Jason M. Barr August 31, 2022

New York City suffers from a housing affordability crisis.

The fundamental problem is that there are too few homes to keep up with the demand, particularly in the middle- and lower-income areas. The rich get the units they want because their money incentivizes developers to provide them. Besides, the places where global jetting setters have apartments are where zoning regulations are the most generous, mainly because of Manhattan’s long history of welcoming density.

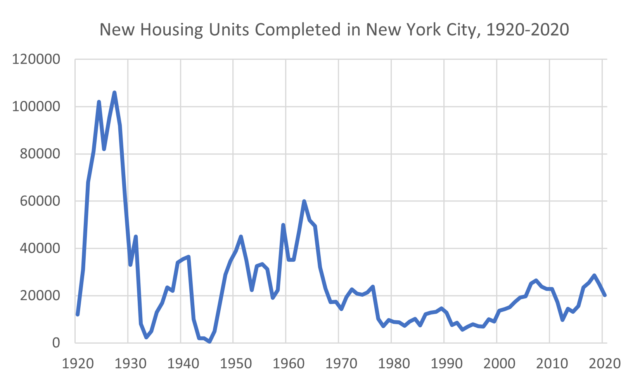

A Century of New Housing

A review of new housing over the last century shows that new construction across Gotham in the 21st century has been underwhelming compared to past decades. The last era of big supply increases ended circa 1965. The Roaring Twenties was the best period, where the city was averaged close to 100,000 new units per year. 85% of Gotham’s housing was built before 1975.

Since 2010, just 11% of the roughly 2,100 census tracts in New York City have provided 80% of its new housing units; most of these tracts are close to the city center. In other words, only a few census tracts are doing most of the “heavy lifting.” Hardly a way to end an affordability crisis.

Let’s say that each census tract “pledged” to add its fair share of housing by increasing the number of units by 10% over the next five years—through new construction, conversions, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), etc.—that would add 365,000 units, more than what has been added to the city in the last 15 years (see the figure below). This kind of fairness would be a huge boost to affordability.

In this blog series, I aim to uncover the nature of the frictions to new housing in places where high-rollers are not interested in putting their money—the places where housing is desperately needed but is not being supplied.

Norwood, The Bronx

In a previous post, I looked at the Norwood section of the Bronx. By many measures, it is a successful dense working-class neighborhood with excellent parks, easy access to public transportation, and a strong retail corridor. Yet, a review of the housing stock shows that the neighborhood is frozen in time, with 95% of its residential structures built before 1965! This is a waste, given that Norwood has all the attributes for more transit-oriented housing.

So, what are the main frictions? First is the costs of new construction relative to the residents’ income. Because it is a working-class neighborhood (far off the gentrification path), the income that households can pay for housing is quite limited. The median household income of Norwood is $40,000. Using 30% of gross household income as a benchmark would suggest that the typical household should pay less about $1,000 monthly for rent (the actual median rent is $1,600).

But because of its current density, land values are relatively high, coming in at around $430 per square foot of land. This, combined with the fact that average construction costs for a new apartment building run around $300 per square foot, means that the return on investment on new construction would not generate a sufficient return to attract redevelopment. From an investment perspective, buying an existing apartment building is more profitable than building a new one.

More Frictions

But say the construction costs were lowered, for example, through generous subsidies or reductions in the costs of labor, materials, or building methods, this would not solve the problem. In Norwood, there is a “land shortage.” Most apartment buildings have rent-stabilized tenants. As a result, it’s nearly impossible to empty an old building to tear down. Given the construction economics, a developer would likely need to combine two or more lots and have the tenants in both buildings leave voluntarily, a near impossible task.

A large part of the reason they don’t want to leave is that vacancy in the neighborhood is so low, thanks in large part to rent stabilization and the lack of new construction. Where would they go if they left? Rent stabilization creates a Catch-22—tenants can’t leave because there is nowhere to go, but there is nowhere to go because tenants don’t leave. The rental vacancy rate in the Bronx is now 0.78%!

But let’s say the government came up with a plan to facilitate the movement of people to other buildings nearby, you still would not have solved the problem, because of the zoning regulations. In Norwood, nearly all the residential properties today are required—by law—to be five stories or less. There is no way a developer could buy a low-rise building and construct, say, a 10- or 12-story one in its place (with twice as many units). The rules forbid it.

