Jason M. Barr October 22, 2020

Pleasure or Pain?

One of the biggest complaints about new construction is that it is harmful to the quality of urban life. For example, architecture writer, Justin Davidson, says that “shiny towers are invasive species and they are choking our cities and killing off public space.” Other critics charge that new, taller buildings don’t mesh well with the older urban environment. High-rises, they argue, destroy the “human scale” and make cities less satisfying. Supporters of this view see neighborhoods like Manhattan’s low-rise, but dense, Greenwich as the ideal. In some respects, I don’t disagree. Strolling through Greenwich Village, one feels a kind of urban umami, an almost unquantifiable sense of pleasure (or “deliciousness”). The old brick townhouses on narrow tree-lined streets offer the pedestrian a kind of nostalgic warmth or calmness.

The belief that newer buildings generate negative emotions is likely driving our current land-use policies. Suppose you feel that taller buildings are inherently ugly, stultifying, or emotionally oppressive. The natural response is to demand that city officials limit what can be built. This is exactly what big cities, like New York and San Francisco, have done—they have created a web of zoning and building restrictions to slow down new construction.

Urban Growth versus Real Estate Restrictions

And yet, the very thing that allowed these cities to become successful and house millions of people, and the companies they work for, was to grow their real estate stocks. If economic growth causes a city’s population and business activity to swell, but is unable, through zoning restrictions, landmarking, or general NIMBYism, to expand to accommodate them, residents are simply cutting their nose to spite their face.

Economic growth without real estate growth leads directly to rising housing prices, greater income inequality, anger and frustration from gentrification, and lower future job opportunities. It turns the city into a kind of game of musical chairs—where one person wins only when someone else loses. A substantial body of research demonstrates that new construction lowers housing prices and allows a city to maintain its growth trajectory of growth and vibrancy.

And so, we have a 21st-century paradox—urban growth drives people to limit urban growth. How can we resolve this paradox? More specifically, how can we make inroads on the issue that people think that new buildings are ugly and emotionally oppressive? How can new structures bring joy and utility to both the occupants and city dweller alike?

Measuring Oppression

Over the last few years, social scientists have tried to understand how building form can influence our emotional sense of peace or unease. This research offers some promising leads. A strand in this vein was begun by researchers in Japan in the 1970s, but the work has been revived using modern social scientific and computing methods. The original researchers used the Japanese word, 圧迫感 (appakukan), which translates into “to feel oppression” or “to feel overwhelmed.” And they wanted to know what elements of streetscapes generated appakukan.

