By Jason M. Barr October 20, 2017

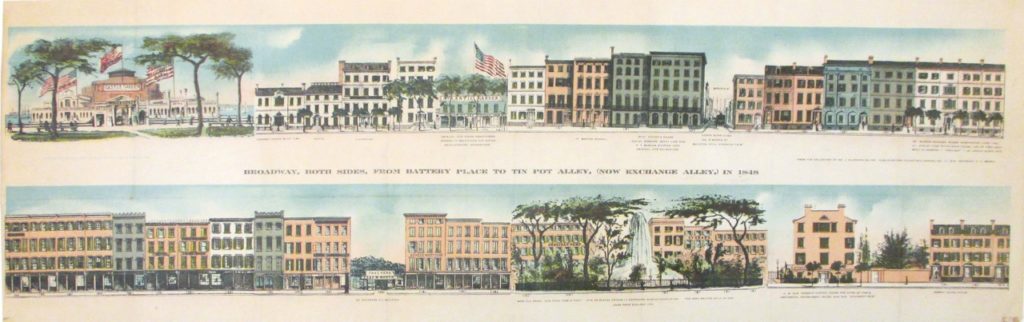

In the year 1848, a stroll down lower Broadway in Manhattan would have revealed a decidedly low-rise town. The reason was simple: the only way to get to the top floor was to climb the stairs. Humans, unlike birds, do not have the anatomy to defy gravity (what would offices for birds look like anyway?). As a result, property owners had no incentive to build taller, since few would pay to be on higher floors.

If, for your whole life, five-story buildings were the tallest you knew, save for church spires or bell towers, imagine how shocked you would be when eight-, nine-, and ten-story buildings started to emerge. They would truly appear to scrape the sky.

As discussed in a previous post, after the Civil War, buildings started to grow taller, due to both economic demand and new technology. By 1890, the Skyscraper Revolution was in full swing in that the key technological barriers to building tall had been broken. No longer did church and state have a monopoly on building height, but now it could also be provisioned by the private sector. By 1900, 25- to 30-story tall buildings started to appear; and by 1908, 47 stories was Q.E.D. when the Singer Building was completed in New York. Today, lower Broadway is known as the canyon of heroes.

A key point is that when building height finally became a variable in the real estate equation, it opened up possibilities for developers to choose different heights based on their own motivations and access to financial resources. When this happened, things began to get interesting because humans need to express themselves, and the tall building, after say 1890, became a great means of expression. Pioneering skyscraper architect, Louis Sullivan, promoted this idea in 1896, when he wrote:

What is the chief characteristic of the tall office building? And at once we answer, it is lofty. This loftiness is to the artist-nature its thrilling aspect. It is the very open organ-tone in its appeal. It must be in turn the dominant chord in his expression of it, the true excitant of his imagination. It must be tall, every inch of it tall. The force and power of altitude must be in it the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line….

As I will discuss in another post, we can understand the building height choices of developers as some function of economics (the financial costs and benefits of building) and the symbolic component (advertising and height competition), and which, fundamentally, spring from urbanization, population and economic growth, and globalization.

These forces have driven skyscrapers to grow taller over the 20th century. Before World War II, there were pronounced height cycles in that height would rise and fall, on average, with the business cycle. However, after the War, there has been a steady uptick in the average heights of the tallest completed buildings (though they are not immune to business cycles).

In the 1950s, the tallest buildings were typically above 175 meters (45 stories), by the 1990s, buildings greater than 300 meters (65 stories) were common. In the last 10 years, 500 meters (100 stories) is the new benchmark for tall. This evolution can be seen in the figure below, which shows the height of the tallest building completed each year around the world. The Council on Tall Buildings (CTBUH), the de facto arbiter of building height, provides definitions for the various forms of tall:

A “supertall” is a tall building over 300 meters (984 feet) in height, and a “megatall” is a tall building over 600 meters (1,968 feet) in height. As of today, there are 125 supertalls and only 3 megatalls completed globally.

Horse-Racing Height

When looking at a megatall structure like the Burj Kalifa (828 meters, 2010) one can’t help but think it’s a monstrous giant—a “freak project.” But is this true?

The answer is both “yes” and “no.” Yes, in that the Burj is much taller than the next tallest building by 319 meters. But ‘no’ in the sense that its height represents a logical progression since 1890.

Consider a “horse race” thought experiment. Imagine it is January 1, 1900; you had $119 to invest. At the same time, you see the world’s tallest building is 119 meters (the Park Row Building in New York City). If you had invested that $119 how much would it have been worth by say January 1, 2017? Comparatively, how tall would be the world’s tallest building? Who would have won the race?

Further, let’s say you have two options for your money. First is that you can “invest” in the American economy. That is, how much is your $119 worth today in terms of national income (Gross Domestic Product)? Or, if you can invest $119 in the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) stock index. How much would you have today?

After adjusting for inflation, $119 worth of GDP in 1900 has grown to about $4464. In other words, the American economy has grown by a factor of 37.5 since 1900. This gives an average annual growth rate of about 3.1%.

The inflation-adjusted value of the S&P index would have increased in value to $1,453, a factor of 12.2, or an annual average rate of about 2.7%; assuming no reinvestment of dividends.

Growth of the world’s tallest building comes in third, going from 119 meters to 828 meters, a factor of just shy of seven, or an average annual growth rate 1.67%.

This comparison only uses the U.S. economy; we could have measured the growth rate of the fastest growing economies in the world, in which case the comparison would favor economic growth over skyscraper growth even more.

Starting in the 1990s, skyscraper construction has been, for the most part, an Asian phenomenon, with China and the Arabian countries taking the lead. These countries have seen growth rates far above the U.S.

In this horse race—the world’s tallest building versus the U.S. economy—one can’t help but ask, not why are skyscrapers so tall, but rather why aren’t they even taller? We will return to this question in future posts.