With all these frictions, is it any wonder that no new housing has been provided in decades?

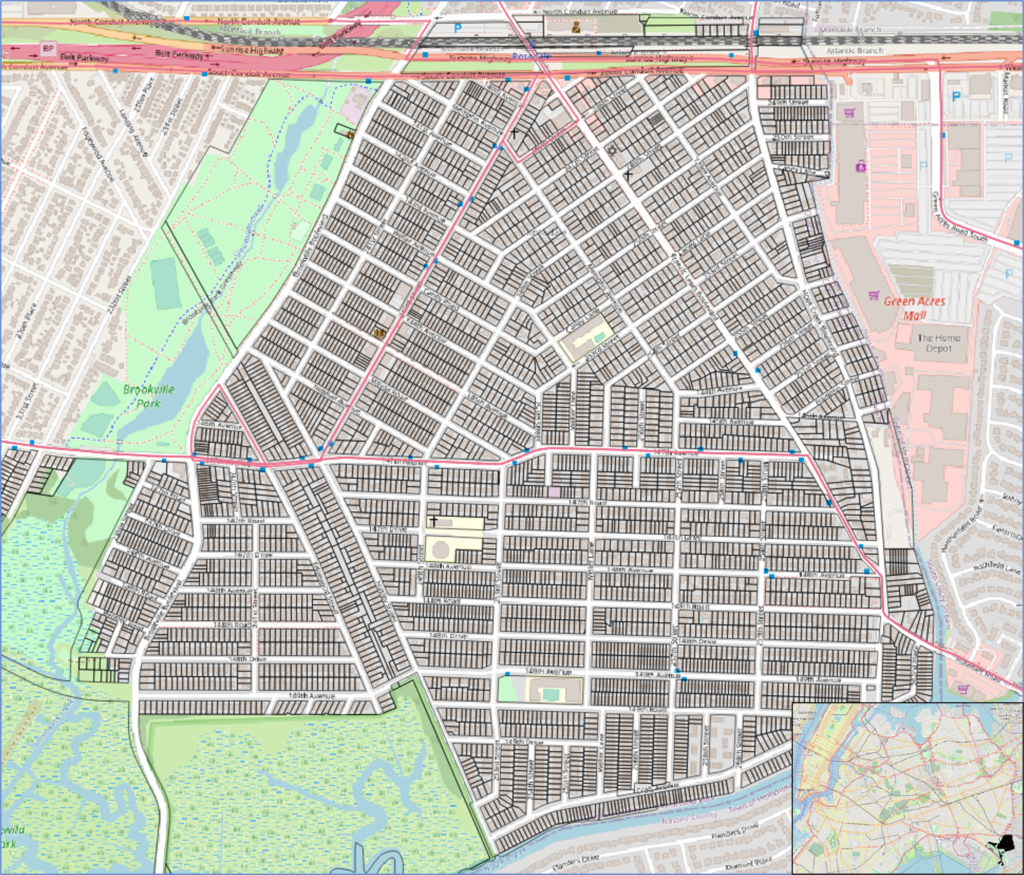

Rosedale, Queens

But Norwood is just one type of neighborhood. New York is nothing if not a city of neighborhoods. To explore the kinds of friction in a suburban community, comprised mostly of one- and two-family homes, we can look at the Rosedale section in Queens. This is a very different place than Norwood. Rosedale is literally at the edge of the city, sharing a border with Nassau County, one of the world’s largest bedroom communities. The median household income, about $93,000, is over twice as high as Norwood.

The neighborhood has about 25,000 residents covering 2.1 square miles (5.4 km2), with a density of 19 people per acre (compared to 120 people per acre for Norwood). About 80% of its residents are Black or African American, with 9% Hispanic and 5% White.

Amenities

The neighborhood has a suite of local amenities. The 90-acre (36 ha) Brookville Park is on the western border. The Long Island Railroad (LIRR) stops at the northern edge. Because it is a small neighborhood, most residents can walk to the station. The rail line runs parallel to Sunrise Highway, a six-lane “highway” with traffic lights. The Greenacres Mall is just on the Nassau side of the border, and JFK Airport is also a stone’s throw away.[1] The southern part of the neighborhood is bordered by a deep channel, onto which backyards abut. Several houses have docks for personal boats.

