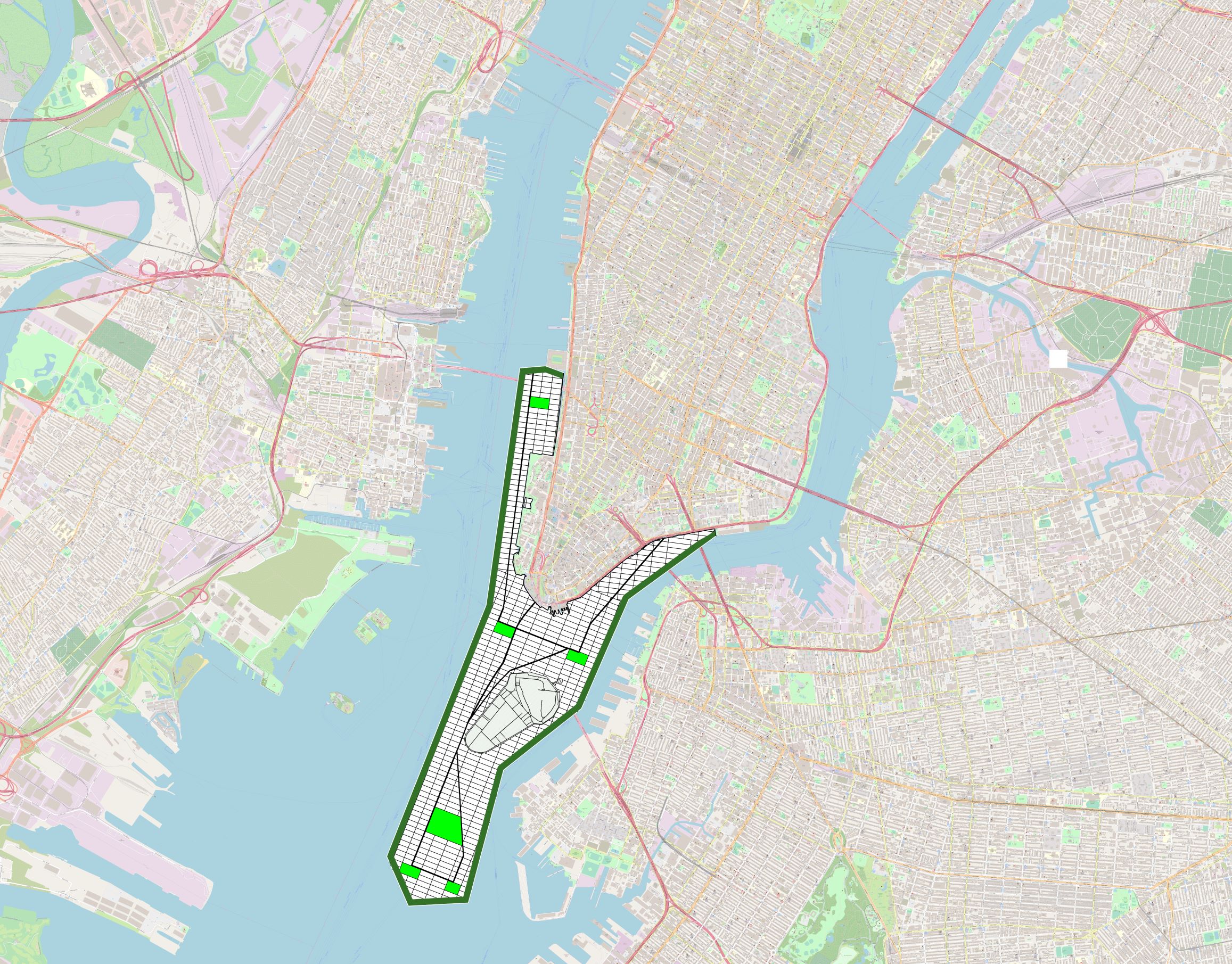

Thanks to this victory, New York went on to become one the world’s most important cities due, in part, to its expansion of Lower Manhattan through reclamation. In the early 20th century, Lady Liberty would welcome my ancestors among the “teeming masses yearning to breathe free,” who arrived at the (reclaimed) Ellis Island, eventually leading to my writing this piece on the global history of land reclamation.

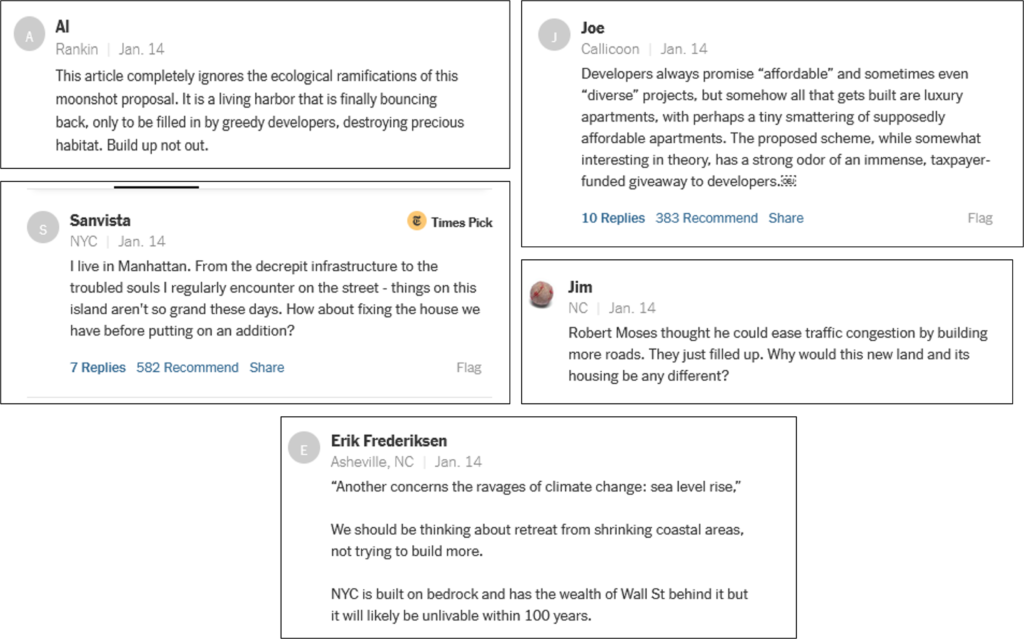

Continue reading: Part I of this series on land reclamation is here and my post on my proposal to expand lower Manhattan is here.