Jason M. Barr December 23, 2020

The Space Race

At the end of the Roaring Twenties, New York City witnessed a three-way race for the world’s tallest building. First was the Bank of Manhattan Building, at 40 Wall Street, which topped out at 927 feet (283 meters, 70 stories) in November 1929 and officially opened in May 1930. Next came the Chrysler Building (1,046 feet 319 meters, 77 stories), whose final height was riveted into place concurrently with the Bank of Manhattan but was not formally revealed until its rival was finished.

Finally was the granddaddy of them all, the Empire State Building. When its construction was announced in August 1929, it was planned to be 1,000 feet (305 meters, 80 stories) tall. However, after the Chrysler Building was completed in December of that year, five more floors and a 185-foot (56-meter) mooring mast were added. The building topped out in March 1931 at 1,250 feet (381 meters, 102 stories) and officially opened on May 1, 1931, with President Hoover ceremonially illuminating the lobby from Washington D.C.

Out of Gotham

Four decades later, in December 1970, when the north tower of the Twin Towers topped out at 1,368 feet (417 meters, 94 stories), the record was broken once again (both towers officially opened on April 4, 1973). The world’s tallest building then moved to Chicago when the Sears (Willis) Tower topped out at 1,450 feet (442 meters, 110 floors) in May 1973. After that to Kuala Lumpur with the Petronas Towers (1,230 feet, 452 meters, 88 stories) in 1998. Then the Taipei 101 in 2004 (1671 feet, 509 meters, 101 stories). And most recently, in Dubai in 2010, with the Burj Khalifa (2,217 feet, 828 meters, 163 floors).

It is clear that New York has bowed out of the record-breaking game—the very game that it initiated in the 19th century. Between 1875 and 1931, New York City developers beat each other for the world’s tallest skyscraper ten times. What drove the city to build so many record-breakers in the first place, and why did it stop competing?

The Bricks of Ego?

If you ask a random person on the street why New York built so many record-breakers, the typical answer is bound to be “ego.” Ever since societies settled down, titans have built monumental structures. The pharaohs showed off with pyramids, kings with grand palaces, and religions with houses of worship. It thus follows that mega-wealthy business tycoons would show off their wealth by building monuments to themselves or their companies. But in truth, this is a gross oversimplification. Certainly, today’s New York builders have just as large egos as the old days, and if ego were the main driver, they would still be competitive in the height race.

But the fundamental reason that New York kept outdoing itself was that the underlying economics of going tall was so favorable. The tallest of the tall represented the “peak” of the height distribution. Skyscrapers were built to accommodate the city’s rapid growth. Land values were rising while engineering and construction technology were improving—these two factors, more than anything, explain the height races.

The Bricks of Business

If the developer was a national corporation, it would build tall to house its employees and to have an icon of its success. However, most of these companies did not use all the floors; many were rented out to smaller firms. In this way, the corporation received a return on its investment in addition to headquarters.

For the speculative developer, the goal was to fill the building with as many companies as possible; that was relatively easy in the central business districts, which were bubbling with firms eager to rent in the newest, most convenient accommodations. Without the nickels of the thousands of small white-collar businesses, there would have been no space race.

For some builders, however, merely being tall was not enough. Having the tallest was important—either for ego, advertisement, or some combination of both. This was accomplished usually in one of two ways (or both). The first was to increase the profit-maximizing height by erecting a narrow tower on top. While adding the tower was not cheap, it tended to rent for higher rates given the small, sun-filled spaces with amazing views.

Vanity Height

The other strategy was to add a decorative element that had an architectural appeal but was not otherwise occupiable (the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat calls this Vanity Height). The most common was a spire, which could also be used to house machinery and equipment, thus rendering it useful, if not income producing.

The critical point here is that the favorable economics would get a building to a certain profit-maximizing height; with some extra cash, the developer could extend it into the record-breaking zone and still generate a profit. And profitable they were—that is why there were so many of them.

A Brief History of the Record-breakers

Before the Great Depression, there were three generations of record-breakers. Generation I encompassed the last quarter of the 19th century, with a series of buildings that were incrementally taller than what was being built at the time. To break the height barrier, they each added domes or small towers. All of them were built in Lower Manhattan along Broadway or Newspaper Row, by City Hall.

