Jason M. Barr January 14, 2020

Note: This post is one of several about New York City. More posts can be read here.

Costanza versus the Andria Doria

In Season 8, Episode 10 of Seinfeld (“The Andrea Doria“), George Costanza, the neurotic buddy of Jerry Seinfeld, has found a fantastic Manhattan two-bedroom apartment with a huge bathroom and walk-in closet. The only rub—there’s competition for the unit. An older man who lives upstairs also wants it. He was a survivor on the ocean liner, The Andria Doria, which, in 1956, was struck by another vessel and sank off the coast of Nantucket, killing 51 people. The building’s tenant association feels pity and wants him to have the apartment.

But George, being George, is not above suppressing his dignity to get what he wants. He attempts to sway the association’s members by recounting his pathetic life story and his innumerable sufferings, or as Jerry calls them, “The Astonishing Tales of Costanza.” While we don’t know if he gets the apartment, the show ends on a hopeful note—his tales of woe were far superior to his rival, who was “merely” rescued by a lifeboat.

While Costanza’s dilemma is, of course, fiction, it’s funny because it rings true. The episode’s comedy is premised on the notion that the right to live in Manhattan is based on some form of housing gladiatorial competition—one person wins, and the other loses. The city’s real estate is a zero-sum game. But, do the tragicomedies about our lives really need to be about finding affordable housing? Perhaps we should take a step back and think about the problem from a different light?

If Apartments were Like Milk

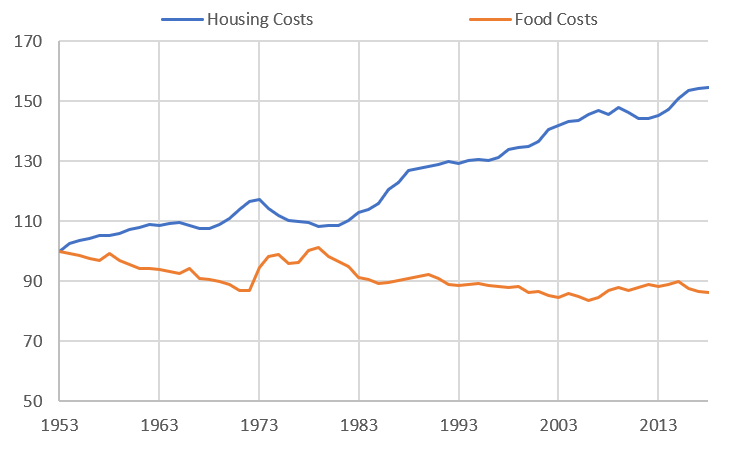

For most things in life, we take it for granted that they will be available if we want to buy them. Nearly all the time, there’s milk at the store, and, in general, milk prices remain steady over the long run. In fact, inflation-adjusted milk prices have fallen by about one dollar per gallon since 1995. At the risk of repeating myself: milk today is about 25% cheaper than it was a quarter-century ago. Can you say that about your housing?

The reason that milk prices remain reasonable is that there is more milk available at any one time than consumers want to buy. You go to the store, and it’s plenty stocked. You can even say there’s nearly always milk “vacancy”–the many containers just sitting there waiting to be purchased. It’s only when the excess supply begins to shrink relative to demand that prices rise.

To take an extreme example, right after Hurricane Sandy wiped out local refineries in late 2012, the Governor of New Jersey implemented gasoline rationing for about ten days. His purpose was to keep prices artificially low for the short-run since gasoline “vacancy” would have been negative. That is, the amount of gasoline available would have been far less than what consumers wanted to buy—and prices would have spiked as a result. Once the refineries were back online, things went back to normal. The same principle works for housing. If housing is to be affordable at all income levels, there must be many more units available than the demand at a given time. It’s that simple.

