Jason M. Barr August 8, 2022

Stefan Al is the author of Supertall: How the World’s Tallest Buildings Are Reshaping Our Cities and Our Lives (Norton, 2022). Al earned a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from the University of California, Berkeley. He is a practicing architect and has taught at Virginia Tech, Columbia University, Pratt Institute, the University of Hong Kong, and the University of Pennsylvania.

About Supertall

JB: Regarding your new book, Supertall, what is your main argument, and what are the key ideas that you want readers to come away with?

SA: By 2050, 2.5 billion more urbanites are projected to be living in cities. In addition to new housing, this urban drive will require a massive increase in city infrastructure, including roads, sidewalks, parks, and transit, as well as city sewage, water, and power lines. This is like building a new New York City every single month for the next thirty years. If we were to build sprawling Phoenixes, we would waste a lot more energy related to transportation and twenty times more environmental land. We don’t need to tread so hard across the earth if we can rise into the sky.

While high-rise living may not be for everyone, many people actually prefer being in central cities, close to offices, restaurants, and transportation hubs. High-rises can be built in these locations. The more viable urban centers we have, the less our cities have to sprawl.

Skyscraper Innovations

JB: What do you see as the key technological innovations that have allowed buildings to go taller and taller in the 21st century?

SA: With new manufacturing technology and the widespread availability of software simulations for wind and structural loads, it is becoming easier to make structures more material efficient. Structural members, like steel bars and concrete columns, used to be predominantly straight. Now, 3D printing can print materials in any shape and make custom molds for more elaborate concrete forms. Machine-aided manufacturing enables designers to bypass blueprints and communicate directly with machines, allowing more complex forms, such as curvilinear shapes optimized to reduce wind vortexes that the very tall buildings would create. With a wider palette of shapes at their disposal, engineers can also devise structures that more naturally and efficiently transfer horizontal forces to the ground. With less weight dedicated to structures, the building itself can become taller.

Rise of Skyscraper Heights

JB: What is driving or propelling this movement toward taller and taller skyscrapers?

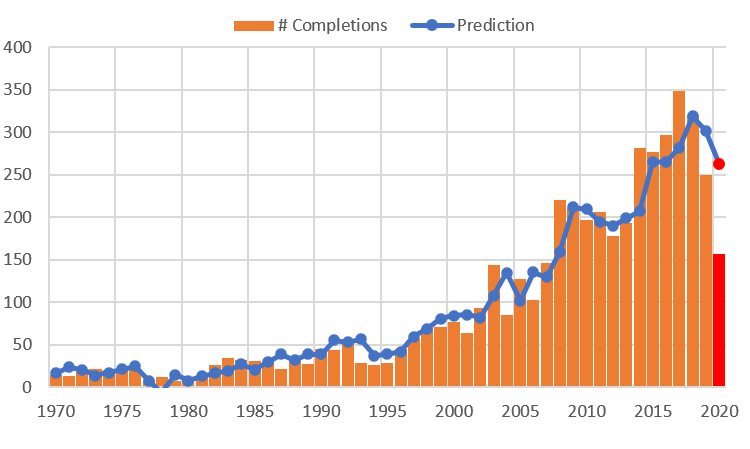

SA: Rapid urbanization has proved to be a major tailwind for skyscrapers, particularly in Asia. The twenty-first century is the first urban century. Never before has more than half of the world’s population lived in cities, attracted by the many and diverse opportunities of urban life. Some countries have even decided to base their national policy on the positive relationship between urbanization and economic growth. China has added roughly half a billion people to its cities. Not surprisingly, it has the world’s most skyscrapers.

