Jason M. Barr February 21, 2024

[Note: Starting on Monday, March 4, 2024, Gerard Koeppel and I will be co-teaching a six-week online course on the history of the Manhattan grid plan for the Gotham Center for New York City History. More information and registration can be found here.]

“I’m on First and First. How can the same street intersect with itself? I must be at the nexus of the universe.” – Cosmo Kramer, Seinfeld, 4/30/1998

Gotham Reborn

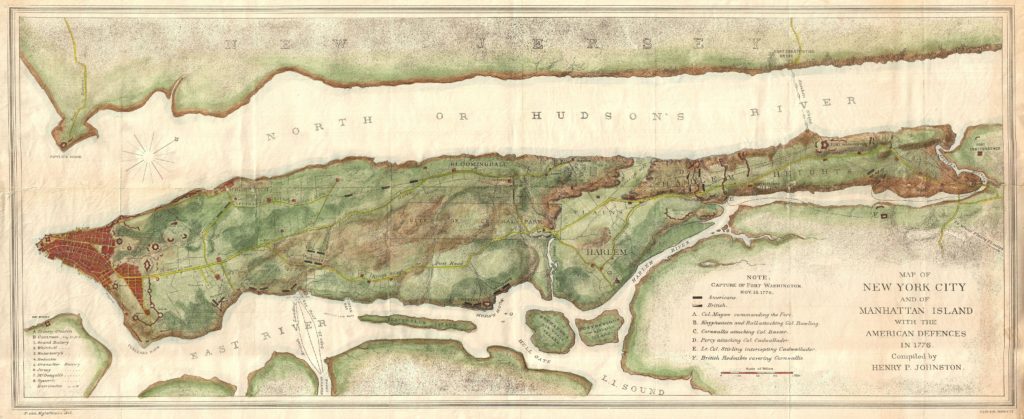

In 1783, Gotham lay in ruins. Seven years of British occupation inflicted many wounds, including conflagrations, disinvestment, and decay. But the kernel of a great city remained, and after the Revolutionary War, New York began to rebuild—but in the same manner as before—rapidly as the demand warranted and with little planning. In 1790, though New York was still a small city of about 33,000 residents, its prospects seemed bright.

