Jason M. Barr May 16, 2019

Congestion Pricing for Manhattan

This past April, New York State passed a law allowing congestion pricing in Manhattan. It will take effect sometime by the end of 2020. Drivers will be charged a fee, likely around $14, to enter the island south of 60th Street. The plan, similar to those already in effect in London and Stockholm, aims to reduce the number of cars and generate revenue for mass transit improvements. Implementation in European cities shows that it can work. And while the congestion pricing plan is reasonable and likely to achieve its main goal, it completely ignores the city’s larger transportation problems.[1]

New York: We Have a Problem

Consider this: the New York City metropolitan region has a population of 20 million people, scattered throughout 25 counties in three states. It is, evidently, the largest metropolitan area in the world by land mass, at some 4500 square miles. Assuming that the New York State rate of 0.54 cars per person applies to the region, that means that nearly 11 million passenger cars can possibly be on the roads on any given day, not to mention commercial and freight vehicles.

But a large sprawled out population may or may not be a problem. It all depends on the transportation system’s efficiency. Here is where the real problem lies. Relative to the 125 most populous metro areas in the United States, the New York metro area ranks worst on commuting times. The system is incapable of properly of providing freedom of mobility without undue delay or frustration. Gridlock is a huge waste of resources and diminishes productivity and well-being.

A Brief History of New York City Transportation

Before we move forward to a policy plan, however, it’s important to go back and review the history of transportation investments in New York. Two hundred years ago, the foot was the main mode of travel. Stagecoaches and sailboats could take travelers further afield. But the idea of commuting was non-existent. People lived and worked in the same place or very close by.

Mass Transit is Born

Things started to change with the development of the urban omnibus, in 1829. As a stagecoach outfitted for local travel, it made intra-city mass transit possible. But the real innovation was the horse-drawn streetcar, first introduced in Manhattan in 1832. By embedding rails in the street, fewer horses could pull more people. This was the first time in New York City history that commuting—the separation of work and home—became feasible. It’s also when we see the birth of suburbanization, where middle- and upper-class households moved out to the leafier fringes of the city (in this case around Washington Square park and lower Fifth Avenue). Soon the island was crisscrossed with mass transit.

Els, Trolleys, and Subways

But horses eat and poop a lot. They can only work so many hours a day, and their horsepower is limited. After Thomas Edison demonstrated the success of generating electricity in 1882, trolleys soon replaced streetcars. Travel was now even cheaper and faster, and allowed for a further expansion of the city.

The next innovation was in rapid transit: elevated railroads, sprang up in the 1870s and funneled people up and down Manhattan from the Battery to the Bronx and all places in between. This, again, allowed for a continued expansion of the city’s footprint. But the Els were load and smoky and put streets in shade. Thus came the subway (and the dismantling of the Els). The first line opened in 1904, running from City Hall to the Bronx. Its success prompted a massive building effort, so that by 1940 there was some 700 miles of trackage to all corners of the city. The Golden Age of the New York City subway was during the first half of the 20th century. It allowed people the freedom to quickly and cheaply travel distances far and wide within the city. Once again, the city expanded outward as a result. But by 1950, the subway system was considered complete and hasn’t grown in any material way since then.

