Jason M. Barr October 2, 2018

For millennia, after the birth of cities nearly 6,000 years ago, people world over lived in constant fear of the conflagration—the massive burning of immense swaths of the city due to accidental (or deliberate) spread of fire. Today, it is considered a tragedy if one or two buildings burn down, as the problem of conflagrations has all been but solved. But throughout history, an escaped ember or dropped gas lamp could cause untold suffering and damage. Cities well into the 19th century depended on exposed combustion to sustain their existence. As William Shields writes,

It would not be an exaggeration to say that American cities in 1800 were awash in ignition sources. Flame in one form or another was everywhere: candles, fireplaces, heating stoves, cooking stoves, oil lanterns, foundries, smithies, and so on. Lanterns were carried into stables filled with hay. Homes and businesses were heated by combustion of wood or coal. Domestic lighting was provided by candles and oil lamps, and later by gas lamps, themselves an ignition source. Smoking was common, especially of cigars that would smolder long after being tossed away. By mid-century, steam-powered trains spewing sparks entered into the heart of cities. Stationary steam engines fired by wood and coal became common power sources in factories and machine shops.

New York City

New York offers a good example of the fear and impact of fires. The city was founded as New Amsterdam in 1624 by a ragtag collection of French-speaking Walloon farmers and Dutch fur traders, under the direction of the Dutch West India Company. But as the colony took root, it became clear that fire, at any moment, could destroy all that had been created. The regulations issued by the Dutch colonial government reveal that fire prevention and suppression was an ongoing concern. New York City historian, I. N. Phelps Stokes, reviewing the city records, writes,

The danger of fire was constantly imminent in the city, where the houses were “for the most part built of Wood and thatched with Reed,” and with some of the chimneys of wood. Careless people neglected to keep their chimneys cleanly swept and failed to watch their hearths. Two houses had recently been burned from these causes; therefore, on January 23d [1648], the government ordered that no more chimneys should be built “of wood or plaister in any houses between the Fort and the Fresh Water [Pond]….”

Fire wardens were appointed to inspect chimneys, and levy, “a fine of three Guilders for every flue found to be dirty. … Notwithstanding the reaffirmation of this ordinance from time to time, it was ‘obstinately neglected by many Inhabitants.'” Over the decades other regulations were promulgated. Wood houses were banned from the city proper. Fire buckets were strategically placed throughout on the streets. And, in 1660, the burgomasters ordered,

to have erected in the Heere Gracht (Canal) at the East River [at what is now Broad and Pearl Streets] a convenient and durable lock, to keep said Gracht at all times full of water, so that in time of need because of fire . . . and at other occasions it may be used and that especially the great and unbearable stench may be suppressed, which arises daily when the water runs out.

New York Conflagrations

But these regulations were not sufficient. The rapid growth of the city and necessity of using fire for daily living and working meant that conflagrations were a grave danger. One of New York’s worst conflagrations took place during the American Revolution. In 1776, patriots allegedly torched the city during the British Occupation, destroying about one-third of its buildings. Yet, after the Revolution, despite the fact that much of Gotham was a pile of ash, the city resumed its upward trajectory. Nonetheless, in 1835, New York’s second Great Fire ravaged 17 city blocks around the Wall Street area. And only a decade later in 1845, another conflagration, destroyed another 345 buildings. Each time rebuilding began immediately afterwards.

The Great Fire of Chicago in 1871

But of course, New York was far from alone. Chicago had its Great Fire of 1871. Today it is famously credited as leading to the birth of the skyscraper (though the Fire of 1874 was perhaps more influential). The conflagration swept through downtown during the steep take-off era of the Industrial Revolution, and put the fear of the burn into the hearts of Chicagoans; never again would they suffer such a fate if they could avoid it. As the architectural historian, Frank Randall, writes,

One of the factors which contributed largely to the remarkable progress of architectural design and subsequent building construction was the great fire of 1871. This fire, in which 18,000 buildings valued at $192,000,000 were burned, wiped the slate clean, and served as a vivid warning that more permanent construction was required. To date no other city has had such a stimulus to improved building construction, together with industrial wealth sufficient to finance swift rebuilding.

After the Chicago fire, many structures were quickly rebuilt, but the financial panic of 1873 slowed reconstruction for a period of nearly ten years. Then there came a golden decade of building which culminated in the World’s Columbian Exposition. Another relatively quiet period followed the panic of 1893, but by the turn of the century the most important developments had been realized. Skeleton construction, structural steel, and caissons had been proved and accepted, and reinforced concrete was on its way to acceptance. The materials and methods of construction had been devised, and engineers and architects were in a position to meet all demands then current for height of construction.

As Sara Wermiel demonstrates in her book, The Fireproof Building, the collective search for the incombustible structure was driven by insurance companies, engineers, developers, and the business community. Because of economic growth and competition, Chicago builders had a sense of urgency to make sure they were using the latest technologies. Out of the communal process of trial and error, the skyscraper was born.[1]

Urban Growth and the Psychology of Conflagrations

Even though massive fires were a major problem, they did not stop great cities from being great. They demonstrate that, in some sense, the Metropolis is an idea, and as long as that idea is persevered, rebuilding is never out of the question. Conflagrations, generally speaking, were generational in frequency. Though the fear of them might have been ever-present, their actual manifestations were, statistically speaking, rare; rare enough that when they occurred, they engendered massive rebuilding to preserve, and improve upon, what had already been built.

