Jason M. Barr March 6, 2025

Note: This post is the second of two on the drivers of Gotham’s historically low vacancy rates. You can read Part I here.

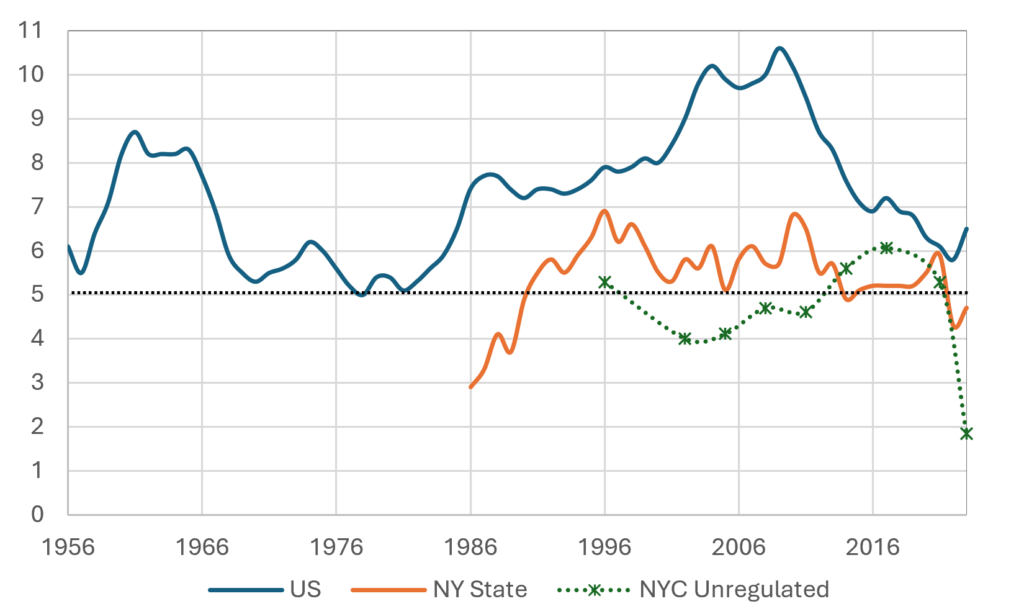

New York’s rental housing vacancy rate is 1.4%—the lowest since 1969. The lack of available housing means that Gotham remains in a “housing emergency”—defined, by law, when the vacancy rate is below 5%.

By this metric, the city has been in a continual emergency since 1943, when rent controls were first enacted. This fact begs the question: Why has the city’s vacancy rate never risen above 5% in over 80 years, and what will it take for New York to free itself from this emergency?

The Theory of Vacancy

Before we analyze New York’s vacancy rates, it’s important to lay out basic concepts. “Vacancy” is defined as the total number of occupiable units minus the total number of units that households occupy. This means that vacancy is determined by the total supply of rental housing relative to the total demand. All else equal, things that raise the number of units will drive up vacancy, while things that increase demand will drive it downward.

Of course, supply and demand are not independent since they are both affected by the price of housing. When prices rise, we expect more supply to be brought online since developers can reap higher returns from new construction. Higher prices will also reduce the demand for units through people living in larger households or by leaving the city altogether (or, implicitly, by not entering).

Over time, when vacancy rates fall below a certain threshold (say 5%), economic forces should create more housing and increase vacancies to a more natural level. We see this phenomenon across the U.S., where average rental vacancy rates have been about 7% since 1956 (across New York State, the average vacancy has been 5.4% since 1986). When vacancies fail to move above 5%, it suggests barriers to new construction.

Housing Supply

The total housing stock is given by the number of new units added to last year’s stock, minus the number of units lost, through demolitions, conversions, or combining units. So, what drives a net growth in the housing stock?

First is the economic climate. When inflation and interest rates are low, more units will be built since housing is cheaper to construct. On the other hand, when construction costs are high—either locally through expensive labor and materials or nationally through supply chain problems or high interest rates—developers are incentivized to provide less housing, all else equal.

The other element is operating costs, which include taxes and maintenance. Again, as these costs rise, it becomes more expensive to provide housing. As a result, current properties are allowed to decline in quality (and some are eventually torn down), warehoused, or switched out of the rental sector, and developers add less new housing because of lower profits.

