Jason M. Barr and Remi Jedwab May 9, 2023

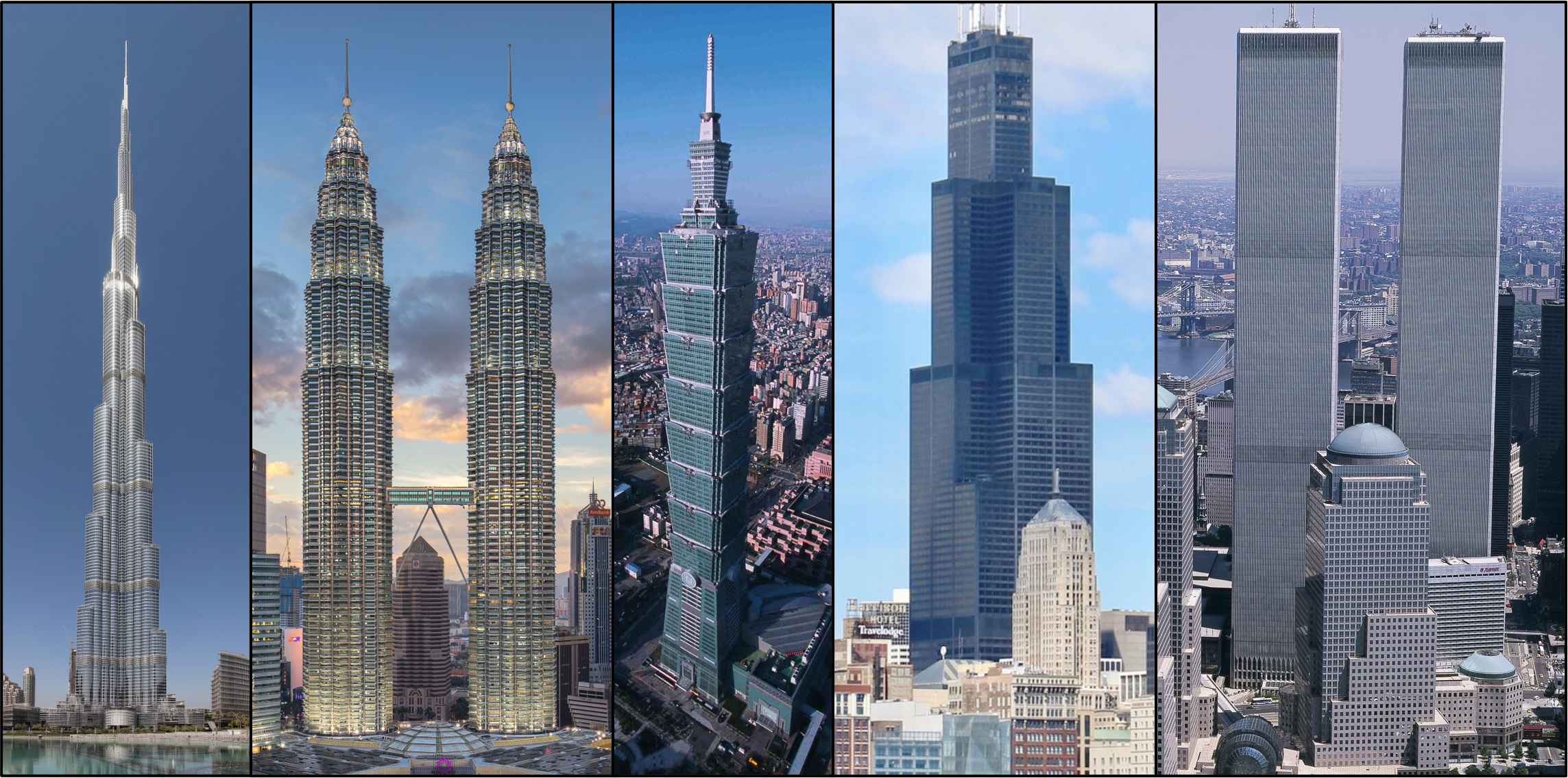

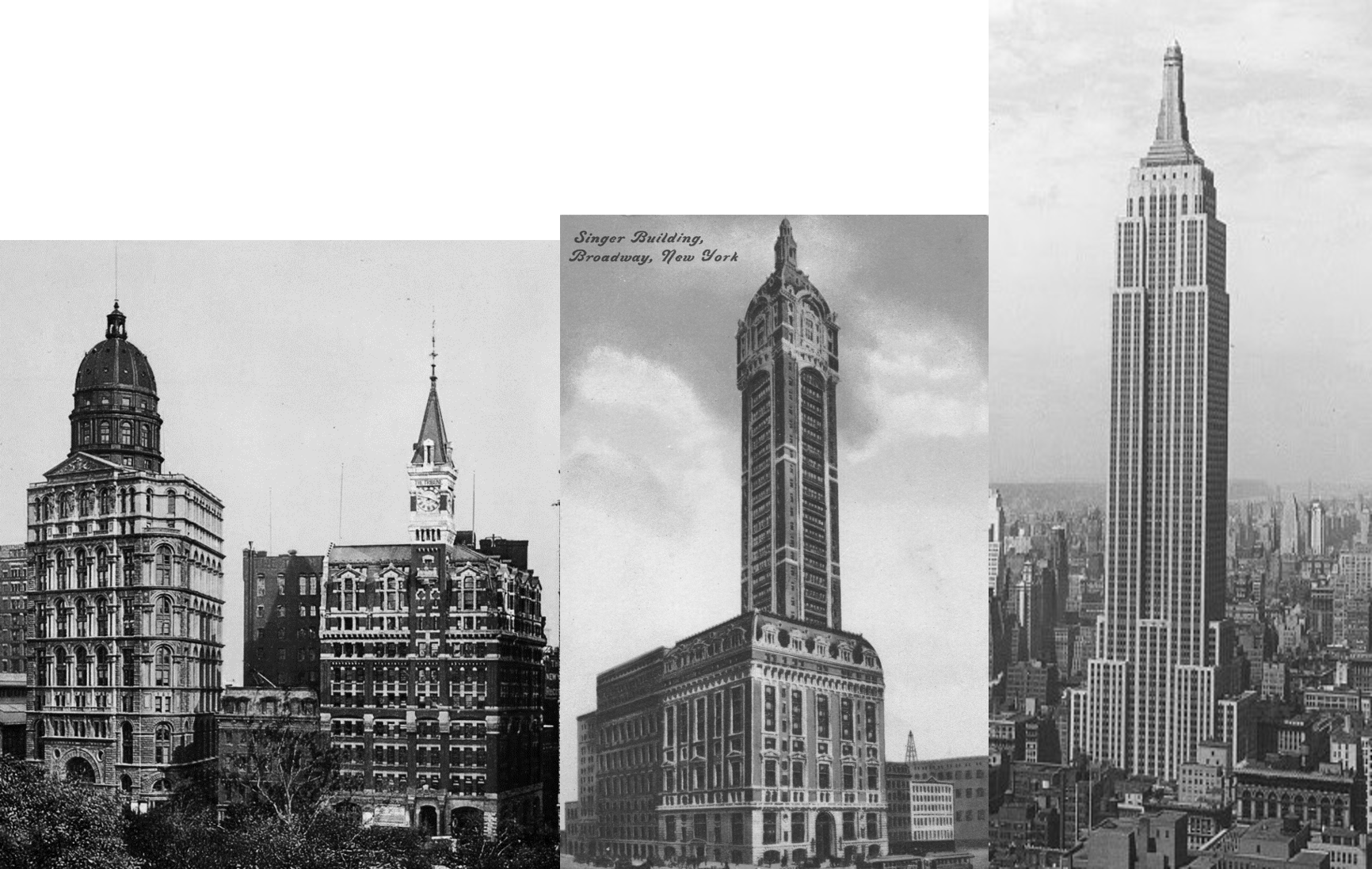

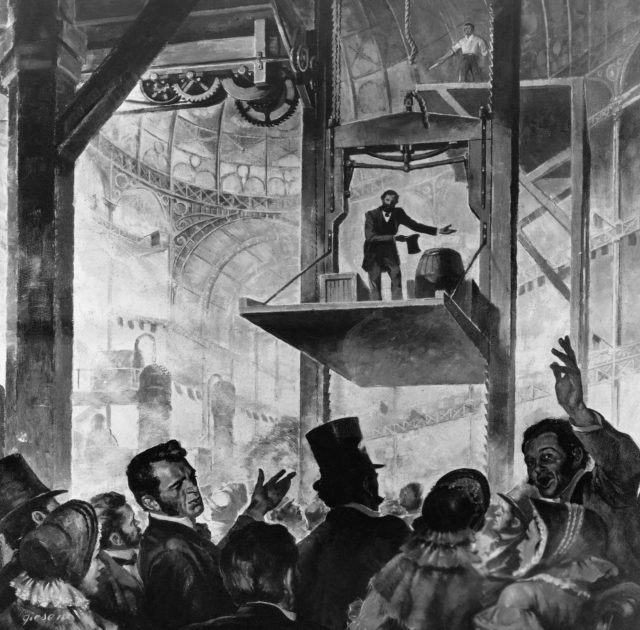

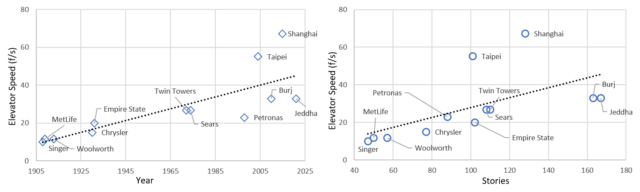

When we think of skyscrapers, we think of the tales of ego-drenched developers engaging in height competitions to claim the prize of “tallest building.” We recall the three-way height race during the Roaring Twenties between the Chrysler Building, the Bank of Manhattan Building, and the Empire State Building.