A city, once “ignited” by economic growth, then creates the expectation of future growth, which, in turn, becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. The belief in growth is as important as the growth itself. To paraphrase the economist, Homer Hoyt, Chicago was a city in spirit long before it was a city in fact. For two centuries European explorers dreamed of converting the “dismal swamp” into a key transportation node, connecting the Eastern Seaboard to the Mississippi River. Once the decision in the 1830s was made to build a canal connecting Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, the city’s growth was assured.

After the fire, historian William Cronon argues, residents imagined their city as being like the phoenix, the mythical bird that would rise again from the ashes of its own funeral pyre. As long as people continued to believe in the city itself, they were able find a silver lining amidst the rubble. Cronon writes,

It was not long before Chicagoans were claiming that the destruction of the downtown had done more good than harm. Be clearing away the old wooden building stock, the catastrophe enabled businesses to erect new structures using the latest techniques for fire prevention….More important, the burn produced a construction boom that drove up the price of downtown real estate.

The Economics of Conflagrations: Recent Research

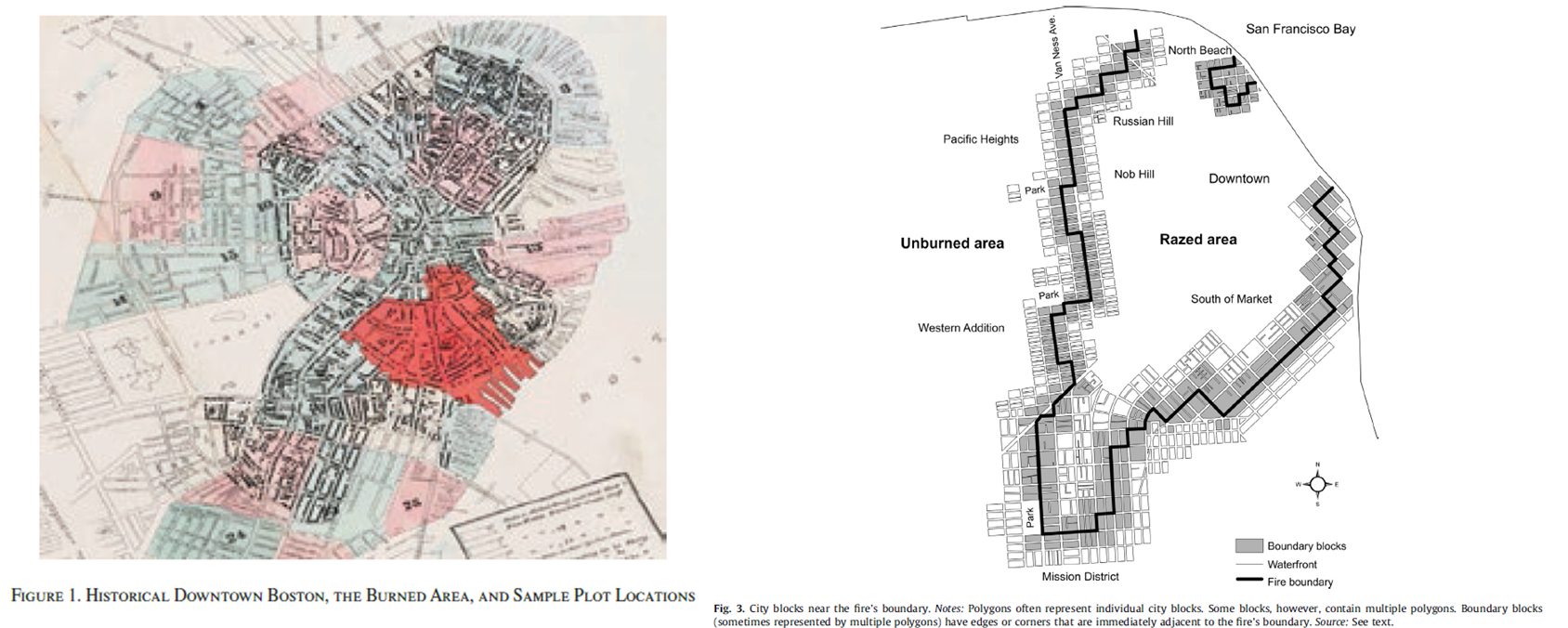

Recent research, using modern economic and statistical methods, is able provide evidence if there were, in fact, unintended benefits to urban conflagrations. The first step begins by creating a digitized map and a data set about not only the burned areas, but also the areas just outside. The seemingly random start of a fire and the seemingly random direction it takes allow for a comparison of the “treatment group” (the burned area) with the “control group,” the area adjacent that was not burned, in order to compare the effects after the conflagration.

