Jason M. Barr June 12, 2023

A few weeks ago, I received an email from an acquaintance with a link to an article about my research. I was naturally intrigued, but when I started reading it, I realized that the author was using my research against me, rotating the findings to suggest they meant the opposite of what they actually meant.

The article is “Death to the Skyscraper,” and the author paints a very dark—dystopian even—picture of the skyscraper. She is not alone, to be sure. Her article is part of a long-running genre of skyscraper-as-destroyer-of-cities.

Her focus is on the environmental impacts of tall buildings, particularly their greenhouse gas emissions. It’s true that tall buildings tend to produce more through operational and embodied carbon than their diminutive counterparts. And this observation is, correctly, worrisome.

For those who see these “towers of power” simply as carbon-spewing Godzillas, the natural conclusion is that they should be banned from existence. But as I teach my students in Economics 101, you can’t draw conclusions without evaluating the costs relative to the benefits. Unfortunately, the whole article reads as an exercise in bad economics.

The Enduring Skyscraper

The author’s key thesis is that the skyscraper requires more of society than it gives in return. This claim puts her within a century’s-long tradition of those who have shared that view. In fact, her words (which are factually dubious at best) that “Even at the city level, the huge carbon cost of skyscrapers fails to outweigh any potential benefits that they might achieve from restraining urban sprawl” echoes one of New York’s key reformers, Edward Bassett. He sought to eliminate the skyscrapers in Manhattan by focusing only on their construction costs while ignoring their benefits. In a 1913 report that led to New York’s 1916 zoning resolution, he wrote:

Few skyscrapers pay large net returns. Most of them pay only moderate returns….However, the very tall buildings demand many things out of proportion to their increased bulk. All piping has to be made disproportionately heavier; special pumps and relays of tanks have to be provided, foundations often call for special construction, wind-bracing assumes an important place, long-run elevators are more costly than short-run elevators, the extra space taken up by the express run of the elevators is an additional cost. Thus in the aggregate the total cost per cubic foot of a very tall building may be 60 to 75 cents per cubic foot where a low building of the same class would cost only 40 to 50 cents per cubic foot.

But just because something has higher costs (either to the builder or society at large) does not logically lead to the result that it should be eliminated. To evaluate the claims more fully about tall buildings, we need to take a step back—or up—and put them in context to view the skyscraper trees within their economic forest. One should not make pronouncements about urban real estate without more widely considering how cities function.

Why Do Cities Exist?

Since the skyscraper is one species within the urban environment, we need to begin with the question: Why do cities exist? Or flipping the coin, why does the majority—and growing—of the world’s population live in cities? The fundamental answer is “markets.”

Cities are, first and foremost, labor markets. They are where people find jobs, and, in this sense, cities are the engines that power our economic lives. To take a simple case in point, the three most productive counties in the U.S.: Manhattan (New York County), Los Angeles County, and Cook County (Chicago), together generate 9% of the United States Gross Domestic Product (GDP), yet they use 0.18% of its land mass.

People come for the jobs but stay for the opportunity to experience all that a city has to offer, like restaurants, museums, or large urban parks. Even working from home will not drive us out of the city. It might cause some relocations and adjustments, but in the end, the city will maintain its roles.