The Rise of the Automobile

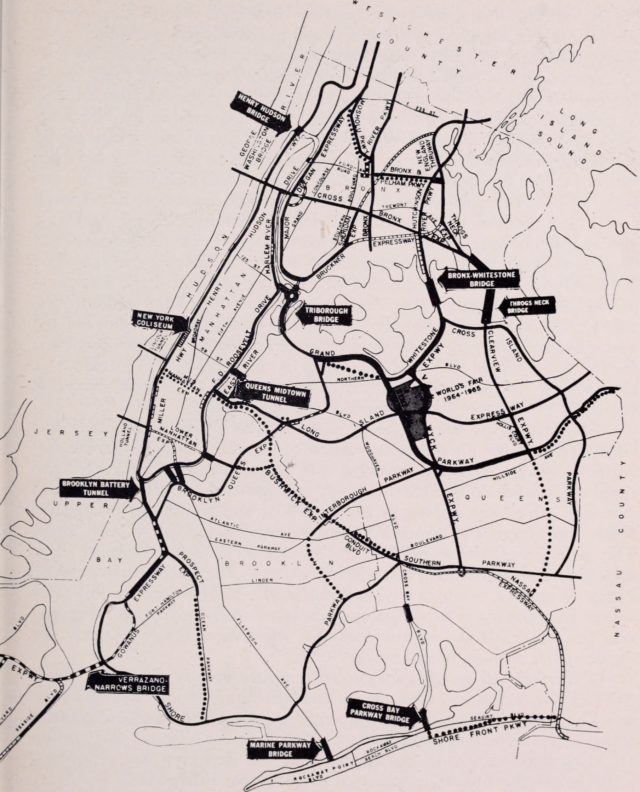

Though significant investments in car-based infrastructure were made in the 1920s, the real action happened after World War II. New York, like other cities, went on a highway building spree, while simultaneously dismantling its trolley network. From the 1930s to the 1960s, New York’s master builder, Robert Moses, skillfully amassed the resources to create a modern road system, including parkways, highways, bridges and tunnels. The automobile and its highways allowed the New York region to grow to 20 million.

In 1968, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller forced Robert Moses out of power. With Moses gone, New York’s road building spree came to a halt. Moses apparently loved to utter the phrase, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs.” By 1968, people were tired of eating omelets. The entire transportation system was considered complete, and no one had the will, the energy, or the money to do much about it.

Transportation and the City

When we step back to consider why cities exist, the answer is to eliminate the barriers of geography. The city is a means by which the spaces between people are reduced as much as possible: a worker is more easily united with employment; the employer is more easily united with the worker, and firms are more easily connected to other firms. People can more easily fulfill their social, economic, psychological, and cultural needs. The city is thus a set of structures—buildings, roads, spaces–that allow people the benefit of living their lives in a more productive way. The city is a mobility machine.

The history of the New York City region demonstrates that as new transportation innovations emerged, the city embraced their construction as a way to increase the efficiency of movement. As the costs of commuting fell, the city expanded to accommodate a larger population. The original New York, founded by the Dutch in 1624, was just a tiny colony on the toe of Manhattan. Today the region is America’s largest and most important metropolis, in no small part because of the transportation investments that were made.

Too Fat for those Old Jeans

And yet, there have been no significant changes to the transportation network in over half a century—no revolutions in modes of transport, no expansion of subways or highways or commuter lines. Despite the fact that the city’s economy and population continue to grow, we are stuck with exactly the same system that residents had when Richard Nixon was president. It was never designed to accommodate 20 million people and the trade and economic activity they generate. The transportation system is like an overweight, middle-aged man trying to cram into the same pair of jeans he wore in college.

A 21st Century Plan for a 20th Century Network

The current transportation network is fixed and too small to operate in its current haphazard fashion. While the Metropolitan Transit Authority runs the subways, buses, and commuter rails, there is little or no coordination among the different modes of travel. Furthermore, there is no coordination of the tolls from the panoply of bridges and tunnels in the region. Hudson River crossings are controlled by the Port Authority who set their own tolls. East River and Harlem River crossing can either be free, or have low or expensive tolls depending on where you cross. The tolls do not float according to the number of users who want to use a particular bridge. If one car or 10,000 cars want to cross, everyone pays the same price (though there is often peak pricing during rush hour).

Because transportation systems are inherently regional, they need to be addressed at this level. The governors of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, along with local stakeholders need to formulate a regional strategy. This is unlikely to happen.[2] So what can New York City do to improve its own system? While expanding mass transit and reducing car ridership should be a priority, sadly, this is not likely to happen any time soon. Given the network we have, I offer here a proposal that will allow for a much more efficient system that will improve people’s lives.

The Mega-Network Philosophy

The first element is to recognize that New York’s transportation system is just that: one large mega-system or network tied together by means of travel and their routes. Transportation needs to be viewed broadly as an entire interconnected system—roads, highways, subways, commuter trains—and modes of travel—foot, bicycle, car, and train. All modes in New York are linked, directly or indirectly, by the relative costs and benefits of using each mode for a given objective. People frequently alternate between modes depending on the day, time, the nature of the journey, the availability of parking, how often the trains run, and so on. And yet, despite the overall flexibility that citizens have, the system is too easily gummed up. The reason is because the system is operated in a decentralized manner with each route-mode forced to fend for itself with little coordination and with little consideration of how they are tied together and impact each other.