But despite the tendency to telescope on supertalls and record breakers, they are–statistically speaking–rare. The world record has been broken only 12 times since 1890 and only twice in the 21st century. Hardly a perennial gladiator competition.

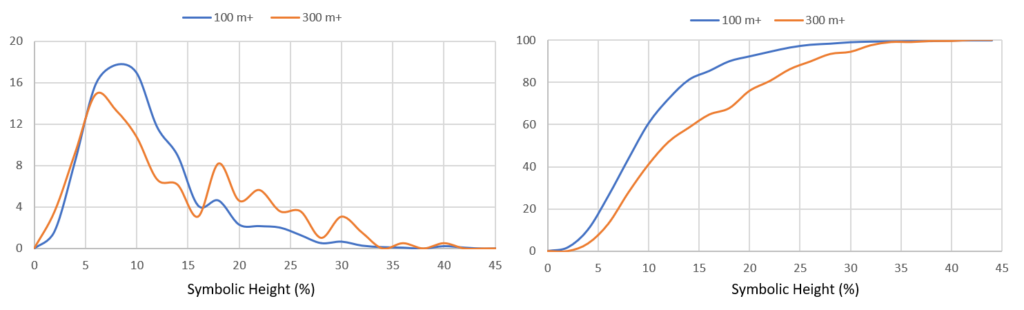

For that matter, there are over 44,000 buildings around the world that are 100 meters (~25 floors) or taller. Of those, two out of three are shorter than 132 meters (~34 stories); and 90% are shorter than 170 meters. If you use 55 meters (~14 stories) as a cut-off, 83% are less than 100 meters. In short, the vast majority of the world’s tall buildings are between 14 and 30 stories.

Measuring Skyscraperness

And where are these buildings distributed across the planet? To most people, the answer is obvious. China, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates are the clear winners. Hong Kong is the ultimate skyscraper city. New York and Chicago started the Skyscraper Revolution at the end of the 19th century. And Dubai, with the Burj Khalifa, is the world’s “Blingiest City” –Vegas-on-the-Gulf.