This generation includes the Tribune Building (1875, 260 feet, 79 meters, 9 or 10 stories), the World (Pulitzer) Building (1890, 308 feet, 94 meters, 18 stories), the Manhattan Life Insurance Building (1892, 348 feet, 106 meters, 18 stories), and the Park Row Building (1899, 391 feet, 119 meters, 30 stories)

The Tribune and World Buildings were constructed by newspaper publishers to house their operations and to project the power of their newspapers and American journalism in general. The Manhattan Life Building was constructed as a headquarters. The company was also participating in an insurance company height race, started by the Equitable Life Assurance Society and the New York Life Insurance Company, whose buildings were both completed in 1870. The Park Row Building was a speculative venture. It was initiated by prominent New York lawyer and politician, William Mills Ivins, but subsequently led by financier August Belmont. The building housed the offices of his Interborough Rapid Transit company, which built the city’s first subway line.

The Next Generation

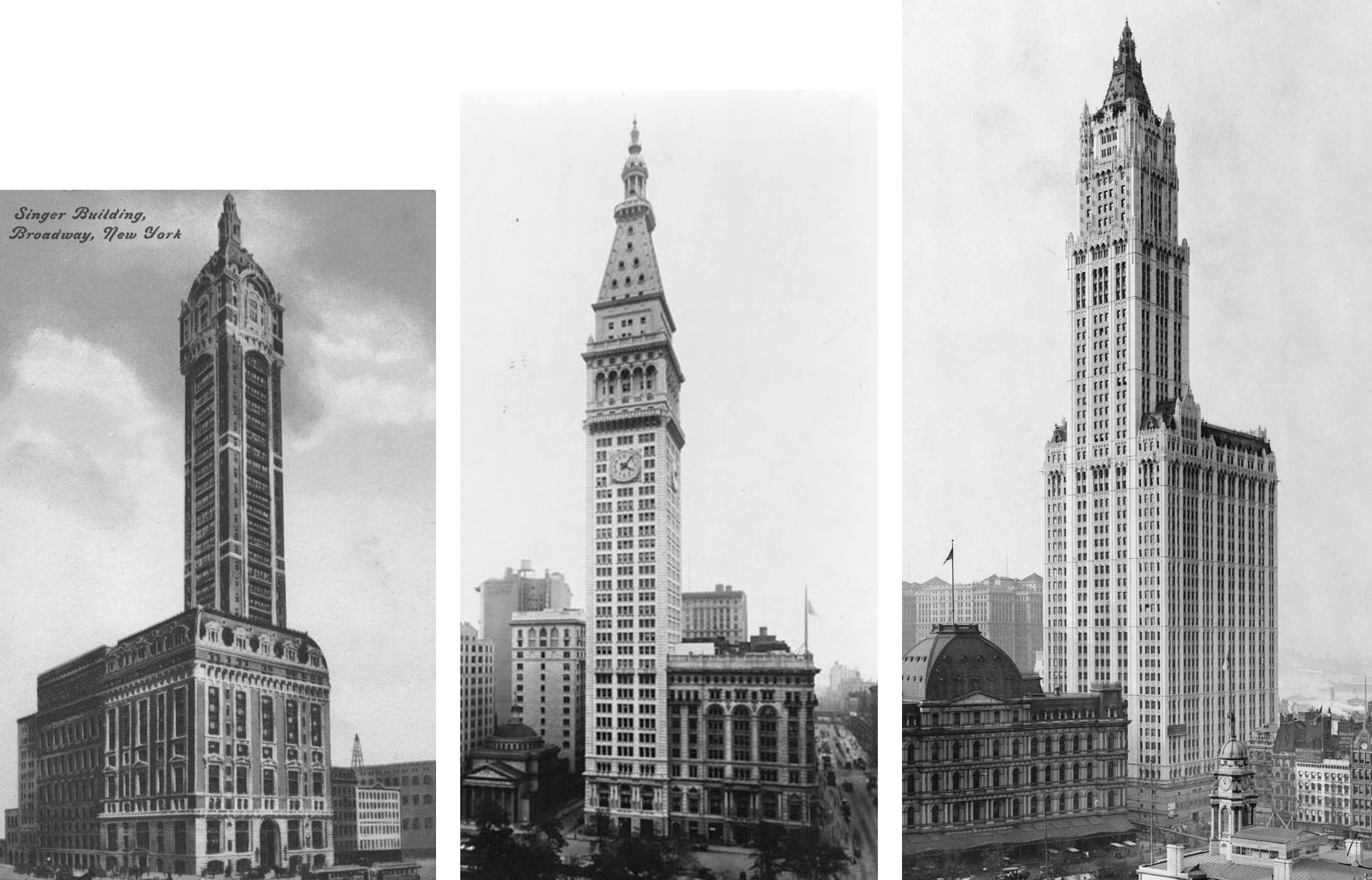

Generation II was the twentieth century before World War I. This crop included the Singer Building (1908, 674 feet, 205 meters, 41 stories), the Metropolitan Life Tower (1909, 700 feet, 210 meters, 50 stories), and the Woolworth Building (1913, 792 feet, 241 meters, 55 stories). These represented the flowering of all-steel skeletal frames. They were each built by large corporations seeking to house their businesses and produce an icon for their companies.

