Jason M. Barr October 19, 2018

A Brief History of Homo Sapiens

If we look back over the long sweep of Earth history, Homo sapiens has succeeded not only because it can adapt to nearly any environment on the planet, but also because it can change the environment to suit its needs and wants at any given time. One can say that technological innovation is the defining characteristic of Homo sapiens’ success—the ability to consciously manipulate and alter the Earth’s materials to increase productivity and product variety. Arguably this started with the creation of stone tools and animal-skin clothing. Next came genetic experiments with grains and goats, so that calories came to it, rather than the other way around. After that, the processing of metals allowed for large scale warfare and more food.

But the original evolutionary path of Homo sapiens was within small hunter-gatherer bands of only a few dozen people. This produced within them a deep sense of group loyalty, and an immediate impulse to define who was a member of the tribe and who was not.[1] The success of any one individual depended on collective action and support, and thus individuals needed to know who they could count on to help secure calories, raise their young, and ward off predators.

Trade, Warfare, and Civilization

Yet despite the instinct to readily designate social boundaries and block “outsiders,” the greatest plot twist of human history is that technological innovation—designed to give a competitive advantage over other humans and nonhumans alike—had the unintended consequence of drawing the diverse and scattered tribes of Homo sapiens into one common global community, by producing the three great pillars of the modern world: trade, warfare, and civilization.

The domestication of plants and animals, combined with metal tools, produced a surplus of calories. From this, humans were able to specialize in other pursuits, while living off the bounty. Kings emerged to both centralize economic and political life and to, literally and figuratively, enjoy the fruits of power. Collectively, rulers, priests, bureaucrats, craftsman, and traders invented the city to reduce their transportation costs, and better coordinate their actions. They surrounded themselves with large defensive walls, since rival tribes were eager to plunder the surplus. The ruling class wanted to keep track of their possessions, and so they developed writing as a form of record keeping, which eventually flowered into much more than that. Accounting gave rise to Plato, Shakespeare, Marx, and Einstein.

The Romans, in their quest for tribute and trade, used their superior martial skills and weapons to unite the lands around the Mediterranean. The Pax Romana allowed for a flowering of trade. Yet despite the perks of Empire, the subjugated were never content with subjugation. The tribal instincts were too great. The arms race continued apace. Stone Age spears were replaced with Bronze Age weapons and armor, which were replaced with iron swords and chariots.

Life in the 21st Century

When Western Europe awoke from its thousand-year slumber after the fall of the Roman Empire, it spread markets, finance, and Adam Smith throughout the rest of the world. Now Empire was merged with Economics. When foreigners were reluctant to welcome new traders, markets were opened by force.

The British, in their quest for trade and tribute, used their superior martial skills and weapons to unite the lands around the globe. The Pax Britannica allowed for a flowering of trade. Yet despite the perks of Empire, the subjugated were never content with subjugation. The tribal instincts were too great. The arms race continued apace. Iron swords and chariots were replaced with guns, germs, and steel, which were eventually replaced with F-15s and nuclear weapons.

By the middle of the 20th century, with the end of World War II, Empire was laid to rest.[2] Technological innovations made war too costly and too destructive, and the seductive web of the marketplace was now too strong. And so Homo sapiens set itself on the path of globalization, not through conquest, but through comparative advantage, branding, and planned obsolescence. To be “Westernized” was to adopt the lifestyle of consumerism over aggression, and to accept the global flows of capital, labor, and finance in the name of growth and efficiency.

The Promises of Globalization

The embrace of global capitalism has been premised on a few fundamental assumptions. First is that it can tightly link effort with reward. People who invest in improving their skills and work hard will enjoy a higher income and greater standard of living. This will, in turn, generate economic growth, further cementing the bond between effort and reward.

A second, but perhaps less discussed assumption, is that if humans are to suppress their instincts for tribalism, then the rewards of economic growth must be shared in a manner that seems fair to all involved. “Fairness” is defined as “impartial and just treatment or behavior without favoritism or discrimination.” But what this really means is that humans automatically feel victimized when one “tribe” is seemingly privileged over another; or that effort is not rewarded because of “tribal” reasons. We turn to the law and the marketplace for blind fairness to all, which further links effort and reward.

