Jason M. Barr January 17, 2023

Gotham has a housing affordability problem. Gotham has a transit problem. There’s a simple solution to help both. Given New York’s decentralized governance structure, however, the right hand—transit—doesn’t speak to the left hand—city planning. The result: vast resources are needlessly wasted. It’s high time Transit and Planning became friends (or more!).

The Housing Problem

Simply put, housing supply has been unable to keep up with the demand to live, work, and play in the Big Apple. The result: many New Yorkers can’t make ends meet. In 2021, more than half of the city’s renters—nearly one million households—were rent burdened, in that they paid more than 30% of their incomes toward rent; one-third were severely rent burdened, paying more than half of their income for rent. Only 30% of New Yorkers earn enough to have a “living wage”—the minimum amount to pay for food, clothing, housing, health care, child care, transportation, and taxes.

The vacancy rate for apartments that rent for less than $1,500 per month is below 1%. In essence, it is virtually impossible for low-income New Yorkers to find affordable housing. Governor Hochul is pushing for 800,000 new units statewide in the next decade. If the City wants to hit its target, it had better rethink its housing strategy.

The Subway Problem

When the Covid Pandemic hit in the spring of 2020, the platforms became ghost towns. Ridership was a mere 7% of what it had been just a couple of months earlier, and today it’s up to about 70% of pre-Pandemic levels. But even before Covid, the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) struggled to balance its books.

The number of straphangers in the 21st century is far from the peak in the late 1940s. Fewer riders and expensive maintenance and operating costs spell financial trouble. Even though the MTA’s recent budget includes a 5.5% fare hike, the subway would cease to function without government subsidies and dedicated tax revenues.

And yet, transit riders and city advocates are scratching their heads. What’s to be done to get ridership back up? There remains too much competition from automobiles, but politicians are not interested in reducing car dependence. Drivers vote, and they don’t like their tolls going up.

But the answer is in plain sight: The MTA and the City Planning Commission should be united in a mission to create a large-scale transit-oriented-development (TOD) program.