The Singer Building was built for the Singer Sewing Machine Company and was essentially a 14-story office building with a super-thin, goosenecked 27-story tower plunked down on its mansard roof. The MetLife Building was a pure tower modeled after the St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice. The Woolworth Building, built by retail store magnate, F. W. Woolworth, was a 30-story office building with a 25-story tower.

Generation III

Generation III was the three Deco Giants: The Bank of Manhattan, the Chrysler, and the Empire State Buildings. They were each built after the implementation of the city’s 1916 zoning codes, which mandated that buildings be set back from the street as they rose higher, thus promoting the wedding cake architectural style. A builder could erect a tower as high as he wanted if the footprint were less than 25% of the lot. Given the large lots of these three projects, the tower portions were economically viable.

The Bank of Manhattan building, at 40 Wall Street, was conceived as a speculative project by financier George Ohrstrom. He convinced the Bank of Manhattan to rent 100,000 square feet (9,290 m2) for its headquarters. In contrast, Walter Chrysler built the Chrysler Building on his own account. However, in 1928, when he initiated the project, the Chrysler Motor Corp. was only three years old; in this sense, the line between Chrysler, the man, and Chrysler, the company, was very thin. Finally, the Empire State Building was erected as a speculative venture by former New York State Governor Al Smith and financier and former General Motors executive John J. Raskob. They initiated the project in the late summer of 1929 as Manhattan rents continued to skyrocket.

The Twin Towers

After the completion of these “three amigos,” 15 years of depression and war followed. When New York returned to the business of business, the economics of recording-breaking buildings had changed. Industrial cities like Gotham saw their employment bases shrink due to the rise of sunbelt cities and a drop in the quality of life. New York was still skyscraper central. However, construction cost inflation and flat office rents, combined with a more restrictive zoning regime (initiated in 1961), meant that the economics of private-sector record-breakers no longer worked.

The World Trade Center was a government project, built by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) with the aid of New York State and New York City. It was conceived during the 1960s when governments around the U.S. were promoting slum clearance and urban renewal projects. The World Trade Center, with 10 million square feet of office space over 16 acres, was viewed as a means to improve the fortunes of lower Manhattan, which had fallen on hard times. The Twin Towers would never have been built by private developers; however, they proved profitable over time.

