Jason M. Barr January 3, 2019

Note this is Part II of a series on the economics of skyscrapers. The rest of the series can be read here.

When we think of the world’s tallest skyscrapers, the natural reaction is to insist that they are “freak projects,” built by ego-driven, greedy developers who imposes their will onto a city. And yet, this whiff of conspiratorial thinking exists side-by-side with our fascination with tall buildings. Countless coffee table books—skyscraper porn, if you will—have been published that compare the world’s tallest buildings, and offer dazzling photos and fancy drawings. Skyscrapers are the soap operas of the real estate world; they generate a guilty pleasure that deep down inside we believe are not good for us. But, before we start drawing conclusions, it is important to first itemize the different elements of building height and focus on those that relate to the world’s tallest buildings.

Types of Height

Economic Height

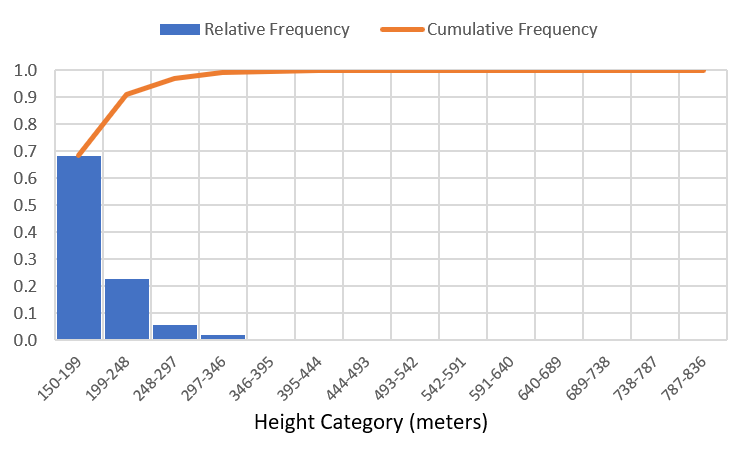

First is Economic Height, which is the height that best balances the costs and revenues from the project, assuming it doesn’t impose hardships on the neighborhood. As a project goes taller, the cost of adding another floor increases at an increasing rate. But adding another floor also increases the revenue. Above the Economic Height, building one floor taller will add a cost that is greater than the revenue it generates. Below the Economic Height, money is “left of table,” since adding a floor will increase revenue more than the costs.[1] Economic Height is the sweet spot and is a useful benchmark because it also represents the most efficient allocation of a society’s resources. As discussed in another post, the height of the majority of the world’s tall buildings are consistent with the notion of Economic Height. But what about the world’s tallest buildings? Does the concept apply to them? We will return to this below.

Developer Height

The next height type is what I call the Developer Height. This is the actual height of a completed building. Developer Height can be taller or shorter than Economic Height. In some cases, height restrictions might force developers to build structures that are economically too short. In other cases, developers may build structures taller than pure economics would suggest, thus making them economically “too tall.”

Symbolic Height

The difference between Developer Height and Economic Height, when the former is larger than the latter, is what I call Symbolic Height. It is that part of the structure’s height that is too tall from a pure profit maximizing perspective. Symbolic Height is meant to convey some kind of message or information to the world. The key point is that if we are going to make conclusions about supertall skyscrapers, we need to more fully analyze the causes and consequences of Symbolic Height.