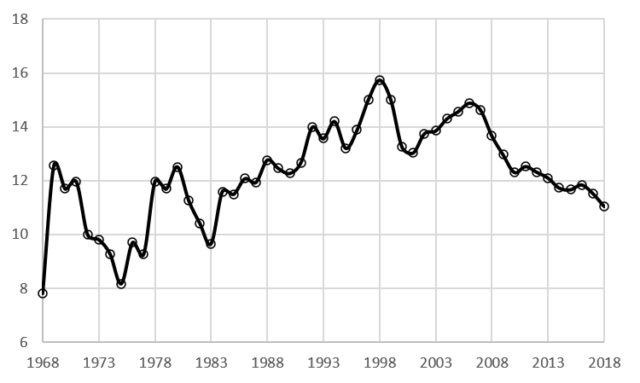

But how much do our perceptions capture what is happening globally? Rich and urbanized countries tend to have more skyscrapers because the economic conditions would favor them. In urban centers where land values are the greatest, developers are incentivized to build tall to make “the land pay.” Businesses prefer to be in their downtown clusters, while residents are eager to live in high-rise apartments near work, amenities, and fun.

So, the strong correlation between an economy’s urbanization and gross domestic product (GDP) and the heights of its tall buildings does not say much about which countries are more pro tall than others. New York, Hong Kong, and Dubai are among the world’s wealthiest cities, so the underlying economics would suggest they “should” have more tall buildings.

Thus, we need to measure the degree to which cities and countries build up, not because of the size of their respective economies but rather despite it.