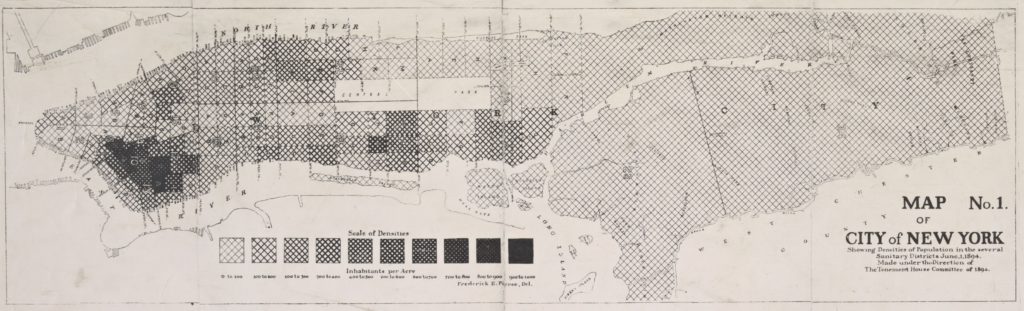

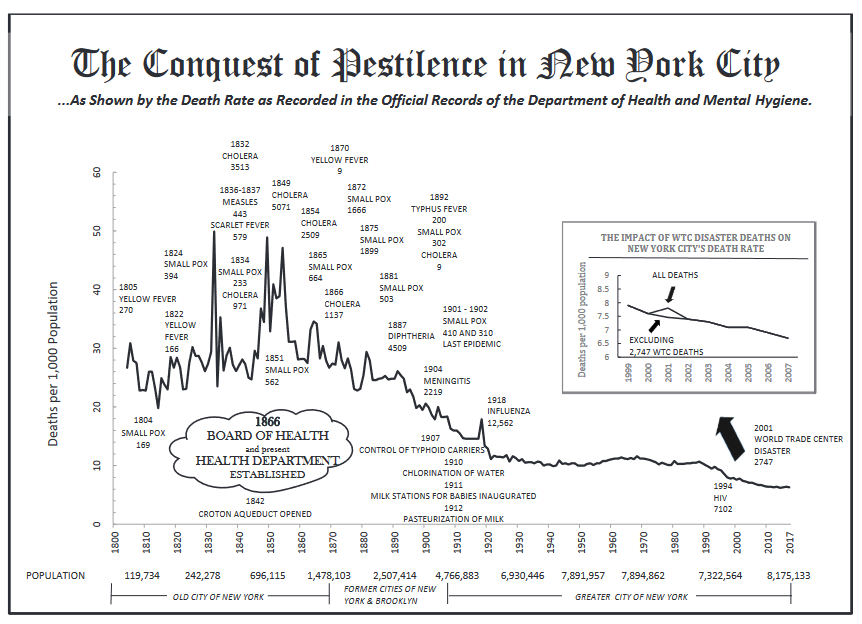

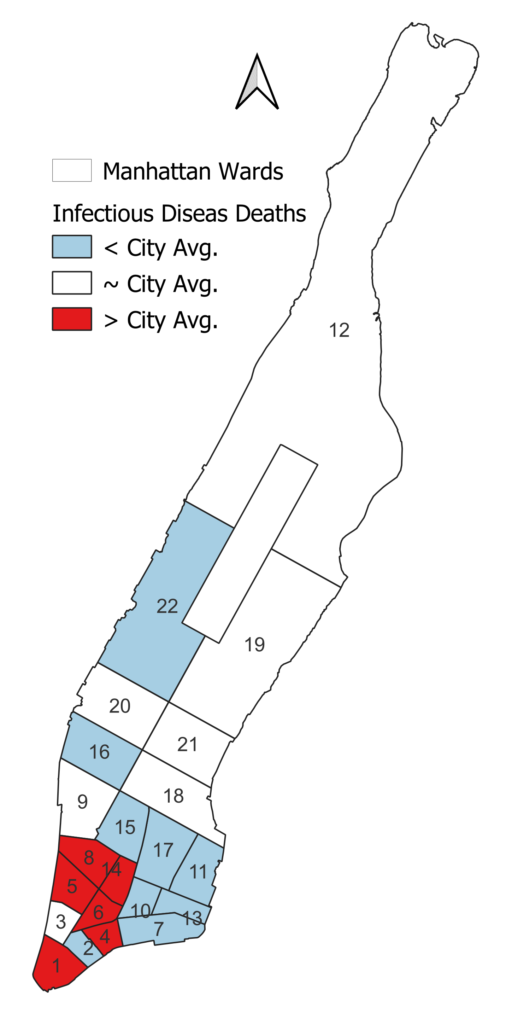

The city leaders felt the time was right to consider the future. The lower tip was a tangle of old streets formed during the Dutch days. Disease outbreaks occurred with depressing regularity. In 1795, a Yellow Fever outbreak caused 732 deaths; in 1789, it killed over 1,300 residents. It returned in 1803 to take another 600 souls, and two years later, it took another 270 lives. Above the city proper was rural Manhattan, comprising some 170 farms and estates, which would soon be folded into the city proper. If not careful, New York would replicate and exacerbate its ongoing problems of conflagrations, congestion, and epidemics.