Vanity Height

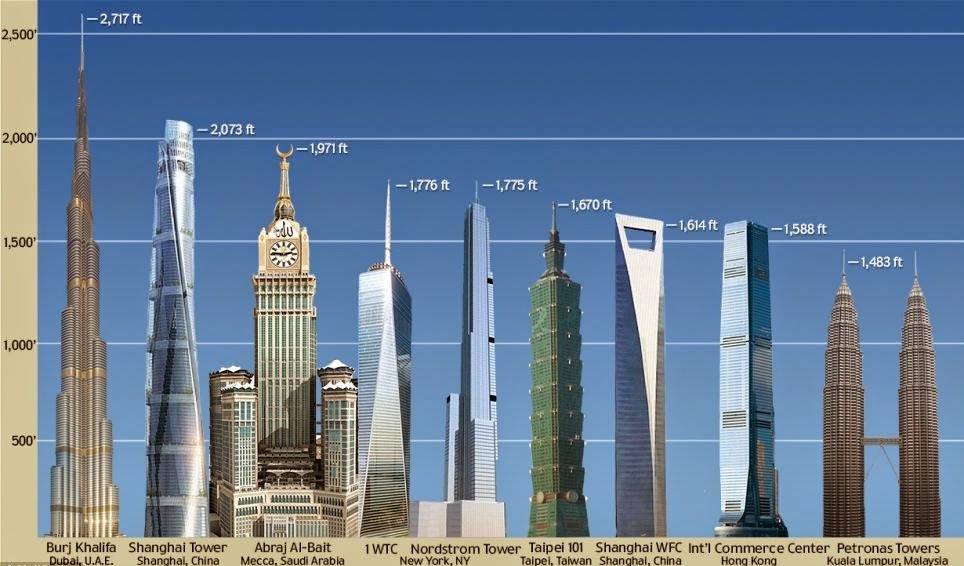

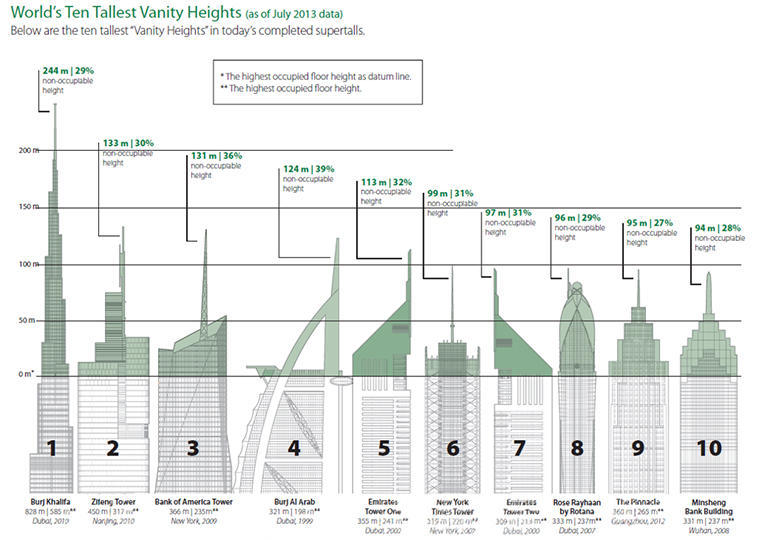

But, before we proceed, we need to break down Symbolic Height a little bit more. In 2013 the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) introduced a new concept, Vanity Height, which is the difference between the height of the structure and the height of the occupied floor. Many skyscrapers, especially among the supertalls, have spires and antennae that are not usable space.

I would argue, that from an economic point of view, what matters is not Vanity Height per se, but rather that part of Symbolic Height that remains after removing the Vanity Height. From a resource allocation question, how much of the floor count is “too tall” from a socially beneficial perspective? Adding spires or non-usable space simply to stand out does not strike me as inherently an excessive use of the world’s resources. These spires may naturally emerge as architectural elements that at, relatively low cost, allow the building to stand out. Being so high in the sky and quite thin, they are not likely to add to traffic congestion on the street or excessive shadows, and they may make the structures more pleasing and marketable.

Furthermore, some Vanity Height is necessary because plant and equipment and wind dampers are often placed on the top floors. Then there are antennae, which, while giving the buildings a height edge, also perform a useful service. The rest of these “vanity” decorations are architectural spires. In some cases, like One World Trade Center, we know there was a non-economic purpose at work, since the spire was used to bring the building height to 1776 feet. But in other cases it is not so clear. The existence of Vanity Height does suggest that developers and architects are interested in the “iconification” of their structures (and that there is a competitive element to this).