Countries and Skyscrapers

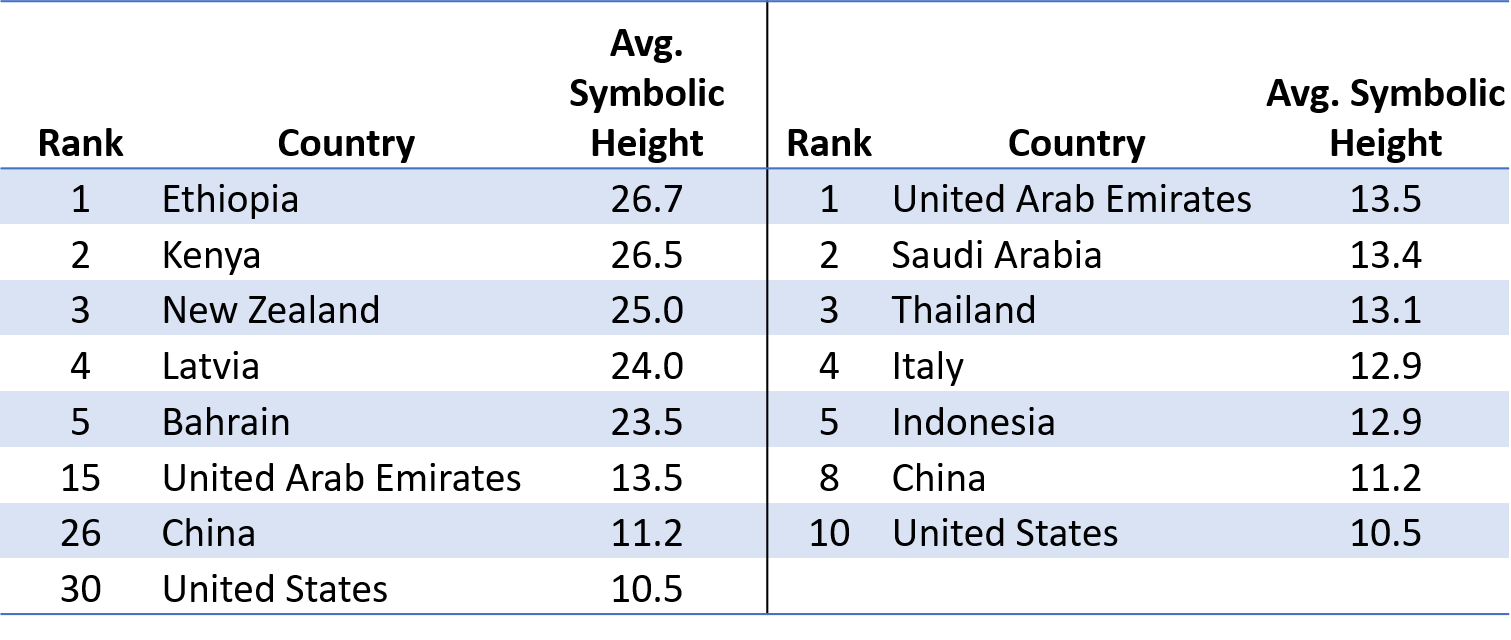

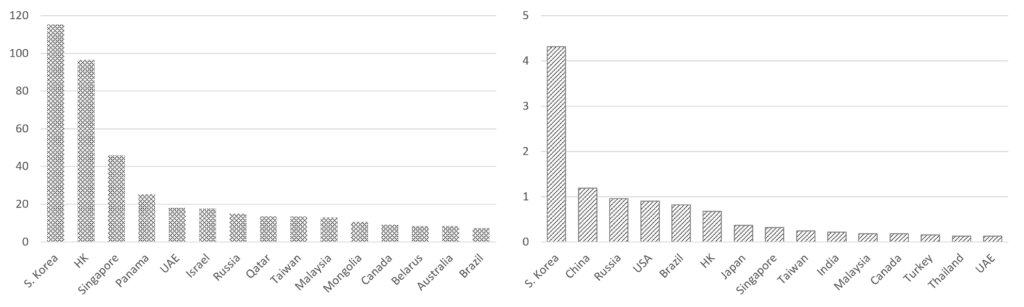

To answer these questions, we have investigated a data set containing nearly all the world’s buildings that are 55 meters or taller.[1] As a first, raw measure of “skyscraperness,” we added up the total heights of all these buildings for each country and divided them by their respective urban populations. This gives the number of kilometers of building height per million urban residents.

When we do this, the densest tall building country is, in fact, South Korea, with Hong Kong second. Singapore, Panama, and the United Arab Emirates come in third, fourth, and fifth, respectively. (The full rankings are here).

The result of this exercise is that the countries that contain the most “exciting” skylines are not necessarily the highest ranked. South Korea “wins” because it focuses on high-rises rather than skyscrapers, though it does have one supertall, the Lotte World Tower at 123 stories, the 5th tallest building in the world.

Where is the United States? It’s ranked 19th. The reason is that while New York and Chicago do much of the “heavy lifting,” most cities house their populations in one-family homes. Simultaneously, suburban office parks are just as common, if not more so, than central city office skyscrapers. States like California and Texas are like countries on their own, but their cities have relatively few tall buildings.

Mainland China ranks 43. Ironically, despite China’s love of tall buildings, the data suggest that it does not “overbuild” relative to its urban population.