Rent Regulations and Supply

Additionally, there are building regulations. The more stringent they are, the lower the new housing supply will be because they reduce the return on investment or produce the fear that if market-rate housing is built today, there is no guarantee that the state won’t impose new regulations down the line.

One of these barriers is limits on rent increases. Price caps on units, in and of themselves, reduce vacancy since the lower prices mean building owners are incentivized to provide less housing. At the same time, consumers seek to have more of it–either by staying in apartments that are too big for their current needs and/or by staying in their units longer than they would otherwise so as not to give up their good deal.

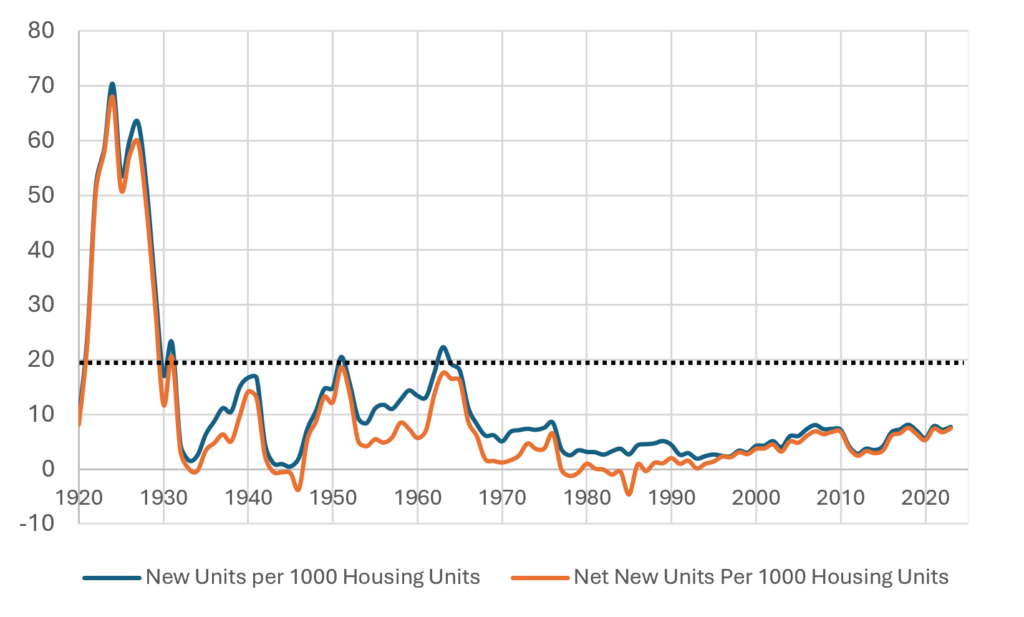

The “lost years”—from 1977 to 1991, when cumulative net housing construction was negative—were driven, in part, by the severe limits on landlords’ ability to raise rents while costs, such as property taxes, were rising. Landlords were squeezed on both ends, and the result was abandonment (and rampant arson).

Zoning

But rent regulations are not the only game in town. In 1961, the city was massively downzoned. These regulations disincentivized developers and landlords from producing the units needed to keep prices and vacancies in check. Had looser codes been in place, it’s likely the city would have eventually built itself out of a crisis.

Housing Demand

The number of units demanded by households, independent of the price, is driven by population growth, household size, and income. Large population influxes and increasing incomes due to rapid job growth will increase the number of units (and square footage) people want while falling household sizes will also increase the number of units needed.

For example, in the 1970s, even as the population of New York was falling, the number of households was increasing as people were more likely to live by themselves or in pairs. As a result, the demand for housing remained relatively constant during the decade. Even during the lost years, demand fell but not through the floor since household sizes were also dropping. The low vacancy rates were not being driven by hyper-demand but by demographic shifts (and abandonment). Today, low vacancy rates are being driven by rising incomes, global demand to be in the city, and falling death rates.

A View of Vacancy: A Look at the Data

So, with these economic theories in mind, let’s turn to the data to get clues on the key question: Why has New York’s rental housing vacancy not risen above 5% in 80 Years?