Early Precedents

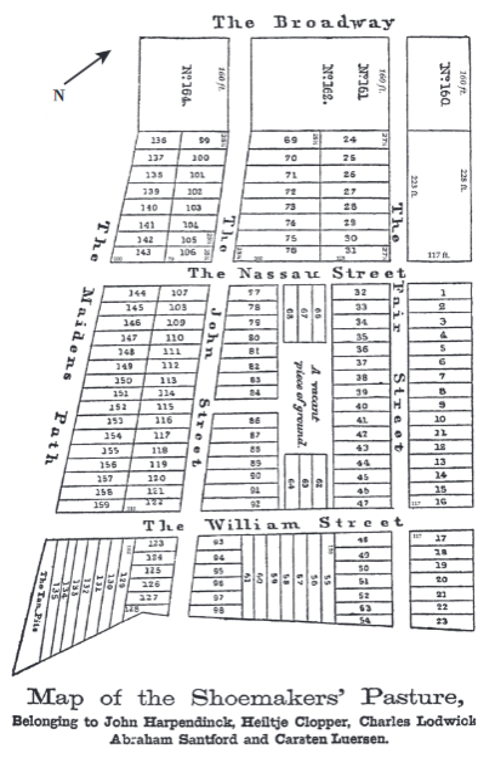

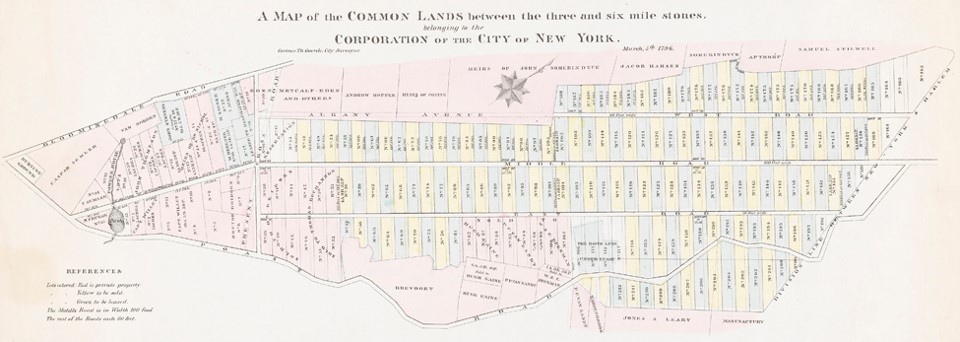

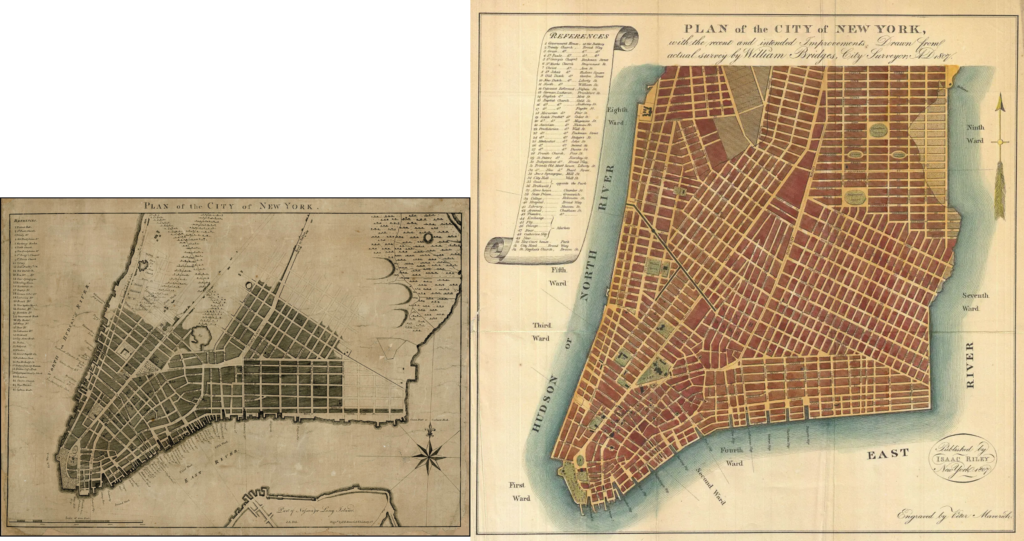

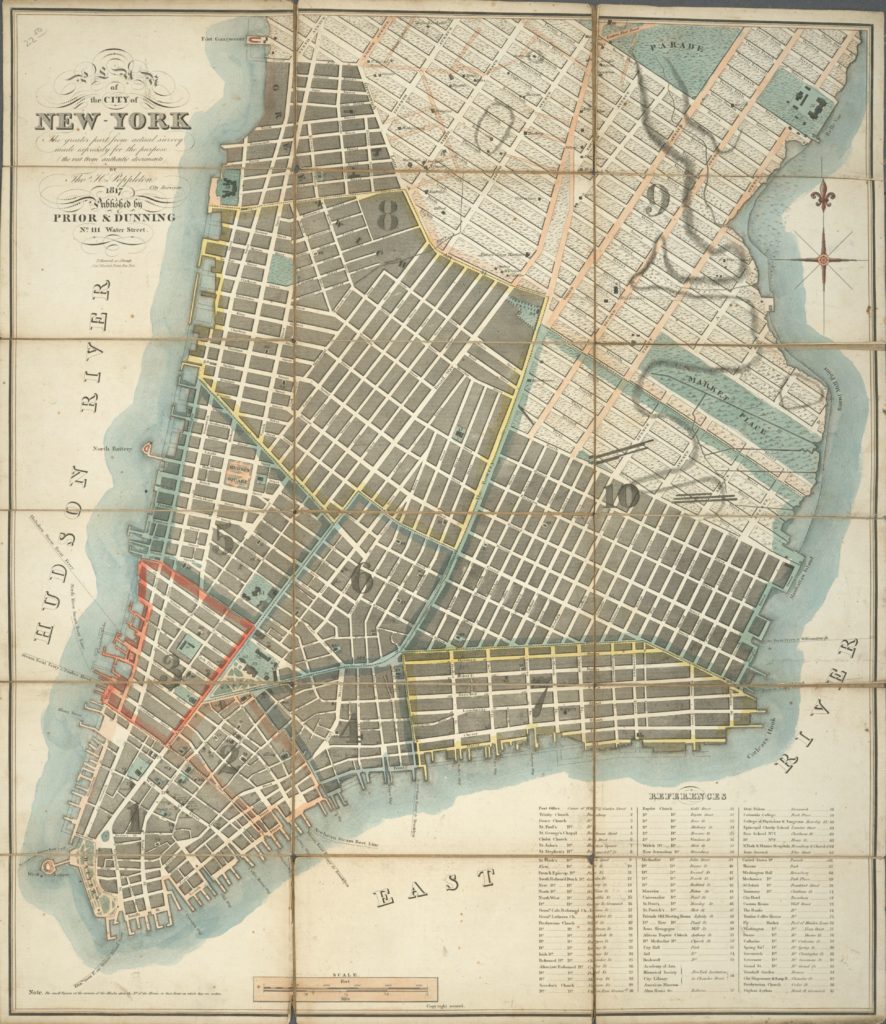

By 1803, however, the municipality had commissioned two important mapping projects. The first was the plating of the Common Lands, 1,300 acres of city-owned property in the center of the island. The next was a street plan produced by Joseph Mangin. However, the Council rejected it. But, as grid historian Gerard Koeppel documents, Mangin’s map fostered the idea that New York could and should have a street plan.

And the Common Council was determined to try again. In 1807, it petitioned the state to empower a planning commission to give the City the extra power it felt it lacked to see a new plan through to completion. The Council realized that without the force of state law, a new Council could be elected that might undo the plan, especially if residents voiced opposition. The law specified the names of three commissioners: Gouverneur Morris, Simeon De Witt, and John Rutherfurd.

The Commissioners

Simeon De Witt was a clear choice because he was a renowned surveyor, having mapped many miles of New York State before being chosen for Commission. He was also selected in 1810 as a member of the first Erie Canal Commission to help survey the canal’s route, completed in 1825.