A Skyscraper Index

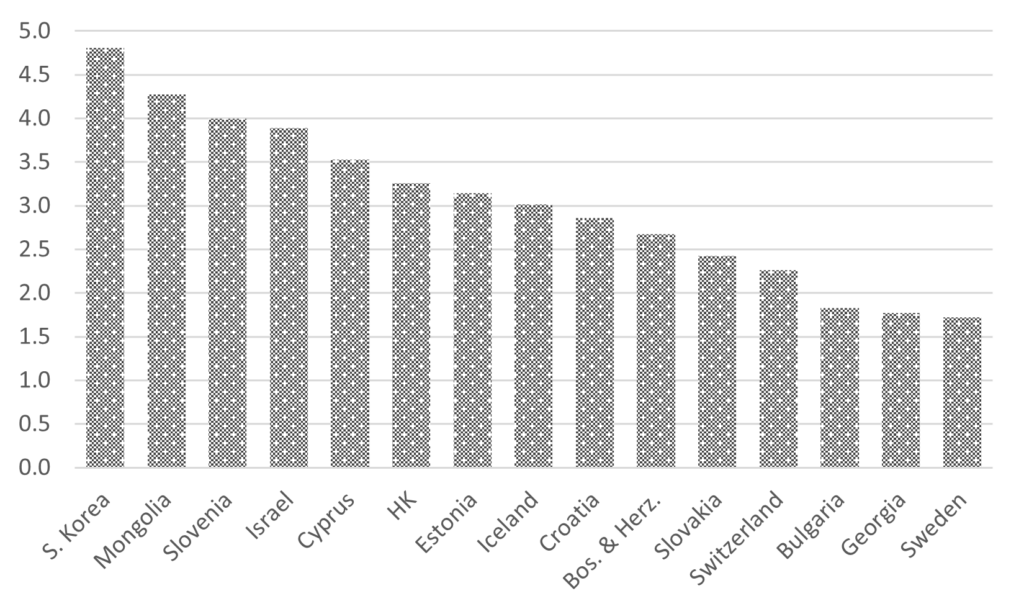

But again, this may not be the right measure. A better indicator is to create an index of skyscraperness based on how much cities build up after controlling for their population, income, and other factors that might directly affect their supply.

The result of this exercise—what we call the Skyline Index—preserves South Korea’s top ranking, but, after that, the rankings change quite a bit. In fact, the second most “tall building” nation is Mongolia, followed by Slovenia and Israel. These countries have more tall buildings than they “should,” given the size of their economies. The big players, like China, the UAE, Hong Kong, and the United States, are nowhere to be found.

By Region

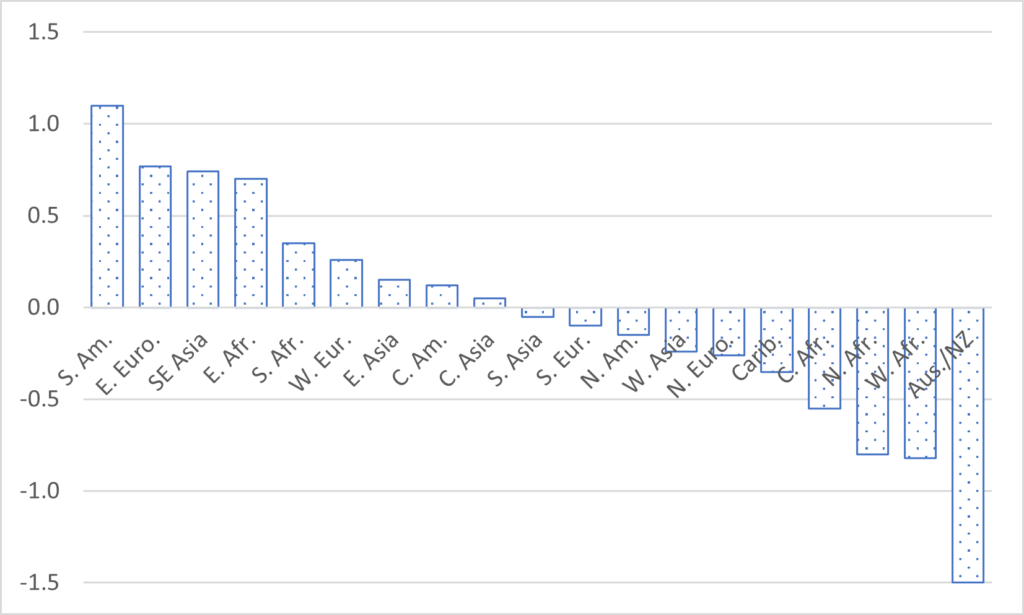

Scaling up to regions, we can look at the 19 United Nations (U.N.) Subregions to get a sense of regional skyscraperness. Regional analysis lets us look for broad patterns by grouping countries with similar cultural and economic backgrounds. When we rank regions by how much they overbuild or underbuild, we find that, in fact, the highest-ranking regions are South America, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.