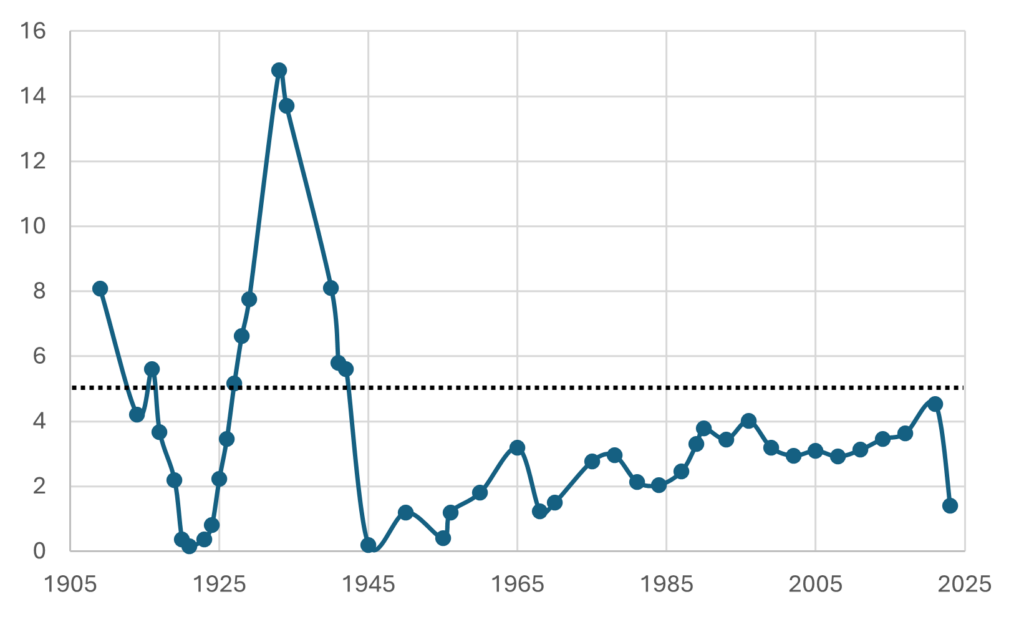

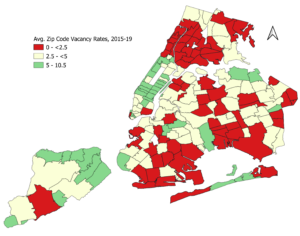

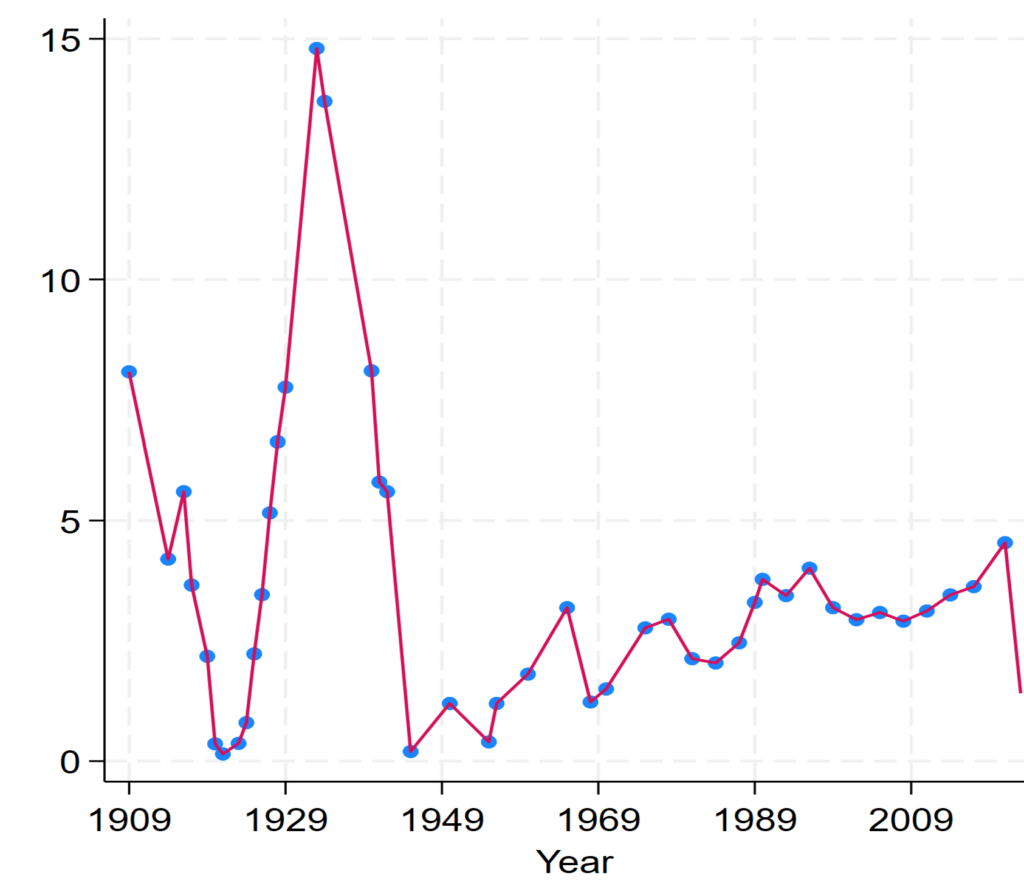

I have assembled two types of data sets to understand the drivers of vacancy rates in New York. The first is annual vacancy rates from 1909 to 2023 and the factors likely to them. The second is a data set with average vacancy rates across zip codes from 2015-2019 and related data that likely drive vacancy across space. (Data sources and results here).

Time Series

Looking at the drivers of vacancy rates over time is good at showing how vacancy is driven by a series of “credits” and “debits”—the respective, economic, demographic, and policy forces that raise or lower vacancy. This analysis demonstrates how the city can use statistical models as guide to adjust the policy levers as vacancies fall. Fluctuations in vacancy are not random. They follow a pattern that can be predicted and, in principle, anticipated.

Of course, economic crises tend to be random, but their impacts are not. In this sense, the City can create an “alert index.” When the economic and demographic forces push the index to a specific value, the government should automatically trigger policies to increase supply, by increasing construction cost subsidies or by relaxing building regulations to get additional housing more rapidly.

