by Jason M. Barr September 5, 2018

[Author’s Note: This is Part I of a two-part Q&A interview with Professor Edward Glaeser. You can read Part II here.]

Edward Glaeser is the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics at Harvard University. He one of the world’s leading experts on the economics of cities. He is the author of Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier.

On Skyscraper Research in Economics

JB: While there are a handful of research papers in economics on investigating the causes and consequences of skyscrapers, such as by Helsley and Strange (2008) and Ahlfeldt and McMillen (2017), it seems that, by and large, even for urban economists, this topic is not a significant area of research. Do you think economists have ignored studying the economics of skyscrapers? And if yes, what kinds of research questions might be of interest to economists?

EG: I would go further and suggest that economists have spent too little time on the technology of building more broadly. Building technologies have shaped our cities and suburbs for centuries. They provide important sources of exogenous variation and are intrinsically interesting. For example, one of the unfortunate side effects of excessive land use controls is that building often occurs on a one-off basis. Mass production becomes impossible and there are large costs savings from building multiple units at once. Consequently, land use controls increase effective housing prices both by restricting the number of new units and by pushing construction into an inefficiently small scale. Perhaps, this helps explain why productivity advances have been so limited in construction in recent years. That weak productivity growth is itself an important topic for economic research.

Skyscrapers are themselves a particularly fascinating technology. The origin of the skyscraper is itself a fascinating story showing the ways in which ideas flit from sector to sector. I tend to give early credit to Joseph Paxton, the English gardener who had used metal frame structures for greenhouses. His inexpensive plan was chosen for the Crystal Palace exhibition in London and this then inspired Napoleon III and the French architect Victor Baltard. Baltard then used metal frames for Les Halles and for St. Augustine’s church in Paris. It would take another decade for William LeBaron Jenney to start using steel frame for a skyscraper: Chicago’s Home Insurance Building. Jenney performed the crucial combination of connecting metal frames with Otis’ safety elevators. His idea spread like wild fire in Chicago and was then adopted and improved by Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham and many others. This provides a classic model of how ideas spread across dense urban areas.

The skyscraper has two effects on the price of land. First, they allow more usable space on the same spot of land which should push land prices up. Second, they allow more usable space overall in the city which should push down the price of usable space and indirectly the price of land. One hypothesis is that rising urban land prices in the late 19th century were driven by the first effect, while declining land prices during the early 20th century were driven by the second effect. The connection between new building technologies and urban real estate cycles is a particularly pressing topic for future research.

On the Economics of Skyscrapers

JB: Do you have any thoughts about the debate about whether skyscrapers are economically too tall? The common perception is that the world’s (or region’s) tallest buildings are driven by the desire to claim an “ego-prize” (such as discussed in Helsley and Strange (2008)). Yet, in principal, one can think of a host of other rational reasons for excessive height—such as place-making or inducing agglomeration benefits by attracting high-skilled workers. How do you view this? And do you think “too tall” construction is good or bad for cities?

EG: I don’t have that much new to say about this question. The usual stylized fact is that building exhibits roughly constant returns to scale up to about 50 stories, but then costs rise dramatically after that point. This suggests that some skyscrapers (under 50 stories) are too short while others (over 100 stories) are too tall, except in conditions of extreme demand. I think both phenomena are worth more study.

The too small phenomenon is important for cities because if there is some force that artificially restrains the ability to build up, then the supply of usable space will be too small and prices will be too high. One candidate explanation for skyscrapers being too small is land use regulations. Yet developers often speak about their unwillingness to build up because of their limited appetite for risk. Credit restraints may also be important.