Hivetropolis

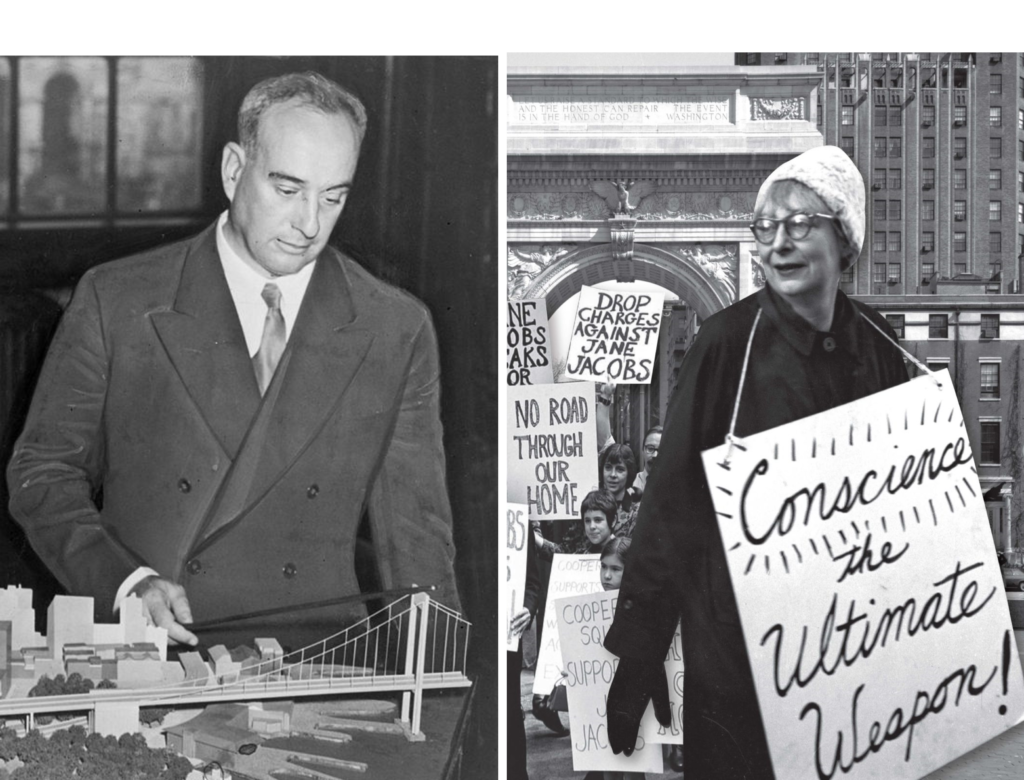

And, as Jane Jacobs has argued, cities are inherently problem-solving machines that draw their power from density itself. Ideas and hive intelligence are in the urban ether, and if we allow cities to function as they should—if we allow people to live and work where they see fit—then cities can continue to provide both the income from our labor and the goods and services that we want as consumers and citizens.

Now, if you concede that the purpose of the metropolis is to be the center of what is necessary, right, and good, then we must ask, how is the city to organize itself to function for maximum efficiency and gain? The answer is through the land market.

Allocating Geography

As nicely summarized by urban planner and author Alain Bertaud, the land market

sends strong signals though prices when land is underused or the use is unsuitable for its location;…provides a strong incentive to users to use as little land as possible in areas where there is a strong demand, in particular in areas well served by transport networks; and…stimulates innovation in construction.