Simulated Streetscapes

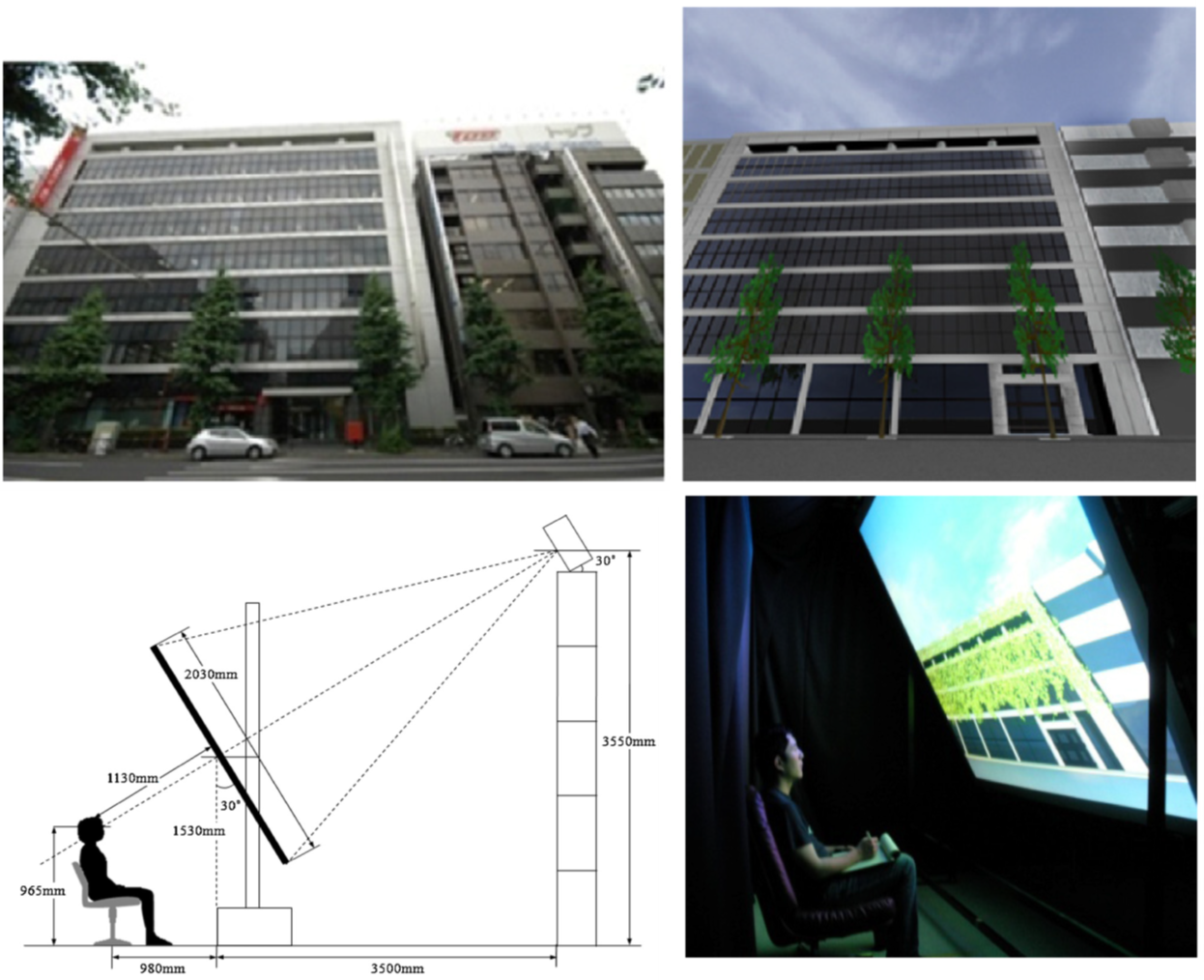

A 2012 study, “Measuring Oppressiveness of Streetscapes,” tries to recreate, in a laboratory setting, the perspectives of pedestrians viewing a high-rise from across the street (although, in the lab, they are sitting in a chair). The authors began by taking a picture with a fisheye lens of a building on Hongo Street, in a dense residential neighborhood in central Tokyo. The choice of camera lens is an attempt to simulate the actual visual perception of the human eye. Next, they render the image into a computer-generated one. This allows them to alter, add, or remove features one a time.

Then they “covered” each image with regularly spaced dots (like regularly spaced points along “latitude” and “longitude” lines). They then counted the number of dots that fall on the building, on the sky, and other features, such as trees. In this way, they have very specific measures of what fraction of the fisheye/human eye view is taken up by different elements that a typical pedestrian might see.

Next, they brought subjects (mostly students of architecture and urban planning) into the laboratory and had them view versions of the simulated imagines. Some had taller buildings; others had more open space; others had substantial tree coverage, and so on. Each of the subjects was exposed to 48 images and asked to fill out five questions per image. The survey asked subjects to rate on a scale of 1 to 7 their perceptions of oppression, openness, and pleasantness.

In short, they found a strong positive correlation between the response to the oppression question and the height of the buildings. But they found that this oppressiveness response was moderated to some degree by adding tree coverage on the street front. Finally, from their results on the relationship between the oppression question response and the quantitative measures of building and tree density, they create a formula, to measure net streetscape oppression. In theory, this formula can then be applied to any building or architectural rending to assess its likely impacts on people’s emotions. (A follow-up study for buildings Iran further seeks to refine this formula.)

Out on the Street

In 2014, the authors published another study, “Investigating Oppressiveness and Spaciousness in Relation to Building, Trees, Sky and Ground Surface: A Study in Tokyo,” using the same methodology. But in this case, their focus was on having subjects (again architecture and urban planning students) observe actual buildings on the street and fill out a survey about how the views felt. They then looked at the responses versus their measure of building, tree, and sky coverage, which, again, were measured from fisheye photographs of the respective views. Here they find that after controlling for the tree, sky, and ground area coverage, the building coverage variable was statistically insignificant regarding the oppression question. This suggests that people’s perception of unease from building form is moderated by the context in which it appears.