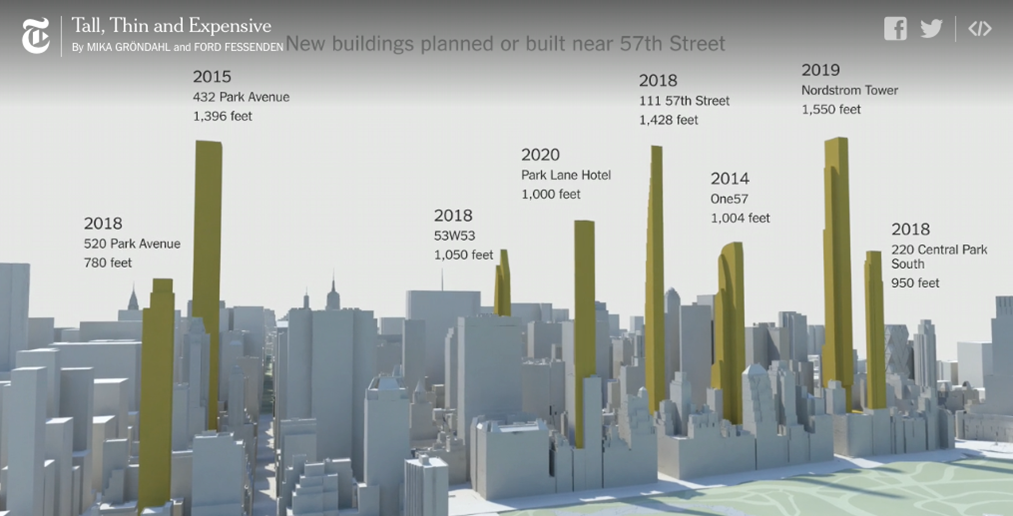

“Too tall” skyscrapers presumably reflect exaggerated expectations about future price growth, or the egos of their builders. Both phenomena were on display in New York’s great skyscraper race of the late 1920s. Both phenomena may also have been on display in Dubai a decade ago as well.

The issue of externalities from height is particularly fascinating. The original New York City zoning ordinance of 1916 was motivated by the excessive shadow allegedly cast by the Equitable Building on 120 Broadway. There are still complaints about shadows and views to this day. On the upside, large towers help agglomeration economies to flow and potentially reduce traffic congestion. A city in which people ride elevators and walk from tower to tower can be much more functional than a city that is mired in cars.

On Luxury Highrise Apartment Buildings and Regulations

JB: One of the vigorous current debates about tall building construction is regarding supertall luxury apartment buildings in places like New York, San Francisco, London, and Vancouver. Detractors argue they exacerbate gentrification and income inequality, while harming the quality of street life, and throwing shadows on the street and in parks. What is your view of the effect of tall luxury apartment buildings on cities? Should they be taxed or regulated? Or should they be encouraged?

EG: I think that the starting point has to be a serious quantification of the externalities that I just mentioned. Almost none of the land use regulations that cities have ardently adopted for over a century have been justified by any serious quantitative work. The existence of even the smallest externality, such as a shadow, has been seen as justification for massive interventions in the housing market.

My own belief is that we have almost surely limited skywards construction excessively in our most successful cities. I think that the externalities from height are real, but that they are overwhelmed by the pure economic benefit of building, which can be quantified by comparing construction costs with the current price of usable spice. More than a decade ago, I estimated that the cost of building another story (which is the marginal cost of extra space) was less than one half of the market value of that space in Manhattan. Prices are even higher today. I can’t imagine that the negative externalities from building are anywhere near high enough to justify such a massive implicit tax.

One of the reasons to be skeptical about these negative externalities is that if people don’t live in an urban skyscraper, they will live somewhere else, and there are also externalities from other forms of building. Suburban homes lead to more driving which generates congestion and pollution externalities. Restricting construction in America’s more temperate cities, which include Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles, induces more construction in hotter places like Houston. The impact of that rerouting of construction is more air conditioning and more carbon use.

On NIMBYism

JB: One of the main arguments in Chapter 6 of Triumph of the City is that landmarking, historic preservation, and zoning are driving higher housing prices, and that places like Paris and New York should allow residential building height to increase according to the demand. But this raises several important questions. How can a city realistically make such a plan? It seems that nearly every large city in the West is prevented from allowing the housing market to operate more closely to match supply with demand for all income brackets. What might be some realistic ways that governments can prevent the NIMBYists from vetoing housing market reform? Do you see any good examples of denser older cities that have been able to overcome the NIMBY problem?

EG: I think that there are two reasonable political paths against NIMBYism. The first is top down. Strong mayors often like building up, because of the construction jobs, property tax revenues and agglomeration effects. Consequently, leaders like Michael Bloomberg, Richard Daley and Boston’s Marty Walsh have all fought for more permissive construction environments. Generally, the smaller the jurisdiction, the less likely will political leadership see the upside in construction. Part of the problem is that restrictions benefit current home owners at the expense of prospective external resident, and the smaller the jurisdiction the larger this problem will be.

The second path is the new YIMBY movement, which is a ground up swell supporting new development. In a sense, that movement recognizes that incumbents, typically an older generation, has enriched itself through land use regulations at the expense of a younger generation. We have yet to see the YIMBYists achieve significant change, but the movement is a really welcome addition in urban political discourse.

In terms of policies, the question becomes what level of polity is implementing the change. At the local level, the easiest change is just to allow more as-of-right high-rise building rules. As-of-right means less regulatory uncertainty. If there are real externalities, we can certainly impose impact fees, but these should be a replacement for a lengthy permitting process.

At the state level, the government needs to encourage lower levels of government to permit more housing. One approach, typified by Massachusetts, Chapter 40B is just to over-rule local land use controls and impose a more permissive state level building code. A second approach, since in New Jersey’s post-Mt. Laurel system or Massachusetts 40R or 40S, is to provide financial incentives for localities to encourage more building. State transfers, for example, could be tied to the level of local building.

***

[Continue reading part two here.]