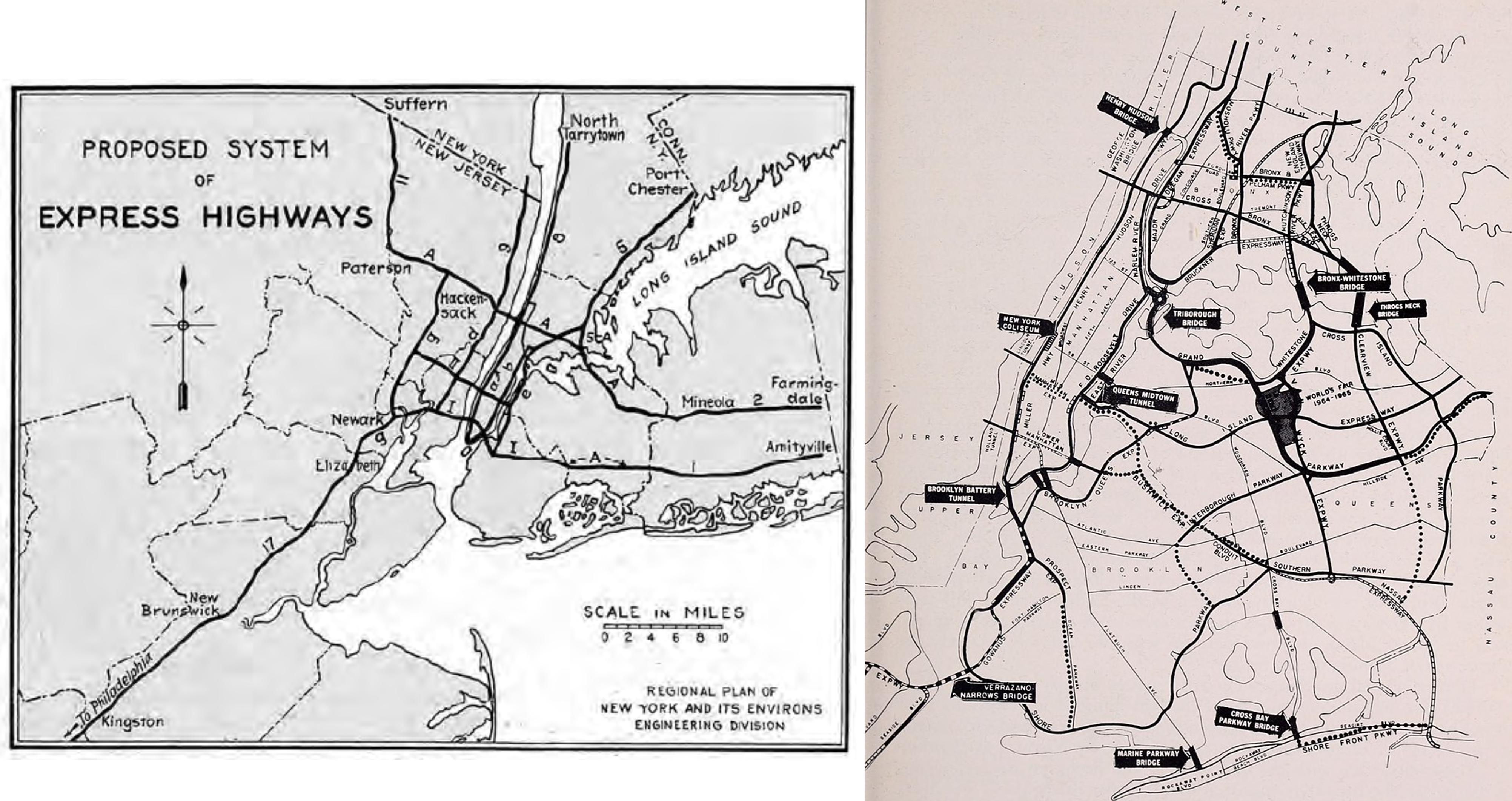

This means that to understand what “should” go where, land prices are the most valuable signal. But high land values are really a signal of the value of geography—that more people and businesses want to be in the same place at the same time. Thus, the skyscraper is a geography-shrinking machine. It pinches the land to squeeze out new land—land in the sky—which allows hundreds, if not thousands, of people to be in the same place at the same time.

Good Communities

But what are we to make of the author’s conclusion that:

High land prices, of course, are not good for ordinary people and communities: they segregate societies along socioeconomic lines, with high costs of homes and rent pushing people into low standards of living, and risking their health, development and life chances. A city birthing new skyscrapers is likely to be unaffordable for many of its residents.

I have a few responses. First, a trip to Hong Kong, Singapore, or any mainland Chinese city, for example, would reveal that high-rises are not just the province of the rich—rather, high-rise after high-rise is home to Asia’s burgeoning middle class. So, there’s nothing inherent in the economics of tall buildings that precludes their use by many across the income spectrum.

Second, the segregation of uses is only partly the result of land markets. Tall buildings in the center are economically rational because they satisfy the need for people to be closer to each other. They make businesses more productive and allow more residents to enjoy the fruits of the city by saving on commuting and travel times. And the empirical evidence strongly supports this conclusion.

But even in the most central locations, there’s ample opportunity for a mix of building types and income levels. A quick stroll down Wall Street—the center of global finance—will reveal short buildings next to tall ones and old buildings next to new ones.