Blaming the Messenger

Somehow people see rising prices in cities like New York and blame landlords, or they see “greedy” developers building supertall luxury towers and blame them for gentrification. As a result, they turn to the city government to curb developers from increasing the housing supply. Simply put, they blame the messenger and not the restrictions that the residents themselves have required. But, the more limits in the housing market, the higher are housing prices. If people want affordable housing, they should insist upon more construction. If milk were like apartments, we’d all be very thirsty indeed.

Vacancy in New York City

Since 1943, New York City has had some form of price controls in its housing market. Today, the most important is rent stabilization. Landlords who own units subject to this program are limited to increasing their rents to specific percentages fixed by the Rent Guidelines Board. For October 2019 to September 2020, building owners can only raise rents by 1.5% for one-year renewals and 2.5% for two-year renewals.

Under the law, the Rent Stabilization Program stays in effect if citywide rental vacancies remain below 5%. But the perverse incentives for new construction created by the program means vacancy rates remain low, maintaining the program indefinitely. If there was ever such a thing as a perpetual-motion machine, this comes close. In terms of rental apartments, about 57% of them in New York are regulated in some way—and two-thirds of residents are renters.

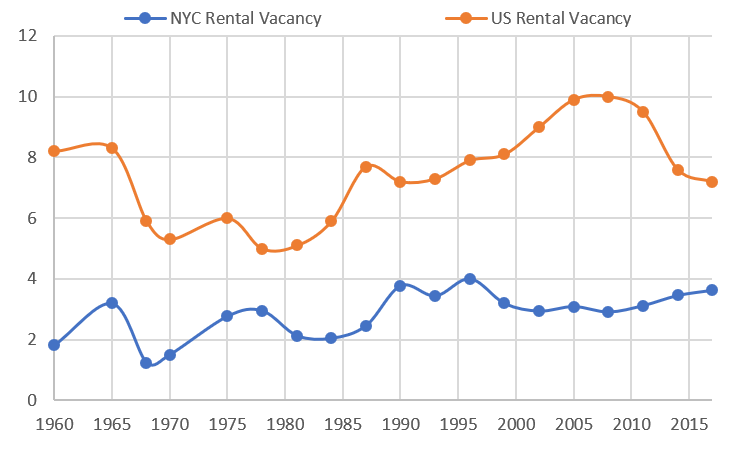

Citywide Vacancy

The Board’s latest report, issued in May 2019, should give us pause. The citywide rental housing vacancy rate was 3.63% in 2017, which compares quite unfavorably with the national rate of about 7.2%. But the citywide rate is misleading. The biggest problem is among those units which are rent-stabilized. Vacancy in pre-War stabilized units is only 2.4%, and in post-War stabilized units, it is only 1.2%. Free-market units have a vacancy rate of 6.07%, closer to the national average. In a city of over eight million people, there were only about 20,000 free units in rent-stabilized apartments in 2017. If these units had the same vacancy rate as the free-market ones, that would have been an additional 38,700 units to choose from. If those apartments had the same vacancy rate as the national average, then that number would rise to nearly 50,000 more units.

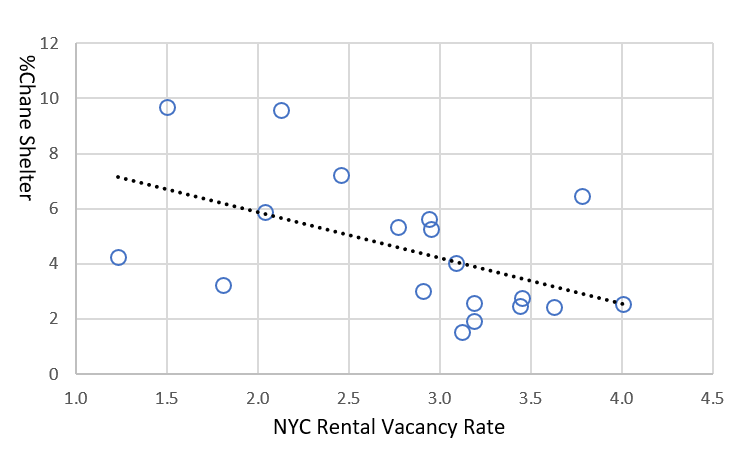

Elements of Vacancy

Just as important is affordability. The law of supply works for housing just as it does for milk: the more units brought to the market, holding demand constant, the lower the prices. As I will discuss below, there’s a strong negative relationship between the number of vacant units and the cost of housing in New York City. And the finding strongly suggests that New York is harming itself by over-regulating its housing market.

