By Jason M. Barr November 5, 2017

In 1999, an economist named Andrew Lawrence thought he saw a relationship between the business cycle and skyscrapers; he dubbed this the “Skyscraper Index,” and it purports to demonstrate the “Skyscraper Curse,” which is,

an unhealthy correlation between construction of the next world’s tallest building and an impending financial crisis: New York 1930, Chicago 1974; Kuala Lumpur 1997 and Dubai 2010. Yet often the world’s tallest buildings are simply the edifice of a broader skyscraper building boom, reflecting a widespread misallocation of capital and an impending economic correction.

It has proven a very seductive idea, and the media and public have glommed onto it as some kind of infallible truth. But the idea that the construction of the world’s tallest building is a harbinger of economic doom is specious.

It is an example of what I call Rorschach Economics: people see a relationship because they want to. It is easy for the eye to produce patterns that don’t exist, despite the fact that they come from random chance. (In this nice coin tossing simulation example, you can see that “patterns” are really naturally occurring randomness.)

Economic downturns, panics, and/or crises happen very frequently, much more frequently than record-breaking skyscrapers. By my count, there have been at least 28 panics, crises, or severe downturns in the last 125 years, over twice as many as record-breaking buildings. So it’s quite easy to find a crisis and pair it with a tall building, proving the adage that even a broken clock is right twice a day.

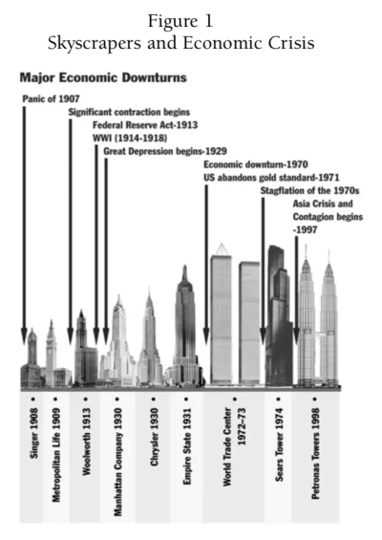

The “Skyscraper Index” is not even an index, which is a set of measurements that represents the average value of something, such as the Consumer Price Index, which measures the cost of living, or the Dow Jones Industrial Index, which measures the value of 30 large-company stocks. The “Skyscraper Index,” on the other hand, is simply a montage that shows pictures of the world’s tallest buildings over a time line with some “nearby” financial crises.[1]

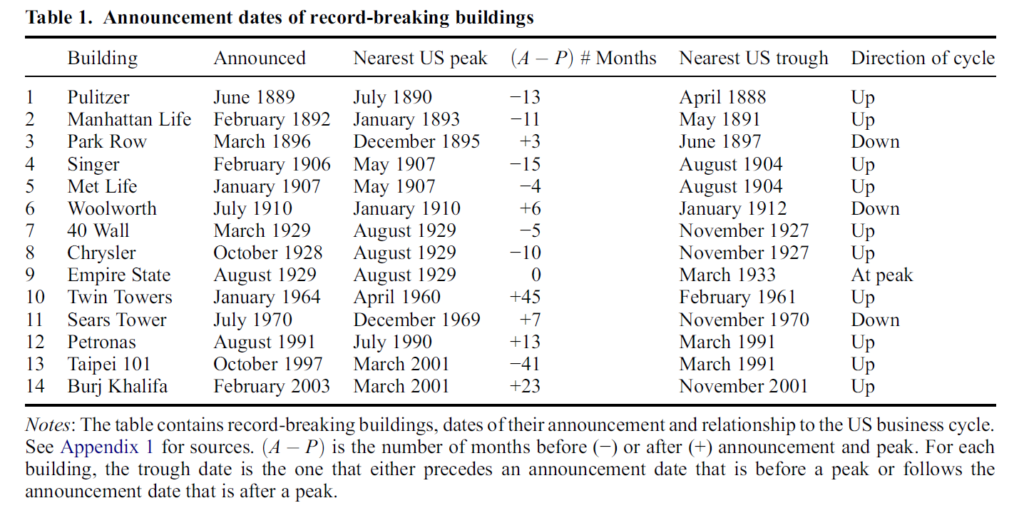

The point of generating real indexes is that you can then use them to perform statistical tests to avoid conclusions based on “truthiness.” This just what I, along with my co-authors, did. We performed two kinds of analyses. First, as a very simple test of the “Skyscraper Index” hypothesis, we found both the announcement and completion dates of the world’s record-breaking buildings, and looked to see where they fell within the business cycle. We used the U.S. business cycle—which is based mostly on changes in Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—because of its importance for the world economy, and because, until relatively recently, all the record breakers were in the U.S.

Table 1 lists all of the record-breaking buildings completed since 1890, the dates that the developers first publicly announced their decisions, and the timing within the business cycle. While it is true that 10 of them were announced during an upswing in the cycle, the range of months between the announcement and cycle peak is tremendous, varying from zero to 45 months.

Looking at the opening dates of the buildings shows a similar story. Table 2 provides the date of opening of each building (i.e., either the official opening or the date that the building received its first tenants), the closest peak, and subsequent trough.

First, we can see that only half were completed during the downward phase of the cycle, and furthermore, there is no pattern between when the building is opened for business and when the trough occurs. The range is from one to 54 months. In short, there is no way to predict the business cycle, based on either when a record-breaker is announced or when it is completed.

In a second exercise, we collected data on the tallest building completed each year in the U.S., Canada, mainland China, and Hong Kong, and their respective annual GDP values. Using the statistical technique of vector error correction modeling, we attempted to predict changes in GDP from the heights of completed skyscrapers. The bottom line: you can’t do it. For decades, economists have searched for the holy grail of forecasting that predicts the end of economic bubbles. Alas, skyscraper height is not it.

Yet despite the fact that there is no real evidence, it has not stopped writers from reporting on the relationship, and even making up new relationships along the way. The Skyscraper Index was originally a story about the newest world’s tallest building, but now has morphed to apply to any very tall building. The strategy is to say, “here’s a new supertall; a crisis must be on the way.” Or, writers go out and find a crisis that conveniently pairs with a new building.

Here are a few examples:

The Lotte Tower: Two journalists on Bloomberg.com, in March 2017, claim that the Lotte Tower, a 123-story skyscraper completed is Seoul in 2017, has cursed South Korea. The authors proceed to itemize a series of political and economic problems that thus “proves” a connection, including the corruption scandal of Park Geun-hye, Korea’s former President. So now, the “curse” extends to political crises. Good to know.

The Shanghai Tower: In this January 2016 Washington Post Wonk Blog, the author suggests that the recent official opening of the Shanghai Tower (128 floors) “caused” the Shanghai stock market to go down on the same day. Then she proceeds to discuss how the skyscraper is likely to unleash an economic plague upon China. Best I can tell, China is still humming along; its 2016 GDP growth rate was 6.7%, more than double that of the U.S.

The Jeddah Tower: In 2020, the new world’s tallest building is slated to open in Saudi Arabia with the soaring height of one kilometer (3,281 feet). The author of this 2015 PBS.org blog is already predicting gloom and doom for the kingdom five years before completion. Apparently, he is an expert on spotting financial bubbles before they burst. So much so he is already predicting the next bubble (and crash) before it even starts. Now that’s foresight!

So note to journalists, bloggers, and would-be clairvoyants: the “Skyscraper Index” is NOT an index, the “Skyscraper Curse” is bogus, and skyscraper heights cannot predict the future. That is all. ♦

[1] In the interest of scientific replicability, I, too, have created a “New Skyscraper Index,” which shows an eerie relationship between skyscraper heights and maritime disasters.