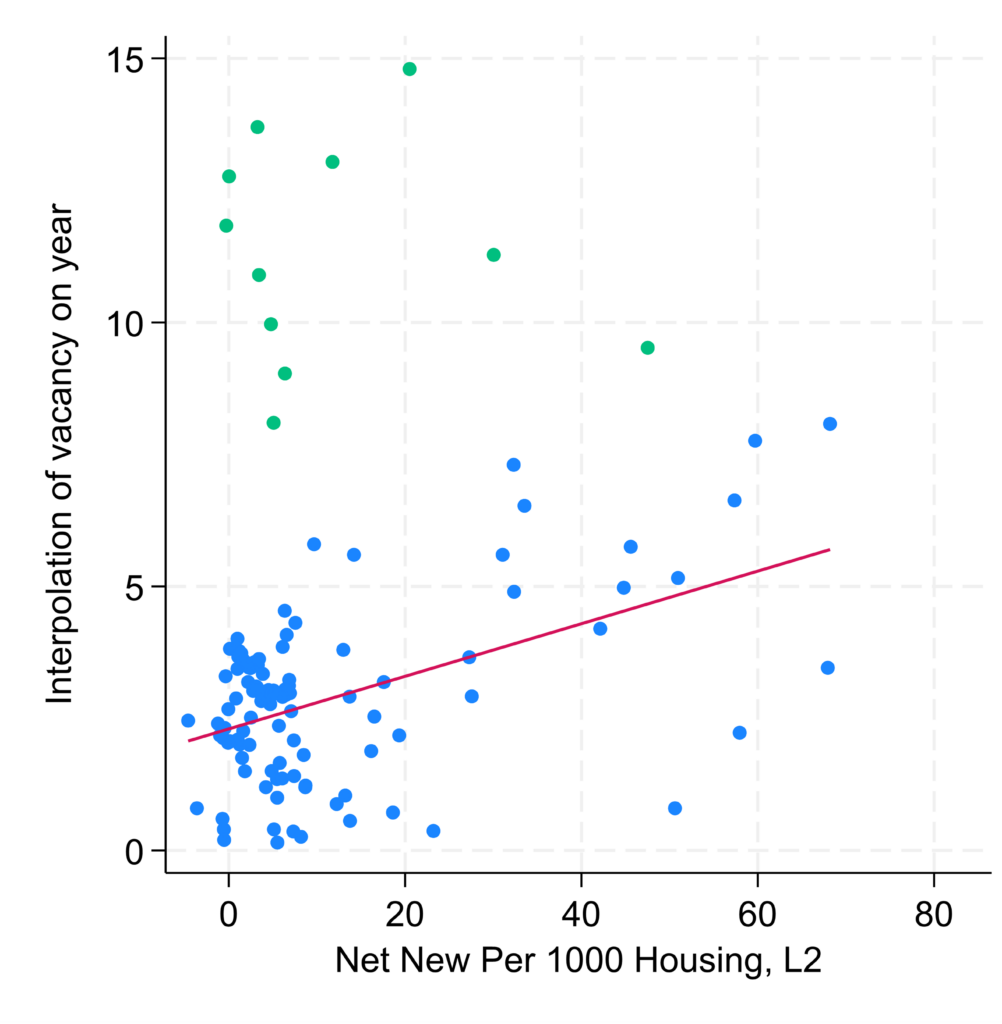

The statistical results also provide strong evidence that there are two mechanisms—one direct and the other indirect—by which vacancy is reduced. The direct mechanism are those things that reduce housing availability, while the indirect mechanism is through the forces that affect new construction, which then, in turn, affects vacancy.

The Direct Mechanism

Net housing supply matters. The statistical results show that, all else equal, a rise in supply of 1% (10 net units per 1000) leads to an increase in vacancy rates by 0.65% – 0.75%. This means that if we start with a 3.4% rate, which has been typical in the 21st century, to get to 5% from new construction, we’d need to raise the annual housing additions rate by four times its annual amount, all else equal. In other words, the city must return to producing new housing at rates similar to the non-Great-Depression or War years in the 20th century.

The rent control years were also bad for vacancy. All else equal, vacancy rates were about five percentage points lower than they would be otherwise. I find a smaller–though still negative–effect of the rent stabilization years (since 1969) on vacancy rates relative to years with no regulations (why this requires further study). When I look at the role of real estate tax rates, I found that as tax rates rise, vacancy falls, suggesting that higher taxes are also causing landlords to reduce the amount of housing they provide.

Just as important is the duel with economic and population growth. For example, I found that each 1% increase in GDP per capita in a given year reduces housing vacancy by 1.6 percentage points, all else equal. In other words, given New York’s place in the national economy, New York feels the housing pinch when times are flush.

The Indirect Effect

Since new construction affects vacancy, what drives new construction? I find that costs matter—when construction costs rise, supply is curtailed. For example, a one-percent increase in building materials inflation reduces the rate of net new units by 1.2 percentage points.

Just as important, the evidence suggests that the 1961 zoning codes have been quite harmful to new supply, reducing the net new housing rate by about 0.7 percentage points (consider that since 2000, the average net new supply rate has been 0.5%). And based on my estimates, the rules indirectly reduced vacancy by about 0.5 percent points lower each year than it would have been if zoning regulations had been more lenient.

Interestingly, I don’t see an effect of rent control and rent stabilization on new construction rates. This is likely partly because new units have traditionally been market-rate units or gained subsidies to offset the loss of income from rent stabilization. In short, the evidence here suggests that rent regulations mostly work to reduce the stock of housing by incentivizing building owners to provide fewer units (or to convert or abandon them).

Death by a Thousand Paper Cuts

Taken together, the statistical results demonstrate what might be called the death-by-a-thousand-paper-cuts method of keeping vacancy low. First, economic growth and falling household size mean vacancy is constantly being pushed downward. Then, when inflation hits, raising construction or operating costs further increases vacancy. But these economic “downward” forces are not being met by an equal reaction on the supply side.

Rent and zoning regulations have worked in roughly equal measure over time to keep the housing supply from responding quickly to economic changes. The rent control years were particularly bad, but today, the main policy effects are coming from relatively higher real estate taxes on apartment buildings and stringent zoning limits across the city.