Gouverneur Morris was a Founding Father who wrote the Preamble of the Constitution. He was a member of the Continental Congress and served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He served as a minister to France in the 1790s and was a U.S. Senator from 1800 to 1803. By 1807, he was considered one of the country’s great elder statesmen. Morris also resided on his family estate in the Bronx, Morrisania. And, like De Witt, Morris became a member of the first Erie Canal Commission.

John Rutherfurd was born into a wealthy landowning family in New Jersey and served as U.S. Senator from 1791 to 1798. Rutherford was married to a daughter of Morris’ half-brother, and this inside connection probably helped him get chosen for the job. Of the three Commissioners, he had the least experience with surveying and planning.

The Commission was empowered in April of 1807 and had four years to survey and plan Manhattan’s rural lands. Their domain began north of the city proper, which would be left as was. Their charge started at the foot of today’s Gansevoort Street in Greenwich Village and then over to Greenwich Avenue, then along today’s East 8th Street, then south along the Bowery, and east to Houston Street. Why exactly this border was drawn remains unknown, but grid plan historian Gerard Koeppel concludes it was influenced by Mangin’s map.

Enter Randel

The Commissioners’ first surveyor turned out to be a dud. They waited a year for him to churn out results. But with nothing to show for it, they entrusted the 20-year-old John Randel, Jr., who joined as the Commissioners’ surveyor in June 1808. Randel had worked as a surveyor for De Witt in upstate New York, demonstrating skill and diligence.