Within Asia, Southeast Asia (which includes Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia), not East Asia (which includes China, Japan, and South Korea), is the highest ranked. In contrast, West Asia, which includes the Gulf nations, is not highly ranked. Within Africa, East Africa (e.g., Kenya and Uganda) and Southern Africa are at the top. For example, Bangkok, Jakarta, Nairobi, and Johannesburg contain many tall buildings given their population size and income level.

Skyline Typologies

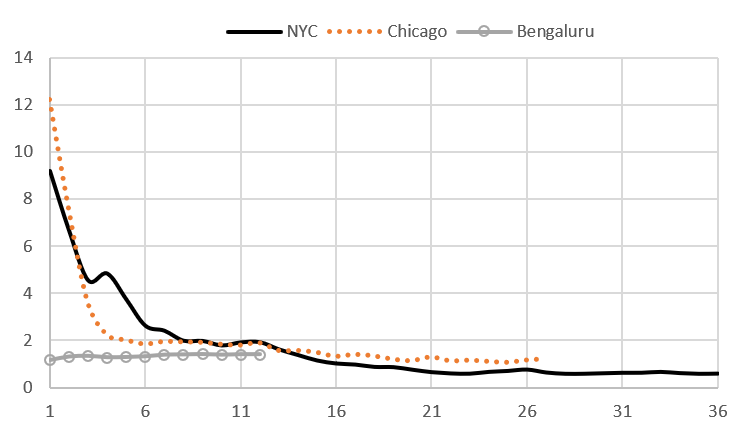

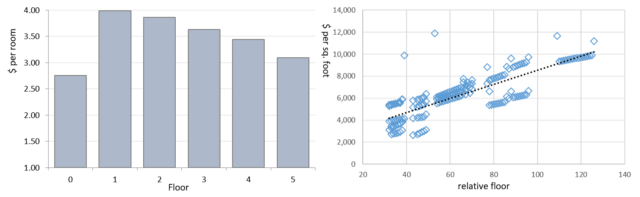

What drives such regional differences? To investigate this, we compared relative building stocks in small cities versus large ones; central areas versus peripheral ones; cities’ construction of high-rises (55 – 99 m) versus skyscrapers (100 m+); and the construction of office versus residential structures.

We then created skyline typologies by examining how countries build in these categories. Cities that mostly have office or luxury condo skyscrapers in central districts are defined as capital-oriented central district (CD) skylines—these are the exciting skylines of the world, like Manhattan and Dubai. Cities with residential and high-rise buildings in peripheral districts are defined as population-oriented peripheral district (PD) skylines. These are the boring skylines like Bogota and Rio de Janeiro.

Capital-oriented CD and Population-Oriented PDs make up the majority of the world’s skylines. But this analysis also demonstrates a key point: the most impressive skylines are not necessarily the ones with the densest tall-building stocks. For example, regions like South America and Eastern Europe make up in high-rise volume what they lose in supertall skyscrapers.

Explaining the Variation

But what might be driving cities to have one typology over another? We believe there are four possibilities.