Across Zip Codes

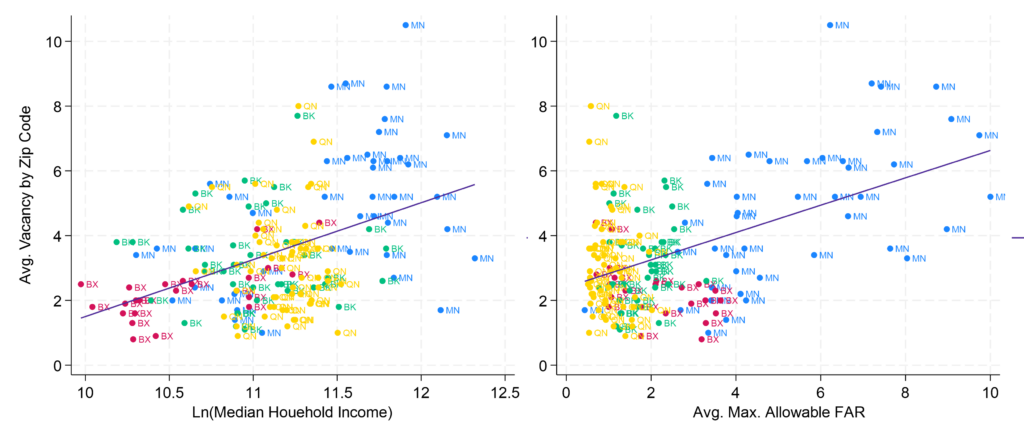

To investigate the question from another angle, I looked at the drivers of average vacancy rates from 2015 to 2019 across New York’s zip codes. This type of analysis is good for examining how zoning and new construction impact vacancy rates, holding demographic factors constant.

The results of this analysis support the conclusions from the time series analysis. Holding population and number of households content, more construction and less stringent zoning raise vacancy rates. But again, both income and population matter. Lower-income districts have lower vacancy rates because there is less construction there and because of lower household turnover.

Interestingly, I did not find a connection between the number of rent-stabilized buildings in a zip code and vacancy rates. This suggests that the drivers of vacancy are more closely linked to income, housing supply, and zoning regulations.

I find that all else equal, a one-point increase in the average allowable floor area ratio in a district yields a 0.7 percentage point increase in vacancy. If this appears low, it is. The reason is because, the data show, that the zoning increases need to be quite generous before they have an impact on vacancy. Based on my findings, the average allowable FAR doesn’t significantly improve vacancy until it hits a FAR of at least five—meaning, a district needs to allow buildings between 6 to 11 floors, on average, to have a meaningful impact on vacancy rates.

What are the Solutions?

Let me begin this section with a key point and one that is strongly supported by the data. The New York City housing market is, like any market, affected by the ebbs and flows of supply and demand. Supply matters, but it must be added to the city at a meaningful rate—and in neighborhoods where it is most needed—particularly in lower-income neighborhoods.

If low rental vacancy is the cause of the emergency, then increasing vacancy should be the focus of the solution. The most important thing the government can do is target neighborhood vacancy rates. Looking at the map above, we see the communities most in need are in the “red zones”—particularly northern Manhattan, the South Bronx, and southern Brooklyn and Queens. In these neighborhoods, the government should employ a combined strategy of providing generous construction subsidies, enacting significant upzoning, and potentially involving itself directly in new housing construction.

There should also be an increase in vacancy decontrol. As vacancies rise through targeted new construction, people will be more likely to leave their old units for the new housing, which will free up lots to be redeveloped or incentivize landlords to upgrade these units or cease warehousing them.

Finally, the City needs to create a master plan that improves transportation, parks, and services as neighborhood populations increase. Giving people confidence that densification will not harm residents’ quality of life is key in getting buy-in to making housing more affordable.

It was Supposed to be Temporary

It’s important to recall that in 1943, when rent control was imposed, it was seen as a temporary expedient to help renters harmed by the dislocations from World War II. Price controls were never meant to be a long-term policy, and the on-going housing affordability problem shows the long-term harm they can cause. It’s time that Gotham builds its way out of a “housing emergency.”

You can read Part I of this post series here.