Zoning

The more important issues, however, are planning and zoning. While Jacobs argued in the 1960s that planners ought to get out of the way and let cities be, the opposite has occurred. Bassett and those who followed him could not stomach population density and mixed uses. They created zoning arrangements that made mixed uses illegal. Even today, it’s impossible to have a tall building in New York that contains one-third for shopping and restaurants, one-third for offices, and one-third for apartments, despite that office buildings remain largely underused.

Regarding hyper-segregation, the evidence strongly suggests it is due, in large part, to the historical planners’ fear of mixed uses and their desire to surgically separate all land use types regardless if people wanted them or not. They aimed to keep factories away from residences and single-family homes away from apartment buildings. Zoning was meant as a backdoor to means to create the ideal cities according to planners’ view that workers should all live in Garden Cities, and the center should be designed according to the highest City Beautiful ideal.

Once zoning took root in the first half of the 20th century, wealthier residents used these restrictions to limit housing, which made access to these places nearly impossible for a vast swath of society. The concomitant redlining of neighborhoods was a product of racism and the Federal government’s desire to protect white people’s home values.

Nimby Nation

Because of the tight restrictions in suburban areas, nearly the only place in the city today where builders can provide needed housing is in the center, where the land values are the greatest and zoning tends to be less restrictive. The irony is that renters have made common cause with single-family Nimbyists because they see the “greedy developer” and the “greedy landlord” as “ruining their neighborhoods” and driving up housing prices, even though renters stand to gain the most from new construction, which will lower rents.

And the Nimbyists preaching the “Gospels of Saint Jane” to limit building heights in the name of the “human scale” are, in fact, making it harder to build new housing and causing land values and rents to rise. So, the very people who rail against tall buildings are incentivizing them by their very actions.