Housing Gotham

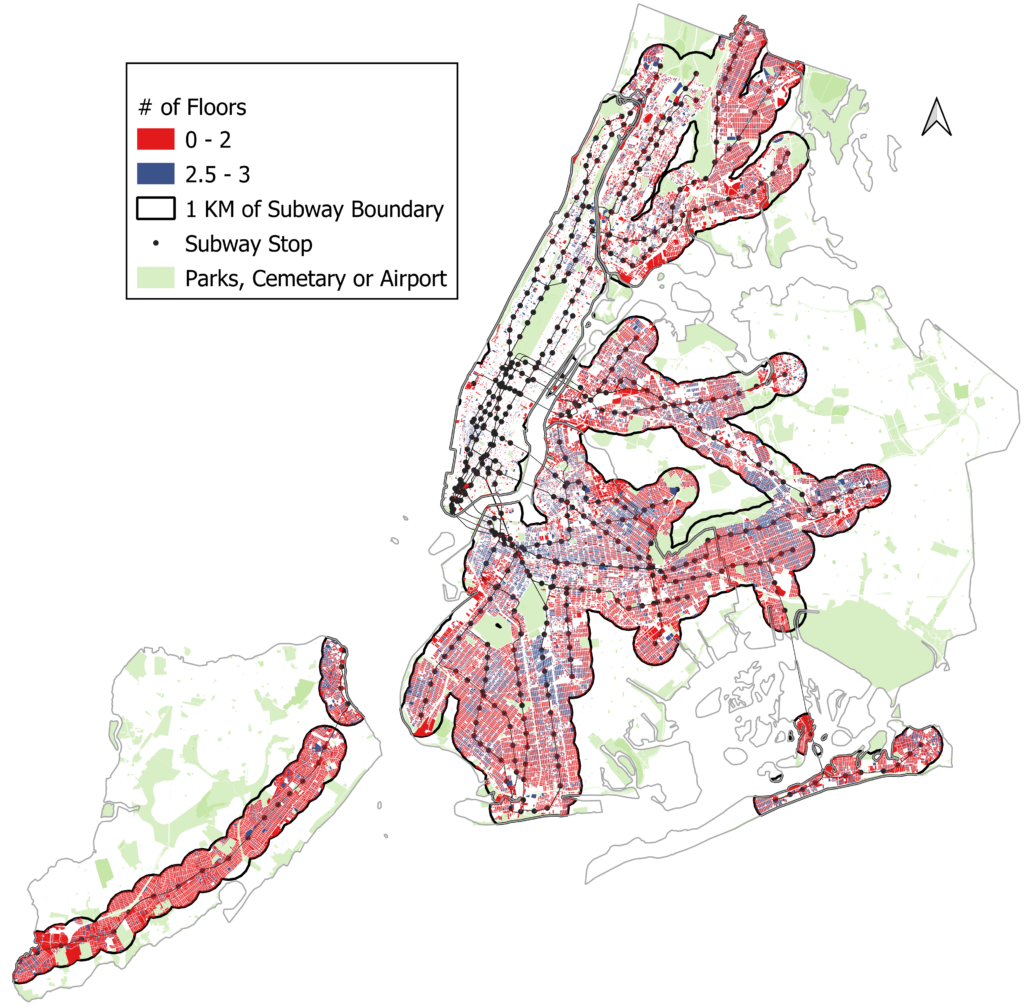

When you put building height and zoning maps together with the subway map, you can see how much land is “wasted.” To keep things simple, let’s zoom in on that part of New York within one kilometer (0.62 miles) of a subway station (see the figure above). The typical person would need to walk about 10-15 minutes to catch a train, a reasonable distance to focus on transit-oriented zoning.

Low-rise Gotham

A look at the buildings reveals a shocking fact: Outside of Manhattan, 63% of all properties within one kilometer (1KM) of a subway have two stories or less, while 92% are three stories or less. (Data sources and calculations are here.)