Theories for the Drivers of Symbolic Height

A common failure in the thinking about Symbolic Height is that people first observe the height of the building and then draw conclusions about the forces that generated it. Yet it’s nearly impossible to get into the heads of developers to know what they are thinking. Because these buildings are so large and visible, our brain is naturally drawn to infer that they are arrogant Towers of Babel. But this is backward logic.

Scientific investigation, including in the social sciences, is the process of offering theories, which generate testable hypotheses, which are then supported or not based on rigorous tests or experimental evidence. To simply say that the world’s tallest buildings are too tall based on casual observation or loose correlative exercises is nothing more than a leap of faith or faulty reasoning.

What are the theories about why supertall and megatall buildings exist above the heights predicted by economics? Some are theories are “nefarious,” others benign, and while others productive. Here I list nine, which can be divided into four categories: “economics,” “the selfish developer,” “the selfish politician,” and “urban growth strategy.”

Theory I: Economics

It might simply be the case that economics is on the side of the developer so that a supertall structure has little or no Symbolic Height. The world’s tallest building may naturally emerge from a “perfect storm” of factors that produce tall buildings in general: having a large lot in a central location, combined with a high demand for building space, and particularly low construction costs. Or, in some cases, the Economic Height is sufficiently tall that adding Vanity Height has a low enough cost to perform the additional function of advertising the building, city, or developer. In some cases, a large international corporation may be willing to pay for naming rights or to guarantee a minimum rent because of the advertising it brings to the company itself, which can be a useful signal to consumers about the quality of the company’s product.

“Selfish Developer” Theories

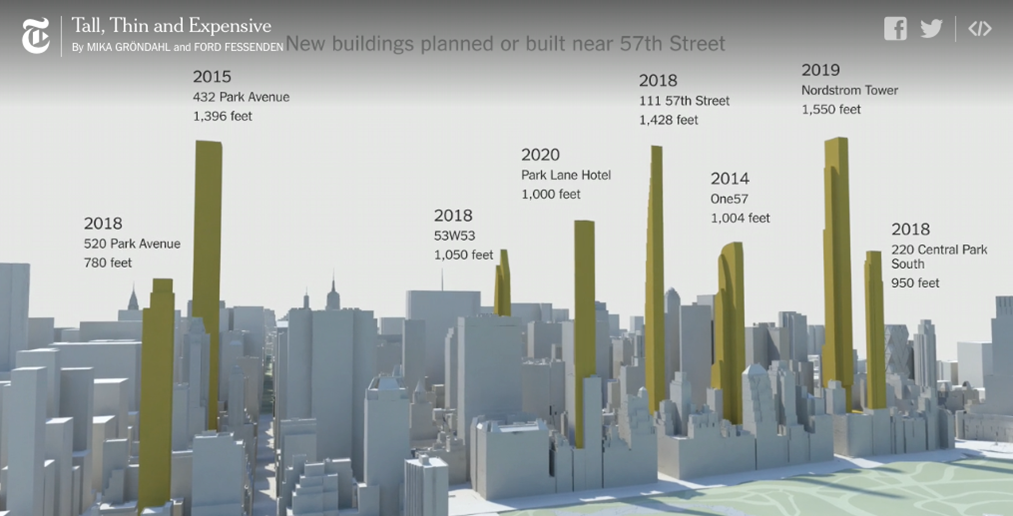

Theory II: The Ego Prize and Developer Competition

In the economics literature, one of the most-read papers on skyscrapers is by Helsley and Strange (2008). They observe that throughout the world, a city or region’s tallest building is much taller than the next tallest one. Based on this observation, and from readings from the popular press, they conclude that this suggests that developers aim to satisfy their egos by claiming the “prize” of “tallest building.” They then generate a mathematical model where two developers compete against each other. In equilibrium, a too-tall building can result. This model suggests that the outcomes we observe are theoretically possible, but it does not prove or disprove anything about the true motivations of builders.