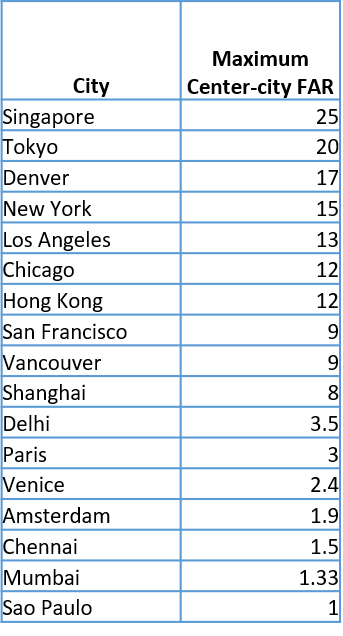

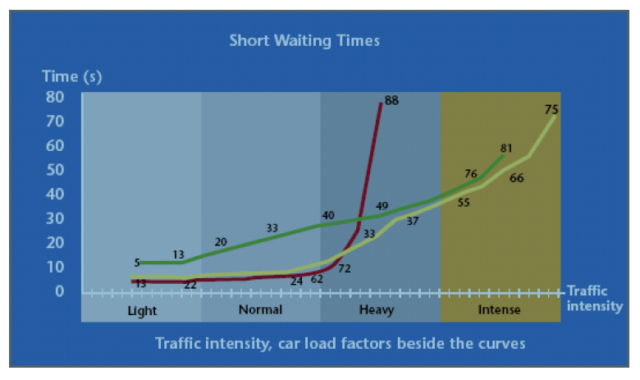

The first is land-use regulations. Many cities regulate building height in the name of reducing the negative “externalities,” such as traffic congestion and shadows. Another form of regulation is historic preservation, as residents may demand the protection of their historical buildings or height limits outside of these neighborhoods to preserve sight lines.

Another possibility is the nature of land ownership. In many older, more developed nations, land ownership can be highly dispersed among many owners of small lots. On the other hand, across China, municipal governments own vast tracts of underdeveloped land that they sell to high-rise developers to generate large housing estates. In developing nations, land assembly, particularly in regions with weak property rights, might hinder tall building construction because ownership claims are vague or diffused.

Lastly is the preference for high-rise living. Some societies may have a cultural preference for living in structures with few stories or individual houses, such as the U.S., where a free-standing house is seen as the norm. On the other hand, residents in Asian countries such as China, South Korea, and Japan see high-rise living as the norm and most desirable.

Findings

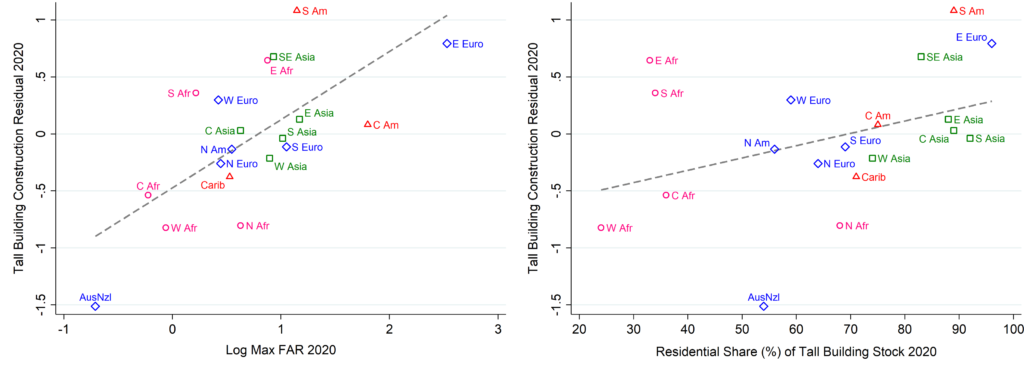

To this end, we use collected data to evaluate these four theories. We looked at the relative ages of cities and the number of world heritage sites, to gauge the difficulty of amassing lots (more historical cities would presumably have more diffused ownership) and the desire for preservation, respectively. We also looked at the average allowable floor area ratios (FARs) across regions, which measure how much building space can be provided and thus indicate the stringency of regulations. Finally, we also looked at the share of residential structures as a measure of the preferences for high-rise living.

The two most important determinants of why regions build upward or not are their FAR stringencies and their preference for residential high-rises. Likely the two things are not independent in that when citizens want to live in tall buildings, local regulations are likely to be less stringent.

The Boring Truth

When looking at global skyline characteristics, focusing on exciting skylines is misleading. About 70% and 80% of tall building heights in the world come from high-rises below 100 meters (not skyscrapers) and residential towers (not office buildings), respectively. Thus, many skylines visually appear more prominent internationally than they are after controlling for standard demand and supply variables. Hence, boring skylines are more numerous worldwide, despite suffering from a visibility problem.

So when you look up at the Empire State Building or the Burj Khalifa, remember that their heights don’t represent what’s actually happening on the ground.

—

[1] Information about the dataset and the analysis can be found in our 2023 paper, “Exciting, boring, and nonexistent skylines: Vertical building gaps in global perspective” in published in Real Estate Economics.