With only three years left on the clock, Randel went to work to capture Manhattan in a bottle, so to speak. He trudged through the farms and woods, up the hills, down the valleys, and through the wetlands. Along the way, he encountered many hazards, including being arrested multiple times by property owners accusing him of trespassing (which will be discussed in the next post).

The Fateful 1811

Questions Unanswered

However, as Randel did his job, the Commissioners sat on their hands. While the trio waited, they could have sketched various plans for the island. There were many questions they could have discussed: Should we include wide boulevards and circles or plaza where they meet? Should we orient the blocks east-west or north-south? What’s the ideal block size? Should we have alleyways in the center of each block?

But as Koeppel documents, the Commissioners dithered. They seemed generally uninterested in the task before them and preferred to be elsewhere, rarely meeting to discuss Manhattan’s future. From March 1810 onward, De Witt and Morris were busy on their canal gig. While there is little direct evidence of their thinking—they did not need to record minutes of their meetings, nor did they—as their April 1811 deadline approached, they had to come up with something.

Cut and Paste

Ultimately, they told Randel to make a map that looked much like that of Casimer Goerck’s Common Land plans, which had created 920-foot-long blocks and 220-foot-long avenues. They would even convert his “middle road” into Fifth Avenue. Their street plan would thus be Goerck’s grid plan writ large—painting Manhattan as a form of cellular automata.

Rather than give the streets fancy names of flowers or Founders, they embraced a utilitarian numbering system. The crystal seed was First and First. The southernmost east-west street would begin with First Street and count upwards. The highest number would stop at 155th Street, some two-thirds of the way up the island. Why did they stop there? Nobody knows. But they figured it might be a while before the population arrived, and future governments could worry about laying out the land.

Several streets would be extra wide—100 feet—starting at 14th Street, then at 23rd, 34th, 42nd, 59th, 72nd, 86th, and every ten blocks from there. Why these wide streets occur irregularly to 86th Street remains one of Gotham’s great mysteries.

Block Sizes

Wider north-south avenues of 100 feet would begin with First Avenue on the east side and count upward going west to Twelfth Avenue along the Hudson River. All blocks were set at 200 feet wide, which means that with 60-foot-wide streets, a north-south walk of 20 blocks equals about one mile. From Third to Sixth Avenues—the center spine of the island—the Commissioners kept Goerck’s 920 feet length. Moving eastward, blocks shrink to the 620-to-650-foot range. West of Sixth Avenue, block lengths were fixed at 800 feet.

Since the Lower East Side juts out a bit—giving it an awkward shape that did not fit neatly into the program—it was assigned “negative” numbers of a sort. Starting from east of First Avenue, the north-south avenues were given letters from A to D, creating what today is colloquially known as Alphabet City.

While the logic of the repetitious grid was nearly 100%, a few spaces in the Commissioners’ plan were peppered here and there for some social purpose. A public marketplace for selling fresh food was proposed in what today is the area around Tompkins Square Park and eastward to the East River. Its location was chosen over a salt marsh because it would be cheaper to buy and drain it.

A large parade ground for troop marching was also proposed in a large plot centered around 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue. (In 1811, the British were still a menacing presence in American affairs; by 1812, war would break out again between the two nations). Broadway would run to the grounds at 23rd Street and stop. A few other smaller parks were dotted throughout the island.

Plain and Simple

Otherwise, there were no expansive boulevards or ovals. It was as much a “plan of no” as anything. It had none of the artistic flair of Pierre L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for Washington DC or the utopian thinking of William Penn for Philadelphia. There was no provision of grand civic spaces for monuments or arranging the city according to some notion of urban beauty or grandeur. And just as important, there was no due consideration for diagonal travel across the island. The city’s ports were along its rivers, and the east-west orientation of the plan seemed designed to facilitate trade.

In short, the Commissioners, with little time and interest in their rights and responsibilities, decided at the last minute: Manhattan will be one large, weirdly proportioned grid—best of luck with that! The idea of 900-by-200-foot blocks is probably the most anomalous street plan in the world—and all because the Common Council told Casimir Goerck to layout five-acre parcels in 1785 (and again in 1795).