In a similar style paper, “Exposure to High-Rise Buildings Negatively Influences Affect: Evidence from Real World and 360-degree Video,” another group of researchers had two sets of study participants looking at buildings in London. One group was sent to directly view the Leadenhall Building (48 floors, 2014) and then take a quick walk to view an older three story-brick building at the rear of St. Helen’s Bishopsgate Church. Each participant viewed the structures for five minutes and answered questions on oppression, openness, and pleasantness. Another test group in Canada viewed the same scenes with special 360-degree headgear and answered the same set of questions. In addition, all the study participants were given a wearable device to measure heart rates, body temperatures, and other physical measures of emotional responses

They found that while participants, on average, felt the shorter building was more pleasing, there was no statistical difference for the specific question about oppression. The shorter building was preferred, on average, in large part due to the openness of the scene. However, the wearable devices did not indicate any physical response difference between the two views, which suggests further work is needed in exploring emotional perceptions versus actual emotional responses. Interestingly, they found very similar results among the London and Canadian subjects, indicate that either in-person or simulated methods are useful.

The Pros and Cons of this Work

The type of research has both pros and cons, however. On the plus side, it offers a way to conduct highly controlled experiments to better understand people’s emotional responses to different streetscapes. The environment can be changed one item at a time to better isolate cause and effect from what are usually busy scenes. Furthermore, the work can tie individual responses to a quantification of these feelings to generate usable formulas. In principle, they can help guide architects, planners, and developers on how their projects may be perceived by pedestrians.

There are, however, reasons to be cautious when interpreting the results. First is that most of this research was conducted with students majoring in architecture or urban planning. This is hardly a representative sample of society, both because they are younger, and because there might be something about either their training or views about cities that make them respond to questions in ways different from the population at large. Second is the study design. In the name of controlling the precision of the experiments, they all involve a degree of unnaturalness. Participants are asked to sit or stand still for five minutes while staring at buildings or images of buildings and reflecting on their emotions. This is not the typical experience of urban pedestrians.

Furthermore, given that the subjects are viewing only one or two specific buildings at a time, it’s hard to know if the responses are due to the building’s general features or to the specific structures, which might be seen as particularly ugly or extreme in and of themselves. Additionally, if respondents suspect, even unconsciously, that the investigators want certain responses, they may try to answer those questions in that way. This is not to say that researchers give away information about their beliefs, but the nature of questioning can subtly influence participant’s responses, especially if a question is asking you how oppressed you feel when viewing a tall building.

Lastly, each study has several different survey questions, and it can be difficult from these to make sense of what they all mean when taken together. Some studies find taller buildings generate high oppression ratings, while others do not; while yet others find the oppression rating is correlated with building height, but the finding goes away after controlling for other factors.[1] In short, more work needs to be done to see if this area can produce some generalizable results that can produce precise and insightful predictions.

Computer Vision in Economics

This discussion also suggests the need to study the issue in other ways beyond psychological surveys. Another parallel approach is within economics. Here, economists have used computer programming/machine learning methods to evaluate the “looks” of buildings. Computer software and statistical methods applied to Google Street View images can categorize the different image features in a method known as Computer Vision. The quantification of these features can then be paired with measures of well-being.

Valuing Curb Appeal

In a recent study, “Valuing Curb Appeal,” the authors determine a numerical measure of a house’s “curb appeal” for nearly 90,000 free-standing homes in Denver, Colorado. First, they generate a curb appeal rubric, which is a checklist of elements about a house’s exterior and lot, as viewed from the middle of the street. Next, they download images of the property from Google Street View.

After that, they assign curb appeal scores (from 1 to 4) for a small sample of images based on the rubric’s underlying results. For example, Class 1 houses (the lowest curb appeal) have broken concrete, overgrown or no lawns, etc. Class 4 properties, on the other hand, have extensive landscaping and fully manicured lawns. Next, they “train” the computer algorithm to recognize the features of the property and assign them curb appeal scores. Then they run the algorithm on all of the properties in their data set to get scores for each one.

Lastly, they perform the statistical (regression) analysis to see how the curb appeal score correlates with housing prices. On average, they find that an improvement from one category to the next, say going from a 3 rating to a 4, is associated with a 2% bump up in prices, holding property size and other housing and neighborhood features constant. In short, they come up with a way to measure the value people place on having a house that is more pleasing to look at.

Curb Appeal in Boston

A similar study from 2018, “Computer Vision and Real Estate: Do Looks Matter and Do Incentives Determine Looks,” uses Computer Vision to quantify the external features of over 16,000 properties in Boston. The authors have the Computer Vision software recognize some 1024 features (such as colors and shapes), and then they reduce this list (using principal components) to 100 elements. Unlike the paper above, these authors only look at how these features as a whole correlate with housing prices and do not attempt to investigate the specific nature of them individually.