An Economic Analysis of the Record-breakers

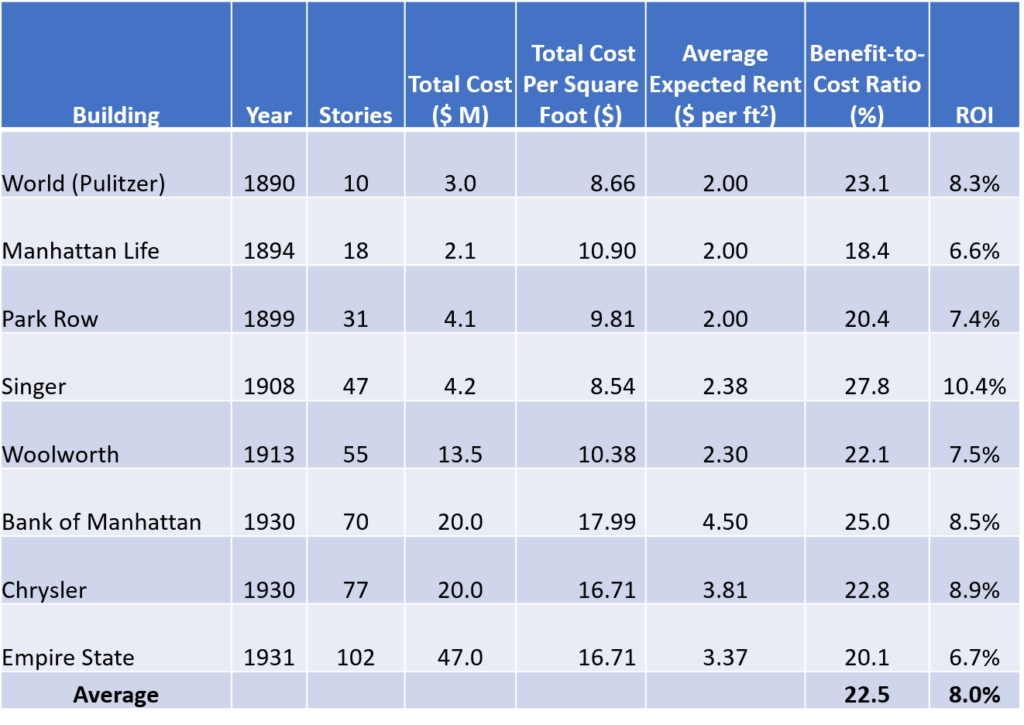

A rational developer goes tall when the expectation is that the high cost will be rewarded with a large income. Developers typically take the current rents as the starting point. As the potential income relative to costs rises, it motivates developers to add extra height. To investigate the degree to which the record-breakers in New York were tied to the economic fundamentals and not loosely moored to them because of raging egos, I turned to the historical data.

To compare apples to apples and keep the analysis relatively simple, we can look at the average expected annual rent per square foot for the building at the time of opening relative to the per-square-foot costs to erect each building (including land costs). We can call this the Benefit-to-Cost Ratio. (Details on data, sources, and analysis are here.) If the Benefit-to-Cost Ratio for these buildings are high, it suggests a strong economic basis for these buildings; if not, it suggests emotions dominate the decision-making process.

Based on a review of this data, the conclusion is that before World War II, the record-breaking buildings were economically justified. In fact, the average ratio of rents to construction costs was nearly 23% (with none lower than 18%). This translated into an average estimated return on investment (ROI) of 8.0%, which is quite respectable. This is not to say that every building went on to earn very high profits or that the developers’ expectations were fully realized; but rather, it is to say that these projects all had a strong economic logic and that ego was second to economics.

This finding also includes the Empire State Building, which was green-lighted in the summer of 1929 and whose construction ran through 1930, when the New York real estate market was still chugging along. At the end of 1930, when the market took a deep dive, the structure was almost finished and had rental contracts on its books. Nearly every building in New York suffered tremendously in 1931. The only reason the Empire State Building was ridiculed so resoundingly was because of its visibility.

Office Towers Today

How do the economics of office towers for Manhattan compare today? To answer this, I collected information on New York’s newest office skyscraper—One Vanderbilt (1,401 feet, 427 meters, 65 stories)—completed this year. While it is the city’s fourth-tallest building (and second-tallest office building), it is quite stubby when compared to the 828-meter Burj Khalifa. Around the globe, it is the 26th tallest skyscraper.

The total project cost for land and building (and upgrades to local infrastructure) came in around $3.3 billion. Using the expected figure of average office rents of $178 per square foot (ignoring the COVID-19 pandemic) gives a Benefit-to-Cost Ratio of 9.4% (and an estimated ROI of 4%), half of the average from the pre-World War II period. In other words, going super-supertall today in the office sector does not appear all that profitable.

What Will it Take for New York to Build the World’s Tallest Building?

What kind of economics would incentivize the private sector to build the next world’s tallest tower in New York City? For the sake of comparison, let’s say that the building will be a centrally located office tower constructed within current zoning allowances. Using One Vanderbilt’s construction costs as a benchmark, let’s assume that the project can be built for $2,000 per square foot, including both land and construction costs.

Further, let’s assume that the Benefit-to-Cost Ratio has to be at least 20% to make a record-breaking building work, just like in the old days. Thist would mean that office rents would have to be more than double what was estimated for One Vanderbilt, given the costs. Rents would have to average around $400 per square for a 21st-century version of the Empire State or Woolworth Building to pay. Something unlikely to happen any time soon, if ever.

The Bricks of Ambition

Merely talking about New York constructing the next world’s tallest building, is of course, controversial. Tall buildings had their detractors a century ago, and NIMBYists do what they can to stop them today. But it’s important to understand that in the long sweep of New York’s history, economic forces have driven the rise and growth of its skyline. This is not to say that every single project had a rock-solid economic foundation or that its impacts were purely benign, but it is to say that New York became the world’s greatest metropolis because it was able to build up to accommodate the growth of its commerce and population.

Someday, if the economics should favor a motivated developer to push her building one kilometer or higher into the sky, I say we should celebrate it. New York was, is, and will always be, a city of strivers. The skyline was built from the bricks of ambition, and without it, New York would not be New York.

Thanks to Maria Thompson for editorial assistance.