Of course, before we can make this conclusion, we must ask what drives housing to be vacant—both rental and owner-occupied units. To begin, let’s divide the discussion into two modes—what I call the upswing and the downswing. The upswing is when the community or city is doing well. Employment is high, the neighborhood is attractive, and all is normal with the world. The downswing is times when either the neighborhood is in bad shape due to some local problems or when, more broadly, the economy is doing poorly.

The Upswing

What causes vacancy during the upswing? First is simple: “churning.” People come and go, and some units are empty until they find new occupants. Another reason is construction. When a new building is erected, it takes time to fill it up. Ideally, a developer would like to have contracts signed on all apartments the day the doors open, but that’s not always the case. Lastly, vacancy during the upswing can be caused by a kind of “hold out” issue.

In many situations, a developer buys a building with tenants, and, over time, gets them to move out so she can tear it down or completely renovate it. Here, she is removing units from the market. In the first two cases, we would expect a neighborhood with higher vacancy rates to have lower prices. In the third case, the reverse is true if there are fewer opportunities for residents. As long as the first two cases dominate the second, more vacancy means more lower prices.

The Downswing

During the downswing, vacancy would mostly be driven by people moving out—either the neighborhood has fallen on hard times, or the economy is in bad shape, and people are exiting the city in search of opportunities elsewhere. Or the landlord finds that she can’t rent units at a price that pays for the costs and lets them fall into disrepair. At any rate, this means that prices are likely to be low regardless of vacancy because it’s a low-demand area.

Vacancy and Housing Prices in New York City

If, on average, housing vacancy represents an “oversupply” of units, then the question we’d like to know is how does this additional housing affect the market prices especially during the upswing? Presumably if there are extra units available, consumers have more choices and they can then get lower prices. But this discussion raises two points about measurement. First is that we can’t simply look at the raw correlations between neighborhood vacancy rates and housing prices—though, on net, across New York City they are negative. It’s necessary to control for neighborhood, building characteristics, and citywide growth, to more accurately measure vacancy’s impact on housing prices. To solve this problem, I have collected data on several important building and neighborhood characteristics to better isolate the impact of vacancy.

The second problem relates to the direction of causality. When a unit is vacant it may be because price changes are driving the decision to leave the unit empty. In the upswing case, the landlord might be taking units off the market until she can tear down the structure, or completely refurbish them. In the downswing case, the landlord might decide to stop maintaining the unit because rents are too low. But, our interest in looking at how vacancy affects prices, not how prices affect vacancy. To get at this issue, I look at vacancy rates at different geographic levels. First is within small areas around each building (that is, at the census tract level), and second is an average of vacancy rates outside the census tract.

The key point here is that, in principle, we don’t care what causes the vacancy rates in surrounding neighborhoods, but we are interested in whether, on net, they spillover to prices in a given neighborhood. That is to say, in theory, the vacancy rates in surrounding neighborhoods are exogenous with respect to the prices of housing in any given neighborhood. Additionally, I was able to get data on why the units are empty (such as being on the market or sold but unoccupied). This allows me to control for units that might be unavailable for residents to choose from when they are looking for a new place to live.

The Results

Using the statistical method of regression analyses (details here), I investigate the determinants of the sales prices of over 40,000 residential building in 2016 and 2017 across New York City. In particular, I’m interested in isolating the impact of the number of vacant units in a census tract and surrounding tracts on the prices of individual building sales. Note that I do not have data on apartment rents or the sale of condo and coop units. Since rents determine the sale prices of rental buildings, I implicitly measure the impact of vacancy on rents for these buildings.