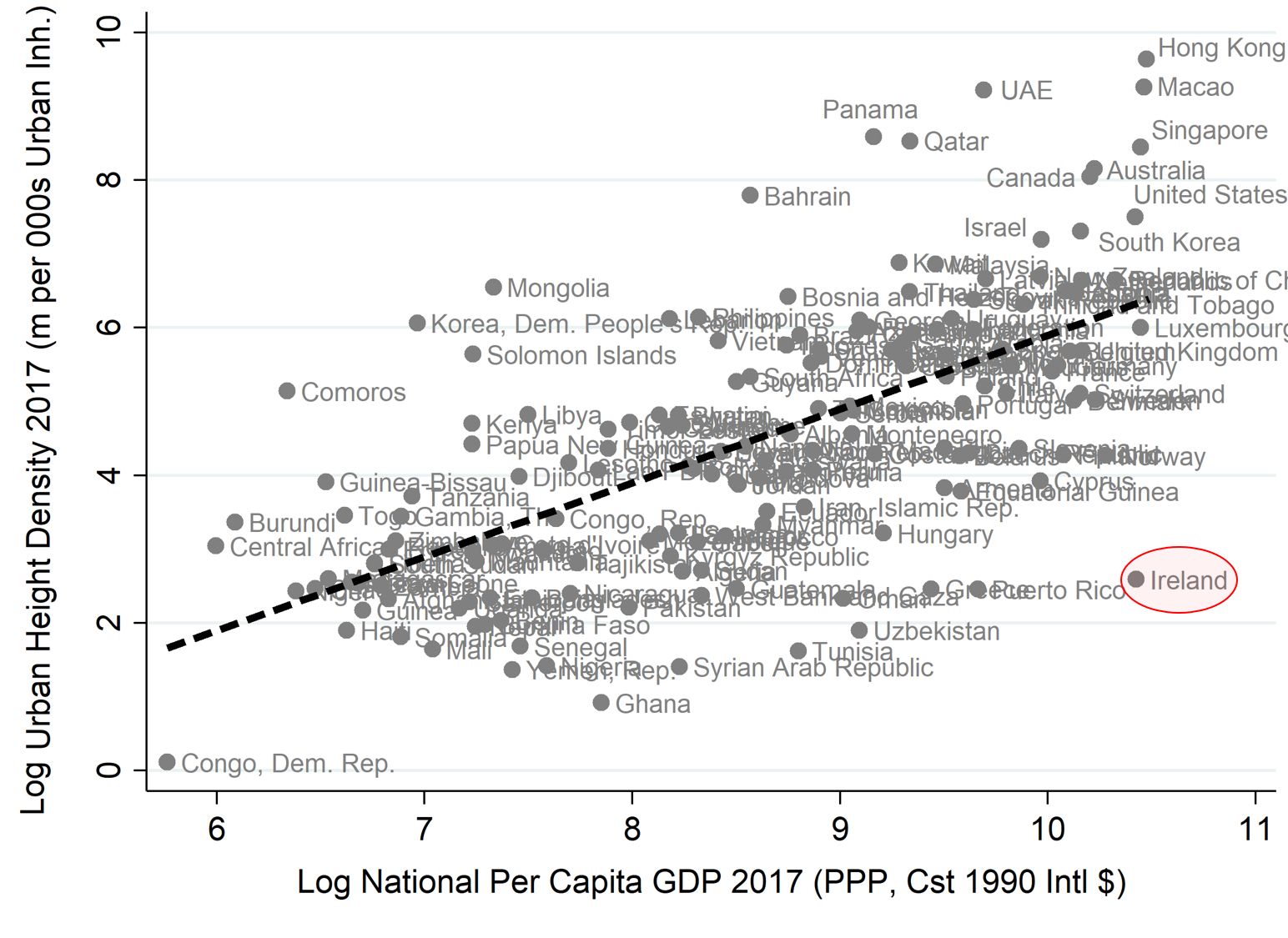

But taking a broader perspective, tall buildings are not causing the affordability problem. Using New York as an example, the city has 3.6 million housing units, and 77% are in buildings that are ten stories or less, and 2.7% of units are in buildings 40 stories or taller. Taking a global view, in the developed world, 86% of its structures are 25 meters (8 floors) or less, 94% are less than 15 stories, and 99% are less than 100 meters (25 stories). The supertall part of the spectrum represents only a tiny fraction of the world’s buildings.

Are There Too Many Skyscrapers?

So, with this in mind, we turn to the question of what’s to be done. There’s a valid argument that cities are getting too many skyscrapers because of restrictive building regulations in the suburbs and GHG emissions.

Skyscrapers produce a lot of CO2. No one disputes that. But this fact does not mean they should be banned from existence. Banning something that makes cities function properly is a bad idea. Density is what powers cities, and density should be encouraged rather than discouraged.