There’s plenty to offer, but, by my estimate, it has barely grown its housing stock. In 2002, there were about 6,210 units, and in 2021, that figure was close to 6,850—a 10% growth in two decades, an annual rate of about 0.05%. Nearly 90% of properties are one- and two-family homes (and about 5% are apartment buildings). Nearly half of the homes are for two or three families, suggesting a relatively high demand for rental units.

The median price of a one-family home is $610,000. This puts the house price-to-income ratio at about six—considered double the “affordable threshold” of three. In this sense, the typical middle-class household in Rosedale also suffers from an affordability problem.

The Economics of Redevelopment

Since Rosedale is a middle-class neighborhood of free-standing homes, the problem of redevelopment is not rent stabilization. So, what are the frictions?

To see, we need to investigate if it’s economically feasible for property owners to densify. What is the “optimal” density given the income and costs of construction and land? If the optimal density is greater than the current density, it suggests, in this case, that the key friction is either zoning or land assembly.

To this end, I “costed out” various types of redevelopments on the assumption that a developer would buy two typical adjacent lots of 4,000 square feet and combine them to make one relatively large lot (in Manhattan, nearly all the residential lots of this size have 5- or 6-story apartment buildings). I looked at both rental buildings and condominiums (the data, assumptions, and analysis can be found here).

The results suggest that from an economic point of view, the neighborhood has too few housing units. Rosedale has the demand to support garden apartments and low-rise multifamily buildings. That is to say, the revenues from new construction would more than pay for the costs. My analysis also shows that condos would be more profitable than rentals.

The Zoning

Seeing how the neighborhood “wants” more housing, why can’t it get it? A look at the zoning regulations gives some clues. All the residential buildings fall into an “R3” district, with 60% as “R3X.”

R3X

With the R3X regulations, no structure is legally allowed to have a floor area ratio (FAR) greater than 0.5. This means for a typical 4,000 square foot lot (372 m2), there can be no more than 2,000 square feet (186 m2) of space. In addition, there is a height limit of 35 feet (11 m). The house must be set back at least 10 feet (3 m) from the street, and the rear of the home must be at least 30 feet (9 m) from the property line.

In addition, R3X has “contextual zoning” rules which require pitched roofs after 21 feet (6.4 m), further restricting the flexibility of construction.[2] At least one spot of off-street parking is required per dwelling unit.

While the other R3 districts—in this case, R3-1, R3-2, and R3A—have slightly different rules, the broad parameters are the same. No residential structure in Rosedale can have a FAR greater than 0.5, nor can it rise more than 35 feet (11 m), and it must provide off-street parking.

All these regulations mean that it’s illegal to have anything more than a one- or two-family house. In short, nearly 90% of the neighborhood property owners must keep their homes exactly the way they are. More than half of the structures are over the allowable floor area ratio, and nearly all the rest are so close as to make it economically unfeasible to tear them down and replace them with anything except a ballooned-up, more modern version of what’s there now.

The neighborhood is mandated by law to be frozen in time.

Zoning as Blunt Instrument

What’s even more perverse is that amenities surround the neighborhood. The LIRR station is within walking distance (or is a short bike or bus ride away). The western part is bordered by a park, and the eastern part is next to a mall.

The zoning codes makes no distinctions regarding land values and access to these amenities. Lots near amenities will have higher land values, reflecting the benefit to residents. And higher land values suggest a higher demand for that location. Being close to a rail line, for example, is valuable, which means that densifying is the rational thing to do.

However, in Rosedale, it’s illegal for land values to dictate density because the entire neighborhood has the same set of FAR regulations—all of which “force” one- or two-family homes on residents, regardless of whether this is economically rational or not.

What’s To be Done?

Upzone Rosedale

As I have discussed elsewhere, the first thing to do is to permit the allowable FAR to tick upwards based on the demand and land values. The minimum rezoning throughout the neighborhood should be increased from 0.5 to 1.0, with a corresponding loosening of height limits, plot coverages, and off-street parking requirements.