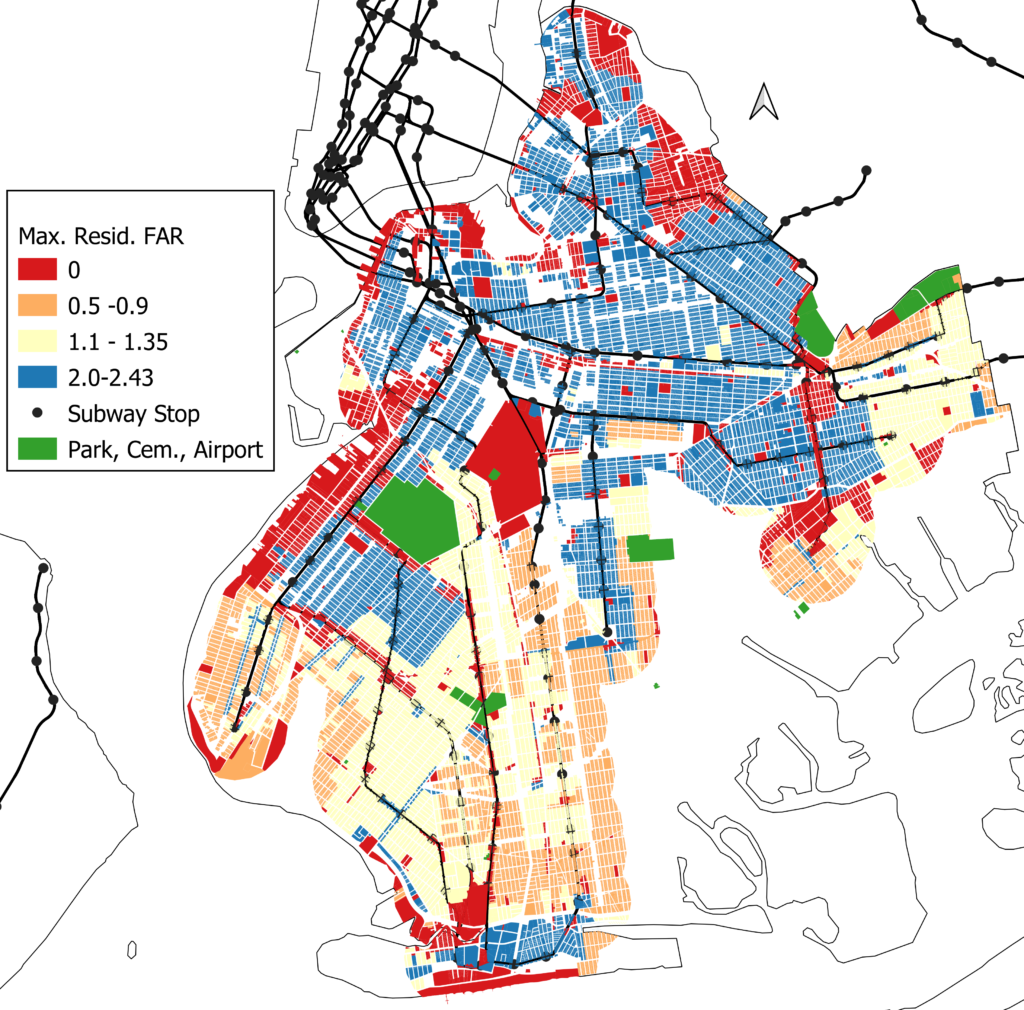

Turning to zoning, the City regulates building density by placing caps on the so-called Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which limits the total floor area relative to the lot size. A maximum allowable FAR of one, for example, means that a property owner can build a one-story building on the whole lot or a two-story structure on half the lot. A FAR of one limits the property to either a one-story office or retail or a one- or two-family home.

Outside of Manhattan, there are two million housing units within one kilometer of a subway stop. 63% have a maximum allowable FAR of 1.35 or less. In other words, nearly two-thirds of properties are required—by law—to be one or two-family homes. To build a typical apartment building with ten stories requires a FAR of at least 6.

Zoned Out

Also, within the 1KM zone, many structures were built before the FAR caps were imposed in 1961 and are currently above the maximum allowable FAR (since they were grandfathered). Tearing down a building, in this case, to build a new one, is uneconomic because the developer would need to produce less floor space than what’s there now. 56% of residential structures are either overbuilt or within 25% of the allowable maximum, a de facto limit, given all the hurdles to redevelopment.

In short, the vast majority of residential structures within walking distance are three stories or less and are legally required to stay that way. What’s a good phrase for this? How about anti-useful-transit-oriented (AUTO) zoning (AUTOZone)?

What Would Real TOD Look Like?

How many more units and subway riders could Gotham have if it adopted a relatively modest version of transit-oriented zoning? Here are a few examples.

Case I

Let’s exclude Manhattan and say the City upzones all residential properties to a maximum FAR of 4 if within one kilometer of a subway stop. If an existing building has a residential FAR above 4, it keeps that value.[1]

Under this scenario, if fully built out New York city could build about 4 million net new units, and with few buildings taller than ten stories (calculations and assumptions here). As a side note, Mayor Adam’s best projection for office-to-residential conversions is 20,000 new units.

The average building would have 14 units versus 4.7 now—hardly mammoth skyscrapers. With a relatively modest increase in zoning caps, Gotham could get an enormous number of units and new straphangers. Based on my estimates, a 10% increase in the population within a one-kilometer (0.62 miles) radius of a subway stop increases ridership at that stop by 7%. Given those four million new units, that’s a new population of about 10 million people!

Case II

Well, maybe you say that a maximum FAR of 4 is too high. Let’s repeat the exercise with a cap of 3 (excluding Manhattan) or the current FAR on the property, whichever is higher. This scenario gets us a net increase in units of 2.8 million units, with a corresponding population increase of seven million residents.

Case III

Perhaps you say it’s better to have a sliding scale, with higher FAR caps closer to the stops and diminishing further away. Let’s say we go with a maximum FAR of 6 for, say, 0 to 200 meters (0.12 miles), 4 for 200 to 500 meters (0.31 miles), and 3 for 500 to 1000 meters (0.62 miles). The results get us back to something similar to Case I, with a net increase of some 4 million units and a net increase in the population of 10 million.