For several decades after World War II these assumptions seemed to largely bear themselves out: nations that embraced capitalism saw their fortunes improve. Joining the global order generated peace and contentment. But these assumptions are starting to peel away, as we move inexorably towards a light-speed economy.

A Hyper-Mobile Planet

One of the hallmarks of globalization is a reduction in trade barriers, and transportation and communication costs. This allows resources to flow to their most productive uses, generating economic efficiency and lower prices for consumers. The iPhone is a perfect example of this. Product and software development occurs in Cupertino, California. Yet the actual phone is constructed in China, and the parts are delivered from factories throughout the world. Only a fraction of the total value of the phone itself is allocated to the home county. The iPhone is arguably the world’s most popular product. For a relatively affordable price, Homo sapiens can get access to a tiny flat box that provides nearly an unlimited number of applications in the palm of their opposable-thumbed hands, and which simultaneously connects each human to the Great Global Social Network.

Frozen Wages and Rising Income Inequality

The attempt to build better and cheaper products has generated a loss of well-paid manufacturing jobs in the United States, and rising income inequality. This has contributed to the “donutization” of the American workforce, where high-tech high skilled jobs are richly compensated in the big cities, and the rest are lower paid service workers, who have seen their wages decline. Furthermore, even though businesses are increasing their productivity, they are no longer passing this extra revenue onto labor. Rather corporate owners and their hired managers are retaining more of the value of employees’ efforts. The global consolidation of high-tech manufacturing also means that there are fewer firms, each of whom now have greater power over workers to set lower wages. The future of work is also uncertain due to the automation of jobs by computers and robots.

The De-Coupling Effect

A large segment of the U. S. population is experiencing the American Dream in reverse, with declining social and economic mobility. This is also contributing to the dramatic drop in labor force participation, especially among men, who are increasingly unable to find meaningful work. One of the great ironies of the American economy is that, even as capital and labor are much more mobile world over, the geographic mobility of workers in parts of the United States is falling. Today and historically, moving to growing regions has been an important component of achieving higher wages. Yet an increasing segment of the population is stuck in place, unable to drink from the fountain of the global economy. Those with skills move to the big cities; those without them fall further behind.

Thus, for large segment of the population, technological change has promoted a more tenuous link between effort and reward. Yet part and parcel of the material benefits and fairness of capitalism is that effort and productivity are rewarded accordingly. The obvious fall back to this de-coupling is to seek comfort in tribe, the ultimate security blanket against the failures of globalization.