A “Q&A” with the Commissioners

The Commissioners were remarkably taciturn when it came to explaining their decisions (probably because they gave the whole thing little thought). They provided a very short document—some 4.5 pages, of which 2.5 are descriptions of their map. Because it’s all there is to figure out their thinking, historians have put the document through what might be called planning hermeneutics, parsing their words for some insightful interpretation.

But let’s turn to their statement to ask them what they thought.

Q: Why did you choose a repetitive grid plan?

A: In considering that subject [we] could not but bear in mind that a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in. The effect of these plain and simple reflections was decisive.

Q: Did you get pushback from Nimbyists as you created the plan?

A: To show the obstacles which frustrated every effort can be of no use. It will perhaps be more satisfactory to each person who may feel aggrieved to ask himself whether his sensations would not have been still more unpleasant had his favorite plans been sacrificed to preserve those of a more fortunate neighbor.

A: Did you consider other types of street plans?

A: If it should be asked why was the present plan adopted in preference to any other, the answer is, because, after taking all circumstances into consideration, it appeared to be the best; or, in other and more proper terms, attended with the least inconvenience.

Q: And why were there so few parks or open spaces?

A: It may to many be a matter of surprise that so few vacant spaces have been left, and those so small, for the benefit of fresh air and consequent preservation of health. Certainly if the city of New York was destined to stand on the side of a small stream such as the Seine or the Thames, a great number of ample places might be needful. But those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan island render its situation, in regard to health and pleasure as well as to the convenience of commerce, peculiarly felicitous.

Q: And why did you create a street plan for the whole island?

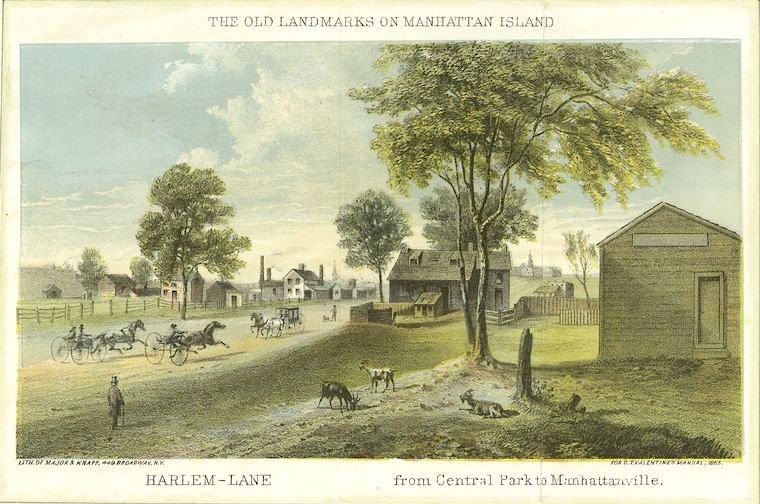

A: To some it may be a matter of surprise that the whole island has not been laid out as a city. To others it may be a subject of merriment that the Commissioners have provided space for a greater population than is collected at any spot on this side of China…. and it is improbable that (for centuries to come) the grounds north of Harlem Flat will be covered with houses. To have come short of the extent laid out might therefore have defeated just expectations; and to have gone further might have furnished materials to the pernicious spirit of speculation.

Evaluating the Plan in History

While there have been many alterations and deviations from the original blueprints, the essential logic has remained (the next post will discuss how the grid plan was implemented). The block sizes and the street pattern have created Manhattan’s unique identity, and which has produced a cottage industry of grid plan debating and argumentation. Some have hailed it as visionary and the Greatest Grid, while others have lambasted it as the worst planning mistake ever made.

The Greediest Grid?

One gripe has been the plan is monotonous and boring. One early 20th century Manhattan historian nicely summarizes this line of thought:

Unfortunately, this plan, although possessing the merits of simplicity and directness, lacked entirely the equally essential elements of variety and picturesqueness, which demand a large degree of respect for the natural conformation of the land. The new plan was entirely deficient in sentiment and charm, and with its gradual development, little by little, the individuality, the interest, and the beauty of one choice spot after another have been swept away; until now, except in Central Park and at the extreme north of the island, scarcely anything remains to remind us of the primitive beauty and the fascinating diversity of natural charms which we know Manhattan once possessed. The year 1811 marks the end of the little old city and the beginning of the great modern metropolis.