Theory III: Easy Credit, Irrational Exuberance, and Moral Hazard

Another theory that looms large is that during times of easy credit, builders succumb to irrational exuberance. Banks and other financial institutions are so eager to lend money, that developers are emotionally compelled to build while the spigot is open. In this case, developers construct a region or world’s tallest building knowing that if the project loses money, the creditors (or society at large) will bear the cost of failure. Easy credit leads to a moral hazard: risk-loving, ego-driven developers are subsidized by the credit markets to go too tall.

Theory IV: Corruption or Legal Ambiguities

Demand Side

Corruption can take on many forms. In the case of Donald Trump, there is evidence that the demand for his buildings is due, in part, from those who want to launder money. It may be that the mega-wealthy are willing to pay higher than market rates for units to have a safe place to park their ill-gotten gains. In this case, developers are responding to the favorable economics, but they ask few questions about whether the funds were legally obtained.

Supply Side

Developers in some countries may bribe political officials to get tax breaks, low-interest loans, or artificially cheap land in the central cities. Thus, by illegally lowering the costs to construction, the economics of supertall construction becomes profitable. Another version of this is that builders can use clever strategies to interpret the law to their advantage, and in way that is not strictly illegal but is morally ambiguous. The real estate company of Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in law, is known, for example, to use the Federal Government’s EB-5 Program to get access to cheap financing for luxury towers in central locations. The program was designed to promote the redevelopment of economically depressed areas and was not intended to subsidize luxury towers.

“Selfish Politician” Theories

Theory V: Bread, Circuses, and White Elephants

This theory says that autocratic rulers use supertall skyscrapers to further their political agendas. By building them, these leaders provide symbols of their power, or seek to give pride of place to residents, who need justification or reasons to legitimize their autocratic leaders’ rule over them. Or, perhaps, autocrats use large skyscrapers as projects to put citizens to work or to distract them from their own oppression.

Theory VI: Political Career Promotion

A somewhat more benign version of the greedy politicians theory is that local officials use skyscrapers to advance their careers. In China this appears to be common, since the Communist Party makes decisions about who gets leadership positions within the various levels of government. In this case, promoting skyscrapers is a visible means for a local leader to signal that they can “get things done,” so they can then be entrusted with greater responsibilities or placed at a higher level in the government.

Urban Growth and Development Theories

Theory VII: Urban Growth and Neighborhood Formation

In the 21st century, the world’s richest nations manufacture mostly services and intangible products. These are created by high-skilled workers who need to cluster together in large cities. The economic forces of agglomeration mean that larger cities have an edge over smaller ones. Governments throughout the world, recognizing this, might use a supertall building as a way to “spark” these forces of city growth. By building (or subsidizing) a landmark structure, local or national governments attempt to create business clusters that will draw people to that neighborhood and make it more productive.

Theory VIII: Tourism

Nothing is more fascinating than being on a viewing deck high in the clouds. People pay good money for a vertical road trip to the sky. A ticket for the observation deck at One World Trade Center is $34 (and for $74 you can upgrade to the “luxury” experience). Local leaders may subsidize a too-tall building because it draws tourists, which increases employment and economic opportunities for the locals. Visiting these icons creates pleasure and a memorable experience.

Theory IX: The Economic Map

The fastest growth in the world’s cities are in developing countries. Political leaders there realize that to promote their economies, some form of advertising helps to turn the world’s eyes toward them. This leads to greater foreign direct investment (FDI), tourism, and improved employment opportunities. Because skills and services generate the highest paid work, countries seek to increase the prospects of the urban-based services sectors, including their financial sectors. By building a too-tall structure, local officials seek to advertise the city, and increase global confidence in the place.

The Evidence

What does the evidence suggest about which theory best applies? This will be taken up in the next post.

Continue reading. The rest of the series can be read here.

—

[1] Note that Economic Height is a theoretical concept because of the “lumpiness” of construction, the uncertainty about future revenues, and that we hold lot size and other things constant–meaning that building height is the only decision to be made. Lumpiness is due to the fact that there are thresholds when, if passed, make the costs can jump significantly, such as the need to add a new elevator shaft.