Jason M. Barr August 9, 2018

[Author’s note: This is the first of at least two blog posts on Jane Jacobs and her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961.]

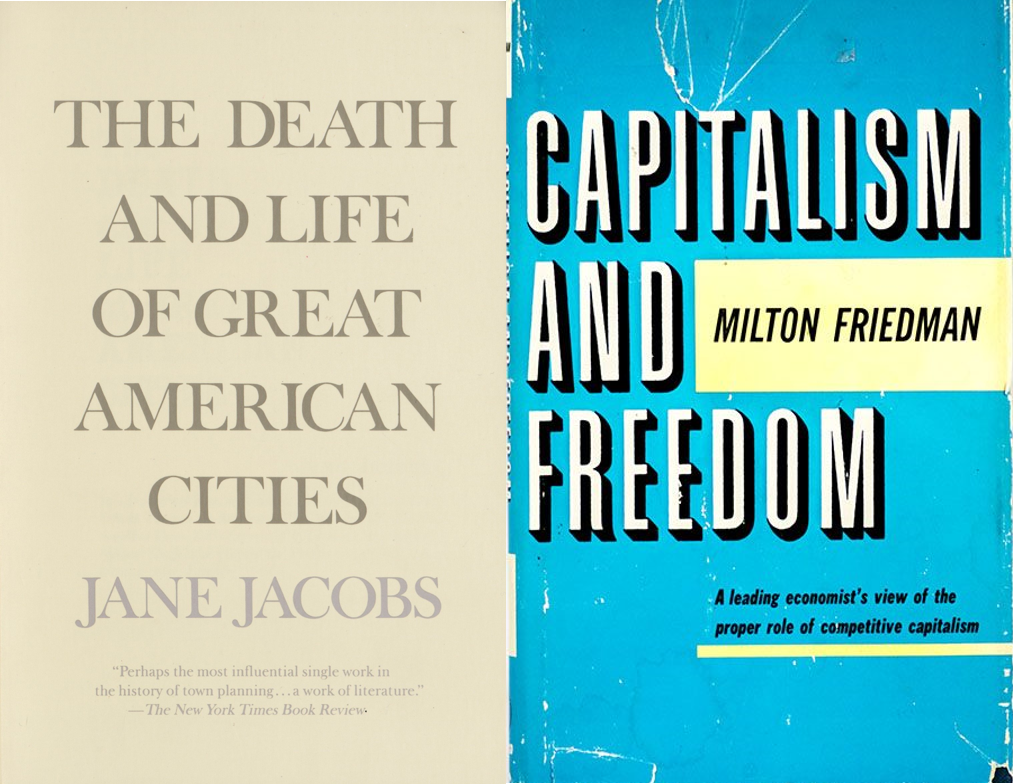

With the resurgence of large cities like New York, San Francisco, Boston, and Chicago, it’s hard to imagine that not too long ago America’s cities were falling apart at the seams. In 1961, Jane Jacobs published her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, as an attempt to diagnose the problems and offer solutions.

Today, Jacobs is revered among urbanists. She was a visionary—able to see—what others could not—the elements of urban form and economics that were critical. Since then “Saint Jane” has been the Patron Saint of Livable Cities. If we take a step back, however, her ideas suggest a strong connection with those of libertarianism, the economic philosophy espousing the elimination of government from as many areas of economic and social life as possible.[1]

Government of Big Ideas

First to note is that the title of her book begins with the “Death.” In no uncertain terms, she blames government for this “urbanicide.” Misguided officials and planners were blindly seduced by 19th and early 20th century urban thinkers. Reformers, such as Ebenezer Howard and Jacob Riis, saw industrial cities as overcrowded hives of poverty, vice, and disease. They argued for the need to scatter the working classes into wholesome “garden cities,” freed from corruption and debasement. In the 1920s, French architect Le Corbusier embraced this perspective, but applied a modernist twist. Buildings were machines for living and should be arranged in a planned and efficient manner. City dwellers should occupy highrise towers surrounded by open space (surrounded by highway belts).