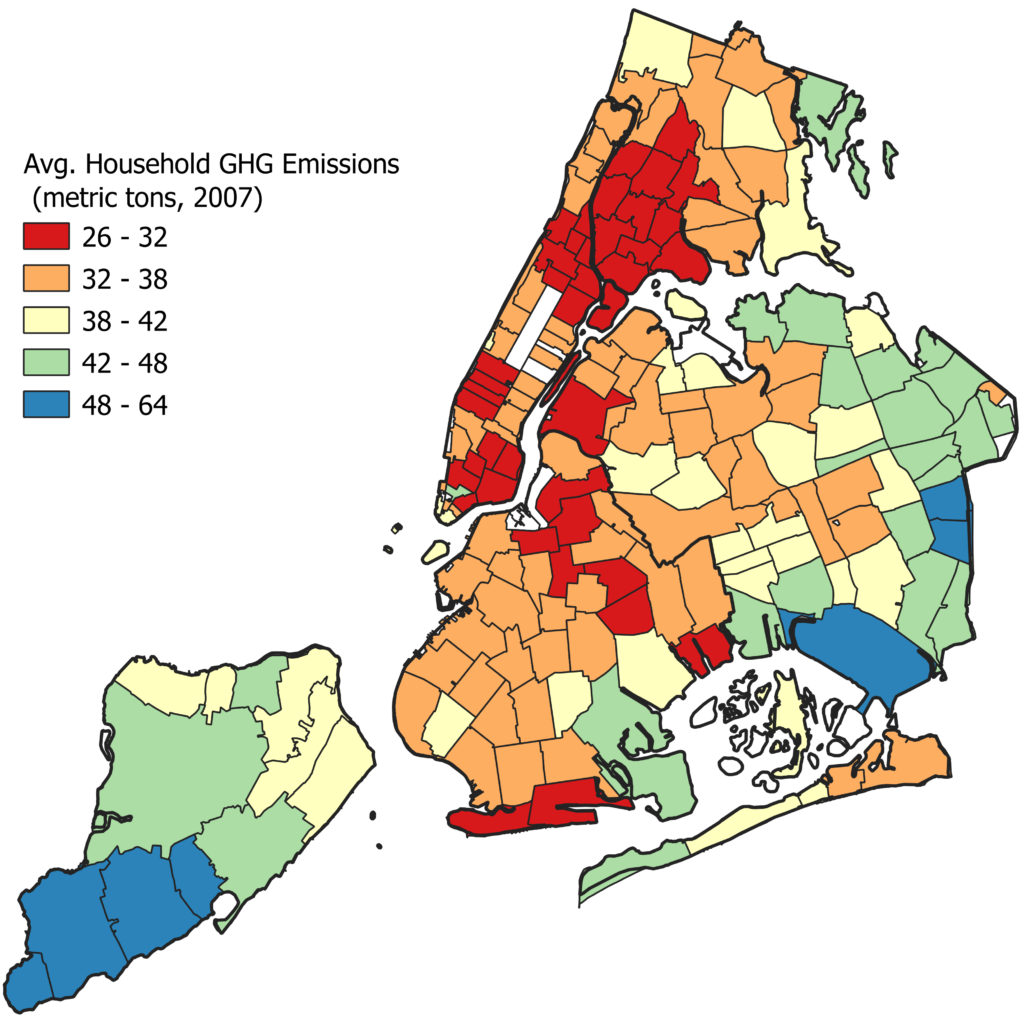

More broadly, there’s an extensive literature in economics demonstrating one simple fact: If you put draconian restrictions on what a city can build, the outcome is more sprawl and traffic congestion, and higher housing prices. Similarly for GHG emissions, Manhattan has far lower carbon footprints per household than its suburbs.

Using a data set with estimated average household carbon footprints for every zip code in the United States, we can conduct a thought experiment. Imagine we “Manhattanized” the two suburban counties adjacent to New York City—Nassau and Westchester—by having all their residents live at the same density. Those two counties would see a reduction in their residential carbon footprints by 41%.

Do We Really Need More Paris’s?

And yes, 5-story buildings are the best in terms of minimizing carbon emissions, but again it does not logically follow that we should require by fiat that every city be built like Paris. It is worth noting a few facts about the place. First, officials created a skyscraper district in La Défense because they knew they needed tall buildings for the economic health of the city. Second, if you look at Paris’s global ranking, in terms of its importance in the world economy, as measured by the size and number of international firms, it’s falling. Paris in 2000 was ranked 4th, and by 2020, it was bumped down to 8th, losing out to skyscraper cities. Is it because of Paris’ lack of tall buildings? The data are strongly suggestive, though more research is needed.

In the last decade, Paris has shrunk by 122,000 residents. As reported in Forbes.com, “Many of those leaving are choosing either the suburbs or countryside around Paris, or they are relocating to France’s smaller cities such as Bordeaux, Lyon, and Toulouse.” By limiting its building stock, Paris is driving up housing prices, pushing out residents, and causing suburban sprawl—hardly something worthy of emulation.

Think Externalities

Critics love to blame tall buildings for destroying the environment, but they (like us all) think little of turning on the air conditioning when they are hot, charging their laptops when they want to check Twitter, or hopping on a jet to go on vacation. But we would hardly say these should be eliminated from our lives.

To offer another illustration, where I teach, most students commute to class. Every semester, I informally poll them by asking them to raise their hands if they decided not to drive to class that day and took mass transit instead because they knew their car would emit some carbon during their commutes. I don’t think I’ve ever had a student raise their hand in the affirmative. They decide to drive or not based on whether they have access to a car and on the availability of parking.