Pricing

Once the entire system is viewed as a whole, the next step is then to use modern technology to operate the network as one large inter-connected system in order to allocate this finite resource in the most efficient manner as possible, in order to maximize the mobility of the people (and goods) moving about within it. The way to do this is to monitor all the elements simultaneously using big data computing methods to discover which route-modes are jammed up and which ones are operating smoothly (and how they may affect each other). Then the prices of using these different modes are changed throughout the day to improve efficiency. The entire system should operate to limit or make more expensive those things that cause the most congestion, while simultaneously encouraging those parts of the system that are underutilized or are operating smoothly. This means that transportation prices should be set according to the supply and demand for that mode at any given time.

While this might seem like a backhanded way of saying that tolls and fares should be increased, that’s not completely true. If a certain bus route is underutilized at the same time that a certain subway line is overutilized, prices should rise for the subway and fall for the bus. This means that some routes, say bus lines at a certain time of day, can be free or nearly free, while simultaneous with that, the rates of a parallel, but congested, route is relatively expensive.

Prices that Reflect Supply and Demand

This also means that all tunnels and bridges throughout the region need to have tolls and that these tolls should move up or down based on congestion levels. Instead of having a congestion pricing scheme for only lower Manhattan, all bridges and tunnels into Manhattan should have prices set based on how empty or full the city’s roads are at any given time. As more cars pour in, the fees for entering the island should start to spike.

The same applies to street parking. In Manhattan, 44% of the street area, on average, is used for on-street parking, and yet the prices people pay bear no relationship to supply or demand. On many streets, parking is free, and those streets with meters usually have low prices that are independent of how many people want to park on that street. The cost of parking needs to be more closely tied to both parking availability, and the impact of the cars on traffic congestion (not to mention CO2 emissions).

Information

In this day and age, the technology exists so that real-time pricing, and the costs and benefits of different means of travel can be instantly calculated and provided via website, mobile phone app, or on digital signs at bus and subway stops, and on road signs. Travelers would not only be charged based on the relative supply and demand, but just as importantly, they would have as much information as possible on what the costs and travel times will be, and they thus can make an informed decision.

During rush hour, people would choose the alternative that has the best benefit to cost ratio. Not in a rush? Take the cheaper but longer option. Have a meeting that you must attend? Take the quicker but more expensive option. Note that the different alternatives can have different cost-benefit ratios across days of the week and times of the day. There’s nothing inherent in the plan that would favor the wealthy over the poor, if each is free to choose the lowest-cost route. The point is to increase the efficiency of the movement of people by correctly pricing and allocating the different–but interconnected–parts of the network.

The Future

Data analysis can also reveal what the same trips or routes are likely to cost and their speeds in the near future, say 30 to 60 minutes ahead. If potential travelers know they could save both time and money by waiting an hour or so they might stay off the roads for a bit longer, thus freeing up the system for the current users.

Finally, since we are in the dawn of the age of self-driving cars, the pricing scheme offered here seems particularly well-suited for this coming transportation revolution. Autonomous vehicles can be directly tapped into the route pricing system and offer passengers different travel options based on the cost-speed trade-off. Implementing this plan now could make the transition to autonomous vehicles much smoother.

If you Can’t Make it Bigger, Make it Better

For too long, U.S. cities, like New York, have sat idly by while their transportation systems get older and more decrepit and continue to squeeze more and more people onto routes never designed for such volumes. Cities world over have expansion plans to match their growing populations. Yet for over half a century, New York has stubbornly refused to embrace its history of growing its network to match its growth. The gummed up and aging network reduces economic opportunities, wastes time and money, and stresses people out. If NIMBYism and political gridlock prevent us from having more transportation options, then we, at least, should utilize what we have more efficiently by correctly pricing the entire inter-connected transportation system. Think about that the next time you’re stuck in traffic or have to wait 30 minutes for your next (overcrowded) train.

—

[1] Not to mention that the area just outside the pricing zoning is going to face some severe parking problems, as people try to game the system to avoid the fee.

[2] For example, one of the first acts of New Jersey Governor Chris Christie in 2010 was to cancel a project to build a new badly-needed rail tunnel to Manhattan. Who knows if it will ever be built, despite the fact that the current tunnels are a century old and in bad need of repair. As another example, New Jersey was not included in the new Manhattan congestion plan and residents there are not happy about it;politicians are threatening some form of commuting-based fees as retaliation.