The findings are robust and strong: across the city, a 10% increase in the number of vacant units in surrounding neighborhoods, reduces the sales price of a residential building by about 6-7%, on average. Within census tracts, a 10% increase in vacant units reduces prices by about 0.2-0.3% on average. The results also apply to the poorest neighborhoods—those with median incomes in the lowest 25th percentile. The findings suggest that new construction throughout the city helps everyone, though the impacts likely decline with the distance from that construction.[1]

How Come We Can’t See It?

But if vacancy—primarily through new construction—is good for affordability, how come people can’t see it? The answer is that over time the demand to live and work in New York is increasing. As a result, average prices are rising faster than new construction. Any benefit from a high vacancy rate is often “suppressed” by price increases more broadly. From 2016 to 2017, average citywide prices grew by over 14%.

To have any “bite,” vacancy across the city must outpace demand–only then will residents begin to feel its benefits. This means the city must undertake substantial new construction–way beyond anything being done now. In 2017, for example, New York City added nearly 26,000 units of new housing. But in a total stock of 3.54 million units, this new housing represents less than 0.1% of additional homes (and does not count demolished units). This is why housing in New York is so expensive.

A Way Forward?

I want to stress, however, that rent regulations are not the only thing preventing new construction in New York City. There are several forces at work. First is, of course, rent stabilization, which gives tenants a good deal and the right of first refusal on lease renewals. These keep people from moving out of these buildings, and so they are effectively removed from being torn down and replaced by denser buildings. But just as important are zoning policies, which limits how much can be constructed in each neighborhood across the city. As I have discussed elsewhere, nearly 50% of the residential land in New York is reserved only for one- and two-family homes. Allowing these neighborhoods to densify to low- and medium-rise apartments, for example, would help affordability significantly. Finally is the cost of construction. New York has some of the highest costs in the nation, which is a big disincentive to adding to the housing stock.

The Political Economy

But perhaps the biggest problem is the political economy of the issue: the coalition of anti-new-housing in the city remains strong. Several groups (ostensibly) benefit from stringent regulations that limit new construction citywide—and they make up the majority of residents.[2] First are those in regulated units who are unwilling to give up that perk. Second are homeowners who seek to limit construction for fear that it will lower their property values. Third are preservationists and anti-gentrificationists, who feel that any new construction destroys the feel of the streets, removes beloved architecture, and promotes luxury apartments for billionaires.

All these residents are individually rational, as the benefits to them of new construction are uncertain and long term, and with significant disruption in the meantime. Collectively, however, they are helping to contribute to rising prices citywide. As I have discussed elsewhere, there are policies that can help balance the needs of today’s residents with the health and well-being of the future–affordable–city. But this takes enlightened and forward-thinking leadership. That’s a harder problem to solve.

Continue reading other posts about New York City here.

—

[1] Lerbs and Teske (2016) find a negative relationship between prices and vacancy in German cities. Hsueh, Teng and Hsieh (2007) find this relationship across Taiwan.

[2] Regulated units in New York comprise 39% of housing units. Owned homes (free standing homes, condos, and coops) are another 32% of units. Source: Housing Supply Report (2019).

[…] Take New York City as an example. The city’s FAR-based regulations were enacted in 1961. They were designed to reduce density as compared to the 1916 zoning codes, which were seen as not being restrictive enough. While small FAR changes (rezonings) in different neighborhoods occur from time to time, there has been no systematic change in the regulations in over half a century. In other words, the same FAR codes, more or less, are in effect today as when John F. Kennedy was President and when The Andy Griffith Show was one of the most popular TV shows in the nation. (If you’re young enough not to know what I’m talking about then I think I’ve made my point.) Once FAR regulations are imposed, they are nearly impossible to dislodge, despite mounting evidence that they are harming the city. […]