Technology and the Big Sort

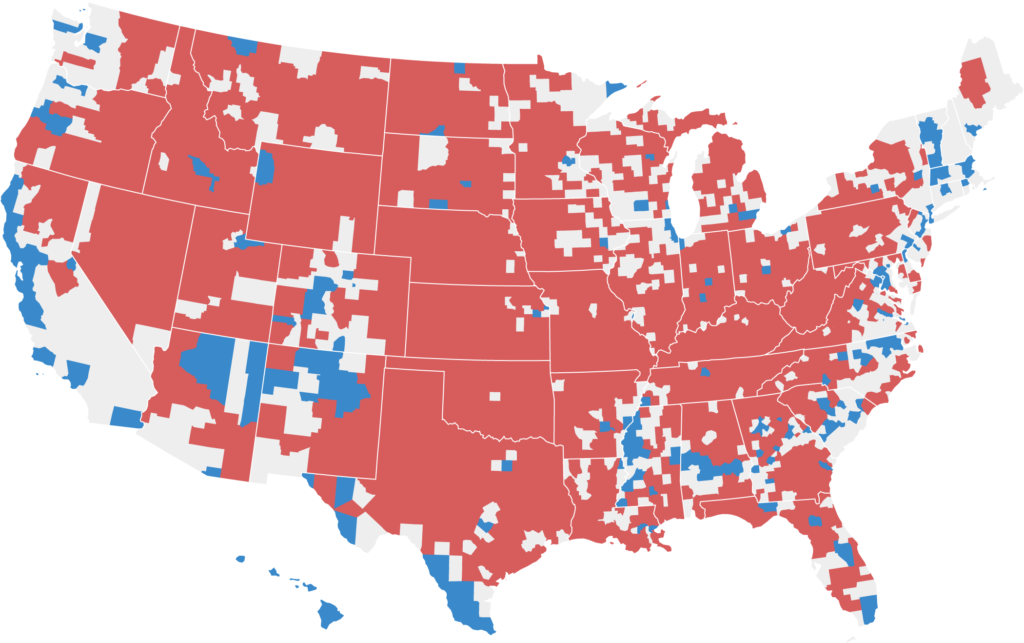

Parallel to the economic divergence is the changing geography of politics. In the United States, more and more people live in neighborhoods that are politically homogeneous, sorting themselves into their own political tribes. Long term increases in wealth since World War II have allowed Homo sapiens the luxury of seeking out neighborhoods that provide the tribe-oriented social interactions they require.

As Bill Bishop documents in The Big Sort:

Freed from want and worry, people were reording their lives around their values, their tastes and their beliefs. They were clustering in communities of like-mindedness, and not just geographically. Churches grow more politically homogenous during this time, and so did civic clubs, volunteer organizations, and dramatically, political parties. …Prosperity had altered what people wanted out of life and what they expect from government, their churches, and their neighborhoods.

The Cost of Information

For people to sort themselves, they need to easily identify each other. Today, the cost of generating and acquiring information is as cheap as its ever been. A quick Google or Facebook search can identify immediately where the tribes live and how they live their lives. Thus, technological change intended to make the world flatter is making the world “hillier” by allowing for greater social and economic separation.

Innovations in the internet, social media, cable television, and smart phones were all designed to bring consumers better products that more directly targeted their interests. But it has also allowed for the rise of tribalist media and “political entrepreneurs” who stoke the passions of tribalism for economic and political gain. While academic research is mixed on the effect of new media being strictly an “echo chamber,” it is clear that many outlets are exploiting the demand for tribalism by propagating feelings victimhood of the target audience while promoting “otherism” among those who don’t consume the tribalist hype. Geographic segregation reinforces and further entrenches the divide.

Tribalism versus Terranism in the 21st Century: Lessons for the Future?

The changing nature of production and work, and the fall of global economic barriers, has exacerbated the tensions between globalism and tribalism. As much as people desire the perks of globalization—such as cheaper and more varied goods and services—many cannot shake the evolutionary instincts toward tribalism, especially when they feel that fairness from the global order has eluded them.

This battle between globalization and tribalism has been ongoing for at least six millennia, ever since Homo sapiens settled down into cities. But the long sweep of history shows that the trajectory towards a global future is nearly inevitable.[3] Tribalism—by its very nature—contains the forces that create terranism. War in the name of tribalism creates globalization. Trade for self-betterment creates globalization. Innovations, such as airplane and the internet, erodes barriers and increases connectivity. Once ignited, globalization generates greater income, health, and life-satisfaction that humans have come to depend on.

Our Common Future?

The question then is how to do we learn the right lessons from history? As much as tribalists want to satisfy that burning itch buried deep within them—an itch now being fueled by vanishing barriers—they cannot stop the forces toward a common global humanity, though they can slow it down and make the trajectory costlier and more perilous. There are just two ways our global future can emerge—from the ashes of war or from the promise of shared prosperity.

So how can we use the technological innovations at our disposal to make sure the price of tribalism is too high? For this we need to better learn from our collective history, and to be ready to employ those lessons before it’s too late.[4]

[Thanks to Troy Tassier for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this post. The opinions contained herein are only those of the author.]

—

[1] Why is it that when we meet someone for the first time, our instinct is to ask them where they are from? If they should mention they are from the same hometown, for example, we immediately feel a sense of kinship—that they are member of some hypothetical tribe to which we both belong.

[2] Or at least, WWII ended the last of the martial empires. That the Cold War was cold was due to the fact the technological innovation in war-making all but assured the self-destruction of Homo sapiens itself if war should turn hot. Fortunately, the cost of the Cold War eventually caused it to collapse under its own weight.

[3] Unless we destroy ourselves first through climate change or World War III.

[4] In a future blog post, I will discuss how we can better learn from our future. Or rather, what lessons the futurism of Star Trek has for us today.