The key result of their work is that Computer Vision categories can help better predict sales prices than without them, and it strongly suggests that appearance improves home buyers’ well-being. Future work can expand the analysis to identify the specific coded features that are preferred or disliked, which might include housing color, housing shapes, and the degree of open space.[2]

The Pros and Cons of this Work

Computer Vision and machine learning software offer great potential in helping us to understand what residents find soothing and what they find distressing. Like the psychological studies above, these techniques allow for matching building elements to measures of well-being, and thus, in principle, one can use Computer Vision methods to determine a formula or rule that can guide architects, developers, and planners about what kinds of building and lot features will enhance the “umami” of the neighborhood.

The two research papers discussed here specifically tie their measures of “curb appeal” to housing prices. Prices are a good measure to use because housing sales data are widely available, and they are a convenient way to ascertain what people value. However, using prices to assess psychological well-being or distress can be problematic because houses are bought for multiple reasons, including as investment, and for shelter as well as psychological fulfillment. Thus, the curb appeal measure may be picking up the value of one or more of these elements.

Regarding investments, people buy houses with the expectation that they will rise in price. The price of a home today is, in large, part determined by its expected future value down the road. Curb appeal may indicate stronger investment reward potential, regardless of whether the new owners like those features or not. If lawn gnomes, for example, are popular because people think they bring good luck to the house and its occupants (and hence make it more valuable), despite them being ugly, a buyer might pay more for a house with lawn gnomes

Second, homes are shelter. Curb appeal might mean “good bones” and lower maintenance. Thus, home purchasers might use curb appeal as an indicator of the home’s quality and assume that it will not need major repairs any time soon. And finally, curb appeal or lack thereof may indicate the degree of emotional oppression or pleasure. The point is that price effects from curb appeal may not be directly used to infer streetscape satisfaction. In this regard, more work is needed to tie Computer Vision to psychological studies by mapping Street View images to other measures of emotional satisfaction.

The Policy Implications

The key reason to discuss these research papers is that if we can determine formulas or guidelines for streetscape “umami” versus appakukan and that the real estate community employ them, it might give residents more confidence in new construction. People want to feel that the changes they see around them are helping to contribute to their life-satisfaction or, at least, are not making things worse. Imagine a kind Rip Van Winkle scenario. A person purchases a home and falls asleep for twenty years, but when she awakens, the neighborhood is immeasurably improved in aesthetics and vibrancy. This is what we want to shoot for. And perhaps these new social science research methods can pave the way.

But it is vital that these formulas or rules, once discovered, are be implemented by government fiat. Housing markets need the flexibility to adjust neighborhood housing stocks based on the demand. Rules today may no longer apply tomorrow or may be found to have unintended consequences that need to be rectified. Any policy that uses this research should use incentives in some way so that developers consider both the costs and benefits of urban umami formulas.

For example, if people are not burdened by tall buildings that have a significant degree of open space up high, then setback rules should make buildings gets narrower as they get taller. Since people enjoy trees on the streets, new projects that provide (native) street trees should get floor area bonuses, for example.

And finally, any formulas or findings from this research needs to be strongly validated and tested in real-world settings before being widely applied. Starting in the 1960s, for example, New York’s zoning rules gave floor area bonuses for developers who provided open plazas. This thinking was based in the belief that pedestrians like open space and need more of it. As it turned out, follow-up studies on these spaces found that they were frequently under-utilized, under-maintained, and oppressive in their own right. The point is that rules and incentives that encourage more pleasing neighborhoods need to be firmly grounded in social science research and well-tested before wide-spread implementation. Recreating the mistakes of the past will only cement people’s beliefs that developers can’t be trusted.[3]

At the end of day, we want cities that are both affordable and enjoyable. The way to do this is to build new housing across the city, and to make sure it enhances the urban fabric. Computer Vision can help us see the future before it arrives.

—

[1] Additionally, the word “oppression” in English is most usually associated with unjust political control, not the secondary use of feelings of distress. English speaking subjects might be confused about the word in a study about building heights, which might impact the average responses to those questions.

[2] A previous study “trained” these features to predict perceived neighborhood safety.

[3] Ironically, it may be that the zoning and planning rules that have created people’s negative perceptions about developers, who built out cities according to those rules. They provided parking lots and strip-malls when off street parking was required by law, and they built wide open plazas when incentivized to do so.