The zoning regulations should also consider the location of amenities and provide higher FARs on these blocks. Upzoning the corridor along the LIRR and Sunrise Highway seems a no-brainer. If city regulations truly had transit-oriented design (TOD) in mind, this area could be rebuilt as a mixed-use walking neighborhood centered around the train stop.

Likely, the MTA/LIRR owns a significant amount of land along the train lines. A master plan should allow the MTA to lease lots to developers now used only for parking ; this way, the MTR can profit from the density and plow the money into improving service. For that matter, the greater the density along the corridor, the more riders and the greater the revenue.

A Streetcar Named Sunrise Highway

More ambitiously, how about a streetcar line that runs along Sunrise Highway from the city to deep into Long Island, and parallel to the LIRR? Again, the blocks along the highway could be converted into apartments for thousands of people in what could be one of the world’s longest TOD corridors (to build along Sunrise Highway would hardly impact Nassau County’s homeowners, though the Nimbyists would immediately cry foul.)

Legalize ADUs

Another no-brainer is to allow homeowners to create Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs). An ADU is a small additional unit, say a converted garage, basement, or porch, that has separate living space and entrances and is suitable for one- or two-person households. ADUs provide additional income to the property owner and housing options for the very old, young adults, or the single. There are nearly 2,000 single-family homes in Rosedale—imagine each one had an ADU!

Land Value Insurance

One of the biggest obstacles to change is the fear of change—the fear that homeowners will find their house values plummeting as the neighborhood redevelops. Ironically, a densifying community will see increased land values which would help existing property owners. For example, residential land values in Norwood are around $430 per square foot as opposed to $150 for Rosedale, even though Norwood’s median income is less than half of Rosedale’s.

One possible policy is to offer land value insurance to residents. As I have discussed elsewhere, homeowners could take out an insurance policy that would pay out at the time of selling if their land values declined because of rezoning.[3]

The point is that some form of insurance can mitigate fears that partly drive Nimbyism and opposition to rezonings.

Can We Get to Affordable Housing? Think VEAM

The road to affordability, however, begins with systematic thinking. Right now, Nimbyists dictate what happens because they are trying to protect what they have. Parochialism is the order of the day. Residents see changes as a zero-sum game–one neighborhood benefits at the expense of another.

Incentivizing massive redevelopment begins with the idea that all neighborhoods must be ready to chip in their fair share of housing. It also means that people who fear change must see some compensation if they are harmed–to reduce their reluctance of change.

But a big problem is that different government agencies frequently act independently, without any sense that a city is system of inter-connected parts. For example, the Department of City Planning oversees zoning, while the MTA, Department of Transportation, and the Port Authority oversee transportation (each separately from each other). Planning, zoning, and transportation are barely connected, despite the fact that housing and mobility are two sides of the same coin.

While I will have more to say about this in future posts, the road to a better, more affordable city begins with recognizing what I call the VEAM Principle. First is the Value of Land–higher land value places should have more allowable density since land values represent the value of geography. Second is Externalities. Planning polices should reduce shadows and congestion, for example, without imposing undue burdens on what can be built. Third is Affordability. If a neighborhood has low vacancy, it must be upzoned and encouraged to build more units (even above its “fair” share). Affordability cannot come from ad hoc policies and expanding the rent stabilization program. Lastly is Mobility. More housing requires more mobility, which means investments in rail, pedestrian and bike lanes, and driving congestion fees.

If the city truly considers these four elements at the same time, Gotham will get that much closer to solving its affordability crisis.

Continue reading Skynomics Blog posts on New York City real estate here.

—

[1] Rosedale, however, is on the landing path of airplanes. Giant steel birds descend over the houses. It’s a bit unnerving to see it for the first time.

[2] Why the government dictates architectural practice is beyond me. Sure, things like building scale matter, but if a city is going to add a restriction, it should allow a dispensation somewhere else (such as higher lot coverage). Dictating style alone only serves to make housing markets more expensive. IMHO, when the government forces architects to recreate older styles, it makes the neighborhood look more inauthentic.

[3] The program could not insure against the value of both house and land, since house value insurance would incentivize owners to under-maintain their homes.