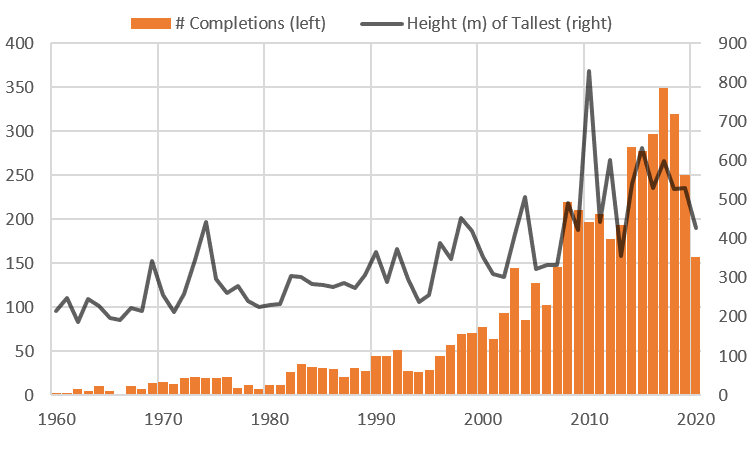

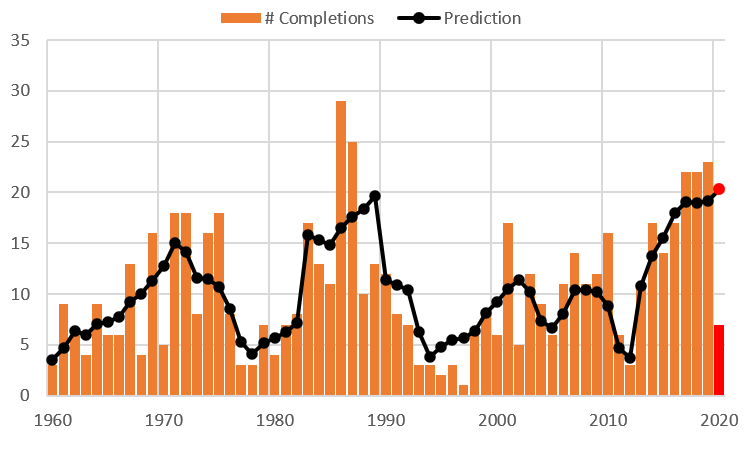

JB: Relatedly, why do you think there has been a massive growth spurt in the number of skyscrapers (say buildings 150 meters or taller) around the world in the 21st century?

SA: What is surprising is that skyscrapers are even altering historic cities previously inhospitable to urban growth. For three centuries, the skyline of London was defined by St Paul’s Cathedral, with its silhouette of a dome and spires. Then, in the 2000s and 2010s, more unusual and often taller skyscrapers came in, crowding the skyline with ingenious shapes that earned them their nicknames, including the Gherkin, the Walkie-Talkie, and the Cheesegrater. In the case of London, new social preferences and the desire for economic growth helped loosen planning restrictions that new skyscrapers faced.

Skyscrapers and Cities

JB: How do you see this growth spurt as affecting cities (either for good or for bad)?

SA: Skyscrapers can have negative impacts on cities, such as increased traffic congestion, a lack of human scale, and restricted views. But with good planning, these problems can be minimized. Even more, when done well, cities can use high-rise development as an opportunity to improve the quality of life for residents. For instance, a thoughtful approach to high-rise development makes it possible to increase green areas, improve public transit, and enhance a city’s vibrancy. Singapore’s LUSH incentives, or “Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-rises,” illustrate how policy can help promote a new generation of “green” skyscrapers, with tall buildings integrated with greenery. Hong Kong shows how to integrate subway stations in high-rise complexes, making it perhaps the world’s best example of Transit Oriented Development. And Vancouver’s “tower and townhouse” model — slim residential towers on a mixed-use podium often containing townhouses — illustrates how to minimize the impact of tall buildings on views while offering pedestrians a human-scale pedestrian experience.

Skyscraper Controversies

JB: Why do you think skyscrapers, especially very tall ones, have become so controversial over the last decade or so? And what might be some ways that cities can address these controversies?

SA: One of the reasons is a reaction to novelty. Very tall towers can be considered “too tall” in proportion to their surroundings. Even the Eiffel Tower, during construction in 1887, was despised by the city’s elite as “a dizzily ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack.” The city seriously considered demolishing it and selling it as scrap metal. Gustav Eiffel himself erected an antenna and financed wireless telegraphy experiments to prove the hollow tower’s utility. With the French military recognizing the tower’s newfound usefulness, a Parisian committee with authority for the structure’s fate only reluctantly let it stand. “One would wish it were more beautiful,” the committee stated.