And though the plan was supposed to increase air circulation and improve health, one reformer, Egbert Viele, complained in 1865, that it would have the opposite effect:

I know that is generally supposed that when the city is entirely built upon, all that water will disappear; but such is not the case. The very material which is thrown in to cover it up will form a nucleus for its increase, not only retaining a large amount of moisture, but will have added to it the drainings through the animal and vegetable refuse which accumulates in all large cities.

And for much of the 19th century, he was correct, rapid gridding meant filling in wetlands and streams, which would haunt the city by generating vectors of disease.

Finally, another trope was that the plan was simply a capitulation to the tidal forces of the marketplace. By creating relatively narrow streets and large blocks, at right angles, Manhattan, it has been alleged, was to be given away to greedy speculators, who build (or not) based on their self-interest, the commonweal be damned. What nature gave, real estate taketh away.

Republican Triumphalism?

But we also must be mindful of the context. Grid plans had a long record in urban history that can be traced from Greek cities to Roman military bases to Spanish colonial cities to the efforts of Jefferson’s plan to grid America’s farmland to Simeon De Witt’s actions “gridding” upstate New York, including Albany.

Whether you agree with the Commissioners’ plan or not, their city planning ideas did not exist in a vacuum. The American Republic was borne from Enlightenment concepts about the power of human rationality and individuality to improve our collective condition, and to which nature took a back seat to human progress. These ideas along, with the laissez-faire attitudes that were imprinted on the British colony, meant the government had limited powers and resources to shape the landscape according to a grand aesthetic scheme.

By 1807, Gotham was no longer a political city; the Federal and state capitals had been moved elsewhere. The best New York could produce was a plan that encouraged the triumph of the individual spirit. Trade was its lifeline.

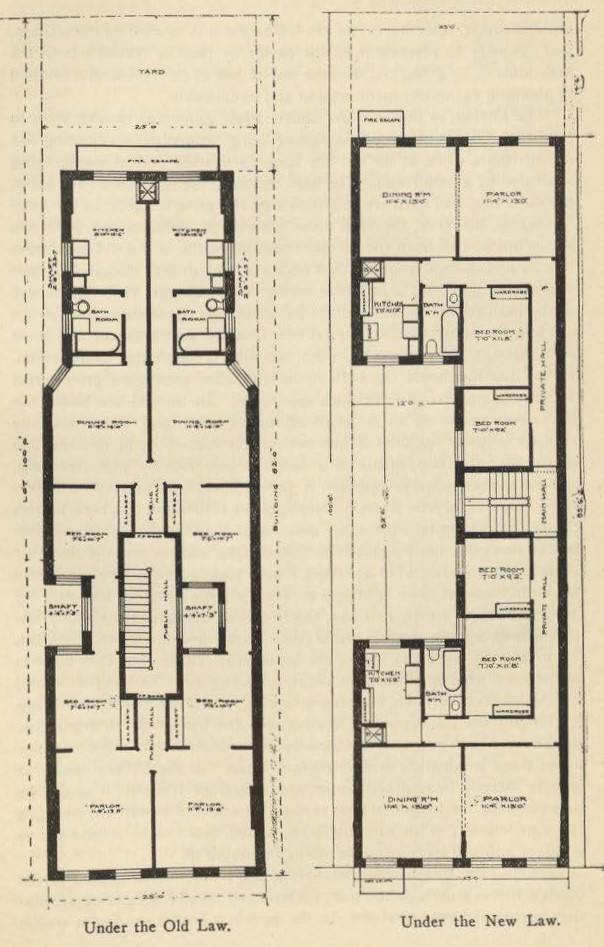

In some sense, the grid plan can also be seen as a project in democratization. The large landholdings of the elite were carved into blocks which were carved up into small lots and were sold to individual households or smaller property owners. It was through the process that brownstones, tenements, and apartment buildings would later rise—holding a population of nearly two million souls by the turn of the 20th century.

Ironically, if the Commissioners had not been so sparse with parkland, there likely wouldn’t have been the pushback that led to the creation of Central Park in the mid-19th century, one of the world’s greatest urban parks.

From Blue to Brick: How Gotham Implemented Its Grid Plan

With blueprints in hand, and the force of law behind it, Gotham now had its street plan. But implementing it as it was designed would be a whole other adventure. It is to this story that we turn in the next post. Stay tuned….

Read Part I of this series on the history of Manhattan’s grid plan here.