Believing these ideas were paths to better living, government officials created grand schemes of urban renewal, slum clearance, and tower-in-the-park public housing. They built massive highway systems to generate sprawling suburbs. America, after World War II, was a time of big government ideas. The nation, through governmental direction, combined with American ingenuity and pluck, defeated Nazi Germany and the other Axis powers. The New Deal helped relieve millions from poverty and spurred economic growth. Though rejecting outright Socialism, American governments saw their roles as being able to actively direct human energies for the betterment of society.

Libertarianism

But, there were those who rejected those ideas. Among them was the Nobel prizing winning economist, Milton Friedman, arguably the Patron Saint of Modern Libertarianism. He wrote and spoke widely against government interventions. He argued that programs of “big ideas” designed to help society, where, in fact, doing the opposite. They frequently generated unintended consequences, while limiting human freedom. Jacobs’ book, written at about the same time as Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom (1962), espouses the same philosophy.

Jacobs or Friedman: You Decide

When you read their writings, they frequently sound alike. Here are a few quotes from each. Try to guess who is Jacobs and who is Friedman. Note that all Jacobs’ quotes are from Death and Life, while Friedman’s quotes are from Capitalism and Freedom.

On Public Housing

Far from improving the housing of the poor, as its proponents expected, public housing has done just the reverse. The number of dwelling units destroyed in the course of erecting public housing projects has been far larger than the number of new dwelling units constructed….But this has only made the problem for the rest all the worse, since the average density of all together went up.

***

Public housing on its part is held to a current cost of $17,000 per dwelling unit. Were the involuntary subsides absorbed as public cost, the expense of these dwellings would soar to politically unrealistic levels. Both of these operations, “renewal” projects and public housing projects, with their wholesale destruction, are inherently wasteful ways of rebuilding cities, and in comparison with their full costs make pathetic contributions to city values.…. Project building as a form of city transformation makes no more sense financially than it does socially.

On the Paternalism of Government

Conventional planning approaches to slums and slum dwellers are thoroughly paternalistic. The trouble with paternalists is that they want to make impossibly profound changes, and they choose impossibly superficial means for doing so. To overcome slums, we must regard slum dwellers as people capable of understanding and acting upon their own self-interests, which they certainly are.

***

Public housing cannot therefore be justified on the grounds either of neighborhood effects or of helping poor families. It can be justified, if at all, only on grounds of paternalism; that the families being helped “need” housing more than they “need” other things but would themselves either not agree or would spend the money unwisely.

On Order from Freedom

The possibility of co-ordination through voluntary co-operation rests on the elementary—yet frequently denied—proposition that both parties to an economic transaction benefit from it, provided the transaction is bi-laterally voluntary and informed….Exchange can therefore bring about co-ordination without coercion. (Emphasis in the original.)

***

Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city….This order is all composed of movement and change….an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole.

For quotes identifications click here.

Planning

It’s likely Jane Jacobs would not have called herself a libertarian, and, in many respects, her focus and interests were different. Libertarians are mostly interested in economy-wide issues, such as monetary policy, drug and prostitution legalization, and the private sector provision of public goods, such as roads and schools. Jacobs was much more concerned with the health and well-being of cities—of what creates vibrant places to live, work, and play, especially for the middle and lower classes. However, her worldview was similar, and she occasionally made common cause with them.

First, like libertarians, she wanted to eliminate government “planning,” where “planning” related more narrowly to slum clearance, urban renewal, public housing, and massive highways placed in the heart of cities; whereas libertarians use the world broadly to refer to nearly any control of economic activity by governments.

Government’s Role

Jacobs and Friedman shared the belief that the proper role of government is to establish the institutional framework—or superstructure—that allows individuals to maximize their well-being. Jacobs’ personal interest was that individuals were free to pursue their own self-interest in regard to geography.