The point is that CO2 is what economists call an externality, an unintended by-product of our actions that generates a negative effect on society. Greenhouse gas emissions are the mother of all externalities and should be treated as such. Since no one is willing to give up their comfortable lifestyles, that means we must rely on carrots and sticks to generate technological improvements that replace our current products and energy production with carbon neutral alternatives.

Tax Carbon

As I teach my students in Economics 101, the key to solving the externalities problem is for producers to “internalize” them so they pay for the costs that they would otherwise impose on others. The most effective ways to do this are to tax carbon emissions or create a cap-and-trade scheme. Cities around the world, like New York with its Local Law 97 and London with its carbon taxes, are generating penalties for GHG-heavy building owners. This is good.

I would argue, however, that New York’s law, for example, does not go far enough. All households—not just those in large buildings—should face a carbon tax. If cities charged all household “over producers” and gave credits to “under producers” based on their emissions, it would not only be fair—the rich would pay more in taxes—but would also benefit those living in efficient buildings. A household carbon tax and a gasoline carbon tax, would also encourage denser, less-car-based lifestyles, which would lower GHG footprints that much more.

Federal Policies

Help must also come from the Federal Government, which should penalize CO2 creation and reward alternatives that use less or no CO2. For example, steel and cement producers need to pay for the carbon they generate, while R&D credits should be given to businesses that develop low-carbon products or production methods. Electricity providers need subsidies and incentives to switch to wind, solar, and other clean energy forms, as well as to upgrade the electricity grid.

And globally, the developed nations must help the developing countries to produce their skylines with low-carbon methods. They want American lifestyles and feel that they should not make the sacrifices that the West never made. At the end of the day, solving the global climate crisis must be an international effort.

Towers of Power?

Towers of Power—the supertall buildings for billionaires—are a result of booming cities, but they are not the cause of gentrification. Gentrification is due to the gummed-up nature of cities. It is largely driven by overly restrictive zoning and price controls enacted to save the city from itself but has served chiefly to inflict more harm than good.

Since the restrictive zoning is driving up land value in the city centers, we should eliminate the outdated zoning rules and replace them with a rational plan that more carefully weighs the costs and benefits to neighborhoods. By allowing more moderately taller, mixed-use buildings throughout the city, we would decrease the bottlenecks that make land prices skyrocket in the center, thus reducing the incentive for developers to build supertalls.

Affordability

It’s important to reiterate that if you ban tall buildings, it does not logically follow that you would get affordable housing for lower- and middle-income households. Banning skyscrapers will make the affordability problem that much worse because tall buildings, in fact, are helping the affordability problem by providing more housing on less land. However, it does so in a rather indirect way–by “greasing” the moving chains from the top to the bottom of the housing spectrum.

Money seeks its highest return. So, the question is, why doesn’t more real estate money flow to lower-income housing? Despite what many people think, the real estate market does not operate according to some made-up rule that either we get skyscrapers or we get affordable housing. Money is not flowing into middle-income housing because it is illegal to build it in most parts of big cities, thanks in large part to stringent planning and zoning regulations, and other frictions that need to be addressed by policymakers.

If people were really concerned about gentrification, they would demand their leaders enable builders to flood the market with middle-income housing in the suburbs. This would cool land values in the center and provide units for those who need them the most.

Skyscrapers and Cities

Skyscrapers don’t belong everywhere and are not for everyone. But policy discussions are severely harmed when people use loaded rhetoric, poorly-defined concepts, and buzz phrases to make grand pronouncements based on little more than casual observations. Skyscrapers have spread like a wave over the planet in the 21st century because they help cities grow and succeed.

But yes, we need to carefully consider their costs and benefits to evaluate where policy changes can offer improvements. And there’s room for disagreement, but we can all agree that cities should be open and accommodating to all who want to call them home.

Thanks to Troy Tassier for his editorial comments on an early draft of this post.