The Great Boston Fire of 1872

On November 9, 1872, a fire broke out in a warehouse on Summer Street in Boston. Twelve hours later it was finally contained, but, before that, it destroyed about 776 buildings across 65 acres, including much of the financial district. In their paper, “Creative Destruction: Barriers to Urban Growth and the Great Boston Fire of 1872,” economists Richard Hornbeck and Daniel Keniston investigate the evolution of land values inside and just outside the burned area for several years before and after the fire. Land prices measure the value of geography itself. If values rise after a fire, it suggests a renewed confidence in the neighborhood and the city itself. If they fall, it suggests the opposite.

Based on their detailed statistical analysis, they conclude,

We estimate that the Fire generated substantial economic gains, capitalized in higher land values. Land values increased substantially in the burned area, and by a similar magnitude in nearby unburned areas, with the estimated impact declining in distance to the Fire boundary until leveling off at around 1,339 feet (25–30 buildings away). If we assume the Fire had no impact beyond 1,339 feet, the implied total increase in land value is comparable to the total value of buildings burned in the Fire.

Spillovers

They find that the destruction allowed landowners to rebuild the neighborhood essentially all at once with modern buildings that reflected the latest technology, and were better suited to the needs of the residents. This likely had the effect of increasing the population and business density, as the new buildings were able to accommodate more people, which, in turn, made the geography more valuable.

Just as importantly, landowners whose buildings did not burn obtained an indirect benefit from the rebuilding efforts inside the burned zone. The reconstruction efforts made the neighborhood as a whole more valuable because the structures were now of both a greater quality and quantity. Rising land values likely drove landowners outside of the burned area to tear down their older buildings and go along with the modernization wave.

The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906

On April 18, 1906, at 5:12 a.m. a magnitude 7.9 earthquake struck the coast of Northern California. San Francisco was badly hit, and it triggered a conflagration, destroying more than 28,000 buildings. Ironically, the vast majority of the city’s destruction came not from the earthquake itself but from the fires it triggered. A research paper entitled, “Razing San Francisco: The 1906 Disaster as a Natural Experiment,” by James Siodla, looks at the effects of the conflagration in San Francisco. In particular, he focuses on residential population density before and after the fire.

Using a similar statistical approach as that of Hornbeck and Keniston, Siodla compares population density growth within the burned area to just outside. He finds that it went up in both the burned and non-burned areas, but the burned areas saw a much steeper rise. In other words, the rebuilding allowed for landowners to construct modern apartment buildings to cater to the demand to live and work in San Francisco. This rise in population density in the burned areas persists today, and so those neighborhoods continue to have a better ability to accommodate people who want to live in the city.

What Does this Research Suggest about Cities Today?

As the research above demonstrates, a silver lining to the conflagrations was the ability to rebuild large parts of the central city nearly all at once. In other words, the fires released some “frictions” that were holding owners back from updating the building stock, where frictions mean some additional cost or hurdle that prevents landowners from changing the use and quality to that which best accommodates the demand.

It is also important to point out that the rebuilding efforts discussed above happened before the implementation of comprehensive zoning and land use regulations, which were not adopted in American cities until after 1915, following New York City’s lead in 1916. Thus the reconstruction efforts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were based on the decisions of individual property owners. A key point is that even in a city without zoning or land use regulations (or NIMYBism), there are strong incentives preventing a city from modernizing itself.

So what might be some of those inherent barriers, especially in a rapidly growing city? One might be uncertainty. If landowners are unsure how the neighborhood might evolve, they may find it better just to wait. But if one landlord thinks it is best to wait, many others likely feel the same way. Another hurdle might be the costs and time related to redeveloping a property. Developers must empty a building, tear it down, and then spend several months erecting the new structure. This represents a significant loss of income during the process. It may be that many building owners were comfortable with the incomes their current properties were generating, and did not feel compelled to modernize. (And imagine how much larger theses hurdles are for single family owner-occupied residents.)

Zoning and NIMBYism add an additional layer of frictions to the real estate market. As the world around a city changes, if the city itself is inhibited from changing with it, society is worse off. First, in a growing city, if supply cannot match demand, housing becomes much more expensive. This also exacerbates income inequality, since the owners of land are given a kind of monopoly power over renters. Second, it also reduces economic growth. Buildings need to adjust to accommodate the changing nature of work and the changing lifestyles of city dwellers. Converting loft buildings to condos will only get a city so far; while allowing carbon spewing single family houses to use up a majority of a city’s land acts a bottleneck to a better quality of life for its residents more broadly. And, finally, redevelopment hurdles prevent people who would like to move into the city from doing so, because they cannot be accommodated (and this also limits the spillover benefits from urban density).

To be clear, it’s important to find the right balance between modernization and preserving a city’s architecture and feel. But in this day and age, the suite of (often well-intentioned) government-imposed limitations only serves to add more barriers to a market that has them to begin with. This is like pouring liquid nitrogen onto an ice cube.

—

[1] Ironically, though Chicago was the one of the first cities to build skyscrapers, it retained a “fear of heights” from the Great Fire. In 1893, the city capped the heights of its buildings at 130 feet. While over the decades, the height cap moved up and down, they served to help New York take over the skyscraper leadership.