She argued that neighborhoods should never have only residents, or factories, or bars, or offices. Good neighborhoods had all of these things side by side. Governments in the quixotic quest to improve quality of life have “sanitized” neighborhoods by imposing single uses. In the process, they eradicated the economic elements needed for urban vibrancy. The cure was worse than the disease.

The key to this freedom was economic and social diversity. A competitive and diverse landscape best balanced anonymity with social cohesion. It gave residents access to a wider variety of goods and services; the freedom to join clubs or associations (or not); and freedom from crime and fear.

Jacobs’ Economy

Jacobs’ insight was to identify four key elements that a neighborhood needs to be successful:

- There must be a diversity of functions—places where people work, live, shop, and play—all in the same place.

- Blocks need to be short, with the opportunity to turn corners frequently; sidewalks need to be as wide as possible.

- There must be a variety in the age and condition of buildings.

- There must be a dense concentration of people, including densely occupied residences.

The role of government was to create set the stage for the “dancers,” but beyond that, the rest was to be improvised by the residents themselves.

Jacobs’ Prescriptions

But unlike modern libertarians, Jacobs did not see a diverse local market as inherently stable (and she would likely have been against supertall skyscrapers for the mega-wealthy). Neighborhoods that become too popular would then see less profitable—but vital—uses crowded out, tipping the neighborhoods toward monoculture. However, her policy prescriptions are indeed quite limited. In her book, she essentially offers only four.

Blocks and Sidewalks

First, long city blocks should be divided into shorter ones over time, as the ability to do this arises. For example, if a few buildings in the middle of the block are torn down or abandoned, the city should buy the properties and make them streets. Furthermore, all sidewalks should be extend far out in to the street to encourage as much activity on the sidewalk as possible.

Subsidize Dwellings

Jacobs felt strongly about keeping the government out the housing market. But in cases where the free market did not generate enough low income housing, programs could help. Her suggestion was that first government provides construction loans or loan guarantees. Second was to ensure to these builders a minimum rental earning for the property.

In exchange, the landlord would be required to accept only tenants who already lived in the neighborhood without regard to income or ability to pay. Only after the tenants were selected was the landlord allowed to see a renter’s incomes. If it was too low to pay, the landlord would then receive the difference between the a reasonable return and what the renter could afford to pay. The idea sounds a lot like housing vouchers, a program widely favored by free-marketeers.

Zoning

Jacobs’ conception of zoning was different than current zoning rules, which mostly continues to promote the separation of usages. She wanted zoning that did exactly the opposite—that encouraged diversity, where apartment buildings were next to restaurants and bars, factories, shops, and cultural institutions. To prevent the tipping toward homogeneity, Jacobs advocated for rules that prohibited any one type of business from occupying too much building area.

As well, she believed that neighborhoods should have buildings of a variety of ages, from very old to brand new and everything in between. Diversity of ages promote diversity of uses and users. As a result, she suggested some possibilities—landmarking old buildings or limiting the heights of new buildings.

Better Living through Diversity

The efficacy of these policies for both her aims and for cities more broadly will be left for a future post.[2] But suffice it say, that was basically it from her on government interventions. She was eager to see limited government in the life of neighborhoods. She vociferously argued to let the people decide their own actions, and from the seeming chaos of the dense city, the ordered and well-balanced life would naturally emerge.

The question remains, however: How have people taken her advice over the years? Is it possible that her words gave rise to the opposite of what she wanted? In the next post, I take up the issue of whether Saint Jane has also become the accidental Patron Saint of NIMBYism.

——-

[1] I would like to stress that the ideas and beliefs presented here on libertarianism and “Jane Jacobism,” do not necessarily follow my own.

[2] If I had to guess, Milton Friedman would have been indifferent about her policy on blocks and sidewalks; would have supported housing vouchers; and would have been against her zoning ideas, since they limited property rights.

[…] the 1960s, with the publication of Jane Jacob’s book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and the failures of public housing, slum […]