The Bigger Picture

Under these scenarios, based on relatively modest changes in the FAR restrictions, we can potentially get tremendous increases in housing units and transit riders. Ironically, we are not talking about Manhattan-like densities. Instead, these exercises show the need to replace the many one- and two- family homes with low- and mid-rise apartment buildings. The scenario numbers are so high because we are talking about vast quantities of urban space throughout the four boroughs—75 square miles of developable land (excluding streets and parks). By forcing most of the city to be three stories or less makes, vast acreage goes wasted; the result is unaffordable housing and an underutilized subway system.

Getting to TOD

I suggest two possible strategies for getting to transit-oriented development. One is relatively “easy” in that it follows the standard approaches used by the City over the last few decades—it’s the “carrot” approach of incentivizing developers but not having any “sticks” to punish inaction. The second would be more controversial but is not without precedent.

The “Carrot” Approach

The first approach is to systematically upzone for more housing in neighborhoods within either 0.5 miles or 1 kilometer of a subway stop. The upzoning can be done strategically to encourage relatively more units at particularly underutilized stops.

The upzonings must be generous enough to incentivize the construction of apartment buildings. FARs of at least four near the subway lines are likely necessary. A more flexible air rights market can help redistribute FAR more efficiently to where it is needed.

The upzonings would also come with generous construction or tax subsidies. This type of program would be similar to New York’s recently-lapsed 421a program, which gave large tax breaks to developers, generally with strings attached to provide a certain amount of affordable units.

The “True Friends” Strategy

Another strategy is arguably more controversial and would run into greater resistance. But it could be more helpful to the MTA’s long run financial position (and reduce its dependence on taxes and subsidies). This approach would be like the Hong Kong model, where the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway (MTR) Corp. owns the land around all its transit stops. Between the sale of development rights, income from rents and ridership, the MTR operates without any state subsidies and runs at a profit!

In the case of New York, the process would need to unfold like the current Penn Station Revitalization plan. The state declares particular lots as “blighted” and takes ownership through the eminent domain process (after compensating the owners). The designated agency sells the development rights.

Regarding the TOD for the subway, officials would create Special TOD Zones. The land in condemned and brought under the ownership of the MTA, which sells the development rights through long-term ground leases. As the property owner, the MTA gets the land lease revenue to help run the subway system.

Creative zoning can also allow the MTA to develop property on the elevated lines themselves, say above or inside the stations to provide more retail and other services. Similarly, in underground stations, where practical, the MTA can expand the subterranean space for mini-malls or other forms of commercial space. Much of this would make sense if it had a “captured audience” from denser neighborhoods.

A TOF (Transit-Oriented Future)?

The good news is that Governor Hochul and Mayor Adams have recently begun discussing the need to address the housing affordability problem and the role that transit-oriented development can play. However, so far, no substantive policy proposals have been put forward, and it’s likely that, without meaningful reform, Nimby Nation will block significant growth in New York’s housing stock.

As I have discussed elsewhere, policies for change require both carrots—incentives and payouts—and sticks—punishments for inaction. However, real progress will only occur when those seeking to prevent change come to see change as being in their economic and political interest.

The way to do this is to create strong inducements for a pro-housing and TOD environment. Examples include:

- Land value insurance that insures homeowners against loss in property values due to neighborhood redevelopments.

- Universal congestion pricing on roads, bridges, buses, and subways.

- Renter savings accounts that allow renters to earn “equity” in their apartments.

- Automatic local public services upgrades that are triggered when population densities hit certain thresholds.

- Land value taxation that taxes land values at a higher rate than building values.

Political leaders must realize that the status quo is no longer sufficient to handle our current problems. They require new leadership, governance, and policies. The success of New York’s vast subway system is being thwarted by its stringent zoning regime. It’s high time that Transit and Planning became friends (or more!) and that Gotham’s leaders kindle the relationship.

—

[1] Note for this and the remaining exercises, I treat Staten Island the same as the other outer boroughs in terms of FAR changes.