“Quid pro quo” is one of the lessons here. The Rockefeller Center offered New Yorkers more than a collection of tall buildings to look at but also a remarkable public plaza to enjoy. The Midtown East rezoning in Manhattan offers developers more buildable floor area if they contribute to the public good through transit improvements, such as in the case of the One Vanderbilt tower, which contributed a pedestrian plaza and transit hall.

The Future of the Skyscraper

JB: What is the future of the skyscraper?

SA: For environmental reasons alone, the way in which we design our tallest buildings has to change. Architects are bound by a kind of “Hippocratic Oath” for the public realm and environmental stewardship. Instead of just thinking of about how to get taller-appearing structures, they should also aim to create buildings with smaller environmental footprints.

We need to recalibrate the race for the tallest building. We should aim for buildings to be the greenest, with the most landscaping, and the fewest carbon emissions. We need skyscrapers to generate the most renewable energy, produce the most food, and promote the healthiest environments for residents with the most biophilic benefits. We need tall buildings created with their entire life cycle in mind and to be disassembled in the end. We need the most resilient buildings able to withstand the ravages of climate change with not only practical design but also nods to aesthetics and beauty.

The good news is that many energy-efficient technologies and renewable-energy solutions are commercially available today and are already being applied. Renewable-energy supplies, cross-laminated timber, prefabricated modules, and super insulation are making a positive impact. Now we need a lot more. Despite advances in artificial intelligence and robotics, the built environment is still mostly a brick-and-mortar industry, capital-intensive, and locally fragmented. It tends to lag behind. The vast majority of buildings will become greener only if regulations both force and incentivize them to do so.

The Future of Cities

JB: You have a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning and you also practice as an architect. Given your background, what do you see as the main challenges that cities face in the 21st century?

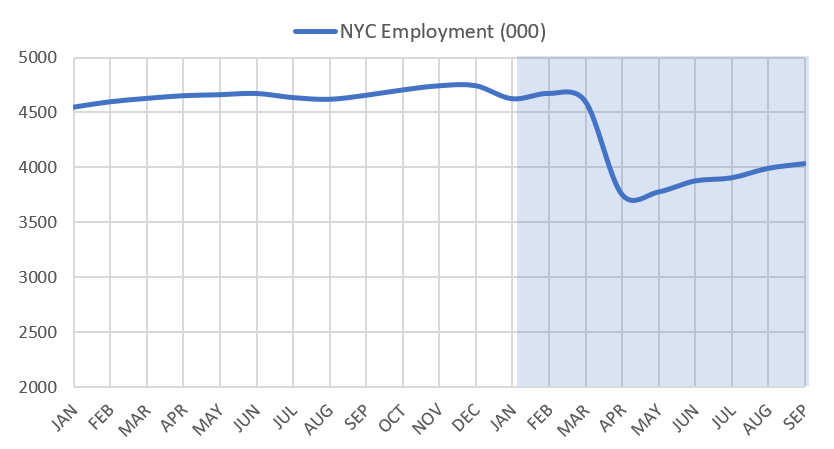

SA: Climate change, urban population growth, and housing unaffordability are already impacting city life. The challenge is how to build up our cities to house more people, how to build more sustainably and equitably, and how to build to absorb the shocks that will come from the increasing occurrence of extreme weather events such as flooding and heat waves.

Climate Change Adaptation

JB: You also have a book Adapting Cities to Sea Level Rise: Green and Gray Strategies. What are the key ideas in this book? Do you see cities employing the strategies in your book? If not, why not?

SA: Growing up in the Netherlands, a country that for centuries has fought the ocean, I have long admired its holistic solutions to flood protection. However, after several flooding events elsewhere, such as Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, I witnessed the building of new sea walls that obstruct people’s views and access to the waterfront. Instead, in my book, I argue for flood protection approaches that are nature-based, integrated with the public realm, and sensitive to local conditions and the community. This way, flood protection can also benefit communities and environments in other ways.

For instance, building flood management infrastructure in urban areas can be particularly difficult in dense cities where land is scarce. Fortunately, recently several innovative solutions have addressed these problems by integrating flood solutions into the public realm and with urban uses. These include the multi-functional flood defenses in Rotterdam. The Dakpark, Dutch for “roof park,” is a dike that also includes a retail and parking structure and a park.

New York is considering several such strategies for the south of Manhattan.

♣

Continue reading other Q&A blog posts in the series here.